Millennium Park, July 10, 2008

Review and photographs by Banning Eyre

In its second year, the Sudan Festival of Music and Dance continues to deliver on its inspirational vision of presenting an artistic image of Sudan that contrasts with the political one. Where the country’s leaders are divided, these artists are unified. On July 10, despite rain and other adverse circumstances—given the sad state of Sudan, how could it be otherwise?—33 artists took the stage at Millennium Park in Chicago and together played music from the north, west, east, center, and south of this tragically divided nation. The music was expansive and varied, however the eight featured singers were all backed by a single orchestra, itself a symbol of the unity that is possible for Sudan. The festival moves on to Detroit’s Concert of Colors on July 19. Click here for more details.

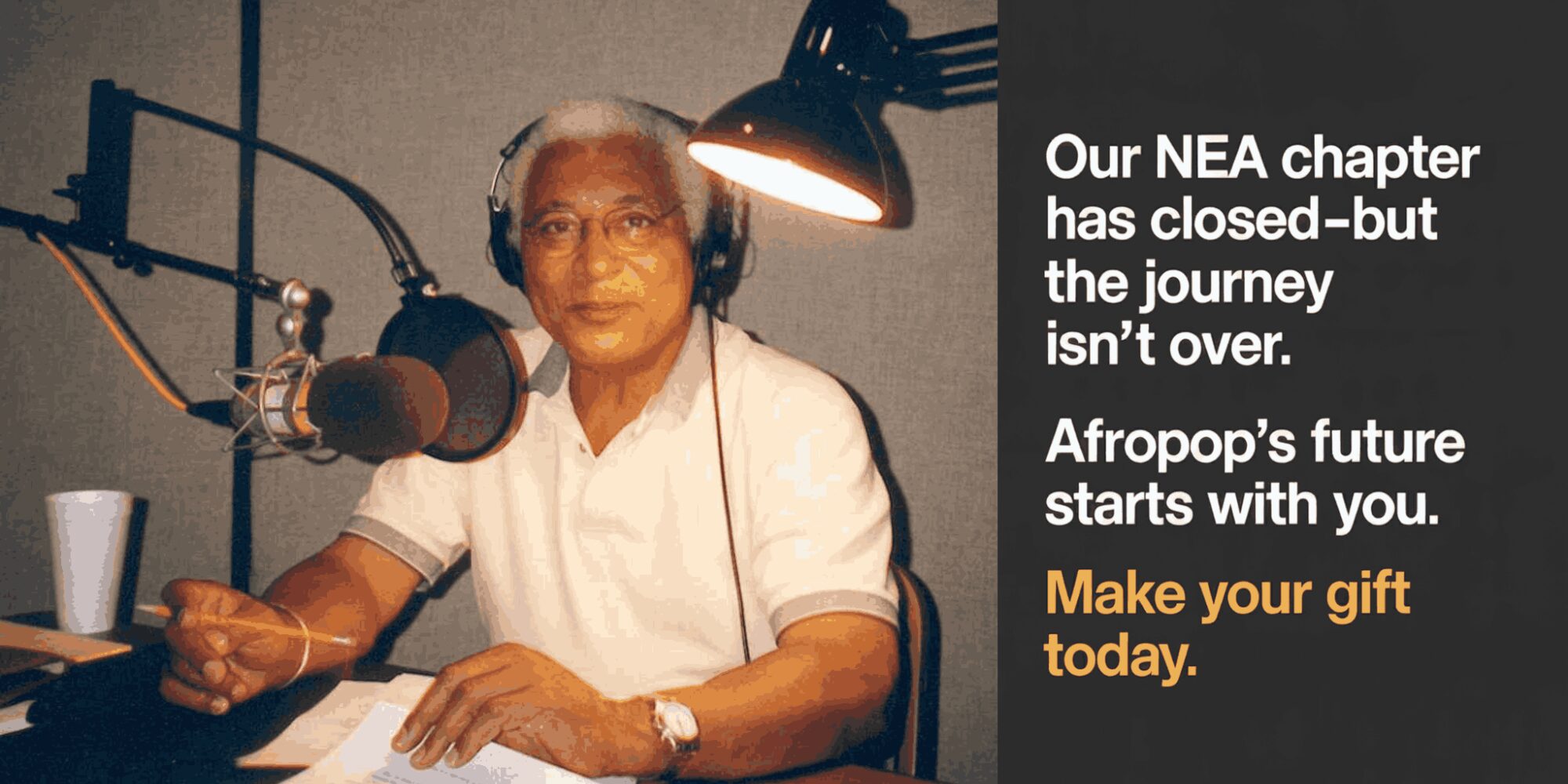

That orchestra was assembled especially for the Chicago and Detroit events under the direction of Yousif El Mosley, affectionately described as the “Quincy Jones of Sudan.” In fact, Sudan’s music scene is so badly divided and dispersed around the world that no figure could really have the breadth, power and influence of a Quincy Jones. And that’s exactly the point. What was so moving about the Chicago performance was the way it dispensed with the tangled and troubled knot of complications that is Sudan and for a brief, satisfying two hours, gave us a taste of the Sudan that could be. As one of the festival’s key organizers, Doctor Mutwakil Mahmoud, put it, “Sudan is the largest country in Africa, almost a million square miles, 300 or 400 ethnic groups, more than 500 dialects, a country where Arabs and Africans have come together. But even after independence, we were never a nation… We are struggling to become a nation.”

That orchestra was assembled especially for the Chicago and Detroit events under the direction of Yousif El Mosley, affectionately described as the “Quincy Jones of Sudan.” In fact, Sudan’s music scene is so badly divided and dispersed around the world that no figure could really have the breadth, power and influence of a Quincy Jones. And that’s exactly the point. What was so moving about the Chicago performance was the way it dispensed with the tangled and troubled knot of complications that is Sudan and for a brief, satisfying two hours, gave us a taste of the Sudan that could be. As one of the festival’s key organizers, Doctor Mutwakil Mahmoud, put it, “Sudan is the largest country in Africa, almost a million square miles, 300 or 400 ethnic groups, more than 500 dialects, a country where Arabs and Africans have come together. But even after independence, we were never a nation… We are struggling to become a nation.”

About those adverse circumstances, it must be noted that three headliners, Abdel Gadir Salim, Abu Araki Albakheit and Rasha, did not appear, apparently due to visa holdups. (With no U.S. embassy in Khartoum, the already complicated process of acquiring a performance visa becomes even more difficult for Sudan-based artists, as everything has to be processed through Cairo.) The good news is that those who did arrive performed fabulously, and they represented enough regional, stylistic, and generational diversity to fulfill the overall mission of the festival.

Finally, with the party in full swing, two of the three sisters of Al Balabil—The Nightingales—took the stage. Al Balabil hale from the ancient, northern kingdom of Nubia, and their music, often backed by the hypnotic rhythms of the tar (frame drum), has the mesmerizing quality of desert music everywhere. This concert had been billed as a long awaited reunion with the third sister. Hadia and Amal both live in the United States, and had their sister Hayat’s visa been processed in time, it would have been the first time for all three to appear on a stage together in many years. No matter. Hadia and Amal had it covered, singing their hearts out, wielding their tars, and whipping the crowd—many old enough to remember Al Balabil from their 1970s heyday when they were thought of as the Supremes of East Africa—into a near frenzy.

As they finished their second song, Hada and Amal moved to the side of the stage where Manute Bol and Chicago Bulls football legend Loual Deng (also from southern Sudan) were standing by, and escorted them to the center. Soon everybody connected with this ambitious festival was on stage, and all the musicians remained to sing together a final song calling for peace in Sudan. Any divisions between southerners and northerners, musicians and organizers, performers and audience, anyone really, seemed to melt away in that moment, and the final image was one of convincing unity. Despite all, these artists achieved their most important goal, demonstrating that Sudanese of all backgrounds can work together and make something beautiful.

Contributed by: Banning Eyre