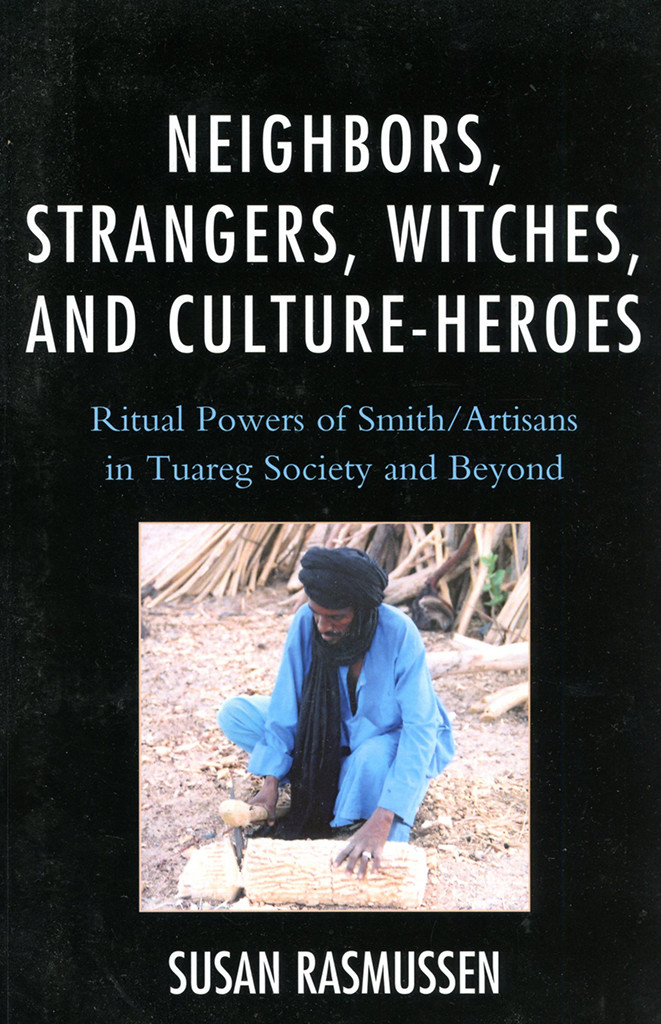

Susan Rasmussen is a professor of anthropology at the University of Houston. She has conducted of some 30 years of field work among rural and urban Tuareg communities in Niger and Mali, and more recently, African immigrants in France. She specializes in anthropology of religion, gender, lifecycle aging, medical and ritual healing, and verbal art performance. Her five books and numerous articles and papers on Tuareg culture include studies of spirit possession, of youth culture in Agadez, Niger, and a study of acting and plays in Kidal, Mali. Banning Eyre spoke with her in preparation for the Hip Deep program, “The Tuareg Predicament in Mali.” Here’s an edited transcript of their conversation.

Note that this transcription uses Susan’s favored spelling for the name of the Tuareg language: Tamajaq. Elsewhere on this site and in the literature, you will find other spellings, such as Tamashek or Tamasheq. This discrepancy, like so many other conundrums, goes with the territory.

Banning Eyre: Let’s start at the beginning. Who are the Tuareg?

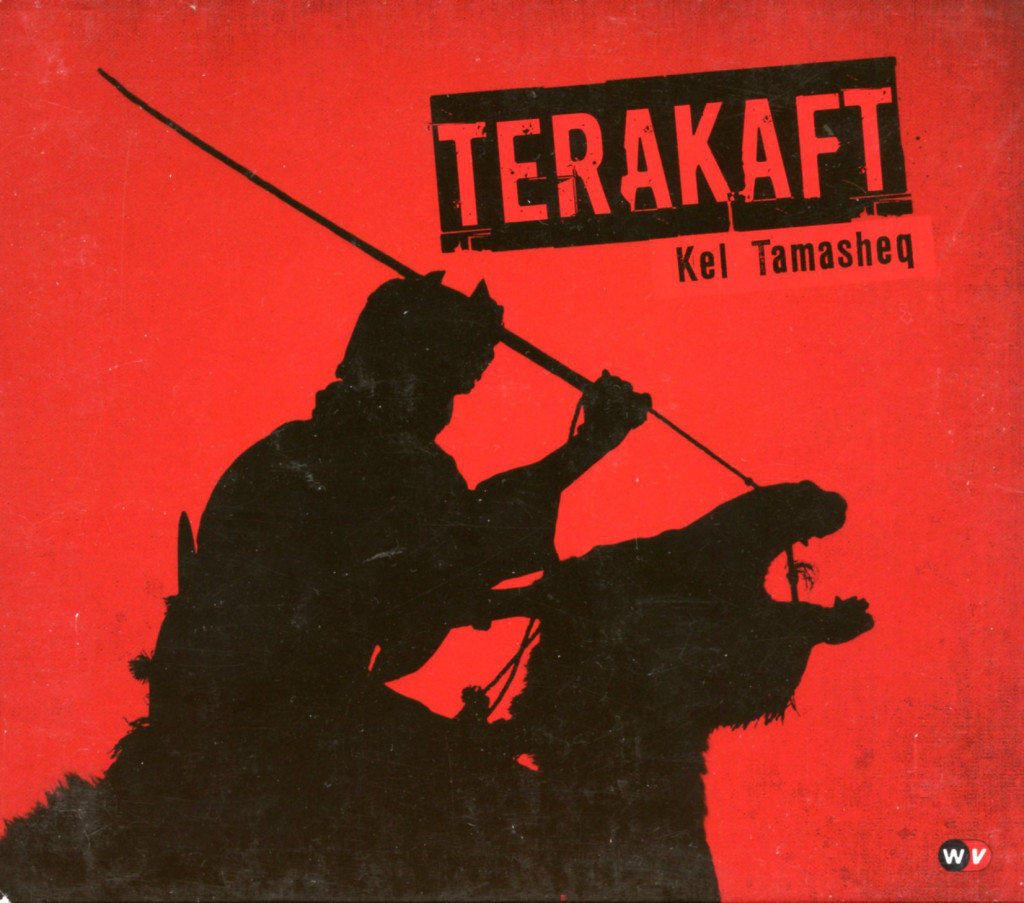

Susan Rasmussen: There’s a mix of myth and history in any account of a people’s origins. Even the term Tuareg is a cover term or a gloss for a number of different groups, though they are closely related. The Tuareg sometimes call themselves Kel Tamajaq , after their language, which is in a family of languages called Berber, or the local term Amazight. The Berber or Amazight people are the original inhabitants of North Africa. The Tuareg themselves fall into large regional confederations, and smaller clans and descent groups. Today, most Tuareg live in the northern areas of Niger and Mali, the southern area of Algeria, Libya and parts of Burkina Faso. Although keep in mind that there have been migrations and dispersions, as well as returns to the central Saharan region for centuries, in response to ecological disasters such as droughts, and also in response to political violence.

Now, I’m not a historian, but I can tell you that the origins of the Tuareg are disputed. Most researchers agree that the Tuareg originated in the central Sahara. It depends on who you read and to whom you speak on the ground when conducting field research. Some can be traced to the Fezzan region in southern Libya. Some of the different groups trace

Susan Rasmussen

Susan Rasmussen

their origins to Morocco or Libya. Others go further back and will trace their ancestries to people in Yemen, largely through trading and the spread of Islam. But keep in mind, there is a diversity within a unity in Tuareg culture. Most Tuareg today identify themselves on the basis of language, Tamajaq. Modern political leaders often appeal to language in an attempt to unify the Tuareg.

Traditionally, the Tuareg are a seminomadic people, until recently, a rural people. Starting in colonial times, and more recently under independent nation-state government policies, or as a result of drought, many have been compelled to settle down on oases. So you do have some sedentarized Tuareg as well. Also, you have itinerant trade, traditionally the caravan trade across the Sahara. Recently the camel caravans are diminishing, giving way to truck trade. But even truck trade has been interrupted by political violence in the region.

I like to think of the Sahara as an ocean with ports. Rather than being very remote, it’s been a vibrant crossroads of trading, of religious scholarship, of culture, of the arts. It is a difficult geographic access, but Tuareg groups have adapted very well to it. The nomads traditionally herded livestock, though this has been disrupted both colonial policies and postcolonial policies.

Tuareg near TImbuktu (Eyre 2003)

Tuareg near TImbuktu (Eyre 2003)

That’s an excellent introduction. And I’m glad you raised this point about how Tuareg is really an umbrella term. But what about this term kel? Sometimes that gets translated as clans, but I’m not sure it’s quite that simple.

Yes. Kel literally translates as “people of.” As I said, there are several major regional confederations of Tuareg. And within these confederations, we have somewhat large descent groups—that is, groups that trace their ancestry to a common founder, often a female founding cultural hero or ancestress, predating conversion to Islam. But also, some will trace to an important Islamic scholar or holy man who came to spread Islam. It varies. But usually the kel signifies one of these subgroups. For example, one of the largest in Mali is the Kel Adagh. That’s the group found to predominate generally around the Kidal and Adrar des Ifoghas region. These are “people of the mountain.” The Kel Aïr tend to predominate in northern Niger, around the Aïr Mountains—including the Bagzane Masif and the town of Agadez. Aïr, I believe, etymologically is a term for caravan trade.

Within these groups, you also see the term kel used to describe various descent groups, smaller units, somewhat like clans. For example, the Kel Ifoghas are very large descent group found within the Kel Adagh federation in northern Mali. Kel can also describe the roles of these groups. Kel Essouk, also prominent in northern Mali, literally means “people of the market.” “Market” is the literal translation of souk, but it also means a crossroad, a place where people come together, ideally in peace. The Kel Essouk have traditionally interpreted the Qur’an for Ifoghas aristocrats. The Kel Essouk try to impose peace, which, of course, has met terrible challenges in recent decades with the turmoil in the Sahara and the Sahel.

The English terms don't do justice to the precise local meeting or role of these groups, but it's an approximation. Particular clan names may or may not be preceded by the term kel. For example, we have the Kel Igurmaden. Prior to disruptions caused by French colonialism and independent nation states, Mali and Niger, these clans were often coordinated in managing subsistence in Sahara desert and desert-fringe Sahelian savanna regions. This required mobility, basically free passage for caravans throughout the region. French colonial powers tried to control the caravan trade by setting up borders. And this of course interfered with delicate ecological, social, and political balances. Now some of these groups have cooperated in trade, have even intermarried. Others have competed over resources such as water, livestock, pasture. As anywhere, the picture is complex. Allegiances and alliances shift.

Interesting. But across all this diversity is the Tamajaq language universally understood?

Yes, it is. To varying degrees, depending on the dialects. It's the way perhaps some English speakers have to listen very closely when they hear, for example, an Australian English dialect, or an old British film. They have to listen carefully. It's not always easy, but yes, indeed, it is the same language despite the different dialects. Now in studies of language and culture, where a dialect ends and a new language starts is a very hazy place. It is gradual. It is not something that you can pinpoint easily. But yes, I can say that most speakers of Tamajaq can manage to understand each other with varying degrees of difficulty.

Which makes it a very logical basis on which to create a sense of unity across diversity.

Yes. The modern leaders are tending to emphasize that. For example they urge their audiences in speeches and songs and poetry: We are all under the same tent. Ehan iyen. Which means one tent. Ehan is tent, iyen is the number one.

Tuareg group dancing takamba, seated (Eyre 2016)

Tuareg group dancing takamba, seated (Eyre 2016)

I want to ask about the status of women in Tuareg society. I understand that gender roles distinguish Tuareg communities from some of those around them.

Yes, indeed. One can say, while remaining wary of overgeneralization, that many Tuareg women enjoy high social prestige and economic independence. In most groups, particularly the more nomadic groups, the major source of women's wealth was in livestock. Now, because of a series of droughts and intermittent wars, livestock herds have been much reduced. Therefore some women have become less wealthy. Certain NGO agencies and other programs in northern Mali and Niger are training Tuareg women in other professions such as tailoring, oasis gardening and other alternatives. This is something new, very novel and different from the tradition in which women did not plant.

But in Tuareg society, women still enjoy a high degree of free sociability, even in public. Most women can visit and travel freely—except perhaps those who are married to more conservative Arab men or devout Muslims who interpret the Qur’an as requiring seclusion of women. And keep in mind, there is always cultural interpretation involved. Not all Muslims even agree on that. But most Tuareg women are not secluded. They can represent themselves legally. They have a right to initiate divorce. They also, as I said, inherit, own and manage their own property, which has traditionally included livestock, date palms. A few women own houses. Fewer women own houses than men, however. But central here, especially in the rural and nomadic groups is the nuptial tent. The woman in seminomadic or nomadic camps owns her tent. It is brought to her marriage as a dowry. And she can eject the husband from it upon a quarrel or upon divorce.

The situation becomes complicated in some areas of seminomadic agro-pastoralism because men are building a lot of houses that they tend to own. And you will have situations sometimes with a house and a tent in the same compound, and upon quarreling or divorce, there arises a conflict about who stays and who leaves.

In general, most Tuareg men will still tell you they respect women. Women should be treated equally. As a a few told me in French their women are “like princesses,” and they have to be respected. Now of course as anywhere, as in any society, what people say and what is ideal are not followed by everybody perfectly. Wife beating is considered very shameful. In fact, ideally, a man is not to be angry with a woman. If he gets angry with a woman, she can lodge a complaint and he can be summoned, so to speak, called to the carpet by a group of men who can impose a fine on him. I have seen several cases of this happening.

One more point concerning inheritance. Almost all Tuareg adhere to Islam, and officially, there is Qur’anic inheritance, which gives two-thirds of property to the male heir and only one third to the female heir. But many Tuareg practice additional inheritance forms that compensate women for that disparity. In other words, women have special compensatory means of inheriting property, for example living milk herds in the case of livestock. These are forms of property that are bequeathed to women. There also pre-inheritance gifts. So there are alternative forms of inheritance that benefit women as well as men.

Fadimata Walet Oumar (Disco) of Tartit (Eyre 2016)

Fadimata Walet Oumar (Disco) of Tartit (Eyre 2016)

Interesting. Knowing Tuareg musicians, for example in the band Tartit, which has very powerful women at its center, I have always sensed that they have a different way about them. In Mali, women generally carry themselves with a great sense of confidence and power that you don't necessarily feel in other parts of Africa.

Yes. Sometimes in the towns, there is multiethnic influence, not to mention fear of the more militant Islamist reformist revivalists. Sometimes this does produce modifications in gender roles. But gender arrangements tend to be more flexible in Tuareg society than in some of their neighbors’ communities.

We will come to the question of Islam in a moment. But first, we sometimes hear and read about “white Tuareg" and "black Tuareg." People in Mali talk about the Bella people as slaves or former slaves of the Tuareg. I'd like you to untangle this, and talk about how this relationship plays out in modern times.

Yes, of course. There has been a great deal of misunderstanding in much, though not all, of the popular media, about the hierarchical nature of Tuareg society. It is traditionally a ranked, hierarchical, stratified society. That is, you have a cluster of occupational groups whose occupational specialties were traditionally inherited based on descent. But let’s bracket that and talk about the Bella, or Buzu as they're called in Niger. First of all, there is a great deal of distortion in some popular media that's highly unfortunate, and in my opinion and that of many other scholars on Tuareg society, dangerous. Popular media sometimes imposes Western pseudo-racial concepts, Western folk beliefs concerning so-called race, on the Tuareg. In fact, one finds quite a variety of physical appearances, including complexion tones, among the different social categories. For example, among persons of aristocratic social backgrounds in the precolonial system, one finds persons an American might think of as black. Conversely, among some more subordinate persons, one might find a different appearance that might be lighter. So we have to avoid projecting our own European and American folk beliefs about so-called race onto other societies.

In Mali and Niger, slaves first began to be freed around the turn of the 20th century, and were completely freed legally around midcentury, at the time of independence. Now as anywhere, sometimes there is a lag between public legal policies and actual social or economic practices. Witness the way in the United States, some racism is unfortunately still with us despite the civil rights movement and the liberation of slaves in our own country.

Tuareg at 2003 Festival in the Desert (Eyre 2003)

Tuareg at 2003 Festival in the Desert (Eyre 2003)

Today, the situation of the Bella—former servile people in Tuareg society—is highly variable. In towns, some Bella are well represented in some of the jobs in the new infrastructures. And there is a reason for this. Initially, when the French introduced nomadic boarding schools—and later some independent nation-state governments continued this—they established certain quotas for school registration. And at first, aristocratic Tuareg and Tuareg in pre-colonial traditional leadership positions tended to shun the schools because they viewed them as a threat to their culture. They suspected that the schools were magnets for controlling the nomads by taking censuses, levying taxes… So they often sent the children of their subordinates to school instead. As a result, many persons of more servile social backgrounds became more exposed to secular modern education.

In the countryside, again, there is variation for the Bella in Mali and the Buzu in Niger. By the way the Tamajaq term was iklan, “those who are owned.” They are no longer owned. Today, they must be paid for their work. Now some of them in the countryside do tend to still do more menial jobs, but they are paid for them. I personally am unaware of any enforced labor without pay in the communities where I have worked, in either rural or urban communities. Also, one should note that it was not only the Tuareg who took slaves, and not all Tuareg had slaves Sometimes popular literature and press give that impression, but it’s simply not true. Some Hausa in Niger had slaves, as did some Songhai and some Bambara. These were societies were stratified, ranked societies, and there was a mutual dependence between the different social categories.

In the past, there was very little intermarriage between the social categories, but this has changed completely, particularly in the towns. One reason is that many Tuareg men have become impoverished. Some families try to marry their daughters to more prosperous suitors to escape poverty. Some of the more prosperous suitors come from either a different social background, or even a different regional or ethnic background. I have encountered many multilinguistic families, particularly in the towns.

Tumast culture center in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

Tumast culture center in Bamako (Eyre 2016)

One quick clarification on the Bella. The Bella are also Tuareg, aren't they? They also speak Tamajaq?

Yes. They speak Tamajaq. They dress much like Tuareg these days. You will read in some of the historical and ethnographic literature about what we call sumptuary laws, laws similar to those existing in medieval Europe about who could wear what kind of dress. For example, only nobles, the aristocrats, were permitted to wear silver jewelry or carry long saber swords. They monopolized weapons and livestock. But that is long past. When you read about Tuareg stratification, you have to be very careful; you have to think about when it was written. A hundred years ago, there was very little intermarriage, and Bella didn't wear silver.

There are remnants of the past relationships. On an oasis about thirty years ago, for example a group of descendants of slaves might come in and help with mat and ten repair. But in exchange, they are now paid or given various things. It is not forced labor, or defined as slavery. It's a kind of trade. It's almost like a sewing bee or a barn-raising party in the United States.

So the past echoes in some patterns of the present.

Yes. But keep in mind, that these Sahelian and Saharan societies were traditionally ranked and occupationally specialized. There were the smith artisans. In some societies there were griots, musicians. There were Qur’anic scholars. It was a very complex society, and all of these groups were ultimately dependent upon each other.

Tuareg woman at the Festival in the Desert (Eyre 2003)

Tuareg woman at the Festival in the Desert (Eyre 2003)

Let's turn to the question of Islam and conversion. When it happened, how it happened, and how it was particularly problematic for the glory given the nature of their culture.

That’s an interesting question. It's vast. In order to address it, it's good to refer back first to the larger Berber or Amazight groups who originated in North Africa, and the arrival of the Arabs. Most of these original peoples, including the Tuareg, resisted Islam initially. They converted at various times between the eighth and the 12th centuries of our current era (CE). Amazight people tended to cluster in the mountainous masses found throughout the Sahara—the Moroccan Atlas Mountains, the Ahagar or Hogar Mountains in Algeria, Adagh-n-Ifoghas as in Mali, the Aïr massif in Niger. They were difficult to access, not isolated, but difficult to remote and elevated for defense in times of armed conflicts.. So initially many resisted, in part because their social institutions were very different from Arab institutions.

We have to distinguish between what is Islamic and Koranic and what is culturally Arabic, and that is a complicated question. Arabic cultural patrilineal institutions, that is, inheritance and descent legally calculated through males on the father's side, were imported. Now Islam, like other religions, is also subject to interpretation, and different Muslims have interpreted this and other injunctions differently. So we have to think in terms of Arabic cultural and legal influence along with the importation of Islam into continental Africa. In addition, French colonial legal institutions tended to import patriliny into their colonized areas.

Now, patriliny–that is, calculating one's descent and passing property through men—definitely was in some ways incompatible with the local Tuareg system of matrilineal ancestors. Matriliny involves tracing your descent to a female ancestral culture hero, and passing property through women, on the mother’s side. Men are included in matrilineal systems, as women are included in patrilineal systems. I don't want to get too jargony here. But the Tuareg and some other Amazigh people initially experienced a lot of conflict with this. Matriliny isn't matriarchy. It doesn't mean that women rule. In Tuareg society, men have tended to be the official leaders, the chiefs, the heads of the confederations, and so on. But matriliny gives women a prominent place in mythical history, and provides forms of inheritance more favorable to women. So there was a clash over culture, not just religion.

To make a long story short, Tuareg were unevenly converted, and over a number of centuries. Some groups of Tuareg are more devoutly Islamic than others. For example, in my own work, I did quite a bit of research on medical ritual healing, using herbal medicine—predominantly women's work. One finds not solely conflict, but also a very compatible and flexible combination of Islamic and pre-Islamic, or popular Islamic beliefs and practices. In fact, many Tuareg herbal medicine women insisted to me that Islamic scholars and herbal medicine women are like husband and wife. They are complementary. They respect each other. Islamic scholars sometimes cure patients with verses from the Qur’an. There are certain kinds of illnesses that are amenable to that, usually nonorganic, or what we might call mental illnesses. Well, sometimes these Qur’anic verses may not cure a patient. So in that case they refer the patient to the herbal medicine women, who tend to cure with plants, roots, leaves, barks. Some do more complicated divination in dreams—a sort of psycho-social counseling.

To make a long story short, Tuareg were unevenly converted, and over a number of centuries. Some groups of Tuareg are more devoutly Islamic than others. For example, in my own work, I did quite a bit of research on medical ritual healing, using herbal medicine—predominantly women's work. One finds not solely conflict, but also a very compatible and flexible combination of Islamic and pre-Islamic, or popular Islamic beliefs and practices. In fact, many Tuareg herbal medicine women insisted to me that Islamic scholars and herbal medicine women are like husband and wife. They are complementary. They respect each other. Islamic scholars sometimes cure patients with verses from the Qur’an. There are certain kinds of illnesses that are amenable to that, usually nonorganic, or what we might call mental illnesses. Well, sometimes these Qur’anic verses may not cure a patient. So in that case they refer the patient to the herbal medicine women, who tend to cure with plants, roots, leaves, barks. Some do more complicated divination in dreams—a sort of psycho-social counseling.

They may also refer a patient to a practitioner who uses drummers and musicians in a spirit possession exorcism ceremony. In this case, people are defined as being invaded by alien spirits, and music is a kind of a group therapy with songs and drumming and general support from a small, usually rather intimate audience of friends, neighbors and relatives. This is considered non-Islamic, and many Islamic scholars will faintly disapprove of it. Often they don't attend. But they don't usually forbid it, except in the case of the more recent militant Islamic reformist revivalists. But keep in mind, most Tuareg are very cool towards these new reformist Islamist movements, certainly the more militant ones. Because not all the reformist Islamist movements are violent. Some of them are, but others aren't.

O.K., let's bring this up to the present. With all this as background, give us a clear view of what happened in Mali in 2012.

I will try to be concise. It's complicated. One reason those more militant groups were able to come into those northern regions was the withdrawal of services. Starting in the late 1980s, restructuring by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund compelled African governments to privatize and withdraw certain services. This impoverished many people, and consequently, some of the Islamist piety organizations, not all of whom are violent–I want to emphasize that–moved in to fill that gap building clinics and schools in northern Mali and Niger.

That's crucial. But when the actual 2012 rebellion came, the original idea was to declare a separate political territory in the north, Azawad.

Well, I'm not really into the politics that much. But I think at that time, the African Union never recognized Azawad. Prior to 2012, the goal had been semi-autonomy. For example, the Kidal region was declared the eighth region of Mali. It was no longer to be under military rule as it previously had been. There had been atrocities committed in the Kidal region going back to 1963, the time of the first nomadic uprising in Mali. It was disputed how the food was being distributed. It was argued, for example, that the nomads had been required to come in and settle down in order to receive food. The point is, there had been tensions.

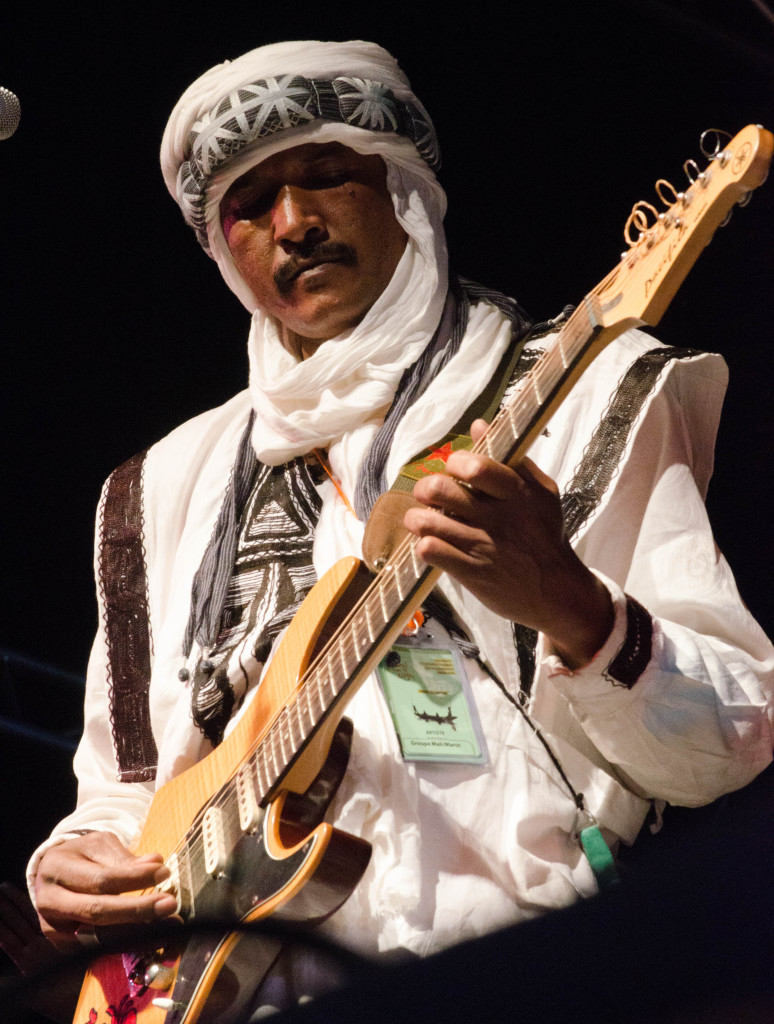

Most Tuareg leaders have not necessarily favored complete independence, just some level of cultural autonomy, more resources built in the north, schools, clinics and hospitals, more Tuareg admitted into the national army. Also more Tuareg in jobs in the modern infrastructures of the towns. There were certain promises made to returning exiles who had emigrated away from those countries, who came home and they found themselves unemployed. I'm sure you've read that this situation has to do with the early origins of that popular guitar music, ishumar.

Tinariwen, Brooklyn, (Eyre 2012)

Tinariwen, Brooklyn, (Eyre 2012)

Right. The name actually comes from the French word chomeur, “unemployed.”

Anyway, the so-called rebels who established independent Azawad did not find support, even though they called on all Azawadis to come home. They didn't use the term Tuareg; they used Azawadi. So this wasn't some kind of racist apartheid state. They wanted all Azawadis to come home. They promised to practice a democratic system. They called on all other armed groups to leave the area. Of course they didn't obey, as we know. And Islamist militant groups were able to easily move in to that kind of power vacuum. The militants came in at first professing to help the Tuareg separatists, but later they took over.

When you say they call themselves Azawadis, did that include the Songhai, the Bozo, the Dogon, the Fulani?

Yes. I mean, many of them did not intend it to be strictly one ethnic group. As I say, I am not an expert on the political situation. But I know that initially there were Tuareg leaders who wanted a degree of cultural autonomy, also more representation in the jobs in the state structures, and more resources in the north. So the declaration of Azawad was connected with hopes to develop the region. But I can't really speak for Tuareg political viewpoints. You need more context on the ground from local viewpoints, and I tend to shun partisan politics when I do my research as much as possible.

Understandably. I think the politics of this situation really turned around on Tuareg musicians too. Some ishumar bands had been singing for rebellion, but once the jihadists took the upper hand, they actually tried to ban music altogether.

Ishumar guitar music originated in the Tuareg rebels during the '80s and '90s, with the exiles and migrants. Originally it was protest music. But I've collected much of this myself in the field, because one of my interest is in verbal art performances. And many of the verses of songs later advocated peace. So they evolve somewhat. At first they were political protest music, and then later, they promoted peace and reconciliation.

Well that’s something we will look into. But I have a question about the music of the ishumar guitar bands. Is it a continuation of pre-existing traditional music? Or is it something entirely new?

I'm glad you asked this question. First of all, music, songs and poetry are of absolute central importance in Tuareg communities. That’s long-standing. Now traditionally, specific musical instruments and genres tended to be associated with the different social categories, you know, in the old ranked system. But that's no longer true. In fact one goal of the original composers and performers of ishumar guitar music was to get around this. One reason the guitar appealed to them was because it was an instrument anybody could play. It was from outside Tuareg society, and they used it as a symbol of equality in order to draw the diverse people in Tuareg communities together. In other words, the guitar was not associated in their viewpoint with the old, precolonial differences in status.

Ahmed Ag Kaedi of Amanar (Eyre 2016)

Ahmed Ag Kaedi of Amanar (Eyre 2016)

That certainly makes sense.

This music is extremely central now. Many of the performers are trying to use music and performance as a way of healing themselves from their experiences during the recent political violence and ecological disasters, such as the drought, but also to bring other people together. Whether it's a religious ceremony, or a musical festival, the idea is inclusive. Artists are supposed to bring people together.

Now anybody in Tuareg society can become respected and renowned through composition, performing, music, or singing, or poetry—regardless of their social background. Even in precolonial Tuareg society, a person of subordinate status could be respected if they were a talented poet, for example. So it's logical that music would become a way of channeling efforts to reconcile people and bring people together.

There's another important point about much of the poetry and singing. In traditional Tuareg culture, this quality of reserve, takarakit, is widely valued. Many sentiments, such as love and anger, are not supposed to be directly expressed. In other words, rather than telling these things directly in conversations, you're supposed to convey them indirectly. One way of doing this is through music, song and poetry, so that's another important role of performance. For example, in my own research on spirit possession, and songs that they sing at this musical group therapy rite, often the verses will refer to a secret love, but they won't mention this directly, or name the people involved. Instead, they might praise somebody's camel. Or, if you dislike somebody but you are not allowed to be aggressive towards him directly, you might name your dog after them.

That's interesting. So this word is takarakit, and it translates as “reserve.”

Approximately. Reserve, respect. It's practiced more between some people than others. For example, a newly married bridegroom, or even a longer-married husband, is supposed to practice reserve towards his parents-in-law a lot. But nevertheless, in general, there is a tendency, and I call it a tendency because not everybody observes it, it's supposed to be a polite way of behaving. And as anywhere, as with anything like that, not everybody practices it, but it's the idea.

I remember struggling to get translations of song lyrics when I first met Tinariwen back in 2002. Maybe that’s part of the reason.

Well, there are layers of meaning. Another important concept you might find interesting is tangalt. That's the Niger Tamajaq term. But this aesthetic concept is important in Mali too. This approximately translates as "symbol." Metaphor, shadowy speech. There's a great deal of value placed upon that, particularly in the poetry and song lyrics.

I'd like to ask you one question about griots in Tuareg culture. I am familiar with Mande griots. I lived with a family and studied guitar with a great griot guitarist. Are Tuareg griots similar?

It depends on where you are. In the groups I work with, griots tend to be from other ethnic groups. The Tuareg often use the services of a griot, but in the places where I worked, they really didn't have their own griots. There are many griots throughout the entire Sahel—Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Senegal. But in the Tuareg communities where I worked, they tend to use the services of griots from a neighboring group, not necessarily related to the Tuareg families. They don't marry into them; they tend to marry among themselves. Now in some other Tuareg groups, for example in the rural Aïr Mountains, I found that smith artisans actually perform like griots. They will sing praise songs of aristocratic families at weddings and other rites of passage, such as babies’ name-days. Another researcher confirmed it. Dominic Casajus, a French researcher who also worked in the Aïr Mountains.

Still, the performance of some types of verbal art, such as praise-songs, are generally associated with inherited social categories such as griots and smith artisans. That's very widespread in all Tuareg communities. But the precise relationship of the griots to the Tuareg, I confess to you, I am not certain about in all groups. The ones I know best tend to use the service of griots from the neighbors.

Tuareg griots playing tehardent lutes (Eyre 2003)

Tuareg griots playing tehardent lutes (Eyre 2003)

Interesting. And when you say neighbors, do you mean other Tuareg?

Not necessarily. It might be a Songhai griot or an itinerant Bambara griot. When I was in Kidal, Mali, I conducted this study of acting in plays in urban Tuareg society there. I just finished the book manuscript. It hasn't been published yet. The actors kept telling me very emphatically that they were not griots. But there is some overlap with the specialty of griots.

We will leave that to further investigation. Maybe they feel that mediators such as griots who come from outside would be more objective in their verbal art.

Right. It's a similar position to the Tuareg smith artisans. You are a go-between. You don't usually marry in to that group, and therefore you can mediate between them. You don't have a stake in the game personally.

This is great, Susan. Thanks so much for all this.