The Lusophone Atlantic is, in so many ways, a world of its own. Forced together by Portuguese imperialism, the nations of Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tome and Principe, and Mozambique were, until the mid-'70s, kept apart from the broader currents of African culture, locked into a colonial network that both stifled and encouraged the creation of a uniquely shared identity. Not only did the Portuguese remain a direct colonial power longer (by over a decade) than any other European nation, but they also started far earlier. Long before Christopher Columbus made landfall on the island of Hispaniola, Portuguese traders were moving up and down the African coast, trading, fighting, dying and—in the process—creating the world’s first creole society.

All of this is important to keep in mind when thinking about the remarkable musical culture of Cape Verde, a small chain of Atlantic islands a few hundred miles west of the coast of Senegal. Ground zero for the brutal cultural processes that would go on to birth so much of the New World, Cape Verde has been a zone of mixture and fusion for over five centuries, with musical and cultural connections that run throughout the broad sweep of the Atlantic ocean. And these connections don’t only date back to the distant past. Rocked by repeated droughts in the years since independence, the Cape Verdean diaspora is legendary, boasting communities everywhere from New Bedford, Mass. to Rotterdam, Lisbon or Paris. To understand Cape Verdean music then, it’s not only necessary to focus on the physical boundaries of the island nation, but on the far more diffuse enclaves of diaspora which dot Europe and the Americas.

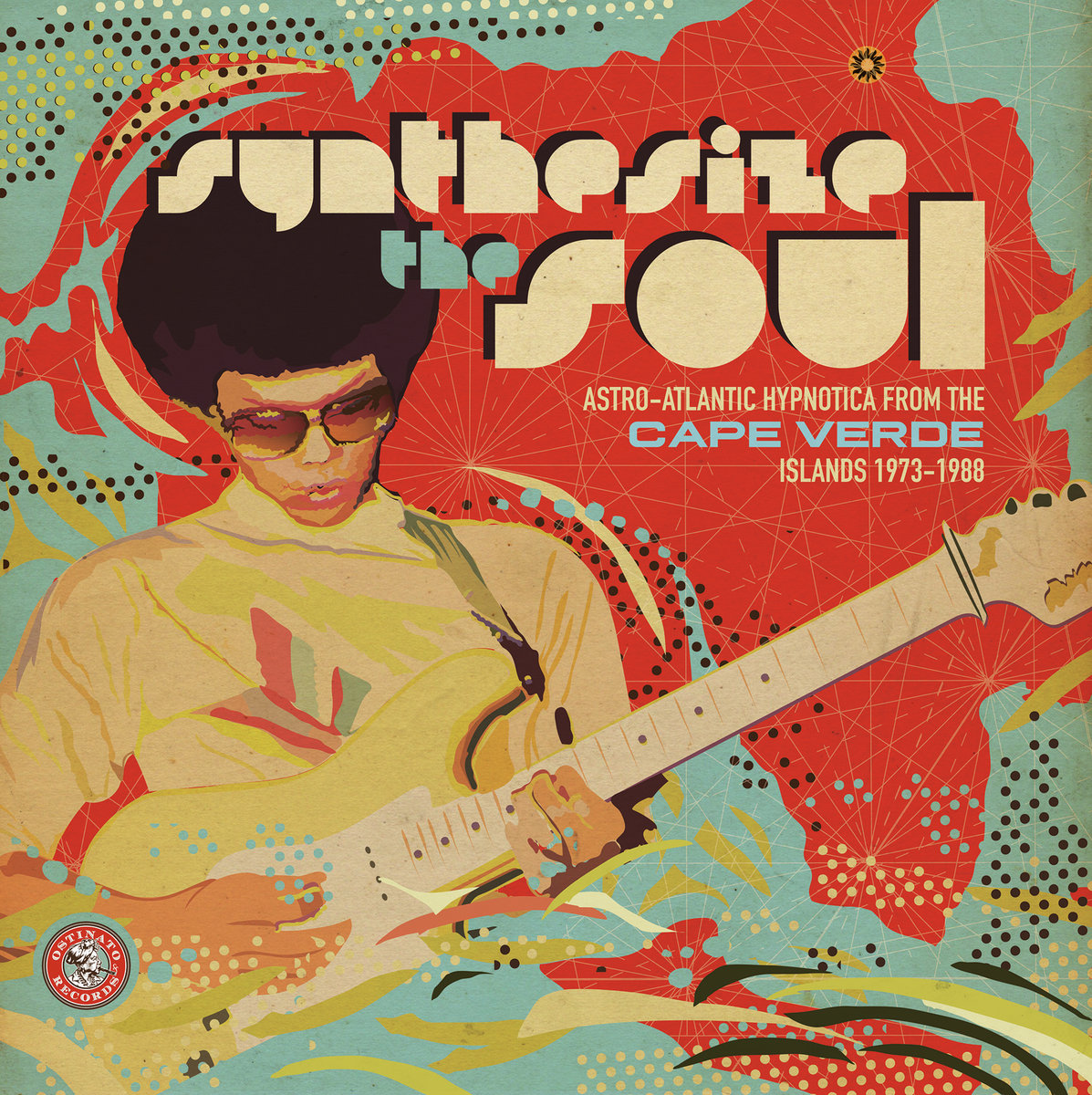

You can hear all of this history on Synthesize the Soul, a fantastic new compilation of Cape Verdean music released by Ostinato Records. Pulling from a universe of rare vinyl previously available only to hard-core collectors, the disc depicts a nation fully integrated into the synthetic world of '80s pop, eagerly developing its own neon-hued version of modernity. Primarily created by bands working in a network of cities across Africa and Europe, the result is a remarkable diasporic dance sound, both unmistakably Cape Verdean and tightly attuned to the cosmopolitan genres of disco, funk, zouk, salsa, and r&b that dominated international dance floors during the '70s and '80s. Because of its close relationship with these more familiar music styles, listening to Synthesize the Soul also provides a kind of shadow history of a far more traditional pop story, revealing an entire universe of scratching guitars, walking bass lines, and synthesizer riffs that would (at least in America) soon be effaced by the rise of hip-hop.

A perfect example of this is served up by “Dança Dança T'Manche,” by Val Xalino. Opening with a mechanical beat that wouldn't sound out of place in the most leaden disco track, the song slides into an elegantly syncopated two-chord pattern, layering swooping synth melodies and chirping keyboards around a gently authoritative vocal and funk-heavy bass line. The effect is like something off "Combat Rock" by the Clash, if Joe Strummer and Mick Jones had traded lover's rock for Antillean zouk. Combining Caribbean and American styles with European classical runs, and an approach to melody and layering straight from the home islands, the result exemplifies the musical wonders that litter this compilation.

As the word “synthesize” in the title indicates, the music featured on this compilation also tells a story about technology. After decades of repression, a generation of Cape Verdean musicians looked towards the synthesizer as a primary indicator of modernity—a way to move away from the colonial past and into the future. At the same time, the use of technology in this music is also about the actual evolution of recording. As musicians spread out through the diaspora, they gained access to synthesizers, studios, and drum machines unavailable back home. As a result, Cape Verdean music grew radically de-centered, as the hottest tracks, the ones best able to bridge the gap between back-country African roots and international pop gloss, increasingly came from outside, created by immigrant musicians working on the edges of more established pop scenes. This remarkable situation helped to inject the music with a radical openness to new sounds and styles—it was always necessarily in conversation with the wider world.

The imaginative leaps created by this fusion are all over “Nós Criola,” by Nhú De Ped'Bia, the album’s first track. It opens like an alien landing, as space-age synths whirl above rhythm guitar chops, before massed keyboards and horns hit and splinter into the kind of dense, melancholy groove that defines so much of Cape Verdean music. Avoiding anything like the sharp edges of American funk or disco’s four-on-the-floor thump, the track brings the groove to a simmer, and then keeps it there, marinating in r&b-style keyboard soloing and low-end bass riffs. That same vibe holds on Pedrinho's “Nanda,” the album’s next track. Dueling guitars and synth wind over a pleading lead vocal while the rhythm section holds the tension with glorious restraint, the whole ensemble pushing at their limits as they slowly build to an explosive solo break.

Quite apart from all of the boundary crossing, many of the most exciting cuts are those that stay closest to the local styles of funana and batuku. For those who have never danced to either, some of what’s here will be a revelatory introduction to a pair of musical styles that have received far too little attention. Whether featuring synthesizers or more traditional accordion, nothing can disguise the frantic groove of tracks like “Chuma Lopes” by Elisio Gomes and Joachim Varela, or “Chema” by Pedrinho—this is dance music par excellence, insistent, enticing, and hypnotically repetitive. While the combination of groove and synthesizer may not quite bear out the liner notes' argument that these tracks offer an “alternative history of electronic music,” there is certainly an aesthetic connection that can be drawn between the rhythmic glory of house or techno and the deep grooves of funana, even absent a direct historical one.

The similarities heard in these tracks—and all over this album, really—offer a remarkable position from which to rethink so many of the broader currents of popular music. From the perspective of tracks like “Chema” or “Dança Dança T'Manche,” it’s possible to hear disco or funk or techno for what they truly are—Afro-diasporic outcroppings, part of a far larger, and far deeper, conversation. These tracks don’t sound like a pale local copies of their better-known cousins, but like another chapter in the story, a reminder that pop is always deeper and stranger than we know.

Sam Backer is a producer for Afropop Worldwide and a PhD candidate in History at Johns Hopkins University. He has worked extensively on the Lusophone Atlantic-- check out his shows "A Brief Guide to the Afro-Lusophone Atlantic: Dancing Toward The Future" and "A Beginner’s Guide to Lusophone Atlantic Music."