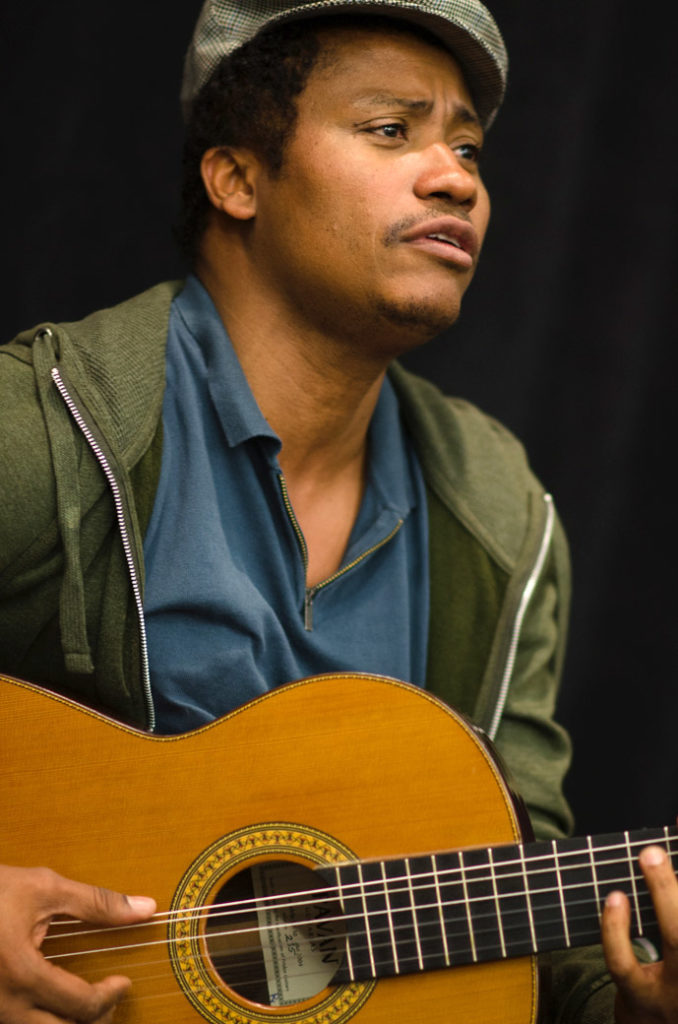

Tcheka (born Manuel Lopes Andrade) is a Cape Verdean original, a singer/songwriter/guitarist who has mastered the traditional idioms of his musically rich island nation, and channeled them into an expressive style all his own. He has recorded and toured with his five-piece band, and collaborated with artists from Lenine of Brazil to Derek Gripper of South Africa—both singular guitar stylists in their own right. Tcheka’s fifth album Boka Kafé breaks new ground with a live, unaccompanied solo set of performances. His near-orchestral approach to guitar is nothing short of remarkable, bursting with rhythm, robust bass lines, delicately nuanced melodies, all creating a stage for his dry, slightly raspy, deeply soulful voice. Tcheka showcased his solo virtuosity at Lincoln Center in two shows in July 2017. After the first, an intimate set at Lincoln Center Education, he sat down with Banning Eyre for a conversation. Tcheka’s manager Johnny Fernandes translated between Banning’s English and Tcheka’s Portuguese.

Banning Eyre: Tcheka, let’s start at the beginning. Tell me how you became a musician in the first place.

Tcheka: I started playing at home. I was actually forced to play. My father was a violinist. Basically the family used to play at my dad's concerts to raise money. So thanks to my father, I started playing, but then I wanted to look for my own thing, my own way of playing. I didn't really have anyone else to play with in terms of what I was looking for. So I just started doing it on my own.

What kind of music was your dad playing? And when you say he forced you, was he forcing you to play guitar?

We played traditional Cape Verdean music. Morna, coladeira, just like Cesaria Evora’s music. At first I played cavaquinho and traditional viola, and Portuguese guitar that they adapted in Cape Verde. The particular guitar is not actually used to now. It's lost its place. It was a nine- or 10-string instrument that you played to accompany the violin.

Is that like the Portuguese guitar they use in fado?

No it's not that Portuguese guitar. It's similar. They use it more for festivities.

So you learned a lot of traditional songs right at the start. But the way you play now is very distinctive. It's not really like anybody else I’ve heard in Cape Verdean music. How did that happen? How did you develop your own style?

At one point, I was on my own. My brothers had moved. I was still there, and I was looking for something. I needed bass. I needed percussion. So I started looking for ways to do that on my own, to create those sounds myself. I was saying, “You need that bass. You need that instrumentation.” So I just created this way to accompany myself—to create my own band essentially.

Tcheka (Eyre, 2017)

That's interesting. I was thinking that as I was watching you play. You have a very orchestral way of playing. You create the rhythm section with the strong bass, and there’s lots of tapping and rhythmic elements. You're creating layers of sound and you're doing all that with your fingers—no picks.

It is difficult when you are one musician on stage and you have to play a concert that's an hour, or an hour and a half. You have to play in a way to create different dynamics so that the audience doesn't get tired of listening to the same thing. So that's what I'm looking for. How do I create that? It's important to create an ambience for the audience.

The guitar is such a flexible instrument. There are so many different ways you can play it. The way you are working all the rhythms, those little rhythms to put in between your melodies. It reminds me a little of D’Gary from Madagascar. Have you listened to him?

No. No.

You should. He is another guy who plays like no one else. So let's talk about the guitar, and that quality that you have where you can create so many different approaches. If you play the trumpet, there’s pretty much one way to do it. It doesn't have the same range of language that you have on guitar.

That’s true. An instrument like a saxophone or piano has its sound. But guitar lets you to create so many sounds, but it also forces you to play every day. I noticed if I don't play for two days, I lose that touch. I have to be constantly doing that and looking for those sounds.

You play two guitars, nylon and steel string. Do they have different personalities for you?

Basically, on the nylon, what I am trying to do is to convey all those little nuances that I haven't been able to find with a pickup. I use a microphone, to keep it sounding as natural as possible. I have been doing research in trying various things to try to get the sound that I want, as natural as possible. The guitar for me is an accompaniment to my voice. When I started out, I didn't know about nylon strings. It was steel. My father would beat me if I broke a string, because we had no strings. Basically we would just find wire to serve as strings.

It is one thing being very good technically on guitar. For me, it's more about trying to get those little details out of different guitars, to get the sound that you want. Use this guitar for this, to get those little sounds that you might not get even if you have a lot of experience and a lot of theory. I am somebody who wants a project on his own terms with the guitar, I have to have this close relationship with the instrument, and just keep on working.

Let's talk biography for a moment. When were you born?

20 July 1972 in Cape Verde, Santiago.

O.K., so the time when you were playing with your father would have been the 1980s.

Yes, '80s. Until I was 19.

What about the point when you first performed on your own.? Tell me about the beginning of Tcheka as a solo artist.

Well, I worked as a cameraman for Cape Verdean television. And I used to hang out and play with some my friends. Some of them said, “Hey, you're doing something interesting.” That's how I started. I recorded my first album starting in 2001.

I see this list of albums in the program notes from the show today. Talk to me about these albums. What were you trying to accomplish with each of them?

I did not enjoy the studio at all at first. The first time [Argui, 2003], I had no idea what to do with anything, the microphones, any of it. And then the pressure from the producer. And you think, "O.K., this person has more experience." And so you let them do it, and then I kind of lost control over my own art. But it was a phase. If I had known then what I know now, it would've come out differently.

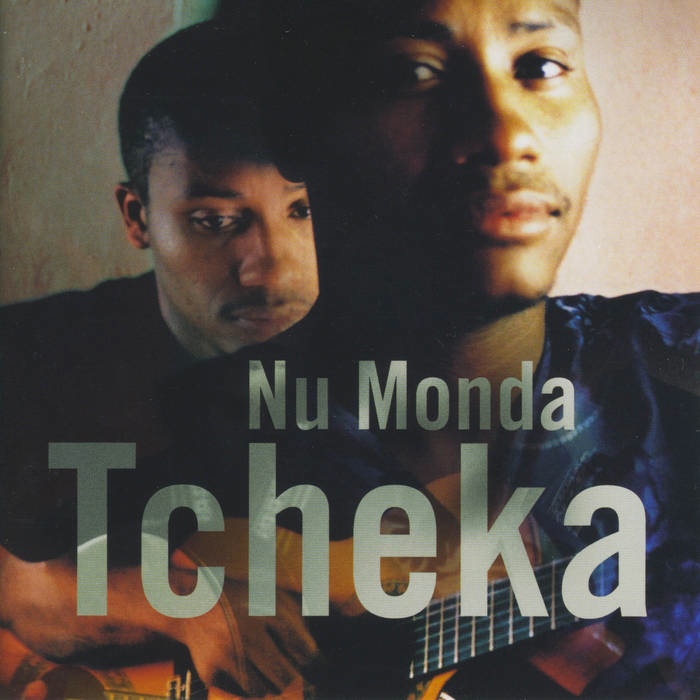

So that was the first time. By the time you got to Nu Monda, in 2005 was it better?

Yes, but then with Lonji [2007] it was kind of the same thing again. It was produced in the Brazilian singer Lenine. Basically, I was flown to Brazil to lay down my parts, and that was it. But with Nu Monda and Dor De Mar [2011], I was the producer. And also for the new one.

It's interesting that you worked with Lenine. He also has a distinctive and super funky way of playing guitar. I can imagine how he would be attracted to your sound. But you didn't think you had enough input on that record, right?

I actually did not know Lenine’s music. My label wanted to do it.

That would be José da Silva at Lusafrica in Lisbon.

Lenine and I got along really well. Very well. But I wasn't involved in the production, and when I heard the result, there were things I would've changed. It was all done very quickly.

I see. So for these other two albums, Nu Monda and Dor De Mar, you recorded with your band. How many people?

The band is five people. And I brought in some people from Cape Verde.

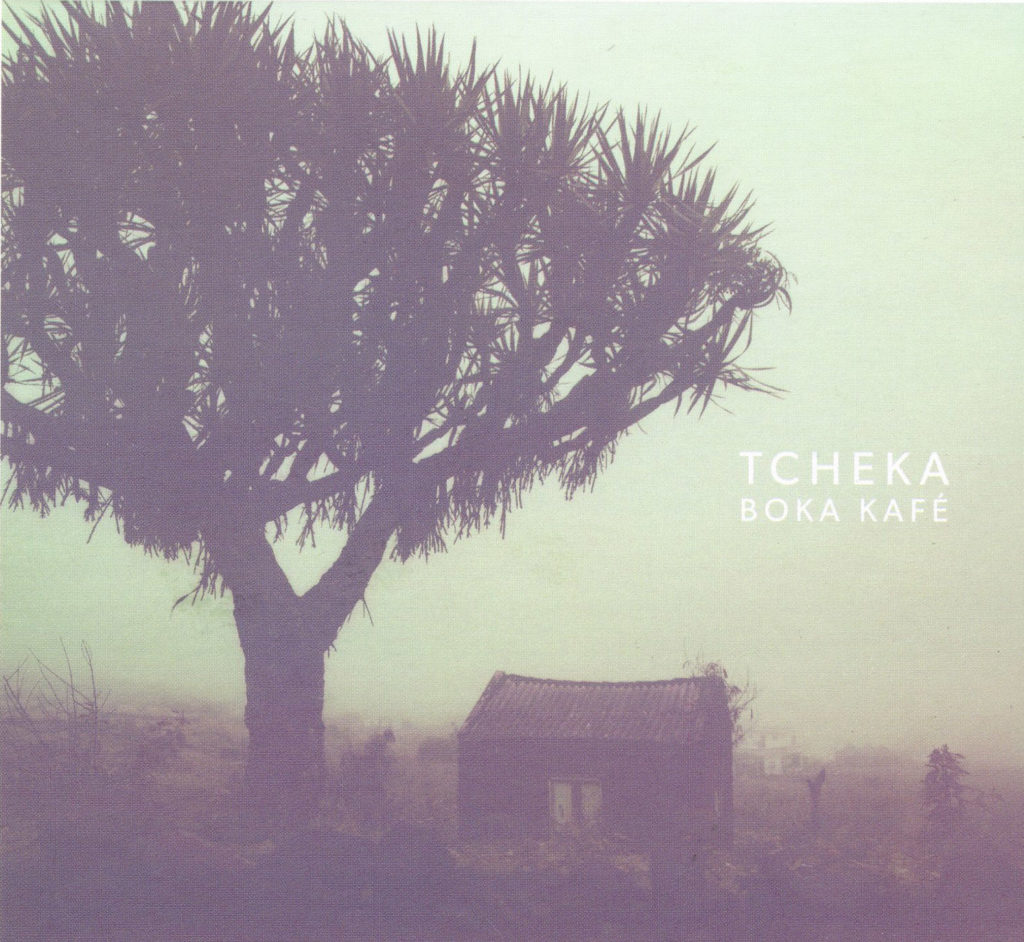

But for the new one, Boka Kafé, you’ve moved to this solo presentation, like the concert I just saw. Why are you now moving in this direction?

I didn't want to get stuck always playing the same thing with the band. An artist has to always be evolving and trying different things. So I wanted to show a different facet of what I do, without losing my originality.

Johnny Fernandes: I told Tcheka that sometimes with the band, you lose some of what he's doing on stage. Especially with the bass. We've been sitting a lot of times together and actually listening to what he plays on his own with the bass and everything. Audiences really appreciate that. So that was when he said, "Hey, let's just go and do a solo thing." It's also to try to get a different audience that is not necessarily a big festival crowd where people want to drink and dance. It's more about listening.

Great. Let's talk about the new album. Is it straight up solo? No overdubs?

It was recorded in the studio in Portugal, live. Microphones, guitar, voice. That's all.

Johnny: As you can see. There is no cover plastic wrap. Because you want to avoid plastic. This package comes from a fishing community. The guy lives 15 meters from the ocean. Because in Portugal, we eat a lot of fish, so we wanted no plastic. In Portugal, we couldn't really find these eco-covers.

Let's talk about some of the songs. Are these all pieces that you wrote? Or are some composed by others?

This is actually the first time I'm using music from other composers. Because I want to show that I’m open to collaborate, and they happened to be my good friends. The rest are mine. So “Boka Kafé”… it's really about the beauty of nature, especially on the volcanic island, Fogo.

Fogo, Cape Verde (Eyre 2015)

I’ve been there. It’s a truly amazing natural place.

I wanted to write a song about the beauty of nature and the beauty of women, using phrases from nature to describe women. Then “Pexin Pexon” is a song about the anxiety on the part of the fisherman who goes out to sea, and the family who is waiting, eager that he will come back with fish. He is saying, “Am I going to find fish to provide for the family?” Meanwhile, on land, the family is waiting. It's all about the fish.

“Strada,” the last song on the album, is the only song that is recorded with someone else. It's with the Portuguese pianist Mario Laginha. This is to give a little segue into the next album. This song is very personal to me. It's a story that was told to me by someone very close, and it's a story about a road. Strada is a road. But it's really about sexual harassment. The work gangs are used to build the roads. This is something that happened to a friend of mine. The workmen, and women, carry stones to build the road, and the foreman has a list. And he would call out one’s name so that they could get paid. But this woman is not called. And she says, "But you know I was there. Ask so-and-so. Ask so-and-so. I was there building. I built on this road. Why don't you pay me?" She's pleading with him, and he insists that she was not on the list and she's not getting paid. Really, he was trying to make a move on her. He's pressuring her for sexual favors. And she says no. So he says, “O.K., you are not on my list. You are not getting paid.” And this still happens today. Basically it's just sexual harassment.

It happened way back, and it's still happening now. I write from my own experience. Those little islands where I come from, and a very little town. All these things happen there, but they are relevant all over the world.

That song sounds a bit like a morna.

Yes. And morna comes from fado.

Songs about longing and sorrow. Tcheka, your whole life and music has taken place at an interesting time in Cape Verde's history. I've been a lot of places in Africa, but I was impressed by how much music is put forward as an identity there. You see Cesaria’s image everywhere, you hear her music everywhere. Everyone talks about her. It's not always like that. There seems to be a real respect for musicianship, and the understanding that music is some important part of identity. What's your experience of that?

Actually, from my point of view, the majority of people in Cape Verde don’t really consume that music. Not my music. Not Cesaria’s music. She's more known outside, even though she's a symbol there. But the music that they consume is not that.

It’s more like zouk, kizomba, kuduro…

That's right. And from an artist’s point of view, people say Cape Verde is known for music. And it’s true. We love our musicians, but actually, as a musician, we get zero help in Cape Verde. I just got back from a festival in Germany. I went with my album. Everybody from the prime minister down knew about it, but nothing. The French Alliance invites me. But that’s it. No one else. It's only when an artist goes outside the country that Cape Verdeans will start saying, "Hey look, he's over there. He's ours! We’re proud.” When it comes down to doing anything, that's the end of it.

Hmm. So I guess the impression I got as a visitor is somewhat deceptive. Sorry to hear that. Does this mean you don't perform a lot in Cape Verde?

I would like to. But no. Not often.

Do they play your music on the radio? Are you known by the public there?

Yes, I am very well known. If I walk down the street, people will stop me. My music is on the radio, every so often. But right now, it's a different music that is being played. A lot of younger people don't know me. Or they might know me, but they don't consume my music.

In the beginning, when you were first breaking out on your own and making your first records, you must've performed then? You had such a unique style, you must have had an audience that appreciated that. What was that like back then?

When I first started, there was a group of young people creating different kinds of music. We played at different kinds of spots where people would come to appreciate that kind of stuff. But those places don't really exist anymore. In the beginning, they did, and people liked it.

What happened to those places?

The thing is, it's very difficult to live in Cape Verde and play music. There just aren't enough places you can go play together enough to just live off being a musician. There's certainly no government help, but not even much help from the commercial side.

What about the Afro Atlantic Festival?

There is that. And Creole Jazz. I've played at those. But this is just once a year.

Let’s talk guitar a minute. What are you playing?

I am playing a Taylor 712. But this is not my Taylor. My Taylor is in the shop.

Well, you have two guitars. What do you say we go out with a little jam?

Let’s do it!

Tcheka and Banning Eyre (Johnny Fernandes)

Hear more of Tcheka on YouTube and get updates on Tcheka's music on Facebook.