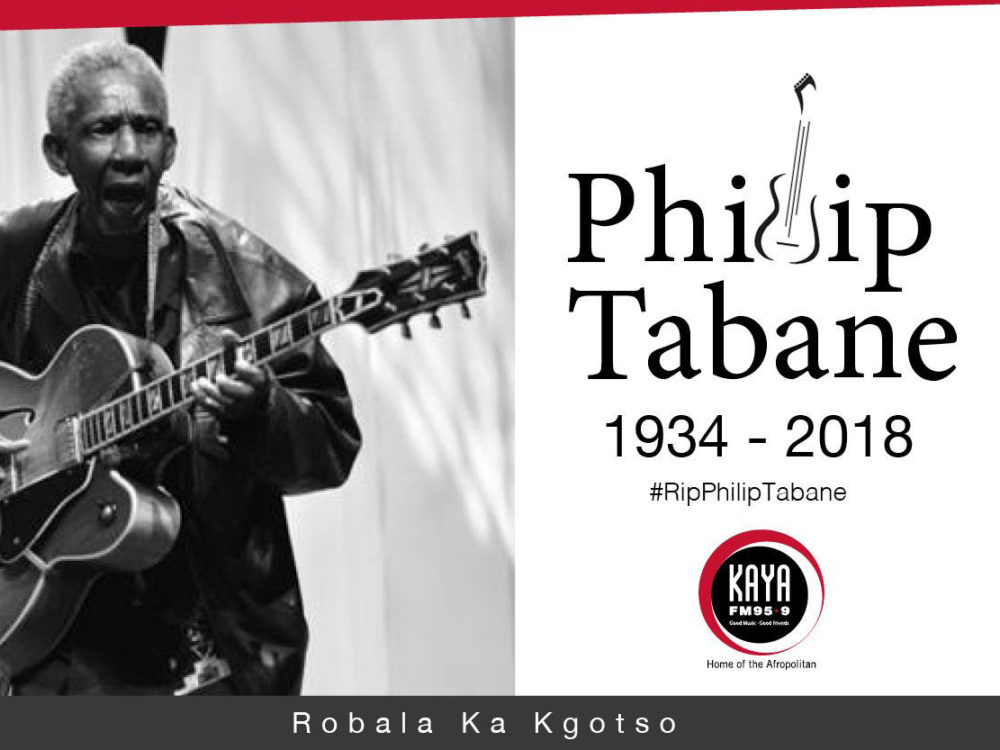

Thabang Tabane is the son of South African jazz legend Philip Tabane, creator of one of that country’s most innovative bands, Malombo. The ensemble could be as small as a duo, pairing Philip’s resonant hollow-body guitar with the large Venda malombo drum, long used in healing rituals. The original Malombo Jazzmen formed in the early ‘60s, and the group had its heyday in the 1970s and '80s. Under Philip’s direction, the group continued performing into this century. Thabang joined in 1999, playing the malombo drums, and attended his father through a long illness. Philip died at 84 in May 2018, and his passing served as a catalyst for Thabang to step forward and record his first album under his own name. Just out, Matjale (released by the Mushroom Hour Half Hour label) presents a lively reboot of the timeless Malombo formula. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Thabang by telephone to discuss the album. Here’s their conversation.

Thabang, this is Banning calling from the U.S.

Thabang Tabane: Hey, hello, sir. How are you?

Very well. I have been enjoying your record.

Thank you very much.

To start, I want to say a word about your father. Philip was one of the first musicians I ever wrote about, way back in 1988. I met him in Boston and I became a big fan of Malombo. Your father’s music was very meaningful to me when I first started writing about African music. So maybe to start, for people who don't know his story, could you just talk a little bit about your father and his music?

Yeah, my father's music was influenced by my grandmother, who was a healer, a traditional healer. She used to heal people with music. She would sing to her patients. That's where my father was influenced. So it was through the healing ways of music that he came to play guitar. Precisely, he was trained in drums. He was trained in penny whistle. And then, he got interested in playing guitar. But the influence was there because of my grandmother. That's how the Malombo music came about. Malombo is spirits, spirits of our ancestors. So all in all, Malombo music is about healing people.

I feel that. It is interesting that he chose the guitar. How did he come to that instrument? I understand that the music is deeply connected to this healing tradition, but he's using a modern instrument to do that. I think that was one thing that was so interesting about Malombo. Why did he pick the guitar?

Because also his brothers were in a musical group. His brothers were playing guitars and penny whistles, so I think when he grabbed the guitar, he had that touch. He had that special touch. So his brothers told him, "We think you must stick to this. We know you can do these other things, but you must stick to this, because you are doing it in a very different way from us. We are older than you, but your touch is very different." So that's where my father concentrated on the guitar. He never got a formal education. He never went to school for guitar. No. We just had that beautiful touch that was very spiritual. And his brothers told him, “You must play guitar.” So that's how my father just became a guitar wizard.

He certainly did have a special touch. Did you perform with him?

Yes. Yes. I have toured with him a lot. We went to Russia. We went to America. We went to France. We went, I think, all over Africa.

Were you with him back in 1988, when he came to Boston? That was 30 years ago.

No, no, no! I was still young by then.

I thought so.

One of his drummers is late. He is called Oupa Monareng. He was once sick, so my father said, “Let Thabang play malombo drums.” So we toured together, but Oupa wasn't well, so I took the role of playing the malombo drums, and Oupa was just accompanying us with conga drums. So that's when I got in the group to play with him.

When was that?

That was in the late '90s.

So you had a good long run with him. I did not realize that he had just died this year. Was he still performing? What were his late peers like?

During 2004 or 2005, that's when he started being sick, you know, on and off. I was helping him. There were gigs that I was taking, because I was starting to play his music. So I used to just take special gigs for him. Because I couldn't just take any gigs, because he wasn't feeling well. So I just took some special gigs. I played with him, so during that time, 2004, 2005, he was not getting well. I think this had to do with the passing of my mother, because of missing her and all those things. That affected him.

Of course. He was a great man. We miss him. Let me now ask about your musical education. You grew up with this unusual music, didn’t you?

I never played guitar really. I'm into drums. That's the calling that I have. Because I'm into drums. I'm also playing some piano. I'm also a vocalist.

Who is it that plays guitar on this new record?

The person who's playing guitar there is called Sibusile Xaba. I've been playing with him and I also toured with him overseas. He was a great fan of my father. So his style obviously is influenced by my father. He loved my father very much. He's the one who's playing guitar there. I'm playing the malombo drums. And I'm also singing there.

Tell me the story of this album. I read in the notes that you took a long time before making an album of your own. What made this finally happen?

I think I've always been very relaxed in terms of creating music. It was a long process. Because I played with many people, many great musicians. So for me it was just a dream all the way. I think I wasn't ready to make an album. I was really scared. Because my father, he was very sensitive. So me, well, I am a musician. But I don't call myself that. I call myself a healer more than a musician. I wasn't in a hurry to be in the front line. I was always comfortable being at the background, grounding people. But also, I knew that I can have a great impact when I'm playing behind.

So I think it was the right time, the time that this got together, whereby I got people like Sibusile, the one who is playing guitar. He's the one who said to me, "But Thabang, come. Let's do an album." Because I was helping him do his album. Then after we finished his album, he said to me, "Man, you are a great leader." He was helping me. “Do your album. I will help you also.” That's when I realized up till now this was the time. And that particular time was the time my father was starting to be sick. Then that's what I said I must accept this responsibility to take my father's music to the world.

That's wonderful. When you say that you view yourself more as a healer than as a musician, do you play in those kinds of ceremonies, like your grandmother did? Is that something that is part of your life now?

No. I think this stage is my platform. This stage is the platform for me to heal people. I don't go to those ceremonies. This is my way as a healer. My grandmother is with me all the time. So I'm thinking my ancestors are with me all the time. You know, it's like when you believe in God or whatever, for me, I don't have to go to church to say that I'm a God-fearing person. Wherever I am, whatever platform I am on, then I know one or two people I can touch their hearts.

You name to this record after your grandmother, Matjale. Tell me about her.

She was a very scary person. People used to be afraid of her because she was very arrogant. But she was loving. She was a straightforward person. And you know, we like people who are friendly a lot. But she wasn't that person. She was very straightforward. And she was very scary, but humble. Out of many grandchildren, I am the one she liked. She died when I was young, but I had an opportunity of being with her. She was taking care of me whilst I was young. Since then, I remember that when we were playing as her grandchildren, I was the special one to her. She used to call me that I must be with her all the time. So I think that's where my father saw this, that I am a boy who can take this thing further. Because no one taught me how to play drums. My father didn't teach me how to play music. But music was in me. So I think that's the calling that I had with her. With my grandmother.

Was she your father's mother, Philip's mother?

Yes. She was my father's mom.

So it's a family thing: from her to him to you.

For sure.

Tell me about the songs on this record. Are these your compositions?

These are mostly songs that I wrote, and then some songs that I took from my father's albums. I think there are two or three. The song called "Father and Mother." That's my father's song, but I also interpreted and dedicated it to my parents. Because they gave me life, and I'm grateful for them.

Then there is a song like “Babatshewenya” which is a song about xenophobic attacks here in South Africa, whereby we fight each other. So I'm just saying to people, "Hey, let's calm down. We are all one. We must not do this."

There's a song called "Richard,” which I'm dedicating to Richard Bona, the bassist. People are saying all the time, "Why Richard Bona?" I really like his discipline, you know? I had a chance of meeting him. But not really talking to him, just meeting him in France while I was playing, and he was also playing there, but I didn't have the courage to go to him, because he's a very disciplined person. So I liked his discipline, and because my father was also like that. When you are on the platform, and preparing yourself to go on stage, you don't want any disturbance. You want to collect with yourself. So that's one thing that I loved about him. And also his way of playing. He is one very innovative guy. So I dedicated this song to him.

That's very interesting. I have to ask you about the song that has the video, “Nyanda Yeni.”

Yes. There's a guy who was playing with my father named Mabe Thobejane. He is a great percussionist. He toured with my father over the whole world, only the two of them. And the sound was like they were four or five people, but there were only two. He grew up at our home. He's our relative. He knew about our Venda culture. My culture is Venda. So he is the one who taught me this song when I was with him in Cape Town. We were doing a project together. So one time we were in the town, and we were chilling, and he said, "I want to teach you a song, a traditional song from Venda.” He taught me the song and the meaning which is about asking God and the gods and the ancestors to help people in the rural areas who want to plow mealies [grains] for food. So it's a song that is talking about the dryness. So we are asking God and the gods, "Please, we want rain so we can plow and create food. Because it's dry." So it's a song of needing food to provide for ourselves. It's a song about positiveness.

What about this video? How did that come together? It's really sweet, and that old footage is quite amazing.

We were running through a lot of ideas. It's really a story about land. It's a story that's happening now about land. To eat, we must have land. So it goes further, whereby we said, "Let's make a video whereby we show a lot of racial tensions back then.” And you see my father playing there with Mabe. For us, it's just a cry for help. A cry for help.

It's very beautiful. Thabang. You know, I work with this radio program, Afropop Worldwide, and we have been presenting African music to Americans for 30 years, since the time I met your father. We listen to a lot of music coming out of South Africa, and the music has changed a lot. It's very nice to find something like what you do, that is so organic and rooted in tradition. This is the kind of music that originally inspired us. But how do you see yourself in the new world of South African music? You are obviously not a mainstream artist, but is there a place for you? Do you have an audience? Are there places you can perform? And what you think about the whole music scene in South Africa now?

As you are saying, it is very difficult, but I think I have hope. I always talk to the people around me, and there's a lot of positivity that is coming out of the audience. It's a small audience, but it's people who are young, and I'm happy that it's people who are young. Young people now are starting to realize, or to connect with this kind of music. The gigs that I'm doing now, every time I see a lot of young people who want to know about themselves, who just heard about Malombo maybe. But now they are getting that interest, to say, "No, man, we need to connect with ourselves in order to prosper." So it is very difficult in the mainstream industry. A lot of times, I'm doing shows by myself. We have some other groups that are playing. These guys who are called Aza, who are staying with me and my father. He is a young artist. There’s Naftale. There’s Vusi Mekaba. We play little places, but we organize gigs there. Young people come there. So I have hope that things will happen.

People didn't know a lot about me, but nowadays, they realize that I've been in this industry a long time ago. I was always in the background then, but also teaching. I come from my father's side, so this is the time where by now people who know at least a little bit must just share their stories, share the music, and I think young people are interested. They are very eager to know about themselves, to know about their culture. So I have hope. I have hope.

Well, good for you. That's very nice to hear. It makes sense to me that there would be young people who would be hungry for something of themselves, something out of the mainstream, which has so much foreign influence. And you are there for them. That's great.

For sure.

Do you have plans to tour? Might you ever come to United States with this group?

Yes, we must. We are planning a nice tour for next year. We have already secured London, France, and so we are still trying to connect. And I think by the end of December, will be knowing how it's going to work out, how this dream will be fulfilled. So we're working on that definitely.

Please stay in touch. We'll be waiting. I'm sure people here would really enjoy your music. It's lovely to speak with you. And congratulations on the record. It's beautiful.

Thanks for the love. Ciao, ciao.

Related Articles