Blog July 15, 2013

The 2013 Festival International de Jazz de Montreal & A Conversation with Vieux Farka Touré

This year marked the 34th edition of the Festival International de Jazz de Montreal which ran from June 28 to July 7. While jazz is, of course, the predominant form of music to be seen and heard, with over 3000 musicians from 30 countries over 10 days, festival-goers, as always, had a wide range of other genres to choose from – blues, rock, soul, and world music. Of interest to Afropop Worldwide listeners, international artists appearing included Ivory Coast reggae icon Alpha Blondy, Cape Verdean chanteuse Carmen Souza, the Soweto Gospel Choir, and Afro-Cuban pianist/bandleader Chucho Valdez. Stand out performances this year also included African-Canadian singer Lorraine Klassen's tribute to South African legend Miriam Makeba, and French guitarist Thierry “Titi” Robin with his trio who blend French Gypsy and North African music into something reminiscent of Spanish flamenco, but is definitely its own thing. Many of these shows were at the free outdoor stages set-up in downtown Montreal, which is the heart of the festival.

This year audiences were also treated to a trio of concerts featuring some of the top artists from Mali. First, a knockout performance from rising star Fatoumata Diawara. Diawara was actually born in the Ivory Coast, though both her parents are from Mali. Her music, however, is highly influenced by the Wassoulou style of Southern Mali where her family hails from. Audiences went wild for her dervish-like dancing onstage, a style which she first learned performing as a child with her father's dance troupe. In addition to her own showcase, she also joined Amadou & Mariam onstage for the festival's gala closing outdoor show. The Malian husband and wife duo were this year's recipients of the festival's Antonio Carlos Jobim Award, which honors “artists distinguished in the field of world music whose influence on the evolution of jazz and cultural crossover is widely recognized.” (Previous recipients of the award include Salif Keita, Angélique Kidjo, Ibrahim Ferrer, and Gilberto Gil.) And last, but certainly not least, returning to Montreal for his third appearance at the festival was the great Mali guitarist Vieux Farka Touré.

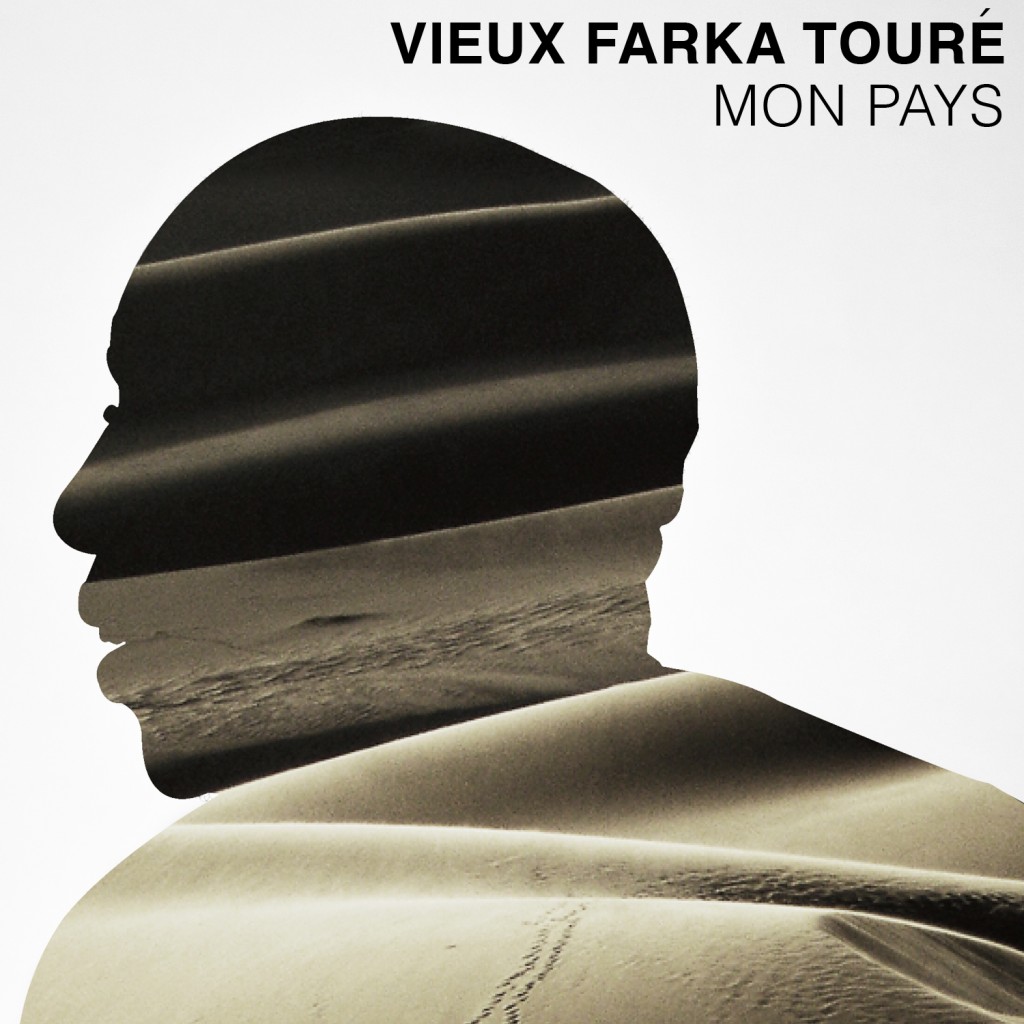

We had a chance to sit down and talk with Touré before his show at Club Soda about his new CD, Mon Pays (My Country), and the year-long nightmare his country has just suffered through. Mon Pays, as its title suggests, is an “homage” to Mali's rich musical and cultural heritage which the religious extremists and separatists who tried to take control of the country had set their sights on to eradicate.

“For a long time,” Touré said, “I wanted to record music like this, with the calabash and in an acoustic style, as my father played. So I thought, 'I have done three albums for myself, some that are collaborations with others, and now I'd like to do something similar like my father played.'” His father, Ali Farka Touré, who passed away in 2006, remains one of the most internationally recognized musicians from all Africa. “I also knew I wanted to do these songs in the tradition of Northern Mali because what I wanted to say I couldn't with a more modern sound.”

Touré began conceiving the album, he said, three years ago, way before the war broke out.

“I saw the problems happening in Libya and I knew and understood that we in Mali would have problems just like there,” he said. “I saw the war coming, but the people at home didn't see it. When you are an artist, you have to look very far out. Even when I was working on the album with Idal Raichel [in 2010], I began working on these songs.”

When the coup struck last year, most of Touré's family left their homes in the small town of Niafunke, to come to the country's capital, Bamako. And although he hired guards to protect his family from looters there, Touré said he nevertheless felt safe recording Mon Pays in Bamako.

“The extremists knew we were doing the recording and they knew what it was about because I was singing in the language they understood. But I didn't care,” he explained. “It was okay because in Bamako people were just living how they normally live, even though the war was going on outside the city.”

“You see, in Mali,” he continued, “a lot of people don't know me. There, they like to only listen to the Griot music. When I play, even in Mali, all the people who come to hear me are white, not black. Malian people don't like this music. They know my father, yes, but slowly they are coming to know me, more and more. But I see myself like a Griot, because I'm bringing word of Mali to the world. This is what I do.

“There are no borders in the music I play. It's for everywhere and everyone. Sometimes people do say, 'You are from Mali, you must play music from Mali.' 'No,' I tell them. When they ask me what kind of music do I play, I say I'm just playing music. I don't have names for what I play and do.”

In a press release for Mon Pays, Touré stated: “For me, [this album] is a statement for the world that this land is for the sons and daughters of Mali, not for Al Qaeda or any militants. This land is for peace and beauty, rich culture, and tolerance. This is our heritage, what we must always fight to protect in any way that we can. For me, that means making music that reminds the world of who we are.”

Mon Pays is filled with songs about Touré's love of his homeland, but also he pleas for a better future for it. In the song Yer Gando (Our Country), he sings: “Our Mali is a country of hospitality and fraternity, do not put it in the hands of others... Stop the differences and the criticism, for the successful development of our country.”

Of the song Safare (Medicine), written by his late father Ali, Touré explained, “It is about medication for the people. And for me, the medicine that will cure the suffering is peace. We have to stop everything – war, the bickering – and be one. We need to get the Malian people to understand that they are one people, unified, and get it together. And that is what this song is about.”

Another song on the album, an instrumental, is titled simply 'Peace.' But, understandably, Touré also harbors some cynicism about the future.

“When you speak of the politics you hear on the album, this is not the same politics of the people back home. This is my politics,” he said. “The difference is that the people get involved with political parties, who they want for president, and such. But I have no party. I am free. I'm just trying to tell the people what they have to learn – what are the good things, the bad things. And that's because to me the [forthcoming] elections are still controlled by the big heads in Europe who decide who gets to be in charge. There are no real political choices. My politics is about trying to help the people.” He added that ten percent of the money from the sales of his CD's, for example, goes directly to orphanages and to those suffering from malaria.

Touré points to another song on the new album, Kele Magne. “In this song I sing 'War is no good.' You know, before the war the government would say they want to hear what the people need but they didn't really. But then when the guys came to kill everyone, they were like 'Oh, let's talk now!' So it's important to understand that when you have power, you have to be careful. It's not when you have nothing, no power left, that you say 'Please.' No. You must have talking before, when it matters.”

Taking a break from the talk of politics, Touré noted he enjoys returning to Montreal and being a part of the Festival International de Jazz. “What the people play here, jazz, it is like the folklore from back home. It's very similar. When I hear somebody playing jazz, it's very easy for me to play with them. Jazz, blues... it's all the same. Because the music from United States and all is very similar to the music from North Mali. It's where it comes from. It's all connected.”

Vieux Farka Touré and his band will continue their tour of North America through the summer.

By Ron Deutsch

(photo credit: David Kaufman © 2013)