Samuel “Jomion” Gnonlonfoun is a multi-instrumentalist with a long history in traditional/jazz fusion music in Benin. He plays trumpet, drum-set, keyboards and percussion and he is an accomplished composer and arranger. Born in Cotonou, he started his career as an instrumentalist at age 17. He worked and collaborated with many famous Beninois groups, including Feeling Jazz (with Lionel Loueke), Gnonnas Pedro, Black Santiago, Sagbohan Danialou and Angelique Kidjo.

In 1992, with his brothers and friends, Jomion founded the world-renowned Gangbé Brass Band. This group combined horns and percussion to rework the traditional rhythms of Benin with a unique jazz touch that moved audiences all over the world. The group toured constantly, performing in prestigious concert halls and festivals such as WOMAD in London, Carnegie Hall in New York, and Couleur Café in Brussels, Belgium.

In 2007, Samuel Gnonlonfoun took on a new artistic name, “Jomion” and founded a new group with his brothers Mathieu, Jean and Jean-Eudes (J.B). Jomion & The Uklos integrate traditional instruments and songs from Benin’s Vodun religion into a jazz-oriented music with catchy melodies that are easily accessible to a mass audience. In 2012, they came to the United States, on an invitation from Harvard University. They are currently making waves in New York City, collaborating with local and international musicians, and planning the release of their next album.

Afropop Worldwide producer Morgan Greenstreet invited the Gnonlonfoun brothers over for coffee, dinner, and a long chat. You can hear parts of this interview, and music from Gangbé Brass Band and Jomion & The Uklos on our program, Benin: Transforming Traditions

Morgan Greenstreet: Hey guys, thanks so much for meeting with me to talk about your music. The theme of our program, Benin: Transforming Traditions, is how creative musicians from Benin transform traditional music, especially Vodun music, into popular and experimental music. Which is why I’m talking to you guys! So, can you please introduce yourselves?

Samuel “Jomion” Gnonlonfoun: Well, first of all, the group is called Jomion & The Uklos, from Benin, specifically Cotonou. And I’m known as "Jomion," that’s my stage name. I’m a singer, trumpet player, and drummer. In any case, we all do a bit of everything!

Mathieu Gnonlonfoun: My stage name is "Nkpa," I’m part of Jomion and the Uklos, I play trumpet, percussion and I sing.

Jean-Eudes Gnonlonfoun: Me, I’m simply known as J.B. (like James Brown!). I’m a pianist, and a singer...voila.

M. G.: Not to mention a very talented percussionist and drummer! I’ve seen the Youtube videos!

(general laughter)

M. G.: Ok, let’s talk about some of the traditional styles of music from Benin first, because it will put the transformations in more context later. Let’s start with agbadja: it’s a very popular, well known style. I knew about it before learning about music from Benin because it’s in Ghana, it’s in Togo. It also has elements that are similar to Afro-Cuban music, which are more familiar to those of us growing up in the US. Where does agbadja come from? Why is it played traditionally?

S.G.: Agbadja is a rhythm that is played in Mono. Mono is a province of Benin to the southeast, closer to Togo. I’d say the populations that are in the south of Benin, Togo, and Ghana, all the south, it’s these populations that play agbadja. And it’s often played when a very important person dies. At least in the beginning it was like that, at the funeral of an important person, like a traditional chief or a Vodun chief. During the wake, agbadja is played to bring joy to the soul of the deceased, and to bring joy to the mourners. But this rhythm is part of the south of Benin, so those people are also in Cotonou, to the south, near the beach. Every evening, if you go to a place called Klahodji there’s agbadja everywhere! That’s all that the people play there!

Ma.G.: Right by the ocean.

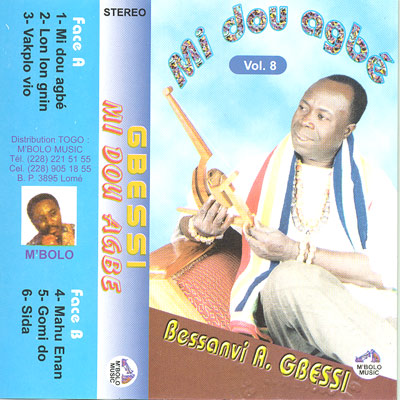

S.G.: So we had the chance to meet traditional agbadja artists in Cotonou, for example Gbessi (Zolawadji) and agbadja from Oumako, because in the beginning, before Gbessi, there was the agbadja from Oumako.

Ma.G.: That’s really the base of agbadja.

S.G.: That’s what we heard when we were really, really young. That’s what was on the radio at that time. And afterwards came Gbessi. If you listen to the Gbessi’s last album, his agbadja was modernized, because, when we started Gangbé Brass Band we put, well, I’d say, I put...because the idea for the music of Gangbé started with me...We put horns in all the traditional rhythms to be able to highlight our Beninois music. And that inspired Gbessi as well. So when he wanted to present himself for a KORA award, we added the “color” of Gangbé, if I can call it that, in his agbadja. And, happily, it worked! He won the prize for best traditional music, 2001 with “Mi Dou Agbe”

M.G.: So it was Gangbé who played on that?

S.G.: No, it wasn’t Gangbé, but, I’d say, it was the “les cuivres de la place,” I’d say the ‘sons of Gangbé,’ because when Gangbé started to develop this music, the first group that picked up on it and followed were these guys, that Gbessi invited to the studio. Because we weren’t in Benin when they recorded. So those guys put the color of Gangbé in it.

M.G.: Awesome. Continuing with rhythms: I hear a lot of kaka, kakagbo in Sagbohan Danialou’s music, in Gangbé’s music, even your music, “Azo” which uses Charlie Parker’s “Barbados.” Where does kaka come from, what is it? What is it’s traditional significance?

S.G.: Kakagbo is rhythm, among many others, from the Ouémé region, around Porto Novo. You know, all the rhythms from Benin come from Vodun. And this rhythm is played specifically for the Zangbeto, the guardians of the night. Zangbeto are our traditional police. And it’s for this spirit, with the spirit of Zangbeto that kakagbo was created. So it’s played at gatherings, Vodun festivals, and if we want to graduate initiates into this Vodun, which is called Zangbeto. And often, you see the Zangbeto themselves dancing. So, over time, kaka became a rhythm for rejoicing, for everyone! Often, when someone passes away, we play this rhythm to honor the soul of the person. It’s a very energetic rhythm, and it’s only in Porto Novo, from the Ouémé region, where you hear it. Later the Vodun traveled to other areas; it’s like how if you go to Cuba, you hear people speak of Yoruba, but it’s not really the Yoruba of Nigeria, or Benin. If you go to other regions and hear kaka rhythm, you will hear traces of Ouémé in it, but they are not from Ouémé.

M.G.: What about tchinkoumé?

Ma.G.: It’s from Savalou, a region in central Benin. We’re from Cotonou, but we’re born with rhythm in our blood, so, from the south to the north, no matter what people we meet, we adapt quickly to what they’re doing. So, when tchinkoumé is played in Cotonou, we can jump in and play, but I can’t tell you the true history of tchinkoumé, because I’m not from that region. But, when a traditional singer comes to play, we can join in and play with him, I’ll say that.

S.G.: Once, we had the chance to hear tchinkoumé played by the king, Alokpon. It’s through him that we know about tchinkoumé. Since it’s a rhythm from Benin, we’ve heard it a lot.

S.G.: Once, we had the chance to hear tchinkoumé played by the king, Alokpon. It’s through him that we know about tchinkoumé. Since it’s a rhythm from Benin, we’ve heard it a lot.

But, at a certain time, it’s necessary these rhythms become known on an international level, and it was Tohon Stan who had the spirit to modernize tchinkoumé, which became Tchink System. And, at the time, it worked, he traveled with that. But later, he didn’t continue like Youssou N’dour today, I don’t know why. He came back to Benin, and he continued playing. As well as Tohon, there were many artists who were promoting tchinkoumé in Benin, and making money! You know, to promote something, you need money, otherwise it doesn’t work! At that time, the cigarette companies gave money to promote that rhythm in Benin.

M.G.: What time period was that? What years?

S.G.: ‘85, ‘86, ‘87, around then. But, right after that, a law was passed, banning smoking. Which meant that Tohon ran out of money…

J.G.: He had nothing to invest in it!

S.G.: ...Nothing to promote big shows. Before that, he did all kinds of things throughout the nation to promote the rhythm: he presented other artists who composed in the tchink system, and he gave prizes for the best, and it worked well. But after that, it was over. Today, the king Alokpon is dead, but there are still others who compose in the tchinkoumé rhythm, modifying it bit by bit.

M.G.: And does zinlí come from the same region?

S.G.: Yeah, there’s zinlí from Porto Novo, and zinlí from Abomey, but they are pretty similar.

M.G.: And that’s played with gotta calabash drums, like tchinkoumé?

S.G.: Yes, but the traditional zinlí, is played with gotta giribo, made from clay.

M.G.: Has anyone modernized it?

S.G.: I did, in fact, with Ganbé Brass Band. Listen to the song “Ajaka” that’s the zinlí from Abomey.

M.G.: Great. So there’s one more rhythm that I hear often, but I don’t know what it’s called (plays it.)

J.G.: Ah! That’s djagbe! It’s called djagbe in Ouémé, but in Ouidah to the West, it is transformed into adja. It’s on one of our songs “Sènamè” (featured on our show, Benin: Transforming Traditions)

S.G.: We play that rhythm for the deity Sakpata.

J.G.: Check out Vi-phint. He plays very traditional adja, but also modernized.

M.G.: Great. Let’s transition to talking about your career. Let’s start with Sam, Jomion. How did you start playing music? What styles? What instruments?

S.G.: Okay. You know, before wanting to do something, I believe that thing is already inside you. So I’ll start by speaking about how I was born. That’s how I understood that I had a mission. Our father was a Vodun chief; he’s a percussionist. In life, there comes a time when each one of us needs to reflect on our lives, ask ourselves, “Where are you going?” So that moment came to my father, because all his brothers had children, but he had no children. He had done all the proper sacrifices to the Vodun and all that, but he hadn’t had any children. After that, he entered into a religion called Cherubim and Seraphim, who are angles in the heavens, but who are represented here on earth. This religion came from Nigeria, where it was founded by Moses Orimolade. So, when this religion came to Benin, someone spoke to our father about this religion, “You have no children, you’ve done all, and yet it didn’t work. Let’s try this new religion.”

So he started, and eventually he got the taste for it, without even thinking about having children anymore. He got so into it, that he eventually became a pastor in that religion. He was given certain regions to evangelize, and he started out like that. He stayed for a long time, helping people in the villages; he implanted the religion in quite a few places. But when he spoke with his father, or met his friends, they would ask after his children. “Oh, they’re there,” he would say, while he didn’t actually have any. He went home, and prayed, “God, you hear what people say. I took all my time to follow you, to praise you. Now I have no children. So that people don’t mock you, if you have one son, give him to me, I will put him at your disposition. He will play music in your church, to give pleasure to the population.” That’s how he prayed. And after that, my mother became pregnant.

And that’s how I was born. When I was young, I played at the house, until I started playing at the church. As time passed, I saw how, when there was a ceremony, they invited trumpeters to come play, to give joy to everyone. That’s how I got the taste for learning the trumpet.

I spoke to the musician who came at the time and he started to teach me to play the trumpet, little by little. And at a certain point, I’d even evolved beyond him. But I’m a truly curious person and when I started playing trumpet, and got the level of the musicians in the local brass bands, I still heard other kinds of music, and I wondered, “Can you really play all of that on this trumpet?” So I kept searching, learning, until I joined a group which played a variety of popular styles, salsa, all the rhythms...

M.G.: What was it called?

S.G.: Black Santiago.

M.G.: Right! And at the time, Sagbohan Danialou was the drummer?

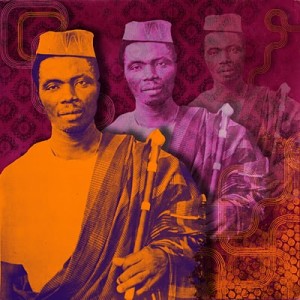

[caption id="attachment_16591" align="alignleft" width="369"] Sagbohan Danialou[/caption]

Sagbohan Danialou[/caption]

S.G.: Yes! He was the drummer.

J.G.: You know the history!

M.G.: I’m learning bit by bit. I’ve got the taste for it, as you say.

S.G.: He was the drummer in that group at that time.

M.G.: And singer?

S.G.: Yes! Drummer and singer. So I joined that group, and I started learning songs, more and more. At the time it was Louis Armstrong, the jazz we played was all Louis Armstrong. So I copied Louis Armstrong, exactly. And then I had the chance to join another group, and Gilles Loueke, known here as Lionel Loueke, was also in the group.

So I really started playing jazz in this group. I started copying Miles Davis a bit. After that, I joined a group called Caravan, and we had the opportunity to travel to Belgium, to play Jazz a Liege. And after that...Well, the band spit up, and we all went our way, and I continued to do my research. When we traveled in Europe, the music was well received, but people said, “Play your own music.” Well, we didn’t know our own music! Because we had never imagined that we could make modern music that came from traditional music. But, time passed, and we kept hearing “Make your own music.” But how? “Put the rhythms, your rhythms in the music!” So it started from that.

M.G.: But didn’t Sagbohan already do that with Black Santiago?

S.G.: Yes, exactly. But when he did that, we didn’t understand that that was really our music!

Ma.G.: That it was the right road.

S.G.: We didn’t understand. We said, “Well, that’s the music we’re used to playing.” But, down the road, we said to ourselves, “Our music is what Sagbohan played!”

M.G.: But wasn’t this the kind of music you played at church?

S.G.: Yes, but when we talk about “The Church,” The Church is not Africa! It comes from the West, and when The Church first came to Africa, we sang like Westerners. Even the trumpet, it’s not from Africa. But now, when the Vodun adepts were baptised and joined the Church, they started praising God in their manner of worshipping Vodun. And that’s how the tradition entered the churches.

And, at the time, Sagbohan played traditional music, and modern music, but separately. But he hadn’t really mixed them. And then we started hearing him do kaka with the guitar, and we said, “Voila, listen to our music!” And I would say that, even now, in Cotonou, many musicians don’t know how important Sagbohan is. He remains a huge reference for Beninois music, but even the authorities don’t know it! In the decades since Benin became a country, Sagbohan was the first person to take on all the rhythms and modernize them.

He was the first person to do that, and it’s by his example that we had the chance to understand. If you listen to our arrangements, you’ll see that Sagbohan and us, we come from the same region, speak the same language and the same dialect, and it’s really he who inspired us to modernize traditional rhythms. Which is what I had the chance to do with Gangbé Brass Band, and what we’re still doing today!

M.G.: So how did that start? How did Gangbé Brass Band start? How did you found it?

S.G.: Well, at the time, I had a lot of experience in music, and I was the oldest musician in the area who had the chance to learn jazz.

J.G.: And the chance to travel, too. And to meet other people.

M.G.: That’s important, definitely, to hear other music.

S.G.: Right, you see? So, why did the idea come to start Gangbé? You know, the way we see things in Africa is different. In the bands, all the instruments are equal, except the trumpets, the horns, they come at the last minute, on the songs where they’re needed, not like the drummer, who plays every song. It’s only in the fanfare, the street brass bands that the horns play all the time.

M.G.: What is fanfare brass band music like in Benin?

S.G.: Well, naturally, brass band music came from France! In the police bands, the army bands and all. But before that, it was in the church. We played brass music to praise God with hymns. But later, it became a group for general rejoicing, when there is a death, or a birthday, or a baby’s birth, it’s the brass bands that people call to bring joy to the people. Especially when there is a death, people call the brass band so people don’t cry too much. Now, some people in the brass bands had the idea to improve their skills and join popular music bands. But, as I said, since the horns don’t play on every song, they get paid less.

M.G.: It’s even a problem here, that the horns are often separate from the group, they’re not integrated. So they play everywhere, they don’t really want to join groups, and the groups also don’t really want to bring them in, either.

S.G.: Right! At the time, there were two of us who played in all the groups, with almost all the stars, with Sagbohan, with all the stars of Benin. It was Alfred Quenum, a saxophonist, and me on trumpet. So, we said, “We are a victims of these people, despite all our experience, despite having traveled. So we said to ourselves, “Let’s start a union that will provide horns for bands who need horns.” From there, we decided how much horns would get paid from now on.

M.G.: And horns would not play unless the price is right?

S.G.: Exactly, if you want horns on your albums, our in your group, you pay this much, and you sign a contract, and you come pay here, and the musicians come and receive their money. So we started calling people from different places, because I was at the Church, but Alfred wasn’t. So I called my church musicians, and at the time, the people came and said, "No, you have to teach us to play." “No, I don’t have time. But I have a structure which can help you.”

Mi.G.: The union was called UIVB.

S.G.: UIVB, Union Des Instrument a Vent du Benin, Union of Wind Instruments of Benin.

M.G.: Does it still exist?

S.G.: No (laughs). It doesn't. So we started inviting people, and Alfred’s older brother, André Quenum got involved. He was almost the only young guy in Cotonou who had a studio, and he had information about music, too. So he gave us music lessons in his studio. And we transmitted what he taught us to others. So that grew bit by bit like that. But now, for the practice, if the union gave the theory, it was us that put it into practice! So we started by copying Angelique Kidjo songs, with the horns, only using the horns, because that was the kind of thing we played in the brass bands. We both traveled, and when we returned, with the experiences we had on the tours, we put that into practice. And that’s when I said to myself, “I have an idea: I’d like for us to start transforming our traditional rhythms into what we’re doing, just to see, perhaps, what that’s like.” And that’s how we started, with the snare drum and the bass drum. And we played for an event that the authorities had organized. After we played, someone came to tell us “What you’re doing is good, but you should change the percussion: put our traditional percussion in what you’re doing!”

Ma.G.: He’s a professor, a musicologist at the National University of Benin.

M.G.: He’s Beninois?

S.G.: Yes! So he gave us that idea. Now we started played the rhythm, but how to do the arrangements? And there, God gave me the knowledge, and I started arranging, putting harmonies in it, and the music changed until it became Gangbé Brass Band...From the first album...

Ma.G.: ...The second...

S.G.: And the third. And we had the chance to travel with it.

M.G.: How did the touring start?

Ma.G.: I’ll pick up, let Jomion rest a bit. When Gangbé started, with the first album, they didn’t have a manager, they handled everything themselves. They sent letters everywhere, and one day, a festival in Mali invited them to play. So that really started there. And when there were official things in Cotonou, they invited Gangbé to play Angelique Kidjo songs with the bass-drum and all. And they went to Mali, to the festival, called the Festival De La Realité, and there was a group who played there, called Lojo Tribal, from France, it still exists. They played with Angelique Kidjo in London about a month ago. So, Lojo Tribal were invited to the festival and so was Gangbé. When Lojo was on stage, Sam and Alfred, being the horn players who played with all the stars in Benin, Sam started to think, to create horn lines...They weren’t invited…

S.G.: But we just got up on stage!

Ma.G.: They got on stage with their horns, and they played the parts Sam invented, without rehearsal or anything, and that surprised the guys in Lojo! And it also gave another color, another force in the group.

M.G.: And they liked it?

Ma.G.: They really liked it. And when they finished the concert, their manager approached Sam and Alfred, and said, “How did you do that without coming to rehearsal? We have an US tour and a European tour. We want you to do these tours with us.” So Gangbé’s first European tour started there.

M.G.: Touring with Lojo, in support.

Ma.G.: Yes. So they did the tour. Gangbé played first, then Lojo, then they played together. And when Lojo went on stage, the crowd called, “No, we want the other group!” And that created some tension.

M.G.: I’m sure.

Ma.G.: They handled the tension for three good months with Gangbé, and when they finished the tour with Lojo, Lojo continued and Gangbé returned to Cotonou.

M.G.: That’s the politics.

Mi.G.: Gangbé thought they would do it again the next year, but when they called, Lojo said, “No, we’re finished with you, we can’t manage these tensions and jealousy.” So Gangbé started sending letters again, handling it all themselves without management. But there was a director of the French Cultural Center who liked the music. In those days, the only place where big things happened artistically in Cotonou was at the French Cultural Center. So this guy Andre [the director] was re-instated at the French Cultural Center. So he got involved, he knew people in France, Belgium. And he said, “Why not promote this?” So at that time, there were theaters in London and Belgium who wanted to have Gangbé, thanks to Andre, and the choice was there. And since he was friends with a prominent manager in Belgium, he prefered that Gangbé go to Belgium. The manager came, they went to the studio, and that’s where they did the first album…

M.G.: Were you in the group at the time?

Ma.G.: No, I’m talking about 1999, I think. Gangbé started in 1992, with the bass-drum and all. So that took off in 1999, the traveling. Well, from 1992-1998, they did small tours, in the region, to Senegal, but Europe and the US, that started in 1999. And I joined the group in 2003.

M.G.: So after the third album, Whendo?

Mi.G.: No, I did the third album with them, so I joined before the 3rd album. In fact, I did about the same circuit as Sam. When he left a group, I would take his place (laughs). So when Gangbé took off, I took his place in Black Santiago. And later they called me to join Gangbé. He would quit a group, and I’d take it, and on and on, until, finally, we find ourselves together, here!

M.G.: Ok, so how did Jomion & The Uklos form? What happened to Gangbe?

J.G.: Everything started at the church, as Jomion told you, even before starting a professional music career, in profane music. Everything started at church. He played in church, and we were his brothers, so we wanted to do what he did. When he did trumpet, everyone in the family took up trumpet, even our older brother. So we all played trumpet, and he taught us whenever he had time. He took up keyboard, everybody started with the keyboard; he already played percussion, everyone learned percussion. So, in that way, we learned, bit by bit, to play instruments. As we were all in the same church, we sang in the same choir, we were always together. So when he did his circuit, he traveled, we shared his experiences with him a bit. And since we were always together, our spirits aligned. They created Gangbé, Gangbé took off, but at a certain point, there was a problem with the administration, which wasn’t transparent...and there was a bit of jealousy...pretty common. The group split.

Sam still kept his vision of how to revolutionize the traditional music of Benin, modernize it. That’s what he started with Gangbé. Until a given time, when he no longer belonged to Gangbé. He said to himself, “Well, there’s still a way to do other things!” When he left Gangbé, many people thought he would do another form of Gangbé, another brass band. There was a lot of tension around it, because he would need horns. So he said, “Instead of covering the same ground where everyone expects me to go, I prefer to make another surprise.” So he came upon the idea of Jomion & The Uklos, which had nothing to do with Gangbé. That doesn’t mean he has abandoned the Gangbé project; that project is still dormant inside him, and, when the time comes to do it, he certainly will!

However, the form of music with Jomion & The Uklos also gave him new experiences, new ideas. It was easier to compose with his brothers. In the beginning, he started with friends, because he didn’t want people to say he had given up and returned to his family. But, as it is always difficult at the beginning, his friends weren’t ready to make the sacrifices. They left, and he said to himself, “I have more to gain from working with my brothers.” We understand each other, we have almost the same vision, because we were always together, in the church and all. So, we believe in what we’ve set out to do, and voila, Sam brought us here today.

Ma.G.: We started in 2006. But our path here, it’s God that brought us, or if you prefer, it the force of nature. Our plan was to go to Belgium, despite all that had happened with Gangbé. We gained ground there, we played in cabarets...There’s a cabaret there, that whenever we come to Belgium, it’s our house! It’s an Ethiopian cabaret, there are only Ethiopians there.

M.G.: What’s it called?

J.G.: “Too Cool.”

Ma.G.: We wanted to return there, but I tell you, it’s the force of things. We have no force, it's the force of things. Maybe if we went to Belgium, we wouldn’t have come here! But Sam met an American girl named Sarah in Benin, and she returned to the US, supporting her thesis, which was on music from Benin, specifically Sakpata.

M.G.: Where’s she from?

Ma.G.: She’s from here, from Boston, Harvard. That’s how we came here! She had Gangbé’s CD, and that’s what interested her in Benin, and she did her thing administratively, and came to Benin. But Sam was no longer in Gangbe. It was 2005. But Black Santiago was still playing, and when he was in town, he played with Black Santiago. So, when she came to Cotonou, she went to the clubs, and there is section of Black Santiago that plays jazz in the clubs, not the whole band. And she came there, she met a pianist, Didier, the current pianist of Black Santiago. Sam came that day, he was invited to play, and Sam played with the girl, and there was an American trombonist who came, they played together, Charlie Parker stuff and all. When they stopped playing, they started talking, and Didier told Sam that she had come here because she was interested in Gangbé, and wanted to do a thesis about African music, about Sakpata. And people told her that Sam was the true Gangbé, and so they met, they talked, and the girl left. After the meeting, Sam gave her his CD. That was it, but they stayed in contact, and one day the girl said to Sam, “I talked to my professor about you, and as you make the music that I’m writing about, I’m trying to see if I can bring you when I present my thesis.” The professors accepted, and financed it. But for the voyage, she said, for the presentation of the thesis, I want your group there, but it’s up to you to buy your tickets.”

M.G.: That’s tricky!

Ma.G.: That’s why I said, it’s the force of things. She said, “You figure out your plane tickets and I’ll try to find gigs around that date. Harvard will pay this much, and I’ll look for other gigs.” It was an opportunity. So we started running from left to right, that guy (JB), he’s a serious hustler! The minister gave us a little money, and also found another way, another fund that finances artists, so we got the tickets.

M.G.: And the visa?

Ma.G.: We had no problems with the visa. We sent a letter from Harvard.

M.G.: That opens doors!

Ma.G.: But we had a little problem: The money from the minister didn’t come in time, we were going to miss the flights! So we ran all over, everyone asking their friends, “If you can give me this, I’ll get it back to you in two weeks!” We had problems! Knocking on doors, a bit here, a bit there, before the money came from the ministry. It came at the last possible moment!

J.G.: A few days before we left!

Ma.G.: If we hadn’t borrowed the money, we wouldn’t have made it.

J.G.: We didn’t even have the money for the visa application! We couldn’t apply without money!

Ma.G.: So we did all that, and nature accepted. We applied for the visa, we were accepted, and the money came three or four days before the voyage. We reimbursed everyone, taktaktak, and we take off. And when all was good, Sam said to me, “Well, I’ve already had lots of experience here. If I leave here, I’m not coming back.” I said, “It’s not that you won’t come back; we won’t come back!”

J.G.: And you know, we were invited to play a big jazz festival in Cotonou, Couleurs Jazz, Angelique Kidjo played the last one. We were invited to play, not like a small group. Angelique Kidjo was the headliner. They had three classes: the top, the intermediate, and the local groups, and we were classed as intermediate because we had traveled. At the same time as we were headed to the US, looking for money and all; so we decided to go to the States first, and see if we could return for the festival. When we got here, Jomion made his decision, “You guys can go back and do the festival without me, but I’m staying here.” We said, “No, we’re all going to stay with you.”

[caption id="attachment_16596" align="alignleft" width="491"] Jomion and JB with Angelique Kidjo in NYC[/caption]

Jomion and JB with Angelique Kidjo in NYC[/caption]

Ma.G.: That’s how we come to be here now.

J.G.: Right now we are looking for places to play, and ways for our music to be heard here. If I can brag a bit, I’d say the best quality we have is that we adapt to whatever situation we find ourselves in: If there is a drum set, we jump on it, we play, we sing, we dance. When there’s no drum set, we attack with percussion, we sing, we play, we dance. When there’s no percussion, we hit our bodies, we sing, we play, we dance! So, for us, we are a portable music making team! So that allows us to be free, to go everywhere.

M.G.: Jomion, January 10th was the Vodun Festival in Benin. I saw that you had a message on Facebook for the Beninois. Do you want to share with us?

S.G.: In fact, Vodun, in my experience...There are people, who enter into religion, the church, they ignore Vodun, or they say that Vodun is bad, and all that. But, my father advised me differently. When we began to develop our modernized traditional music, he was there, and he listened and really appreciated it. He gave us some references, and we started going to the villages, to get the advice of sages, of Vodun priests, who explained many things to us. And, from then on, I said to myself, “I spent plenty of time copying foreign music, but it didn’t give me this freedom, this...

J.G.: Authenticity.

S.G.: Authenticity, or the opportunity to travel. If I’ve had the chance to travel, it’s since I started to develop my traditional music; when we started modernizing it, then we had the chance to travel. So I want to keep that color, and develop it from now on.

I started to promote the artistic side of Vodun. The artistic side, that’s very important. Vodun, in fact, is not a bad thing! It is not the devil, not at all! If people don’t understand, they say that Vodun is the devil, that Jesus doesn’t like Vodun, but that’s false! We have never seen Jesus! It’s the westerners! And I’ve even seen videos, about the history of the missionaries in the Congo…

M.G.: That’s how they colonized Africa, through the religion.

S.G.: Right! So I said to myself, if you go into religion, there’s a bad side. In the bible, there are verses which one can use to curse someone, and it works! It’s the same thing in Vodun! So, when people say Vodun is bad...No! Vodun is not bad, Vodun is... God! Our father told us that. It’s always the same God, the same energy! In fact, Vodun is Vo du. To explain, it means “Be at ease and dance!” Around a rhythm, around a song…When I start talking about these things, there is a spirit that gives me enlightening ideas, all my own.

Because, eventually I said to myself, at church they talk about Jesus, in the tradition, they talk about Vodun; but those who talk about about Jesus at church, when you see how they act in life, it’s the same thing. I even prefer people who are involved with Vodun, because in Vodun, there are certain laws that you cannot break! But in Jesus, you can do whatever you want! So I said to myself, it’s not true! God is in the middle of all of it! God isn’t only the God of good; if God were only good, we would never know the other side. So God is also…

J.G.: The duality! The good, and the bad!

S.G.: The good, and the bad! In Vodun, it’s the good and the bad; in the church, it’s the good and the bad! So, when the church wasn't there, it was through our Vodun that we worshiped God, and it worked very well! There was no problem!

So I said to myself, “Enter into the Vodun, and begin to develop it, because it’s very important! We come from that!” When I went to the United State, I noticed something else: There are representatives of almost all the countries in the world in the United States. But what does that mean? To really have a place in the United States, you should come with your culture!

J.G.: That’s right!

S.G.: If you come with another culture, you will be erased! Our culture is the Vodun, that’s our culture. I even composed a song about it (sings). It says, “Vodun is not the devil! Leave behind your evil ways! Vodun is different from negativity! But people can be evil!” (general applause) I haven’t arranged that song yet, but the day I arrange it, I’m going to call it “January 10th” because January 10th is the Vodun Festival in Benin. And I believe that God will inspire me! I will put all my knowledge in it. For the Beninois with integrity, the Vodun Festival is really a big party for us Africans to see the source, to rejoice in our origin, because we come from that!

When our father wants to sing, he says, “When you sing, you leave the house to go outside, then you come back to the house.” In the song! It’s the same with the harmony: the tonic chord is home, then you go…

J.G.: You do whatever you want…

S.G.: And then you come back to home!

Ma.G.: Our father told us that.

S.G.: So, our Vodun, it’s our tonic chord, it’s our root. When we go to the United States, or anywhere in the world, we should always come back to the source, to reconnect, and then leave once again.

There are always people who will say, “Ah, the son of a pastor says that?” I don’t care! Because, after all, to be the son of a pastor or of someone else is not the problem, it’s how you act in life, your comportment that really proves if you are a child of God!

J.G.: Positive God!

S.G.: To be a child of God is not just to go to church, neither to go to the Vodun. It’s what you do, your actions, that must be in a positive direction! If not, you are practicing something that I don’t have a name for! A negativity! It is the negativity and the positivity that makes God! If you refuse that, well…

Ma.G.: He said it all!

J.G.: He said it all. But I would say that when you take foreign religions, and you take Vodun, Vodun is wiser than foreign religions, why? Because Vodun is on it’s own territory, which is Africa, and the other religions came, and Vodun was hospitable! It accepted Christianity. And now they teach us, who are from this earth of Vodun, that Vodun is bad, and sadly, we take that too! But I’d say that Vodun was more welcoming than Christianity, and there is more rigor in Vodun than in Christianity.

M.G.: How so?

J.G.: In Vodun, there are so many commandments that you must respect. If you don’t respect them, you will gather bad energy to you. Because, in our religion, up to the present, there are rituals that people do in their families, and they bury something in their house. As soon as that is buried, if the woman breaks the vows of matrimony and sleeps with someone else, the thing you buried can kill you. No, it will surely kill you! Because it was made for that! Whereas, in the West, she can return to you and say, “I changed my mind.” Vodun is really rigorous with certain things. But all that is too bad, because today, people who are born from Christianity, I mean white people, are now coming to learn the tradition, the culture of Vodun!

Mi.G.: There are even white Vodun priests now, in Benin!

J.G.: That’s right! And today, Sarah comes to Benin, to study Sakpata, and she meets Africans there, Beninois, who she wants to be friends with, to better understand, and these Beninois, tell her, “No, we are Christians, we are not involved with that!” That’s too bad! If we go into that debate, we could go so far…

We are the sons of a pastor, and I’ve never been ashamed to say it. And he has been more or less straight his whole life, and he taught us like that. And we also don’t have any shame to say that Vodun is for us! Benin is the birthplace of Vodun...But as soon as we say Vodun people think of witchcraft, etc.

Traditional gospel music, in Benin, even uses the Vodun rhythms to worship Jesus! (sings) That’s one of our father’s compositions. It’s gospel, but not African American gospel! It’s traditional, and we play a Vodun rhythm with it! We cannot disconnect ourselves from that! Because, before the Western gospel, our gospel was the djagbe, tchinkoumé, agbadja… So when the gospel came here, we couldn’t play swing, we couldn’t play jazz, so we worshiped the new God they initiated us into, through the rhythms that were nothing else than traditional Vodun rhythms. We took the rhythmic side, the cultural side, the positive side, to worship that which we called God. So we can’t separate ourselves from that! We will never be America or European, we will always be Beninois! And we know that our cultural riches, that which makes us who we are today, is Vodun, because that’s what we bring with us. That’s the difference between us and you, American! And we’re proud of it!

[caption id="attachment_16601" align="aligncenter" width="581"] Egun-gun Masquerades[/caption]

Egun-gun Masquerades[/caption]

M.G.: And Americans like myself or Sarah can find beauty and good in Vodun, in your culture! We will never be Beninois, but we can enter into it a bit!

Ma.G.: Exactly! It’s like that!

M.G.: Are you planning to do another album?

Ma.G.: Yes! Actually we already did a little thing in Belgium with 6 songs, each one of us brought two songs. But since we didn’t return to Belgium, we’re trying to get the engineer to send us the tracks so we can put it out here. We’re working on it, we’re waiting.

M.G.: Okay. Is there anything else you want to say? I have more than enough information for this show, but I think this is just the beginning. Are there groups like you in Benin? Kaleta (of Zozo Afrobeat) says you’re the best!

S.G.: If we’re the best, it’s not up to us to say so!

Ma.G.: It’s up to you to figure out. I’m Beninois, I grew up at Cotonou, it’s the capitol, like the New York of Benin. And I’ve noticed, when a new thing arrives, people throw themselves at it, without waiting to understand the logic of what they’re going to do. When Sam started doing Gangbé, this was a new thing. No one had done this in Benin. But when Sam did that, all the fanfares, everyone started doing brass bands. In Cotonou, we had more than three, four, five brass bands.

J.G.: Six brass bands!

M.G.: Wow.

Ma.G.: Because people traveled with that, and everyone wanted to travel. When you embrace something, people don’t come to see what the basis is of what you’re doing, they just copy what you do! That was the case for Gangbé. When Gangbé started traveling, everyone started a brass band! Brass band here, there...But when we quit, and people started realizing that Gangbé was changing form, all those brass bands disappeared. And, as JB said, they thought Sam would start a new brass band, but Sam surprised them! But, to speak frankly, the road that we’re on, right now, no other group has started on that! You can go there and hear all kinds of music, but this kind that we do here, we’re the only ones.

M.G.: I believe it. What about the Freres Guedehoungue?

Mi.G.: Their father, Sossa, was the head Vodun priest in Benin, it seems. Their father was the president of all these groups, he did sacrifices for the president of Gabon, Bongo, who is now deceased. So Sossa went to Gabon to do sacrifices from time to time, so he had money and lots of wives, and lots of children who didn’t even know each other! So they took over, from their birth, children of Vodun. What they do is Vodun, but it’s not the same as what we do! You will see many things that connect to Vodun, but not the way we do it. Right now, in Cotonou, the musicians who stayed there, who were with us but didn’t have the patience to stick with us because they wanted to earn money right away, now they write Sam and tell him, “Since you’re gone, music is dead in Benin!” They don’t know what way to go anymore, because we’re not there! Now they write Sam and ask him to return, but when we were there, they didn’t take us seriously!

M.G.: It’s as they say, the prophets are never heard in their own village…

Ma.G.: That’s right.

M.G.: Well, thanks you guys so much, it’s such a pleasure to talk with you!

Ma.G.: For us too!!

[caption id="attachment_16606" align="aligncenter" width="614"] Jomion & The Uklos at Harvard University, teaching a masterclass[/caption]

Jomion & The Uklos at Harvard University, teaching a masterclass[/caption]