Wills: What do people call you in Nigeria? What’s your nickname?

Lancelot: They call me the Governor, and I’m also a United Nations ambassador for peace. My real name is Lancelot Imasuen and I’m a Nollywood filmmaker. Right now we’re at the O’jez restaurant, inside the premises of the national stadium in Surulere. And coincidentally Surulere plays host to Nollywood in Nigeria -- the start of Nollywood was actually here, within these environments in Surulere, Lagos.

Wills: Why do they call you the Governor?

Lancelot: The actor Ejike Asiegbu gave me that name in the year 2001 during the filming of a movie. I think he noticed my artistical, directorial prowess, and he screamed the name “the Governor” while we were on set. It just got stuck.

Wills: What is it about your character that makes you a good fit for being a Nollywood director?

Lancelot: My character is passion. I’m very passionate. I’m a determined soul. That has been evident in the kind of works that I do. People say to me: “Hey, you are not an actor, why are you so popular?” Well, I’m not the face in front of the camera, but by the grace of God, and because of the passion and determination that I put into my work, this has all endeared me to so many people to wanting to put a face to the name.

Wills: Do you have a favorite genre to work with in Nollywood?

Lancelot: No. I just want to be known as a filmmaker. I’ve made epics that have been great hits -- there’s one presently suffocating everywhere now called Adesuwa. It is a traditional epic. I’ve also made contemporary movies, love stories. I’m just a filmmaker.

Wills: How do you deal with historical narratives and the dramatization of history?

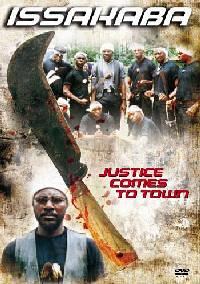

Lancelot: I’m from Benin State and historically that place has one of the richest cultures in the whole of Sub-Saharan Africa. We have a lot of history that would make for great dramatical work today. So I started with Isakaba, which was set in 1752 A.D. It’s about lust and greed. I’m trying to connect some of the political, social problems we're having today in Africa, to the past. Has there been any growth? You will see me treating the issue of corruption in Africa through my historical epic: a king sees a beautiful girl, and says that he wants the girl. He doesn’t know this girl is betrothed to another king! And he says he can get the girl through all the means available to him. He ends up plundering his people into chaos, killing himself in the process. All hell is let loose.

I also just filmed Invasion 1897, which is a deliberate attempt to attract global attention to the issue of repatriation. In 1897, the British government carted away billions of pounds of traditional artworks from Benin state. These are the history of a people, the records. We have a lot of bronze work; we have a lot of wooden carving, a lot of ivory casting. These were the materials that were carted away. So this movie is deliberate statement about reparation. It’s not just a movie.

For me, when diving into a historical film, it must have something to do with the present. Not just for the sake of drama. We want to stamp our existence on the sands of time. We’re looking at important topics in order to liberate our people, and to give them the compensation that they need.

Wills: How important is accuracy in terms of telling historical epics in Nollywood?

Lancelot: When we started, the academics and the film school scholars, they never saw anything good in what we were doing, they were criticizing us. But the industry survived. It’s gotten global attention. Now a lot of film school scholars are working with us.

Wills: Let me try to ask my question again: have people have criticized your films for being inaccurate?

Lancelot: Sure. The majority of criticism we get is like, oh, this was not a cap that was used then in 1752. Or, 1752 there was no zinc roofs. But you cannot find those places like they used to be. You know we are limited sometimes in terms of resources, but we want to make sure we are telling a factual story that cannot be denied in time.

Wills: Some of the world’s attention is on Nigeria right now because of the fundamentalist group, Boko Haram. Do you plan to address that situation in your work?

Lancelot: Sure. In time, generations as yet unborn will have to also know that we're besieged by such an experience. Once it is resolved, we will be able as filmmakers to document some of these things for generations to come

Wills: About how many people does it take to make one of your movies nowadays? How many people do you employ?

Lancelot: In my recent epic work, Invasion 1897, I had about 64 crew members, and had over 500-1000 cast strength on the set.

Wills: Can you tell me about how the revenue comes in, from what streams?

Lancelot: When we started, it was purely from the movies, but today, I’m talking with advertising companies that want to get their product placed in my movies. I also do commercials, music videos. Shooting movies for cinema (not just for video / DVD release) is important right now. Cinema is dying in other places but here in Nigeria, we are the champions.

Wills: Tell me about your inspirations.

Lancelot: I’m inspired by the Nigerian society. I remember the first fans of my work. I don’t want to disappoint them. I want to do more. I always want to do more. I remember when I made my first film; it was in Igbo language and many people said to me, “Hey, you don’t understand that language -- how did you do that?” I said, “Well, movie drama is universal.”

I always compete against myself. I’m very passionate about what is happening in Africa. I believe it can change. I believe we can get the right leaders on board. I believe that things can go well. I believe that my films will be reference points for the future building of Africa.

Wills: What other artists inspire you?

Lancelot: My idol is James Cameron, but my biggest hero is Richard Attenborough, the man who made Gandhi. It’s because I’m so interested in historical epics.

Wills: What are some of your predictions for where Nollywood is headed as an industry?

Lancelot: I have a mind for the future. I’ve been around the world, visited about 20 countries for Nollywood. Nollywood is a moving train that there is never going to be any stopping. We started from the end point of most other films – home video distribution. But now cinemas are coming and now we are doing it the way the entire world does it. There is a great future in Nollywood; we just need an enhancement of the infrastructure here, some assistance from the local government to bolster Nigerian film culture.

Nollywood is a major and essential force in the fight against American media imperialism. Through it, Africans can begin to regenerate ourselves, to create our world, to use these movies to propagate true gospel and the enrichment of our culture and heritage. My movies are a medium for social rebirth.

Wills: Talk to be about how the star system works in Nollywood.

Lancelot: You see the problem with Africa is that we admire people who leave their house, who abandon their house. Nollywood has birthed icons and brand ambassadors -- companies come and take these individuals out of Nollywood; they neglect the house that produces these individuals. They are not thinking of how to sustain the industry as a whole.

Wills: Let’s talk about the role of religion in your films.

Lancelot: I don’t want to force people to be in line with my religious belief, but of course you see a reflection in your artwork of yourself and of your beliefs. Religion is not too paramount, thought. There are no lazy resolutions with my story lines -- diverting to a religion can sometimes do that. For me, the story comes first. I love my stories to dictate their own resolutions, to anchor the stories without any religious bias.

Wills: Do you think Nollywood has done a disservice to traditional religions?

Lancelot: Yes, you can call it disservice, but everybody is at liberty as artist to make his or her own statements. Also, you must remember that Nollywood is commercially driven. There are no grants here, no film funds. You don’t get loans from the banks to make movies. So everybody tends to say they are Christians in Nigeria. It’s a society of do what I say and not what I do. Directors are looking for patronage; they want to follow the populist angle. And that’s why you see the Christian religion dominating most times. The actual belief might just be superficial. Christian films have massive amounts of followers.

For me, as a Christian, to satisfy that side, I have a company that only produces gospel films. Then I have my company that does my secular films. So I do both. I just made a Christian film called Christian Heaven, for Christians and people that want to be born again. And I am still free to look at socially relevant issues in our society using my secular company.

Wills: Why do people love Nollywood?

Lancelot: Nollywood is life, like I told them on CNN. When the film is fake, when someone is fake here in Nigeria, when someone is lying, we know. Arnold Schwarzenegger cannot carry machine guns around and kill everybody. It’s not real. Why people love Nollywood – Africans, black people all over the world – is because of the stories, because they can feel the pains with the characters. The movie takes you into itself. When you see people in the movie crying, you start crying because you have a cousin, a friend, a sister that is probably going through the same experience that the film is portraying.

There’s also a fantastic documentary called, Nollywood Babylon, which features Lancelot; it’s available here on Netflix.