Avi Salloway is a guitarist/singer-songwriter/bandleader in Boston with an unusual story. A musician since early childhood, he planted his flag with the creation of his band Billy Wylder. But soon after the band released its debut album in 2013, it went on hold while Salloway spent three years touring the world with the acclaimed Tuareg singer/guitarist Bombino. This was during the heady years of Bombino’s rise to global fame, not an opportunity one passes up! But Salloway returned to his band and produced another album in 2018. This year, Billy Wylder is out with an EP called Whatcha Looking For Afropop’s Banning Eyre spoke with Salloway about his story and the new music.

Banning: There are a lot of things I want to ask you, but let's start with this. Why is the band called Billy Wylder?

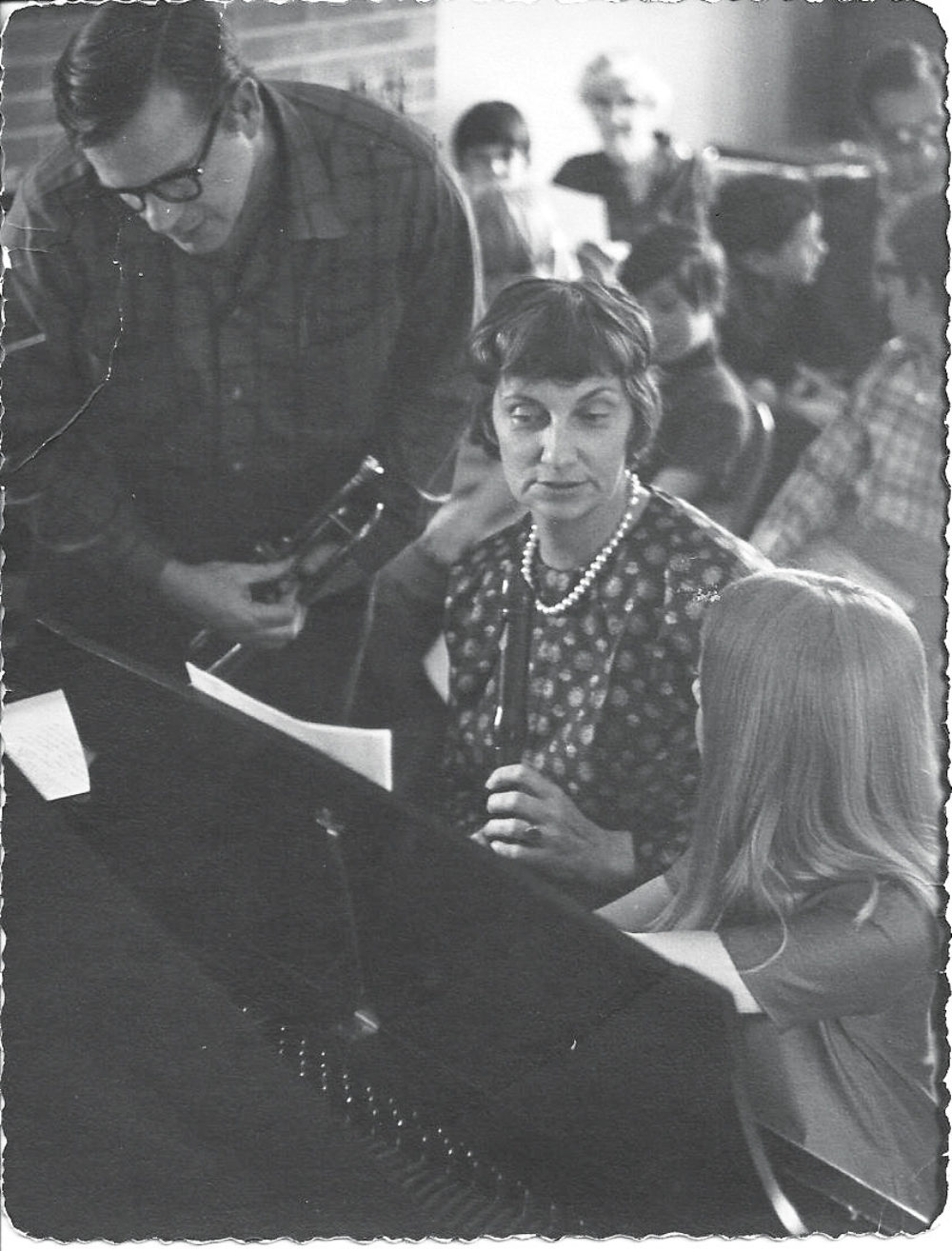

Avi: Great question. I named the band after my grandmother, actually. She passed away several years ago, but her name was Billie and she had this big influence on my life. She was an artist, an activist, an author, an educator, a painter, a musician. This is a picture of her right here. She's playing the bass recorder in this picture.

She just had a profound influence on me. She had this progressive, wild spirit. So I paid homage to her name, "Billie," and combined it with that wilder kind of energy that she had. She was really creative at using art and music and education as pillars of resistance in creating change. That was very inspiring to me. It is kind of woven into the ethos of my band, the idea of really exploring the power of music beyond entertainment.

So, nothing to do with the director [Billy Wilder].

No. Although he was a great director. And I've enjoyed watching some of his films. Some Like It Hot. That was great.

Indeed. So let's talk about your early years. How did you get your start in music?

I started violin at a young age. I was 8. Both my parents played music, and several family members, my grandmother and grandfather and that whole side of the family. So music was just kind of a thread in our household. I started to play guitar when I was 9. My dad played guitar, and I picked it up, and within a day or two I could play chords and sing a song. And I was like, "The violin. That's all right. But I like this guitar. I'm a one-man band in a few days here. I think there's a lot of potential." And then that summer I started going to Camp Killooleet, which was run by Ellie and John Seeger, Pete's older brother. So I got this amazing education in American folk music and the breadth of American folk music, the real deep roots.

I started to play Mississippi John Hurt and the Carter Family and Leadbelly and all these things, kind of learning from the main sources that were connecting those artists with the present generation. I got to play with Pete as a kid, and then also as an adult so that was a real education in American folk music. And then I started to discover rock ’n' roll and jazz and all these things. I started a band in middle school when I was 12.

I just started creating this culture of bands and music and writing music. I went to University of Vermont where I continued that, studying music and business, and forming another group called Avi and Celia, later Hey Mama. We started to tour and do our thing. That band probably played 500 concerts in six years. So I was just loving the culture of creating music.

At some point I decided to take break from that group. I was going to the Middle East to work on this project with Palestinian and Israeli youth musicians, building consciousness through music and collaboration. And that's where I first was introduced to Bombino’s music by Ravi Kahalani, the singer from Yemen Blues. Do you know that band?

I do. I’ve interviewed Ravi. Great band.

He played me this clip by Ron Wyman that he had filmed in Agadez right after the second rebellion.

This is the filmmaker who first documented Bombino and effectively launched his international career.

Right. And I was just mystified. I was already into West African and North African music. But seeing this guy and his band playing in such a revelatory moment after years of exile and depression and being displaced. I was transfixed and I started to transcribe a lot of Bombino’s music and Tinariwen. I just fell in love with it and the culture. Then I moved to Cambridge and became friends with Ron Wyman, who was like, "Oh, you’ve got to meet Bombino." Ron was the guy who introduced us and we ended up jamming late into the night. We had very little common verbal language overlap. But we had a very strong connection musically and spiritually. That was the beginning of our friendship, which then eventually led into me joining the band, which was kind of a dream come true.

How long ago was that?

First hearing Bombino was 2011 in Tel Aviv with Ravi. And I think it was either later in 2011 or 2012 when I had that first meeting with Bombino. And then in 2013, I was asked to join the band, first as tour manager and playing a little bit, which evolved pretty quickly into playing guitar, calabash and singing in Tamashek. It just kind of spiraled from there. All of a sudden we were touring five continents and playing hundreds of shows a year. It was kind of a cosmic exchange that happened through this musical thread of following and exploring.

So you guys literally started jamming from the first time you met?

Actually, we met in Boston at Johnny D’s. RIP Johnny D’s! [The legendary Somerville nightclub closed in 2016.] And then I think it was a few months later there was a benefit Bess Palmisciano arranged for the organization she founded Rain for the Sahel and Sahara. Bess was the one who introduced Ron Wyman to Bombino. They had this big benefit concert in Portsmouth, Maine. There was a screening of Ron’s film Agadez: the Music and the Rebellion. That was really the night that sealed the deal for me and Bombino bonding and hanging out through the night. I'm just so grateful for all these serendipitous connections.

So connecting that to Billy Wylder, I had just recorded the first album with my band, Sand and Gold. We released it in May 2013. And then, a month and a half later, I got the call, "Do you want to go on the road with Bombino? We're opening up for Robert Plant on this tour. We’re playing Newport…” All these pillars of performance opportunity. I had just been totally charging up into launching my own musical outlet, releasing this album and touring. And I had to make a tough decision to put that on hold to really explore this opportunity with Bombino.

I have no regrets, obviously. It was incredible. But little did I know that it would be over three years of touring all over the world with this guy, going to Niger with him, New Zealand, Australia, Brazil, all these amazing places. So I decided to put my own project Billy Wylder on the back burner. Then it was about 2016 when I was feeling really energized to pursue my own writing and my own creative project, and I had to make another difficult decision to step back from Bombino and be able to focus more on that, and also with my partner here in Boston which was obviously challenging with the amount of touring with Bombino.

Wow. Three years on the road with Bombino. I imagine you picked up a little French along the way.

Yes. Un petit peu. A little bit of Tamashek, and I knew a little bit of Arabic too. So we kind of created this mélange of four verbal languages in which we communicated. It was pretty unique. I think the people who might've popped into our communication bubble couldn’t follow it, but within the band we had a really tight rapport with actually limited overlapping vocabulary—maybe 200, 300 words. I don't know. Something like that.

So what was the point when you decided he had to pull back and focus on your own project?

It was right at the end of 2015. I was already starting to write a new album of my own and feeling really inspired. And then it was the beginning of 2016 when I formally decided to stop touring with him and focusing on my own stuff. That was a hard choice, man. It's such an incredible, soulful experience to get to learn from these guys that are carrying this epic tradition and inventing new things and connecting to this whole other world. I am forever grateful for that, but I think it just naturally started to fuse into my own musicality. I'm sure you can hear that in some respects. It was kind of connecting the dots of this cross-continental inspiration of music, coming back to the sources of American music that were formed originally by the African diaspora, and then getting to play the next development of those musics on electric guitar with Bombino, and then starting to weave that back into my own American roots. It was a very seamless, organic flow.

It's so interesting the way the music from the Sahara and the Sahel feel so continuous with American traditions. I'm sure the people who created the sound in the Tinariwen generation felt it. It was perfectly natural for them to pick up electric guitars, and then they created a sound that proved to be so resonant in American ears. Afropop covers so many different African genres, and that one really stands out for its ability to translate. Never mind the robes and turbans; people heard it as a kind of rock ’n' roll. I'm sure you must've thought about that with your strong background in American folk music.

Definitely. It felt like the grandfather and the child at the same time, and to play that music and connect it with Delta blues and stuff that I had been learning as a kid, Appalachian music, even some Celtic music. There are overlapping musical storylines, pretty beautiful stuff.

I always think of it as twins separated at birth and then reunited down the road.

Yes.

And what's your sense of Bombino’s experience of that connection? Was it surprising to him as well?

I can't really speak for him about that, but I do have a very distinct memory of one of the very first shows when I was on the road with him and we were opening for Robert Plant. Here I was 27 or 28 and I was hearing Robert Plant sound check “When the Levee Breaks.” And I'm like, "Holy s%$#!” I'm like five feet away and I grew up listening to this crazy music; the huge drums of John Bonhem. And here's the guy doing that. I remember talking to Bombino about it and he was like, “Yeah. It’s pretty good.” I'm not saying he was dissing it, but it wasn't blowing him away. He didn't have that history obviously, the direct history of listening as a kid and being mystified by that sound. It was just kind of a humbling moment for me. For this dude it was like anything else. Pretty good. He wasn't floored or super impressed.

That's fascinating. It reminds me of the Festival in the Desert in 2003 when Robert Plant was there. I'll never forget watching him play for this mostly Tuareg audience. It was a bit similar. They enjoyed it, but they didn't really have a sense of who this person was or how unusual it was. We did an interview with Plant then, a very good interview. I was impressed by how thoughtful and reflective he was about all this stuff.

Yes. He personally was honored to have Bombino on the road opening up for him. He was very respectful and honorable towards him and the band, me by extension. That was very cool. I mean this guy was one of the kings of rock ’n' roll and electric blues.

And with his past reputation, you wouldn't necessarily have expected that.

Right, right. I've met other heroes of mine who didn't live up to that level of respect.

He's solid. Very good guy.

Let's come back to Billy Wylder. How many recordings have you guys made?

Well, after Sand and Gold in 2013, I joined Bombino on the road. So then our next album, Strike the Match, came out in 2018, and now our forthcoming EP comes out next month: Whatcha Lookin For.

The video for that song is already up on YouTube, right?

The title track, yes. We’re rolling out the music in a very 2021 fashion based on how people consume music. So we’ve been putting out a single a month starting in January. The whole EP comes out in April.

Cool. I hear all those influences coming together in the new songs. One thing I have to tell you. As a guitarist myself, I'm really impressed with the richness of guitar sounds you have going on.

Thanks, man.

Gorgeous tonalities. And that's something I noticed with Bombino. He always had a great sound, but after he did the Nomad album he made with Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys, his sound really took a quantum leap forward in terms of richness and depth.

Totally.

So let's start there. Sometimes it sounds like there are three guitar parts happening at once, each with its own identity. Talk about the evolution of your approach to guitar sounds.

Sure. Well, to clarify, what you may be hearing as guitar is Rob Flax, my bandmate who is an incredible multi-instrumentalist. On the title track, he's playing pizzicato violin through a Fender Champ and a Fender Deluxe amplifier. Also through pedals, getting almost this kind of electric ngoni, Bassekou tone. So that's one of the elements. And then on the title track I am also playing this guitar loop, which is kind of the fundamental loop that plays throughout the song. And then on top of that, I'm playing the live performance of the guitar which we tracked as a band to that loop track.

There is so much to be expressed in tonality. Obviously the notes you play, the rhythms you play, the feeling, but then a lot of that can be really enhanced through different sonic treatment in terms of pedals and amplifiers and engineering to achieve the sound you're going for, the story you are trying to tell through your guitar. That's been a fun journey to really explore that. I actually tracked down this old Gibson 1950s amplifier from a friend specifically for this recording because I knew that was the sound I wanted. So I played that in stereo along with my staple amplifier, a Fender Blues Junior.

I love that quest of uncovering and discovering sound and exploring with that. And my bandmate Rob Flax, a really ingenious guy too, has been on the journey too, and you can hear it in his sound.

Do you have one guitar that you particularly favor or do you always use different ones?

I have a lot of guitars. One of my favorites is this Guild Starfire 5, 1965. It's similar to the Gibson 335 idea, but it definitely has its own personality. When I was 12 years old I got this Fender American Stratocaster, kind of a classic guitar that I still play every day, probably most days since I was 12. It's just become another arm. Then I have this tri-cone resonator guitar that I play a bunch, and I played two of my dad's guitars that I was lucky to inherit. One of them was originally from my grandmother, Billy, an old Martin classical guitar.

Beautiful. A fine collection. The song where I felt I was really hearing a lot of guitars was actually "Sahara," the instrumental song.

I wrote that composition while I was touring with Bombino, and you can definitely hear that Tuareg influence in the groove, in the melody, and the inflection of the playing. It was really fun to explore that with my band. Our drummer Zamar Odongo is from Nairobi. So he's coming from this East African tradition, but then he moved to Boston and spent some time at Berklee, and has some breadth of experience. So he really understands a lot of the language of the music and was able to adapt a Tuareg influence mixed with his background, which was cool. We tracked that completely live with the addition of one guitar part that I added after. It's like a background guitar counterpoint. But that was tracked live with the four of us: guitar, pizzicato violin, with the amps, bass and drums.

It's a beautiful sound.

“Sahara” is actually the first instrumental this band has recorded. For the others, the lyrics are a critical part of the song. Thematically this EP is really a reflection of this moment. I see this as an opportunity for rebuilding—a rebuilding moment versus returning to the status quo that we had been living in, which I don't think was serving a majority of the people or species on this planet in terms of the way we've been operating, and the systems we've been living under. They are just not serving us to live in harmony with the planet and each other. So “Whatcha Looking For” is asking just that: What are we looking for? What are our priorities and what are the perspectives and sources of information that are guiding us, and do they serve us or do they not? It's kind of looking at the histories and how we want to re-pivot and explore our shared future together here on this planet.

I'm a pretty organic songwriter. I don't come up with a topic and try to write a song about that. Nothing that dead-on. It's more of an organic uncovering of songs through stream of consciousness. Free writing. Exploring both music and lyrics together, and then extracting ideas through that kind of creative process.

Is there any rule as to whether you start with music or lyrics?

Usually it comes out of an improvisation that is both, without any commitment to either one. It's more like I try to create a liberating free space to do that. Sometimes I just press record and do two hours of playing and improvising and then listen back to find what was memorable and distinct out of that. Sometimes there is great stuff. Sometimes that was just a cathartic moment of improvisation and there's nothing that I want to work into a song. Usually, I will get certain phrases of music and concepts through that initial process and then further explore those and develop more of a fleshed-out melody, a form, a concept of how the song all fits together, and then I develop phrases into actual lyrical narratives that seem to be in harmony with the music. So it's a layered process for me.

I relate to that. I do a fair amount of late-night guitar improvising into a microphone hoping that some pearls will spill out.

So you write too?

I do. I actually had a career of sorts as a singer-songwriter for about 10 years, long before the Afropop time. But I wasn't much of a singer, and I never found people to sing my songs that seemed satisfying, so I’ve pretty much stuck with guitar since then. But I still compose instrumentals.

That's awesome.

So, let's talk about your song "Santiago."

Well, I had come up with the basic melody and chord progression and the groove and just started to riff singing. I started to sing what became the first verse:

There's a brass band in the street.

I swear it's not in my head.

Won't you come meet me?

We'll dance with the dead.

It's Sunday in Santiago and the beat is real loud.

We take it to our bones. It's heard high up in the clouds.

This was around the time of the more recent revolutions happening in Chile. And I think that just kind of subconsciously started to weave its way into this song. And then the song grew into something well beyond the country of Chile and Santiago. I started exploring the duality of man, the darkness within each of us, and kind of coming face-to-face with that so that we can actually address it and start to grow from there. There's a lot of shying away from the darkness within us and within our adversaries that we seem to distance. We are so polarized and always pushing each other further and further apart, and in this song, the singer comes face-to-face with the devil in the fourth verse:

I saw the devil in a dream and he lived in a white house.

Fear was his only weapon and I could see through his doubts. So I looked him in the eye and asked him to oblige.Played him this song, and he sang along to my surprise.

So here, the devil is joining in on your own song, singing along, closer to us than we realize or think or actually come to terms with. And then there's the fifth verse:

We witness the madness as if we're far beyond the crime.

Laughing at the sadness, we distance our own kind.

There's a story in our bones that can't go ignored.

We are more like our enemies than we believed before.

And that's the kind of meeting point at the fire in the video, with all these different mystics, the dancers coming together and singing together, “La da da da. Da da.”

That video is remarkable. Tell me more about it.

It was so cool to make that video, especially during the pandemic. We were able to pull this off, all getting tested, getting these creative people together in a place in a safe way. I had met those dancers the day we started filming. So it was a pretty organic creative process in building this kind of chemistry and trust in the moment. And they were so hungry to dance and perform. A lot of them are full-time artists, performers, and it was just a reminder of: Wow, common humanity exists. We’re here together. I'm feeling that urgency to create and share music and art in this time when we’re facing great despair and isolation. I really think music and art are the means of bringing people together, but also transcending through pain and loss and creating a more beautiful existence. So it's exciting even though we are not able to be on the road touring, which hopefully sooner than later we will be.

That “Santiago” video begins in an interesting cabaret setting with you standing on stage in a maroon suit with an acoustic guitar and a lighted crescent moon behind you. Where was that?

I wanted to create this kind of speakeasy/underground vibe. We filmed at this really cool cabaret jazz club called The Beehive in Boston. I posted on Facebook: “Anyone have a plot of land we can have a bonfire and shoot a film at?” And this guy wrote back that he had big stack of wood in a parking lot. I didn't think that was the aesthetic we were looking for, but it turned out this guy books the talent at The Beehive. So we thought we'd ask him to shoot the speakeasy sound underground with the moon and he said, no problem. Come on in.

So you conceived of the kinds of settings you wanted and then went looking for them.

Exactly. And then for a lot of the indoor dance scenes we were all just kind of cutting through the darkness look of these kind of luminous settings, the gold and red sheer, and then the blackout space.

It's an alluring video. I’ve watched it a few times.

It's definitely a little abstract, but we've been getting a cool response.

You mentioned the violin player and the drummer in the band. Tell me about the others.

There are four of us as the core band. All are great singers and instrumentalists. So that's been really fun to be able to explore harmony singing and layering vocals and things like this. Rob Flax grew up in Chicago. He got his masters here at NEC [New England Conservatory of Music]. He’s a multi-instrumentalist who plays violin and synthesizer in the band and sings. And then we've got Zamar Odongo who plays drums and also sings as well. And then Krista Speroni playing bass and singing.

Billy Wylder is really a family of musicians. It's not a locked-in lineup. But those are the artists who are the core and the ones on this new recording. I like to stay creatively fluid. Sometimes that means playing with other people as songs or projects create themselves. I like to be able to be productive even if that core band is not available. So it's been cool to have a little fluidity to the lineup in the project.

I imagine you're keen to get back on stages soon.

Yes. I got my first Covid shot a week ago. I'm very grateful for that. Also, I want to thank you for sharing all this amazing music with the world. Your lens on the diaspora of African music is really cool.

Nice to connect with you as well. We need to jam together some day.

Sounds like a plan.