Blog May 5, 2015

Tuareg Purple Rain: An Interview with Chris Kirkley

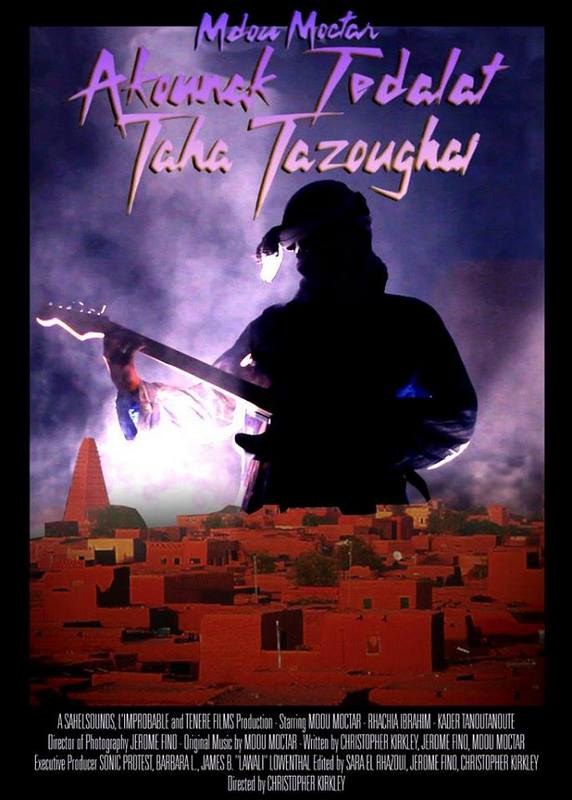

Chris Kirkley of Sahel Sounds took on the epic task of remaking Prince's classic film, Purple Rain, in Agadez, Niger. Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai (“Rain the Color Blue With A Little Red in It”) is the first fiction film ever made in the Tamasheq language, and it's playing in New York this weekend at Anthology Film Archives, along with the original Purple Rain. Chris sat down with Afropop to talk about cross-cultural exchange, telling stories, and making movies.

Sam Backer: Can you tell me a little bit about what the production was like?

Chris Kirkley: You know, I could say it was a nightmare but I was expecting it to be that. So we showed up in Niamey, had a few days to sort of adjust, and then went up to Agadez. We didn't have any pre-production started, so we had to just start doing stuff pretty much when I got there. We had a house rented, so that was the one thing that we did have on our side. We had a nice, big house where we could work in peace, for looking at dailies and what not. We immediately just had our team together and started crossing things off the list, which at that point still included casting.

I think we only had maybe two days to plan our production schedule, gather all the equipment and materials and props, and cast everyone, and we actually started shooting then, right away, with the available actors we had. When we started shooting, we still didn't even have the Apollonia of Purple Rain, the love interest. She wasn't cast yet. We didn't have a purple motorcycle yet, so there are certain scenes where Mdou is just for some reason walking around Agadez.

You actually had to walk around Agadez looking for a purple motorcycle?

Well, we got a motorcycle. When I showed up, there was actually a really nice motorcycle and it was really a unique one. It looked a lot like the motorcycle in Purple Rain, but it didn't run. So I was trying to repair it every day. I kept putting money into the motorcycle and then it would be a different problem, and then a different problem, so eventually we abandoned it.

We ended up getting like the cheapest motorcycle that we could find. I'm not really sure why because we had money budgeted for it but I think everyone was interested in trying to do it on the cheap. So it was a smoky motorcycle--we knew we were going to have to dub in a lot more of a powerful engine cause it really sounded bad. We can't have our hero riding on this thing, you know?

And had you written a script?

Yeah, the script was written and it was in a script format, so the dialogue was largely improvised. On every scene, I was able to give an idea of what was going to be said and then we let the actors improvise because we don't speak Tamasheq and then recently we've had that translated back into English. So that's been kind of a surprise to see what actually was said.

Was anything said that didn't exactly line up?

Yeah, definitely. I've had to do some creative sound editing. Since we were shooting out of sequence, sometimes it wasn't really clear to the actors where that scene would fall in the movie. I think that the main people who were involved knew, but we had some bit parts where people just showed up for a day and we said, "We're going to shoot all your scenes today." So they didn't really understand the order of the film, or really what the film was. Again, that's something that happens when you don't have a lot of pre-production time.

And had you written a script?

Yeah, the script was written and it was in a script format, so the dialogue was largely improvised. On every scene, I was able to give an idea of what was going to be said and then we let the actors improvise because we don't speak Tamasheq and then recently we've had that translated back into English. So that's been kind of a surprise to see what actually was said.

Was anything said that didn't exactly line up?

Yeah, definitely. I've had to do some creative sound editing. Since we were shooting out of sequence, sometimes it wasn't really clear to the actors where that scene would fall in the movie. I think that the main people who were involved knew, but we had some bit parts where people just showed up for a day and we said, "We're going to shoot all your scenes today." So they didn't really understand the order of the film, or really what the film was. Again, that's something that happens when you don't have a lot of pre-production time.

Yeah. Also something that doesn't sound unlike all of Purple Rain, the Prince version.

Yeah. Nothing matches up perfectly. But then we had some surprises too. There were some really great lines that I didn't know I had until it was translated back into a language I could understand and I thought, "Man, this actually really good," you know? Some of the colloquialisms or local phrases that have really beautiful literal translations. Like at one point, I think, Mdou says to his rival that he's accused of being afraid, "God knows I'm not afraid, the lion never gets afraid." And that was a very improv line but I like the imagery in that.

So you had two days pre-production, and then you just jumped right into filming?

Yeah, we did. And we cast the actress. I think we went through three actresses during the film. We had to change a couple of times. I think our first actress, she ended up moving away to Libya. Our second actress, I was actually in the car with them...

Wait, during the production she went to Libya?

Right before we came. She had been cast before on our last trip and then we came back and she was gone. She had moved to Libya. And then we found a second actress and I explained the script to her and we were driving her and her friend back to her house, and suddenly we had this pursuit. We had this Land Cruiser chasing us. When we stopped the car, it pulled up in front of the car and I recognized the guy. He was a Libyan smuggler that I had met on the last trip but he looked a little agitated. I guess that actress that we were trying to cast was his girlfriend and so he would have no part in that. After he had a chance to talk to her, she called and said, "Oh, you know, I don't think I can do the movie." So that was our second actress.

But luckily we found a third and she was amazing. She came via someone who knew about the film in Agadez through Facebook and introduced her to us. He just actually came to our house and said, "Here we go, she wants to be in your movie. So."

I know that when we talked before, you were playing with a lot of really interesting ideas about who was controlling the making of this movie, and who this movie was for, and I know you did a blog post on Sahel Sounds saying that it didn't quite always work out the way you wanted, necessarily.

Right.

I'm wondering, how much control did the actors and the local participants have in the shaping of the movie?

Yeah, it's hard to say. The original concept, obviously, we wrote that together. When it came to shooting, there was a lot of stuff during production that was vetoed. For example, Mdou's guitar is burned in the movie and I wanted it to be because he has an evil marabout cast a spell on him. Because that's something that happens a lot in Agadez, that sort of black magic, and I thought, "Well, this is a good point to reference this because people are talking about black magic all the time." But when I suggested that the character say that, nobody would touch that line. They said, "No, we're not going to say that. On film? My character's gonna say that? No." Also, for our romantic interest between Mdou and Ghaicha--his girlfriend, you could say, in the film--there's no actually physical touching at all. We couldn't even get a hug to happen during the movie. So a lot is left to the imagination.

Yeah. Also something that doesn't sound unlike all of Purple Rain, the Prince version.

Yeah. Nothing matches up perfectly. But then we had some surprises too. There were some really great lines that I didn't know I had until it was translated back into a language I could understand and I thought, "Man, this actually really good," you know? Some of the colloquialisms or local phrases that have really beautiful literal translations. Like at one point, I think, Mdou says to his rival that he's accused of being afraid, "God knows I'm not afraid, the lion never gets afraid." And that was a very improv line but I like the imagery in that.

So you had two days pre-production, and then you just jumped right into filming?

Yeah, we did. And we cast the actress. I think we went through three actresses during the film. We had to change a couple of times. I think our first actress, she ended up moving away to Libya. Our second actress, I was actually in the car with them...

Wait, during the production she went to Libya?

Right before we came. She had been cast before on our last trip and then we came back and she was gone. She had moved to Libya. And then we found a second actress and I explained the script to her and we were driving her and her friend back to her house, and suddenly we had this pursuit. We had this Land Cruiser chasing us. When we stopped the car, it pulled up in front of the car and I recognized the guy. He was a Libyan smuggler that I had met on the last trip but he looked a little agitated. I guess that actress that we were trying to cast was his girlfriend and so he would have no part in that. After he had a chance to talk to her, she called and said, "Oh, you know, I don't think I can do the movie." So that was our second actress.

But luckily we found a third and she was amazing. She came via someone who knew about the film in Agadez through Facebook and introduced her to us. He just actually came to our house and said, "Here we go, she wants to be in your movie. So."

I know that when we talked before, you were playing with a lot of really interesting ideas about who was controlling the making of this movie, and who this movie was for, and I know you did a blog post on Sahel Sounds saying that it didn't quite always work out the way you wanted, necessarily.

Right.

I'm wondering, how much control did the actors and the local participants have in the shaping of the movie?

Yeah, it's hard to say. The original concept, obviously, we wrote that together. When it came to shooting, there was a lot of stuff during production that was vetoed. For example, Mdou's guitar is burned in the movie and I wanted it to be because he has an evil marabout cast a spell on him. Because that's something that happens a lot in Agadez, that sort of black magic, and I thought, "Well, this is a good point to reference this because people are talking about black magic all the time." But when I suggested that the character say that, nobody would touch that line. They said, "No, we're not going to say that. On film? My character's gonna say that? No." Also, for our romantic interest between Mdou and Ghaicha--his girlfriend, you could say, in the film--there's no actually physical touching at all. We couldn't even get a hug to happen during the movie. So a lot is left to the imagination.

They just said they wouldn't hug on film?

Yeah. Well, I think Mdou was OK with it but Ghaicha wasn't having that. So there were these issues. But you know, I talked about having them shape the movie but I think that the biggest difficulty was that we were actually too close to reality with the story line. The story being that Mdou plays a guitarist from a different town who moves to Agadez. There's competition with the old guitarist who feels threatened by Mdou arriving and trying to take over. Mdou has a conflict with his group where he wants to be the star and doesn't want to play their music and only wants to play his music. And all these things are a little too close to reality. Kader and Mdou, in a way, sort of are rivals. And as we were shooting the movie, about halfway through, Kader kind of became absent. He wouldn't show up to the shoots any more. So there are some scenes that are supposed to have Kader in them that don't, because he just stopped answering his phone and he left to travel. And you know, we got the feeling that he was not interested in the movie because he was interpreting it or his friends were talking about how this was something for Mdou. It was gonna put Mdou on the international stage. It was gonna be a movie about him, and it wouldn't help Kader. It would make him look bad. And so we were getting a little too close to reality.

I also expected we'd have an open door thing where we'd showcase a lot of musicians in the film, different musical sequences with just different guitarists. And actually nobody came to the shoots. None of the guitarists who I invited to the different scenes to play in the mock weddings we staged came to play. And it was only after we finished shooting that I was approached by a couple of them saying, "OK, now do you want to make a movie about me?" So that was a little frustrating but also reassuring, because I think we hit on some realities. And I think the film will be actually really relevant in that sense.

You think it'll be relevant to the audience that it's intended for, which is the people there, right?

Yeah, I mean, even the translator I've been working with on it--I'd show him a scene, he'd translate it, and he'd be like, "This is exactly what happens in Niger, this is the problem." So you know, hearing that type of thing was really reassuring to me. And he's actually coming over tonight to watch the film, so it'll be nice to screen it for him, and we're also going to have a chance during this upcoming tour to screen it for Mdou and the band and have their feedback. They can veto stuff. If they want to cut stuff out of it or they think something isn't right, we can change it. And that's really important. It's sort of happenstance, because of our tour, but we're in a really lucky position to have them involved in the post-production. 'Cause I feel like post-production often is like, "I'm gonna go record this band," or even in my case, "I'm gonna record this music and then I'm the one who packages it and edits it and then puts it out." But in this case, we really are gonna have an active role for Mdou to choose how the final film looks.

They just said they wouldn't hug on film?

Yeah. Well, I think Mdou was OK with it but Ghaicha wasn't having that. So there were these issues. But you know, I talked about having them shape the movie but I think that the biggest difficulty was that we were actually too close to reality with the story line. The story being that Mdou plays a guitarist from a different town who moves to Agadez. There's competition with the old guitarist who feels threatened by Mdou arriving and trying to take over. Mdou has a conflict with his group where he wants to be the star and doesn't want to play their music and only wants to play his music. And all these things are a little too close to reality. Kader and Mdou, in a way, sort of are rivals. And as we were shooting the movie, about halfway through, Kader kind of became absent. He wouldn't show up to the shoots any more. So there are some scenes that are supposed to have Kader in them that don't, because he just stopped answering his phone and he left to travel. And you know, we got the feeling that he was not interested in the movie because he was interpreting it or his friends were talking about how this was something for Mdou. It was gonna put Mdou on the international stage. It was gonna be a movie about him, and it wouldn't help Kader. It would make him look bad. And so we were getting a little too close to reality.

I also expected we'd have an open door thing where we'd showcase a lot of musicians in the film, different musical sequences with just different guitarists. And actually nobody came to the shoots. None of the guitarists who I invited to the different scenes to play in the mock weddings we staged came to play. And it was only after we finished shooting that I was approached by a couple of them saying, "OK, now do you want to make a movie about me?" So that was a little frustrating but also reassuring, because I think we hit on some realities. And I think the film will be actually really relevant in that sense.

You think it'll be relevant to the audience that it's intended for, which is the people there, right?

Yeah, I mean, even the translator I've been working with on it--I'd show him a scene, he'd translate it, and he'd be like, "This is exactly what happens in Niger, this is the problem." So you know, hearing that type of thing was really reassuring to me. And he's actually coming over tonight to watch the film, so it'll be nice to screen it for him, and we're also going to have a chance during this upcoming tour to screen it for Mdou and the band and have their feedback. They can veto stuff. If they want to cut stuff out of it or they think something isn't right, we can change it. And that's really important. It's sort of happenstance, because of our tour, but we're in a really lucky position to have them involved in the post-production. 'Cause I feel like post-production often is like, "I'm gonna go record this band," or even in my case, "I'm gonna record this music and then I'm the one who packages it and edits it and then puts it out." But in this case, we really are gonna have an active role for Mdou to choose how the final film looks.

So are you worried that it may still be too close to life? Were people enthusiastic about having that story told?

You know, I think that it's an interesting story. I think they were enthusiastic, Mdou was enthusiastic about that story. But it was almost too hard to have these characters play themselves. Initially, I tried to give them fake names but they said, "Oh no, we want to play ourselves," and I said OK. But the problem with how we did this is, it kept it all very real. If the characters are playing their own names, then they're speaking about each other, and how do you separate that fiction? How do you say when someone's talking about another guitarist, about how they don't pay them well? I mean, you're getting into a tough subject--is it fiction? is it non-fiction? So I think that was probably the hardest part about it, that we blurred that line and dealt with sort of a sensitive subject. I think that the musicians are gonna find this interesting in the end, I think that this is gonna resonate with guitarists from Agadez to Kidal. However, I think that if I go do a movie again, I'm just gonna follow some kids around with the camera. Or pick a little less sensitive of a topic.

In that blog post, you said that you'd try to show streets and they'd be like, "No, no, why would you film a dirty street?" Right?

Yeah, there were a lot of shots that we'd try to take that they didn't agree, that our local crew didn't agree with. And I think that has something to do with just cultural things, like I wanted to show some dirty streets and they said, "Well, you gotta show the nice streets." Or I'd want to show a broken-down corner store and they'd take me to the nicest store in Agadez. And that was perplexing to me because I wanted to show the reality, but then reality is such a subjective thing, you know? And I was thinking, if somebody came to Portland and wanted to shoot, what would they see? What does a foreigner see in a place that attracts their attention? And if you're really trying to show, in our case, a real compromise of the director's eye and also a collaborative eye, there's a big difference, I think, between what we notice.

I mean, I've watched Purple Rain a lot recently, especially during the edit and there's very little of Minneapolis in the movie. There's not a lot. And I think that our tendency to like show a lot of, when you're in a foreign place, when you're a foreigner, you shoot a lot, you say: Oh look at the street, it's amazing. Well, to us, a street in Minneapolis might not be that amazing. So that's the kind of stuff that gets edited out. In lieu of an actual story. That sensationalism of the exotic, that's something that is very subjective.

So yeah, I think perhaps, in the end, the movie won't be as interesting to a Western audience but I really don't care. I really want this to be a Tuareg film, as strange as that may sound, being that I'm not Tuareg. But I think that it's more important to that audience. I think they're the ones that are really going to care about it. And hopefully it can sort of jump-start these nascent Tuareg directors who are like, "That movie was terrible, I can make a better film."

Did the filming of the movie make you think about Purple Rain differently?

Oh man. I think that I've spent a lot more time with that movie now. I feel sort of closer to Prince. Like his song came on yesterday in a restaurant and I was like, "Oh yeah, yeah, I'm Prince!" You know, as I've been breaking his movie down and watching it repeatedly, I think I have a little more respect for the movie, in a way. When I went into the project, I sort of thought of it as this kitsch 1980s formulaic movie and I don't really see it like that now. I think I appreciate more of the complexities behind it, that it's a little deeper than that. Part of what makes it kitsch is just that it's dated and that there's some pretty terrible things--at times it's a pretty sexist film. But if we can try to view it in the context of movies that were happening at that time, Prince was trying to tell a story about the struggle of being an artist. And I think that maybe our film can mirror that deeper than I thought it would.

So are you worried that it may still be too close to life? Were people enthusiastic about having that story told?

You know, I think that it's an interesting story. I think they were enthusiastic, Mdou was enthusiastic about that story. But it was almost too hard to have these characters play themselves. Initially, I tried to give them fake names but they said, "Oh no, we want to play ourselves," and I said OK. But the problem with how we did this is, it kept it all very real. If the characters are playing their own names, then they're speaking about each other, and how do you separate that fiction? How do you say when someone's talking about another guitarist, about how they don't pay them well? I mean, you're getting into a tough subject--is it fiction? is it non-fiction? So I think that was probably the hardest part about it, that we blurred that line and dealt with sort of a sensitive subject. I think that the musicians are gonna find this interesting in the end, I think that this is gonna resonate with guitarists from Agadez to Kidal. However, I think that if I go do a movie again, I'm just gonna follow some kids around with the camera. Or pick a little less sensitive of a topic.

In that blog post, you said that you'd try to show streets and they'd be like, "No, no, why would you film a dirty street?" Right?

Yeah, there were a lot of shots that we'd try to take that they didn't agree, that our local crew didn't agree with. And I think that has something to do with just cultural things, like I wanted to show some dirty streets and they said, "Well, you gotta show the nice streets." Or I'd want to show a broken-down corner store and they'd take me to the nicest store in Agadez. And that was perplexing to me because I wanted to show the reality, but then reality is such a subjective thing, you know? And I was thinking, if somebody came to Portland and wanted to shoot, what would they see? What does a foreigner see in a place that attracts their attention? And if you're really trying to show, in our case, a real compromise of the director's eye and also a collaborative eye, there's a big difference, I think, between what we notice.

I mean, I've watched Purple Rain a lot recently, especially during the edit and there's very little of Minneapolis in the movie. There's not a lot. And I think that our tendency to like show a lot of, when you're in a foreign place, when you're a foreigner, you shoot a lot, you say: Oh look at the street, it's amazing. Well, to us, a street in Minneapolis might not be that amazing. So that's the kind of stuff that gets edited out. In lieu of an actual story. That sensationalism of the exotic, that's something that is very subjective.

So yeah, I think perhaps, in the end, the movie won't be as interesting to a Western audience but I really don't care. I really want this to be a Tuareg film, as strange as that may sound, being that I'm not Tuareg. But I think that it's more important to that audience. I think they're the ones that are really going to care about it. And hopefully it can sort of jump-start these nascent Tuareg directors who are like, "That movie was terrible, I can make a better film."

Did the filming of the movie make you think about Purple Rain differently?

Oh man. I think that I've spent a lot more time with that movie now. I feel sort of closer to Prince. Like his song came on yesterday in a restaurant and I was like, "Oh yeah, yeah, I'm Prince!" You know, as I've been breaking his movie down and watching it repeatedly, I think I have a little more respect for the movie, in a way. When I went into the project, I sort of thought of it as this kitsch 1980s formulaic movie and I don't really see it like that now. I think I appreciate more of the complexities behind it, that it's a little deeper than that. Part of what makes it kitsch is just that it's dated and that there's some pretty terrible things--at times it's a pretty sexist film. But if we can try to view it in the context of movies that were happening at that time, Prince was trying to tell a story about the struggle of being an artist. And I think that maybe our film can mirror that deeper than I thought it would.

Yeah. And I also think, from my memories of the movie, it's also about storytelling, and kind of mythologizing--it's this act of crazy self-mythologizing but also kind of rad. But the narrative--it's not super strong through the whole movie. He's not a guitar god.

Right, he's a flawed character too. He makes a lot of mistakes. I think one difference between that and our movie is, maybe, that self-mythology, that self-aggrandizing feature, is really characteristic of Prince and our movie's a lot more subdued. There were certain times where I was like, "Mdou, fly off the handle!" and he's like, "No, why would I do that? That's not how people talk here."

For example, when his father burns his guitar: If you remember the conflict in Purple Rain between Prince and his father, it's a really intense conflict between them. And in our adaptation of it, his father burns his guitar--and it's the only guitar Mdou has--and when he comes out and talks to him, he's not yelling at his father. And I said, "Mdou, no, you have to really come out angry. You have to yell." He said, "Nobody yells at their father here." In Tuareg society, you don't yell at your father. You can be mad but you can't show it to that extent. And when I showed the movie to some friends the other night, they were like, "He doesn't seem like he's angry enough." And I said, "Well, then maybe this movie's not for you. So maybe we nailed it." And that is something we're going to deal with when different audiences watch the movie, but I'm glad that we kept it more true to form of what people there are gonna want and expect.

I also think it's an interesting move because, in a weird way, record producing is always storytelling, especially with music from other parts of the world, but I think it's really interesting to make that more explicit.

Yeah. Well, I think part of what fascinated me about working on this project is basically an extension of that. I have to constantly remind myself that I didn't get into this business to produce records. What's always interested me is looking at the cultural artifacts and examining them, and the only thing that the label has really provided is that now I'm telling it. I'm taking this thing and telling it to Westerners. So it's been really interesting to work on something that can sort of straddle both worlds and just play around with it, you know?

Whether or not it's successful, it's definitely been a really fascinating project and I think all of us have learned a lot from it. Not just myself, Jerome, and Sarah, but also Mdou, Moustapha, who worked on the film, Mdou's brother, who was a big part of our team as well, and all of the cast who were involved. It was a very intense learning experience about how we worked together. And how to make a movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHgEuzv-zNA

Do you think you're going to make more films?

Well, I've been joking that I should just start a production remaking 1980s movies in West Africa, like we do Police Academy--

Die Hard cuts a little bit too close, I think.

Yeah, right. But yeah, I'd like to work on another film. I've got a lot of projects that I'd like to work on. I'm really interested in doing something with the director over there for a next project, so somebody who already is shooting films and can find actors. Cause there's a lot of good actors. I mean, even in Agadez, we found actors. We didn't know about them but once we were there, we found a couple professional comedians and they were amazing and I thought, man, who would have known about these people before? So I'd like to work more with people there.

There's an Agadez comedy circuit?

There's an Agadez comedy troupe--it's like these two guys who run this school and they teach kids how to be actors and comedians.

That's a movie.

Yeah, I mean, they're hilarious. It was great to see. 'Cause if you go to a place where acting isn't a big part of the culture, it's hard to find actors. I mean, everyone's exposed to films so people know what fiction is, but, you know. I think a lot of us have been in at least a few plays as kids, so we kind of grow up with it, for better or worse.

I also want to tell you that one of the most interesting final stages of this project is that I have a contact in Nigeria who works in the film industry so we're going to get like 5000 DVDs made and I'm going to get them distributed across the Tuareg diaspora. You know, send 1000 up to Agadez, 1000 to northern Mali, I'm gonna send some to Libya, some to Algeria. We're not really looking to recoup any of the costs of the DVDs so we're just going try to drop these into different places. So that'll be kind of the conclusion of the project, I think. After the premiers and everything, that will be that final step. So I'm really interested to see what will happen after that.

You mean after all this time of tracking cassette tapes, your finally tagging things and letting them back out?

Yeah. Will this movie be received everywhere? Will people be watching it all over? Will Mdou become a star in West Africa? I don't know. I don't know what's going to happen, but I like the idea of somebody coming to Tripoli or something in 15 years and finding this Nigerian DVD copy of this movie, you know? So we'll see.

Yeah, that's amazing. I really like that. So it sounds like it was kind of crazy but successful.

You know, when I look at it I'm like, "Wow, the fact that we got enough footage and we edited it and you can follow it, and it tells a story--I'm impressed that we did that." 'Cause just shooting something over that short a period, that was pretty hectic.

Yeah. And I also think, from my memories of the movie, it's also about storytelling, and kind of mythologizing--it's this act of crazy self-mythologizing but also kind of rad. But the narrative--it's not super strong through the whole movie. He's not a guitar god.

Right, he's a flawed character too. He makes a lot of mistakes. I think one difference between that and our movie is, maybe, that self-mythology, that self-aggrandizing feature, is really characteristic of Prince and our movie's a lot more subdued. There were certain times where I was like, "Mdou, fly off the handle!" and he's like, "No, why would I do that? That's not how people talk here."

For example, when his father burns his guitar: If you remember the conflict in Purple Rain between Prince and his father, it's a really intense conflict between them. And in our adaptation of it, his father burns his guitar--and it's the only guitar Mdou has--and when he comes out and talks to him, he's not yelling at his father. And I said, "Mdou, no, you have to really come out angry. You have to yell." He said, "Nobody yells at their father here." In Tuareg society, you don't yell at your father. You can be mad but you can't show it to that extent. And when I showed the movie to some friends the other night, they were like, "He doesn't seem like he's angry enough." And I said, "Well, then maybe this movie's not for you. So maybe we nailed it." And that is something we're going to deal with when different audiences watch the movie, but I'm glad that we kept it more true to form of what people there are gonna want and expect.

I also think it's an interesting move because, in a weird way, record producing is always storytelling, especially with music from other parts of the world, but I think it's really interesting to make that more explicit.

Yeah. Well, I think part of what fascinated me about working on this project is basically an extension of that. I have to constantly remind myself that I didn't get into this business to produce records. What's always interested me is looking at the cultural artifacts and examining them, and the only thing that the label has really provided is that now I'm telling it. I'm taking this thing and telling it to Westerners. So it's been really interesting to work on something that can sort of straddle both worlds and just play around with it, you know?

Whether or not it's successful, it's definitely been a really fascinating project and I think all of us have learned a lot from it. Not just myself, Jerome, and Sarah, but also Mdou, Moustapha, who worked on the film, Mdou's brother, who was a big part of our team as well, and all of the cast who were involved. It was a very intense learning experience about how we worked together. And how to make a movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHgEuzv-zNA

Do you think you're going to make more films?

Well, I've been joking that I should just start a production remaking 1980s movies in West Africa, like we do Police Academy--

Die Hard cuts a little bit too close, I think.

Yeah, right. But yeah, I'd like to work on another film. I've got a lot of projects that I'd like to work on. I'm really interested in doing something with the director over there for a next project, so somebody who already is shooting films and can find actors. Cause there's a lot of good actors. I mean, even in Agadez, we found actors. We didn't know about them but once we were there, we found a couple professional comedians and they were amazing and I thought, man, who would have known about these people before? So I'd like to work more with people there.

There's an Agadez comedy circuit?

There's an Agadez comedy troupe--it's like these two guys who run this school and they teach kids how to be actors and comedians.

That's a movie.

Yeah, I mean, they're hilarious. It was great to see. 'Cause if you go to a place where acting isn't a big part of the culture, it's hard to find actors. I mean, everyone's exposed to films so people know what fiction is, but, you know. I think a lot of us have been in at least a few plays as kids, so we kind of grow up with it, for better or worse.

I also want to tell you that one of the most interesting final stages of this project is that I have a contact in Nigeria who works in the film industry so we're going to get like 5000 DVDs made and I'm going to get them distributed across the Tuareg diaspora. You know, send 1000 up to Agadez, 1000 to northern Mali, I'm gonna send some to Libya, some to Algeria. We're not really looking to recoup any of the costs of the DVDs so we're just going try to drop these into different places. So that'll be kind of the conclusion of the project, I think. After the premiers and everything, that will be that final step. So I'm really interested to see what will happen after that.

You mean after all this time of tracking cassette tapes, your finally tagging things and letting them back out?

Yeah. Will this movie be received everywhere? Will people be watching it all over? Will Mdou become a star in West Africa? I don't know. I don't know what's going to happen, but I like the idea of somebody coming to Tripoli or something in 15 years and finding this Nigerian DVD copy of this movie, you know? So we'll see.

Yeah, that's amazing. I really like that. So it sounds like it was kind of crazy but successful.

You know, when I look at it I'm like, "Wow, the fact that we got enough footage and we edited it and you can follow it, and it tells a story--I'm impressed that we did that." 'Cause just shooting something over that short a period, that was pretty hectic.

The making-of movie would have been a more interesting movie than the movie. To the Western audience at least. Maybe even to the Tuareg audience. But unfortunately, we shot some footage of the making-of, we had a second camera man, but we were so short staffed that we just pulled him to shoot the actual movie, you know? "Hold this boom pole ..."

Well, we got a film made, which I think we probably shouldn't have.

The making-of movie would have been a more interesting movie than the movie. To the Western audience at least. Maybe even to the Tuareg audience. But unfortunately, we shot some footage of the making-of, we had a second camera man, but we were so short staffed that we just pulled him to shoot the actual movie, you know? "Hold this boom pole ..."

Well, we got a film made, which I think we probably shouldn't have.

And had you written a script?

Yeah, the script was written and it was in a script format, so the dialogue was largely improvised. On every scene, I was able to give an idea of what was going to be said and then we let the actors improvise because we don't speak Tamasheq and then recently we've had that translated back into English. So that's been kind of a surprise to see what actually was said.

Was anything said that didn't exactly line up?

Yeah, definitely. I've had to do some creative sound editing. Since we were shooting out of sequence, sometimes it wasn't really clear to the actors where that scene would fall in the movie. I think that the main people who were involved knew, but we had some bit parts where people just showed up for a day and we said, "We're going to shoot all your scenes today." So they didn't really understand the order of the film, or really what the film was. Again, that's something that happens when you don't have a lot of pre-production time.

And had you written a script?

Yeah, the script was written and it was in a script format, so the dialogue was largely improvised. On every scene, I was able to give an idea of what was going to be said and then we let the actors improvise because we don't speak Tamasheq and then recently we've had that translated back into English. So that's been kind of a surprise to see what actually was said.

Was anything said that didn't exactly line up?

Yeah, definitely. I've had to do some creative sound editing. Since we were shooting out of sequence, sometimes it wasn't really clear to the actors where that scene would fall in the movie. I think that the main people who were involved knew, but we had some bit parts where people just showed up for a day and we said, "We're going to shoot all your scenes today." So they didn't really understand the order of the film, or really what the film was. Again, that's something that happens when you don't have a lot of pre-production time.

Yeah. Also something that doesn't sound unlike all of Purple Rain, the Prince version.

Yeah. Nothing matches up perfectly. But then we had some surprises too. There were some really great lines that I didn't know I had until it was translated back into a language I could understand and I thought, "Man, this actually really good," you know? Some of the colloquialisms or local phrases that have really beautiful literal translations. Like at one point, I think, Mdou says to his rival that he's accused of being afraid, "God knows I'm not afraid, the lion never gets afraid." And that was a very improv line but I like the imagery in that.

So you had two days pre-production, and then you just jumped right into filming?

Yeah, we did. And we cast the actress. I think we went through three actresses during the film. We had to change a couple of times. I think our first actress, she ended up moving away to Libya. Our second actress, I was actually in the car with them...

Wait, during the production she went to Libya?

Right before we came. She had been cast before on our last trip and then we came back and she was gone. She had moved to Libya. And then we found a second actress and I explained the script to her and we were driving her and her friend back to her house, and suddenly we had this pursuit. We had this Land Cruiser chasing us. When we stopped the car, it pulled up in front of the car and I recognized the guy. He was a Libyan smuggler that I had met on the last trip but he looked a little agitated. I guess that actress that we were trying to cast was his girlfriend and so he would have no part in that. After he had a chance to talk to her, she called and said, "Oh, you know, I don't think I can do the movie." So that was our second actress.

But luckily we found a third and she was amazing. She came via someone who knew about the film in Agadez through Facebook and introduced her to us. He just actually came to our house and said, "Here we go, she wants to be in your movie. So."

I know that when we talked before, you were playing with a lot of really interesting ideas about who was controlling the making of this movie, and who this movie was for, and I know you did a blog post on Sahel Sounds saying that it didn't quite always work out the way you wanted, necessarily.

Right.

I'm wondering, how much control did the actors and the local participants have in the shaping of the movie?

Yeah, it's hard to say. The original concept, obviously, we wrote that together. When it came to shooting, there was a lot of stuff during production that was vetoed. For example, Mdou's guitar is burned in the movie and I wanted it to be because he has an evil marabout cast a spell on him. Because that's something that happens a lot in Agadez, that sort of black magic, and I thought, "Well, this is a good point to reference this because people are talking about black magic all the time." But when I suggested that the character say that, nobody would touch that line. They said, "No, we're not going to say that. On film? My character's gonna say that? No." Also, for our romantic interest between Mdou and Ghaicha--his girlfriend, you could say, in the film--there's no actually physical touching at all. We couldn't even get a hug to happen during the movie. So a lot is left to the imagination.

Yeah. Also something that doesn't sound unlike all of Purple Rain, the Prince version.

Yeah. Nothing matches up perfectly. But then we had some surprises too. There were some really great lines that I didn't know I had until it was translated back into a language I could understand and I thought, "Man, this actually really good," you know? Some of the colloquialisms or local phrases that have really beautiful literal translations. Like at one point, I think, Mdou says to his rival that he's accused of being afraid, "God knows I'm not afraid, the lion never gets afraid." And that was a very improv line but I like the imagery in that.

So you had two days pre-production, and then you just jumped right into filming?

Yeah, we did. And we cast the actress. I think we went through three actresses during the film. We had to change a couple of times. I think our first actress, she ended up moving away to Libya. Our second actress, I was actually in the car with them...

Wait, during the production she went to Libya?

Right before we came. She had been cast before on our last trip and then we came back and she was gone. She had moved to Libya. And then we found a second actress and I explained the script to her and we were driving her and her friend back to her house, and suddenly we had this pursuit. We had this Land Cruiser chasing us. When we stopped the car, it pulled up in front of the car and I recognized the guy. He was a Libyan smuggler that I had met on the last trip but he looked a little agitated. I guess that actress that we were trying to cast was his girlfriend and so he would have no part in that. After he had a chance to talk to her, she called and said, "Oh, you know, I don't think I can do the movie." So that was our second actress.

But luckily we found a third and she was amazing. She came via someone who knew about the film in Agadez through Facebook and introduced her to us. He just actually came to our house and said, "Here we go, she wants to be in your movie. So."

I know that when we talked before, you were playing with a lot of really interesting ideas about who was controlling the making of this movie, and who this movie was for, and I know you did a blog post on Sahel Sounds saying that it didn't quite always work out the way you wanted, necessarily.

Right.

I'm wondering, how much control did the actors and the local participants have in the shaping of the movie?

Yeah, it's hard to say. The original concept, obviously, we wrote that together. When it came to shooting, there was a lot of stuff during production that was vetoed. For example, Mdou's guitar is burned in the movie and I wanted it to be because he has an evil marabout cast a spell on him. Because that's something that happens a lot in Agadez, that sort of black magic, and I thought, "Well, this is a good point to reference this because people are talking about black magic all the time." But when I suggested that the character say that, nobody would touch that line. They said, "No, we're not going to say that. On film? My character's gonna say that? No." Also, for our romantic interest between Mdou and Ghaicha--his girlfriend, you could say, in the film--there's no actually physical touching at all. We couldn't even get a hug to happen during the movie. So a lot is left to the imagination.

They just said they wouldn't hug on film?

Yeah. Well, I think Mdou was OK with it but Ghaicha wasn't having that. So there were these issues. But you know, I talked about having them shape the movie but I think that the biggest difficulty was that we were actually too close to reality with the story line. The story being that Mdou plays a guitarist from a different town who moves to Agadez. There's competition with the old guitarist who feels threatened by Mdou arriving and trying to take over. Mdou has a conflict with his group where he wants to be the star and doesn't want to play their music and only wants to play his music. And all these things are a little too close to reality. Kader and Mdou, in a way, sort of are rivals. And as we were shooting the movie, about halfway through, Kader kind of became absent. He wouldn't show up to the shoots any more. So there are some scenes that are supposed to have Kader in them that don't, because he just stopped answering his phone and he left to travel. And you know, we got the feeling that he was not interested in the movie because he was interpreting it or his friends were talking about how this was something for Mdou. It was gonna put Mdou on the international stage. It was gonna be a movie about him, and it wouldn't help Kader. It would make him look bad. And so we were getting a little too close to reality.

I also expected we'd have an open door thing where we'd showcase a lot of musicians in the film, different musical sequences with just different guitarists. And actually nobody came to the shoots. None of the guitarists who I invited to the different scenes to play in the mock weddings we staged came to play. And it was only after we finished shooting that I was approached by a couple of them saying, "OK, now do you want to make a movie about me?" So that was a little frustrating but also reassuring, because I think we hit on some realities. And I think the film will be actually really relevant in that sense.

You think it'll be relevant to the audience that it's intended for, which is the people there, right?

Yeah, I mean, even the translator I've been working with on it--I'd show him a scene, he'd translate it, and he'd be like, "This is exactly what happens in Niger, this is the problem." So you know, hearing that type of thing was really reassuring to me. And he's actually coming over tonight to watch the film, so it'll be nice to screen it for him, and we're also going to have a chance during this upcoming tour to screen it for Mdou and the band and have their feedback. They can veto stuff. If they want to cut stuff out of it or they think something isn't right, we can change it. And that's really important. It's sort of happenstance, because of our tour, but we're in a really lucky position to have them involved in the post-production. 'Cause I feel like post-production often is like, "I'm gonna go record this band," or even in my case, "I'm gonna record this music and then I'm the one who packages it and edits it and then puts it out." But in this case, we really are gonna have an active role for Mdou to choose how the final film looks.

They just said they wouldn't hug on film?

Yeah. Well, I think Mdou was OK with it but Ghaicha wasn't having that. So there were these issues. But you know, I talked about having them shape the movie but I think that the biggest difficulty was that we were actually too close to reality with the story line. The story being that Mdou plays a guitarist from a different town who moves to Agadez. There's competition with the old guitarist who feels threatened by Mdou arriving and trying to take over. Mdou has a conflict with his group where he wants to be the star and doesn't want to play their music and only wants to play his music. And all these things are a little too close to reality. Kader and Mdou, in a way, sort of are rivals. And as we were shooting the movie, about halfway through, Kader kind of became absent. He wouldn't show up to the shoots any more. So there are some scenes that are supposed to have Kader in them that don't, because he just stopped answering his phone and he left to travel. And you know, we got the feeling that he was not interested in the movie because he was interpreting it or his friends were talking about how this was something for Mdou. It was gonna put Mdou on the international stage. It was gonna be a movie about him, and it wouldn't help Kader. It would make him look bad. And so we were getting a little too close to reality.

I also expected we'd have an open door thing where we'd showcase a lot of musicians in the film, different musical sequences with just different guitarists. And actually nobody came to the shoots. None of the guitarists who I invited to the different scenes to play in the mock weddings we staged came to play. And it was only after we finished shooting that I was approached by a couple of them saying, "OK, now do you want to make a movie about me?" So that was a little frustrating but also reassuring, because I think we hit on some realities. And I think the film will be actually really relevant in that sense.

You think it'll be relevant to the audience that it's intended for, which is the people there, right?

Yeah, I mean, even the translator I've been working with on it--I'd show him a scene, he'd translate it, and he'd be like, "This is exactly what happens in Niger, this is the problem." So you know, hearing that type of thing was really reassuring to me. And he's actually coming over tonight to watch the film, so it'll be nice to screen it for him, and we're also going to have a chance during this upcoming tour to screen it for Mdou and the band and have their feedback. They can veto stuff. If they want to cut stuff out of it or they think something isn't right, we can change it. And that's really important. It's sort of happenstance, because of our tour, but we're in a really lucky position to have them involved in the post-production. 'Cause I feel like post-production often is like, "I'm gonna go record this band," or even in my case, "I'm gonna record this music and then I'm the one who packages it and edits it and then puts it out." But in this case, we really are gonna have an active role for Mdou to choose how the final film looks.

So are you worried that it may still be too close to life? Were people enthusiastic about having that story told?

You know, I think that it's an interesting story. I think they were enthusiastic, Mdou was enthusiastic about that story. But it was almost too hard to have these characters play themselves. Initially, I tried to give them fake names but they said, "Oh no, we want to play ourselves," and I said OK. But the problem with how we did this is, it kept it all very real. If the characters are playing their own names, then they're speaking about each other, and how do you separate that fiction? How do you say when someone's talking about another guitarist, about how they don't pay them well? I mean, you're getting into a tough subject--is it fiction? is it non-fiction? So I think that was probably the hardest part about it, that we blurred that line and dealt with sort of a sensitive subject. I think that the musicians are gonna find this interesting in the end, I think that this is gonna resonate with guitarists from Agadez to Kidal. However, I think that if I go do a movie again, I'm just gonna follow some kids around with the camera. Or pick a little less sensitive of a topic.

In that blog post, you said that you'd try to show streets and they'd be like, "No, no, why would you film a dirty street?" Right?

Yeah, there were a lot of shots that we'd try to take that they didn't agree, that our local crew didn't agree with. And I think that has something to do with just cultural things, like I wanted to show some dirty streets and they said, "Well, you gotta show the nice streets." Or I'd want to show a broken-down corner store and they'd take me to the nicest store in Agadez. And that was perplexing to me because I wanted to show the reality, but then reality is such a subjective thing, you know? And I was thinking, if somebody came to Portland and wanted to shoot, what would they see? What does a foreigner see in a place that attracts their attention? And if you're really trying to show, in our case, a real compromise of the director's eye and also a collaborative eye, there's a big difference, I think, between what we notice.

I mean, I've watched Purple Rain a lot recently, especially during the edit and there's very little of Minneapolis in the movie. There's not a lot. And I think that our tendency to like show a lot of, when you're in a foreign place, when you're a foreigner, you shoot a lot, you say: Oh look at the street, it's amazing. Well, to us, a street in Minneapolis might not be that amazing. So that's the kind of stuff that gets edited out. In lieu of an actual story. That sensationalism of the exotic, that's something that is very subjective.

So yeah, I think perhaps, in the end, the movie won't be as interesting to a Western audience but I really don't care. I really want this to be a Tuareg film, as strange as that may sound, being that I'm not Tuareg. But I think that it's more important to that audience. I think they're the ones that are really going to care about it. And hopefully it can sort of jump-start these nascent Tuareg directors who are like, "That movie was terrible, I can make a better film."

Did the filming of the movie make you think about Purple Rain differently?

Oh man. I think that I've spent a lot more time with that movie now. I feel sort of closer to Prince. Like his song came on yesterday in a restaurant and I was like, "Oh yeah, yeah, I'm Prince!" You know, as I've been breaking his movie down and watching it repeatedly, I think I have a little more respect for the movie, in a way. When I went into the project, I sort of thought of it as this kitsch 1980s formulaic movie and I don't really see it like that now. I think I appreciate more of the complexities behind it, that it's a little deeper than that. Part of what makes it kitsch is just that it's dated and that there's some pretty terrible things--at times it's a pretty sexist film. But if we can try to view it in the context of movies that were happening at that time, Prince was trying to tell a story about the struggle of being an artist. And I think that maybe our film can mirror that deeper than I thought it would.

So are you worried that it may still be too close to life? Were people enthusiastic about having that story told?

You know, I think that it's an interesting story. I think they were enthusiastic, Mdou was enthusiastic about that story. But it was almost too hard to have these characters play themselves. Initially, I tried to give them fake names but they said, "Oh no, we want to play ourselves," and I said OK. But the problem with how we did this is, it kept it all very real. If the characters are playing their own names, then they're speaking about each other, and how do you separate that fiction? How do you say when someone's talking about another guitarist, about how they don't pay them well? I mean, you're getting into a tough subject--is it fiction? is it non-fiction? So I think that was probably the hardest part about it, that we blurred that line and dealt with sort of a sensitive subject. I think that the musicians are gonna find this interesting in the end, I think that this is gonna resonate with guitarists from Agadez to Kidal. However, I think that if I go do a movie again, I'm just gonna follow some kids around with the camera. Or pick a little less sensitive of a topic.

In that blog post, you said that you'd try to show streets and they'd be like, "No, no, why would you film a dirty street?" Right?

Yeah, there were a lot of shots that we'd try to take that they didn't agree, that our local crew didn't agree with. And I think that has something to do with just cultural things, like I wanted to show some dirty streets and they said, "Well, you gotta show the nice streets." Or I'd want to show a broken-down corner store and they'd take me to the nicest store in Agadez. And that was perplexing to me because I wanted to show the reality, but then reality is such a subjective thing, you know? And I was thinking, if somebody came to Portland and wanted to shoot, what would they see? What does a foreigner see in a place that attracts their attention? And if you're really trying to show, in our case, a real compromise of the director's eye and also a collaborative eye, there's a big difference, I think, between what we notice.

I mean, I've watched Purple Rain a lot recently, especially during the edit and there's very little of Minneapolis in the movie. There's not a lot. And I think that our tendency to like show a lot of, when you're in a foreign place, when you're a foreigner, you shoot a lot, you say: Oh look at the street, it's amazing. Well, to us, a street in Minneapolis might not be that amazing. So that's the kind of stuff that gets edited out. In lieu of an actual story. That sensationalism of the exotic, that's something that is very subjective.

So yeah, I think perhaps, in the end, the movie won't be as interesting to a Western audience but I really don't care. I really want this to be a Tuareg film, as strange as that may sound, being that I'm not Tuareg. But I think that it's more important to that audience. I think they're the ones that are really going to care about it. And hopefully it can sort of jump-start these nascent Tuareg directors who are like, "That movie was terrible, I can make a better film."

Did the filming of the movie make you think about Purple Rain differently?

Oh man. I think that I've spent a lot more time with that movie now. I feel sort of closer to Prince. Like his song came on yesterday in a restaurant and I was like, "Oh yeah, yeah, I'm Prince!" You know, as I've been breaking his movie down and watching it repeatedly, I think I have a little more respect for the movie, in a way. When I went into the project, I sort of thought of it as this kitsch 1980s formulaic movie and I don't really see it like that now. I think I appreciate more of the complexities behind it, that it's a little deeper than that. Part of what makes it kitsch is just that it's dated and that there's some pretty terrible things--at times it's a pretty sexist film. But if we can try to view it in the context of movies that were happening at that time, Prince was trying to tell a story about the struggle of being an artist. And I think that maybe our film can mirror that deeper than I thought it would.

Yeah. And I also think, from my memories of the movie, it's also about storytelling, and kind of mythologizing--it's this act of crazy self-mythologizing but also kind of rad. But the narrative--it's not super strong through the whole movie. He's not a guitar god.

Right, he's a flawed character too. He makes a lot of mistakes. I think one difference between that and our movie is, maybe, that self-mythology, that self-aggrandizing feature, is really characteristic of Prince and our movie's a lot more subdued. There were certain times where I was like, "Mdou, fly off the handle!" and he's like, "No, why would I do that? That's not how people talk here."

For example, when his father burns his guitar: If you remember the conflict in Purple Rain between Prince and his father, it's a really intense conflict between them. And in our adaptation of it, his father burns his guitar--and it's the only guitar Mdou has--and when he comes out and talks to him, he's not yelling at his father. And I said, "Mdou, no, you have to really come out angry. You have to yell." He said, "Nobody yells at their father here." In Tuareg society, you don't yell at your father. You can be mad but you can't show it to that extent. And when I showed the movie to some friends the other night, they were like, "He doesn't seem like he's angry enough." And I said, "Well, then maybe this movie's not for you. So maybe we nailed it." And that is something we're going to deal with when different audiences watch the movie, but I'm glad that we kept it more true to form of what people there are gonna want and expect.

I also think it's an interesting move because, in a weird way, record producing is always storytelling, especially with music from other parts of the world, but I think it's really interesting to make that more explicit.

Yeah. Well, I think part of what fascinated me about working on this project is basically an extension of that. I have to constantly remind myself that I didn't get into this business to produce records. What's always interested me is looking at the cultural artifacts and examining them, and the only thing that the label has really provided is that now I'm telling it. I'm taking this thing and telling it to Westerners. So it's been really interesting to work on something that can sort of straddle both worlds and just play around with it, you know?

Whether or not it's successful, it's definitely been a really fascinating project and I think all of us have learned a lot from it. Not just myself, Jerome, and Sarah, but also Mdou, Moustapha, who worked on the film, Mdou's brother, who was a big part of our team as well, and all of the cast who were involved. It was a very intense learning experience about how we worked together. And how to make a movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHgEuzv-zNA

Do you think you're going to make more films?

Well, I've been joking that I should just start a production remaking 1980s movies in West Africa, like we do Police Academy--

Die Hard cuts a little bit too close, I think.

Yeah, right. But yeah, I'd like to work on another film. I've got a lot of projects that I'd like to work on. I'm really interested in doing something with the director over there for a next project, so somebody who already is shooting films and can find actors. Cause there's a lot of good actors. I mean, even in Agadez, we found actors. We didn't know about them but once we were there, we found a couple professional comedians and they were amazing and I thought, man, who would have known about these people before? So I'd like to work more with people there.

There's an Agadez comedy circuit?

There's an Agadez comedy troupe--it's like these two guys who run this school and they teach kids how to be actors and comedians.

That's a movie.

Yeah, I mean, they're hilarious. It was great to see. 'Cause if you go to a place where acting isn't a big part of the culture, it's hard to find actors. I mean, everyone's exposed to films so people know what fiction is, but, you know. I think a lot of us have been in at least a few plays as kids, so we kind of grow up with it, for better or worse.

I also want to tell you that one of the most interesting final stages of this project is that I have a contact in Nigeria who works in the film industry so we're going to get like 5000 DVDs made and I'm going to get them distributed across the Tuareg diaspora. You know, send 1000 up to Agadez, 1000 to northern Mali, I'm gonna send some to Libya, some to Algeria. We're not really looking to recoup any of the costs of the DVDs so we're just going try to drop these into different places. So that'll be kind of the conclusion of the project, I think. After the premiers and everything, that will be that final step. So I'm really interested to see what will happen after that.

You mean after all this time of tracking cassette tapes, your finally tagging things and letting them back out?

Yeah. Will this movie be received everywhere? Will people be watching it all over? Will Mdou become a star in West Africa? I don't know. I don't know what's going to happen, but I like the idea of somebody coming to Tripoli or something in 15 years and finding this Nigerian DVD copy of this movie, you know? So we'll see.

Yeah, that's amazing. I really like that. So it sounds like it was kind of crazy but successful.

You know, when I look at it I'm like, "Wow, the fact that we got enough footage and we edited it and you can follow it, and it tells a story--I'm impressed that we did that." 'Cause just shooting something over that short a period, that was pretty hectic.

Yeah. And I also think, from my memories of the movie, it's also about storytelling, and kind of mythologizing--it's this act of crazy self-mythologizing but also kind of rad. But the narrative--it's not super strong through the whole movie. He's not a guitar god.

Right, he's a flawed character too. He makes a lot of mistakes. I think one difference between that and our movie is, maybe, that self-mythology, that self-aggrandizing feature, is really characteristic of Prince and our movie's a lot more subdued. There were certain times where I was like, "Mdou, fly off the handle!" and he's like, "No, why would I do that? That's not how people talk here."

For example, when his father burns his guitar: If you remember the conflict in Purple Rain between Prince and his father, it's a really intense conflict between them. And in our adaptation of it, his father burns his guitar--and it's the only guitar Mdou has--and when he comes out and talks to him, he's not yelling at his father. And I said, "Mdou, no, you have to really come out angry. You have to yell." He said, "Nobody yells at their father here." In Tuareg society, you don't yell at your father. You can be mad but you can't show it to that extent. And when I showed the movie to some friends the other night, they were like, "He doesn't seem like he's angry enough." And I said, "Well, then maybe this movie's not for you. So maybe we nailed it." And that is something we're going to deal with when different audiences watch the movie, but I'm glad that we kept it more true to form of what people there are gonna want and expect.

I also think it's an interesting move because, in a weird way, record producing is always storytelling, especially with music from other parts of the world, but I think it's really interesting to make that more explicit.

Yeah. Well, I think part of what fascinated me about working on this project is basically an extension of that. I have to constantly remind myself that I didn't get into this business to produce records. What's always interested me is looking at the cultural artifacts and examining them, and the only thing that the label has really provided is that now I'm telling it. I'm taking this thing and telling it to Westerners. So it's been really interesting to work on something that can sort of straddle both worlds and just play around with it, you know?

Whether or not it's successful, it's definitely been a really fascinating project and I think all of us have learned a lot from it. Not just myself, Jerome, and Sarah, but also Mdou, Moustapha, who worked on the film, Mdou's brother, who was a big part of our team as well, and all of the cast who were involved. It was a very intense learning experience about how we worked together. And how to make a movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHgEuzv-zNA

Do you think you're going to make more films?

Well, I've been joking that I should just start a production remaking 1980s movies in West Africa, like we do Police Academy--

Die Hard cuts a little bit too close, I think.

Yeah, right. But yeah, I'd like to work on another film. I've got a lot of projects that I'd like to work on. I'm really interested in doing something with the director over there for a next project, so somebody who already is shooting films and can find actors. Cause there's a lot of good actors. I mean, even in Agadez, we found actors. We didn't know about them but once we were there, we found a couple professional comedians and they were amazing and I thought, man, who would have known about these people before? So I'd like to work more with people there.

There's an Agadez comedy circuit?

There's an Agadez comedy troupe--it's like these two guys who run this school and they teach kids how to be actors and comedians.

That's a movie.

Yeah, I mean, they're hilarious. It was great to see. 'Cause if you go to a place where acting isn't a big part of the culture, it's hard to find actors. I mean, everyone's exposed to films so people know what fiction is, but, you know. I think a lot of us have been in at least a few plays as kids, so we kind of grow up with it, for better or worse.

I also want to tell you that one of the most interesting final stages of this project is that I have a contact in Nigeria who works in the film industry so we're going to get like 5000 DVDs made and I'm going to get them distributed across the Tuareg diaspora. You know, send 1000 up to Agadez, 1000 to northern Mali, I'm gonna send some to Libya, some to Algeria. We're not really looking to recoup any of the costs of the DVDs so we're just going try to drop these into different places. So that'll be kind of the conclusion of the project, I think. After the premiers and everything, that will be that final step. So I'm really interested to see what will happen after that.

You mean after all this time of tracking cassette tapes, your finally tagging things and letting them back out?

Yeah. Will this movie be received everywhere? Will people be watching it all over? Will Mdou become a star in West Africa? I don't know. I don't know what's going to happen, but I like the idea of somebody coming to Tripoli or something in 15 years and finding this Nigerian DVD copy of this movie, you know? So we'll see.

Yeah, that's amazing. I really like that. So it sounds like it was kind of crazy but successful.

You know, when I look at it I'm like, "Wow, the fact that we got enough footage and we edited it and you can follow it, and it tells a story--I'm impressed that we did that." 'Cause just shooting something over that short a period, that was pretty hectic.

The making-of movie would have been a more interesting movie than the movie. To the Western audience at least. Maybe even to the Tuareg audience. But unfortunately, we shot some footage of the making-of, we had a second camera man, but we were so short staffed that we just pulled him to shoot the actual movie, you know? "Hold this boom pole ..."

Well, we got a film made, which I think we probably shouldn't have.

The making-of movie would have been a more interesting movie than the movie. To the Western audience at least. Maybe even to the Tuareg audience. But unfortunately, we shot some footage of the making-of, we had a second camera man, but we were so short staffed that we just pulled him to shoot the actual movie, you know? "Hold this boom pole ..."

Well, we got a film made, which I think we probably shouldn't have.