The Rise and Glory of Afro-Montreal

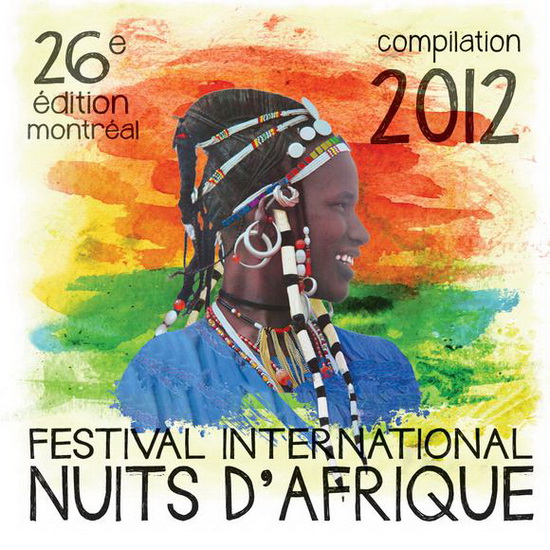

The Nuits d’Afrique Festival in Montreal started in 1987, and for 26 years, has delivered a top-notch lineup of international and local acts playing music from Africa and the diaspora. The big names have always been there—from Salif Keita and Youssou N’Dour to Mariam Makeba and Thomas Mapfumo—and the festival has grown and changed with the times. This year (2012), younger acts like Awadi, Spoek Mathambo, DJ Rupture and Locos Por Juana rubbed shoulders with the likes of veterans Oliver Mtukudzi, Jaojoby, Gnawa Diffusion and Calypso Rose. Over the years, Nuits d’Afrique has also nurtured an impressive cadre of local Montreal acts, from the Algerian-led band Syncop, to Senegalese kora maestro Zal Sissoko, a terrific Brazilian-born singer/songwriter/bandleader named Rommel Ribiero and the Afro-Colombian juggernaut Heavy Soundz.

In the summer of 2012, Afropop Worldwide made an overdue first visit to the summer festival (We’ve caught individual Nuits d’Afrique shows in the past). We found much to admire in the full festival experience—stellar programming, attractive venues, lively but easy-going urban ambiance. Read my report on the Nuits d'Afrique festival here. But as impressive as the festival itself was the multi-cultural and deeply musical character of Montreal itself.

It turns out, these two stories are linked. When I say this festival has “nurtured” an African musical community, I mean that literally. The festival’s founder, Lamine Toure of Guinea, has made it his business from the start to be there for artists, all year around. The Nuits d’Afrique office is a friendly, open-door proposition, and it has rallied to promote and support local artists acts in a way that is rare and refreshing to see. This feature—created to accompany the APWW broadcast “Afro-Montreal and the Progress of Love”—tells that story, the evolution of Afro-Montreal. What follows is excerpts from my interviews with Lamine Toure, Nuits d’Afrique general manager Suzanne Rousseau, and Montreal based artists, Zal Sissoko, Rommel Ribiero and Karim Benzaid of the band Syncop.

Banning Eyre

Birth of Afro-Montreal

LAMINE TOURE: Me, I am like an opening. An opening at the disposition of the public. Everything that I do with my team, we are always asking ourselves, is this good? Have we done a good job? And it is you, the public who must tell us, if it is good or it is not good. Because we, we work all year long to make this Festival. So when the Festival arrives, we think that the question goes to you, the public. You must say whether it's good. If the public tells us that there's something missing, we must listen. That's how it is with us.

Above all, in life, in order to evolve, you must travel. When you don't travel, you cannot evolve. Nuits d'Afrique--as we created it, we knew that not everybody can buy a plane ticket and go to Africa. So we said, we're going to create something so that now the people who don't have the means to go to Africa can still understand Africa, right here in Montréal. That's why I have needed my brothers here, and also my American friends. We also need the African Americans to come and see this, because it will give them pride. It will tell them where they came from.

In 1974. I had been here for a month, and I was supposed to leave. Two days before, I was in a café, Casa Pedro, I saw someone, an African, pass by the window. I went out to call him to come and sit and have a coffee with me. And I said, "Young man, I've been here for a month, and I never saw you. Now I see you as I'm about to leave." When I said that, I saw this guy he had become completely silent. Afterwards, I saw that he began to cry. And I said, "Hey why are you crying?" He said, "You must not leave me in the desert. Since I have been in Canada, I have never spoken my maternal language, Sousou. It's the first time." I said it's not true. You cannot tell me this.

It's true, we were not numerous then. From all of Africa, there were only about 50 people in Montreal. So this guy did everything he could to make sure that I would stay here. I was at a hotel. He told me to take my bag is from the hotel and come stay with him. He was there to help me. And this is how I came to stay and stay here.

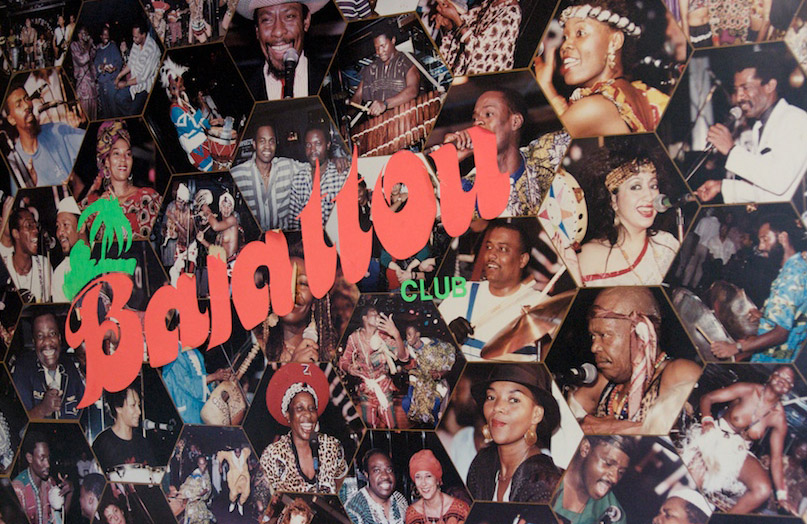

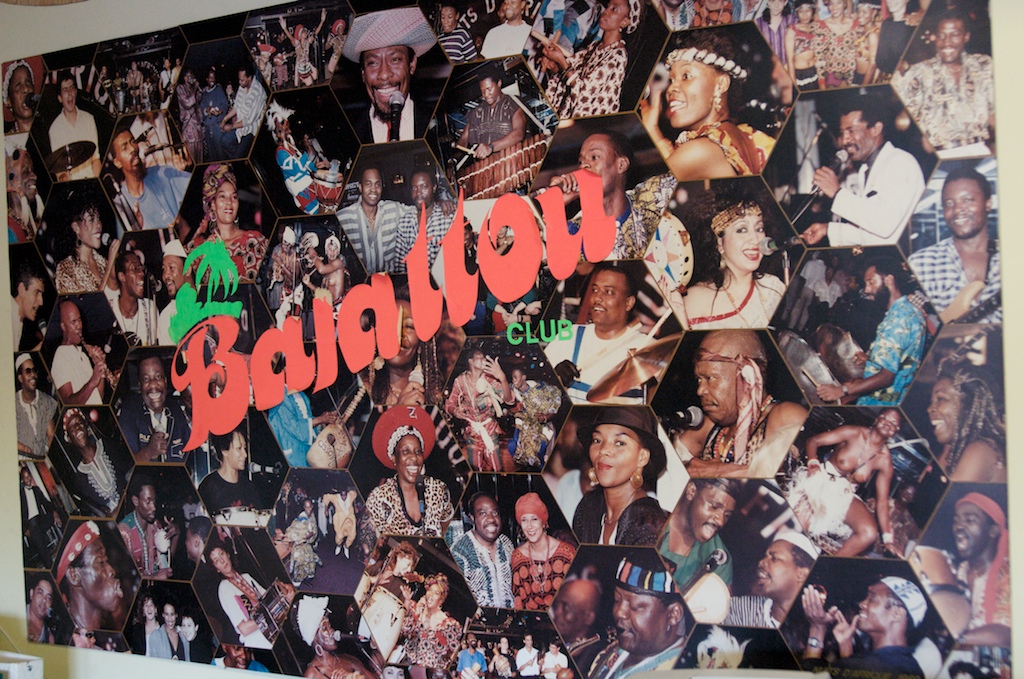

Club Balatou

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: The Nuits d'Afrique festival started in an indoor club, Balatou, a club known for its world music, where we are sitting right now. It has only 150 seats.

LAMINE TOURE: This is my second club. The first almost called Café Creole. I started it with a Guyanan, Alex Boicel. I associated myself with him. When we started, taxi drivers started to bring strangers. People started to arrive. From the airport, straight to Café Creole. But we saw a right away we had a problem. We had made a room there, we brought two beds. And each person who came, we put them up and fed them. Afterwards, we brought them the next day to see Immigration. Then as soon as that person brought their papers and put them into the hands of the government, then another one would come. And we continued that way for five years.

Two years later, my clientele let me open a nightclub. No, the public demanded that I open a nightclub. So I said to the public, "Wait, there are five right now. If I open one, there will be six. That's too many." They said, "The way that they are doing it and the way that you do it are not the same thing. We want you to take your place." And I said, "Well, if I take my place, will you be with me?" Everyone said yes. I asked the Latinos, and they said yes. I asked the Haitians, and they said yes. I asked the Africans, and they said yes. I asked the Québecois, and they said yes. So now this gave me the courage to open Balatou, with a name that was in the spirit in which they came to me. “Bal a tous,” a ball for everyone.

The wave of immigration had been going on for awhile. In that time, there were many people coming from Ghana. From Ethiopia. Afterwards where? Congo and Cameroon. There were a lot.

You see these posters? It was we who started doing that in Montréal. We were the first ones to put up posters like that in the city. We did that at the time with paper, and magic markers. Now, we were doing publicity with the federal government at our side. We got our publicity to all the media, to everyone.

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: Balatou gives us the pulse—the artists, the artistic scene. And the public keep meeting at Balatou all year long, so we know culturally who are the newcomers, who have been here a long time and what they are up to.

The First Edition of Nuits d’Afrique

LAMINE TOURE: Woah! It was big, that one. The first image of the Festival Nuits d'Afrique, we did that with Fatala, with Loketo, and with David Mutukuli...

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: Well, it was in 1987. It was a 15 day event. The festival was born at Club Balatou. Balatou had opened its doors in 1985, and the festival began a year later. The first edition of the festival Nuits d'Afrique was created with Mr. Toure. He is really the person who makes sure that the heart of Africa is presented in its authenticity, its culture, its respect for others. And when I look back, from the very first edition, the name “world music” didn't even exist. But from the very first edition, we presented international acts and local acts. The local acts weren't as many and varied as today. It was a very small community.

But when I look back, I am impressed that from year one, we had international names. And here, there was no music in record stores. We had to do everything from the start. We had to write up the bios of each artist we were presenting. We would bring them by hand from the artists to the media. We'd make copies of CDs that we had bought from Melodie in Europe. We had nothing. That's why it's a very strong at Nuits d'Afrique because we always did everything ourselves, and we always make sure that the music and the artists were presented in a way that honors who they really are.

Growth of Nuits d’Afrique and Afro Montreal

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: The first outdoor edition started in 1990. It was right in front of Balatou, on St. Laurent Boulevard--one small stage, with a little bit of a market. And the outdoor edition was one day. It grew slowly. The second year was two days. St. Laurent Boulevard, which separates East from West of Montréal and is an important street, is not so wide, so, eventually, we had to move because the festival was getting too big. So in 1995, we moved to a park, a little east of downtown. Now, we could receive more than 10,000 people at once. So we had a bigger stage, a variety of artists, local and international, outdoors. With the Timbuktu market, workshops, outdoor crafts and market.

During the festival, we really see how Montréal is multicultural. When we have Nuits d'Afrique, it's not just Africa that's out there. It's Lebanon, Japan, China, all people who come from a different country who have the social sensitivity, have a special tie to Nuits d'Afrique, because the festival brings out this very humanitarian energy. I see every year some people who don't go out all year, and this is their meeting place. They come with their families, little kids, mixed black and white, yellow and black and red and black. It's beautiful. I have been doing this Festival for 26 years, and the thing that keeps me excited is really this part of the festival.

I think that many years back, they brought over a lot of specialized professionals from Haiti. There was a need here. I see there are still a lot of doctors from Haiti. There's a story there. I don't know the whole story, but the French Canadian community is important. But the first ones who came before them were the English Caribbean community from Trinidad and Jamaica. In the years I’ve been working in the festival, I've seen a lot of influx of Africans, especially in the years from 1988 to 95. But since then, I haven't felt that same influx and I'm wondering why. Because I remember this special year I felt a big community of Malians coming. One year it was a lot from Somalia. Another year it was Ghana. Another year was Ethiopia. Now, it's a little bit more North African.

Artists of Afro Montreal

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: Local artists feel like Nuits d'Afrique is their home. They come and see us without any appointments. They know it's their home. If they need anything... we are not formal with the artists. We help them out. We are not commercial, where you have to have a contract with us or else were not going to help you out. They need a place like us in order to grow. They need somebody to structure them and help them. They can't know everything about business, and they feel it. Those who understand. Zal Sissoko is somebody who comes every once in a while over trying to create a project. He comes and gives us his idea, and he's part of the project. We create events together.

Five or six years ago, we created a program of musical honors called Les Syli d'Or (The Glolden Elephant), the music of the world, and it's for Canadian artists. And every year, I wonder how are we going to regroup 36 groups that we haven't met yet were exposed to the public? And for the six years, every year, we see how many new artists are here, or artists that we haven't known yet. 36 groups in two months play every Tuesday and Wednesday, and the public votes. And these showcases give artists the tools to succeed. They get a video from it. They get professional pictures. They get a CD. It gives them a website. It gives them the tools to promote themselves internationally.

There is a Haitian artist called David Bontemps, who has a classical education, but who mixes traditional Rara music with classical piano. It's very original music. He's a beautiful person. The mix is fresh and original. There is Charly Yapo who used to be part of the group Les Go de Koteba in Ivory Coast. He has been living here for many years now and has been a long time bassist a very well-known Québec artist named Jean Leloup. He's a little bit wild, but very well known here in Québec, and Charly just produced his own album with us, and we'll see them at the festival there this summer. Again, he's from Ivory Coast. He mixes reggae with his Mandingo music, and he has done it in a very fresh and original way. He invites singers of different origins for each song to give a different ambience. He's got a Jamaican singer. He's got a Haitian singer.

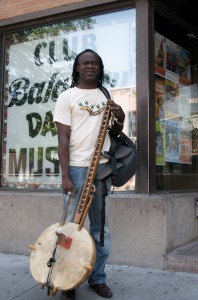

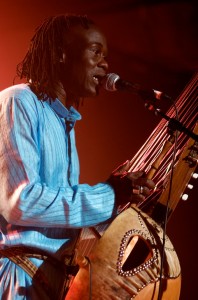

Zal Sissoko

My name is Zal Idrissa Sissoko, originally from Senegal. I have lived in Montréal, in Québec, since 1999. I play the kora. I come from the Sissoko family, the griots, the African library. Because as you know in Africa, griots are very important. They're people who transmit tradition, history from the Mande Empire from generation to generation. The South is Senegal, the Cassamance is the granary of Senegal. Because you know many of the things you find in the North, fruits, and rice, these things are grown in Cassamance. It is one of the most fertile regions. The soil is very rich. It's also a very multicultural region.

Senegal was the South East part of the empire of Mande. Going towards Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea Conakry, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, all the way to Mali and Burkina Faso. All of that is the Mande Empire. So, yes, you are very much in the middle of that in Cassamance. You have Guinea-Bissau just a few kilometers away. On the other side you have Gambia, also very close. And then Guinea Conakry, and then Eastern Senegal, and then you are very close to Mali. From Kedougou to Kayes. It's close, and you can eat lunch in Tamboukounda.

I had a contact with Nathalie Dusseault, a woman who played kora, and her husband who was here. They came to visit Senegal, and Nathalie learned the kora in the family. We were together with others, and made a group that traveled. But I really liked Québec, and I decided to stay here and work in 1998.

For me, we mustn't think of these immigrants in Québec or Canada as forgetting their roots, losing their culture. Because music is about reminding us who we are, and it is very important to keep us connected to the realities of our history.

In life, you must share with other cultures, because each exchange of music I give something and I get something in exchange. It's enriching for me. I've played on some 15 different albums with artists in Québec. Including with Corneille, who comes from Rwanda, and recorded a very good album here. He's very well known here. There is X the Montréal jazz group, young guys from Québec who play jazz fusion. Jubilitation Gospel Choir, a Montréal choir. I've played on two of their albums. Les Frères Diouf who come from Senegal. Lilison di Kinara, who come from Guinea-Bissau. Muna Mingole, who comes from Cameroon. Sara Rénélik who comes from Haiti. Dandigra Dan Bigras, Québec musicians. Losnak Lusnak who come from Armenia. These are some of the collaborations of it involved with. It's super.

For me the role of griot doesn't stop at just sending a message. It's about introducing people from different cultures to my own. I bring something, and they bring something also. Because the kora is an interesting instrument. In the tradition, it is played for the Kings. But today, the kora has become one of the most revolutionary instruments. You find it in every style in the music in the world. You can find it in jazz, in Afro-Manding, Afro-Brazilian, hip-hop, Samba, salsa....

I've been here for 14 years, and I have seen a lot of people arrive. That has allowed me to learn a lot, and share a lot. I can bring things of my own origins in my own culture, but I also get something back. I have a group called Buntalo that I've led since 2004. We have two albums on the market. We are six musicians—Ivorians, one Malian, and Canadians.

I've been here for 14 years, and I have seen a lot of people arrive. That has allowed me to learn a lot, and share a lot. I can bring things of my own origins in my own culture, but I also get something back. I have a group called Buntalo that I've led since 2004. We have two albums on the market. We are six musicians—Ivorians, one Malian, and Canadians.

If I decide to work with a traditional song, I keep the traditional side. I may change the

words and make my own arrangement. But when I compose, I compose new words and new music. Because me, what inspires me to compose is what I experience, what I see every day, my rapport with other human beings. The things that I see all over the world. These are the things that inspire me to write. I have a song called "Pouquois." Why? I ask the question why because we are in a world today that I don't understand. Among human beings, we find people who are just here to kill other people. We have presidents who are ready to kill their population in order to stay in power, and others who've kidnapped children and kill them because there is a separation between the father and the mother. These things happen. And what I'm saying is that human beings were not created for such things.

Another song is "La Presse." I wrote this because in the West, when you read about Africa, you think that everyone in Africa is poor, dying of AIDS, in poverty, in wars, destroying the forest. And in Africa, when you read the press, you think that everyone in the West is rich. But I find it vice versa, Africa is not just poverty and disease, and bush. Africa is beautiful. And in the West, you find that many people are suffering. In the press, what I've seen about Africa is not what I know of Africa, and what I've seen about the West is not what I know in the West.

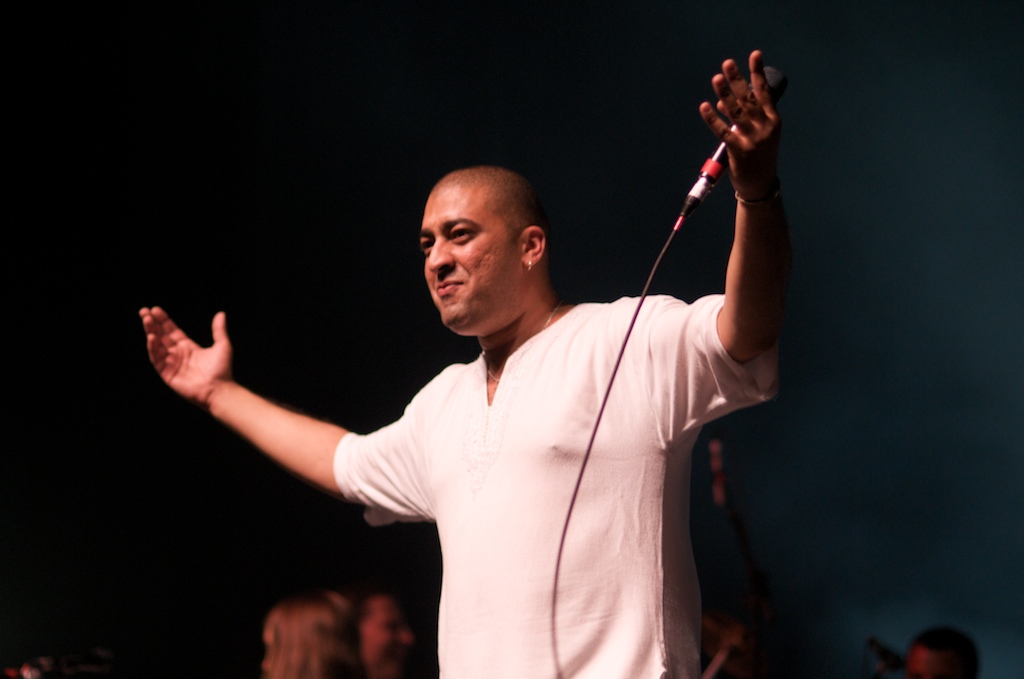

Karim Benzaid and Syncop

My name is Karim Benzaid. I'm a singer of the band Syncop, and I've been here in Montréal since 14 years. Here, it's a French-speaking country. The history of Algeria is it was colonized by France. It was impossible for immigrants from Africa to go to Europe, because it was saturated there. So because of political turmoil in Algeria, we went to Tunisia. After that, we said that we can't go back to Algeria, so we decided to come to Québec, to Montréal.

Before, I was a singer, but not professional. I started in Tunisia. I started to do bands with friends

to sing rai and chaoui music, to find my origin. Chaoui is the music of the high plateau, in the east of Algeria. It's a region that goes to 1200 meters in altitude. It's the Berbers, but not the Kabyle. It's the Berbers of the high plateau and they have a festive music, but very particular. It's done with a whole troupe of bendirs, and it's a music essentially made to get horses to dance. There are a lot of shepherds and a lot of horses, and they use this rhythm to make the horses dance. And then since there are a lot of mountains, there's a style of singing that you could hear from one mountain to another. That’s the kind of sound I wanted to find when I went to Tunisia. So when I came here, I just continued. I met musicians, and I started the band Syncop.

The base of our music is North African rhythms. But this music is created with influences from the members of the group. We have people from Algeria and Morocco, and we have a French guy. There are people from Côte d'Ivoire. I sing both in French and in Algerian dialect, and then all the influences of the others come in. But we are not trying to glue together different styles. For example, on the song "Trabando," the first song on our CD, there are Latin rhythms. But there is also a rhythm inspired by Congolese soukous. But it's not soukous per se. I actually work with some musicians from Congo. And there were some girls singing, "Na lingio." I asked what does this mean? And she said, "I love you." Ah, that's perfect. Is that I'm going to put that on the chorus. So "Trabando" is the black market, everything that's a little bit illegal. And this is a little bit the life of a musician. That's where this word trabando came from. You're trying to bring things that don't exist. During the 1980s in Algeria, it was trabando. And I could say that all musicians do a little bit of trabando. Because they don't exist officially, outside of festivals.

It is magic in Montréal. Almost every night, you can find music, world music—never mind the rest. And in the end, we get to know each other, you get to know the others. If I had stayed in Algeria, this would've been more difficult. Here, we become one community and we absorb each other's influences. Normally we would use the oud. But we could also use the kora. On the song, "La Cabane à Souk," I used Zal Sissoko on kora. For me, this was completely normal. In the same spirit, my oud player, Mohammed Masmoudi, has worked with Zal on some projects. This is something that the Montréal artistic community has given us. I have sung in Arabic with friends who play rumba, and Latin music.

Sometimes a colleague will say, "Come, I have a song that is a little bit Arab or Berber." I say, "No. Play your own style, and I will add in something to your style." Because if people try to make something that is a little like rai or chaoui, and they aren't familiar with the style, they are likely to come up with something that's a little bit cheesy, a little bit kitsch. So I tell people not to do that. Play your style. That's the best. Because if you listen to the drums, the way they play, the way the accents are, where the one is, one can learn the style. For us as artists, you can say, that comes from Congo. That comes from Senegal. That comes from Cameroon. If a song has a certain rhythm, a certain percussion that works particularly well. The people who make this music know exactly how it should be, the way one should saying, the way the singing should be. If you're going to play a style of music, you have to study it.

Our second CD is called Sirocco d'Erable. Sirocco is a wind. It's the hot wind of the Sahara. It brings the sand to the European countries. It's a hot wind. Very hot. Erable is maple, as in maple syrup. We call it in French syrop d'erable. So here with my culture, we have the hot wind coming to mix with the Maple, it's a double meaning. A mixed identity. That's what we are today in Montréal in July, after 14 years spending our time doing music. We meet people. We have a lot of influences from all over the world. So I became that wind, the syrocco. And I live here, so the Maple is always around us.

Rommel Ribiero

My name is Rommel Ribeiro is I am from San Luis de Maranhao, It's a city in the northeast of Brazil, in a province of Maranhao. My musical education comes a little bit from there. Because my city San Luis is a very rich city in terms of folkloric and original sounds, really roots. We have so many kinds of drums and Brazil--tambuja criolla, bumba me boy, cacuria. It's a very very rich place in terms of culture. It's kind of inspirational.

I used to play guitar since I was seven years old. My father started me on music, and gave me my first lessons. But when I was 14, in my school, we used to have competitions of composing. And for like four years in a row I won the Festival, the competition. But most of my education is from the bars and Brazil. We have a lot of bars where musicians come with a guitarist and they are obligated to play all the songs that are being played on the radio, and all the classical Brazilian music, from bossa nova, to samba, forro. So for me it was a great school, because I had to learn about 400 songs to play. Learning the songs of the masters of bossa nova and popular Brazilian music made me able to start composing find my own style.

I have been six years in Canada. I came when I was 19 years old. I came to Montreal from Ottawa, to go to school in audio production course. It's very interesting in Montréal. This is a city of transients, with a lot of people who come to play a show and stay for two days. There are lots of parties in the middle of the night, you can always invite some interesting musicians, some interesting people, some interesting artists.

We have a band with five musicians, two Brazilians, another French guy, one from Cameroon, and one from Lebanon. Each one brings his own experience and we try to share. For me it's great as a composer and musician, to have people with different backgrounds playing my music. I feel that makes my music bigger and gives it another color. It's really great. I really love Montréal in those terms. I just got an award from Radio Canada. There are so many different activities we are doing in the year. I'm very happy with everything that's happening now.

I just released a new album called Egologico Recycle. I'm making a word play with Ego and logic. Because I'm talking about individualism in the society. Everybody wants to think that it's only them. But to do this kind of work, it's important to share, to reach out to all the world, and all the musicians around me. Producers. People who really have given me support. I think that today in this world, if you can live together, it's very important to share. So that's a bit the idea of the CD.

We are always in contact with Brazil. Everything that happens there, we know here. For me it's great too, because I have my own audience in Brazil too. They follow me through Facebook and Twitter. It's very dynamic and fast. It's really good. I appreciate that.

[caption id="attachment_5826" align="aligncenter" width="643" caption="Sara Nacer and Banning Eyre on the job at Nuits d'Afrique 2012"]

Sara Nacer and Banning Eyre on the job at Nuits d'Afrique 2012

Building a Multi-Ethnic Community

Tapa Diarra (Eyre 2012)

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: Through Club Balatou, people from Africa and the islands have come to know each other. Mr. Toure is here every night to make sure the people feel welcome, and that this intercultural mix is working. Today, it's easy. But back then, it was harder because they didn't know each other. So through the music, because we mixed the kinds of music, people from the islands started to discover their roots in Africa through Balatou. That's why the feeling that ties them to Nuits d'Afrique is so deep, because this work is being done throughout the year with club Balatou and Mr.Toure. For him it's really important that people whose origins are African know where they came from. And very often he tells the story of why he created the festival, especially the outdoor portion. He'd see little kids on the street, and their moms were white Canadians, and they’d have a little black kid and they’d see Toure, and a kid would say, "Oh, daddy." A few times that happened, so Toure said, "Okay, there is work to be done." This Festival has to go out. So that the kids know where they come from.

KARIM BENZAID: I am a Montrealer. All the musicians from Montréal, they are going to tell you we are

Montrealers. We are trying to make known our origins, and the colors of Montréal. And we are many. And with the public that follows us, we try to say to people and to the media that exists that we exist, and they should recognize us for our value. We do shows, we do tours. In the past 10 or 15 years, it's been different. There are lots of international artist who come. They are known by the public. And there are local artists who make albums, and work in a very professional way. And this is a beautiful thing for Montréal, and for the public to follow us.

We all started with Nuits d'Afrique, all of us, without exception. Festival Nuits d'Afrique has always been there for us. And it's all thanks to the team of Mr. [Lamine] Toure. For example, the first time Mr. Toure saw our show, he let us finish the show. After that, he spoke with us. It was Toure who helped me be discovered as a musician in the first place. 1999, 2000, 2001, he came to a rehearsal in a studio nearby. He called me. I came to Balatou. We listen to music, watched video clips. He told me about this artist, that artist. He gave me CDs, DVDs of various artists, just to work my musical imagination. And when we did a show, he gave me advice, watch out for this, watch out for that. He does this for all the artists. He is the spiritual father of world music.

The Challenges Ahead

SUZANNE ROUSSEAU: Actually, the work I would like to do is to have the French and English communities mix more. Which is strange, because everybody else does mix.

ZAL SISSOKO: I can tell you that African music is going very well here right now. During the 1990s, it wasn't so evident. African music was very limited, except for Nuits d'Afrique. Now people come to discover the African music here. So it's advancing. But there is still work to do. We have to do more than that. For example in the Montréal Jazz Festival, there will be one group, or two groups of world music. Festival Francophonie, it's the same thing. So the diversity and the platform, the window into the world music, it's mostly the domain of Nuits d'Afrique.

Syncop on stage (Eyre 2012)

LAMINE TOURE: I will tell you this. Everything that has started in Montréal, all the African immigrants in Montréal, no matter where they come from, all of them love Montréal. But where there is a problem is that they don't have work. That is what holds them back. I remember when I created a soccer team here. We called it Tournament Balatou. Ghana had two teams here, because there were many of them. Congo too, because there were numerous. But now, they've all left. Toronto. Calgary. Vancouver. You see? Because there is no work here. But even with that, they come back. I saw one of them yesterday. Someone I hadn't seen for a long time, but he was in Montréal yesterday. He came to see his town. Everyone loves this town.

But what we have done is only a start. For me it's not enough. This festival—for me, the first one who has to support it is the city of Montréal. It's for them, this city, those who run the city. It's created for them. Those who govern the city. We are just an opening. They have to be real partners with this festival so that we can go further. Because on the economic side, it works. But the moment there is economic success, there is tax. And this is the biggest African Festival in the world. It's not me who says that. It's the journalists, the people have been to all the festivals. This is unique in the world.

There is African blood in the Caribbean. Africa created the Caribbean. There is African blood in America. That's Africa. But now, if we would really be aware of this history, aware of all that has come from Africa, the day that we all understand that together, you will see that Africa changes. But if we don't understand that, we will not change Africa.