As we charge into a new golden age of vinyl, prestige labels continue to repackage classic releases in a format that has risen like a phoenix from a widely presumed obsolescence. Among these labels is the standard bearer for Americana and global folklore, Smithsonian Folkways. Just out is a set of three vinyl LPs: Calypso Travels: Lord Invader and his Calypso Group; Gambian Griot Kora Duets Featuring Alhaji Bai Konte, Dembo Konte, Ma Lamini Jobate; and Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahara. As it happens, these titles revive rich memories from three phases of my own journey into African diaspora music, and that’s all the more remarkable as I am hearing all three albums for the first time on these reissues. I’ll take them in corresponding order.

This collection of 13 spicy tracks was recorded by Moses Asch with Lord Invader and his band in 1960, shortly before the calypso icon left this planet. At the time I was four years old, but a few years later, our family moved from rural New Jersey to Montreal, where my father was tasked with running a shipping company owned by Alcan Aluminum. Since Venezuelan bauxite was a key ingredient in aluminum production, these ships frequented the Caribbean, notably Trinidad. As it turned out, the ships my father oversaw were on the way out as they were too small to accommodate the coming wave of container transport, but that’s another story. During our decade in Montreal, we all visited Trinidad and were hosted at the Trinidad and Tobago pavilion at Expo 67, and those experiences made a mark on me.

On a drive around Port of Spain in 1967, we stopped to eat, and were serenaded by a busking calypsonian wielding a guitar. In his song, the singer noted that my father bore a distinct resemblance to John Kennedy—true. My mother, who played guitar and collected folk songs, explained to me that calypsonians had to improvise lyrics, responding to whatever was before them and creating a song, preferably with rhymes, on the spot. I was fascinated. We returned to Canada with tourist-stand steel drums, which my brother and I did our best to wear out—not easy. As a kid, I continued to listen to calypso, and although I understood its historical significance no more than I did that of the Leadbelly albums my mother liked to play on the old Victrola, these sounds had me.

Now on this Folkways volume I listen with renewed delight to Lord Invader sashaying glibly into commentary on such sensitive subjects as the rise of Fidel Castro (Castro say he’ll never surrender/You know he’ll make a sad Batista), black kids being kept out of schools in Arkansas (I think that is high class ignorance/You are afraid of the negro’s intelligence) and a crime wave in Trinidad (I say the only thing to put down this crime is to bring back the cat-o-nine), all the while boosting himself as the king of calypso (The Lord Invader will never surrender/I’m the Lord Invader, master calypso singer.) There’s even a playful song about drag (After the dance the leader of the band/Said Lord Invader you were dancing with a man.) The music is as irresistible as the clear-eyed innocence of the lyrics.

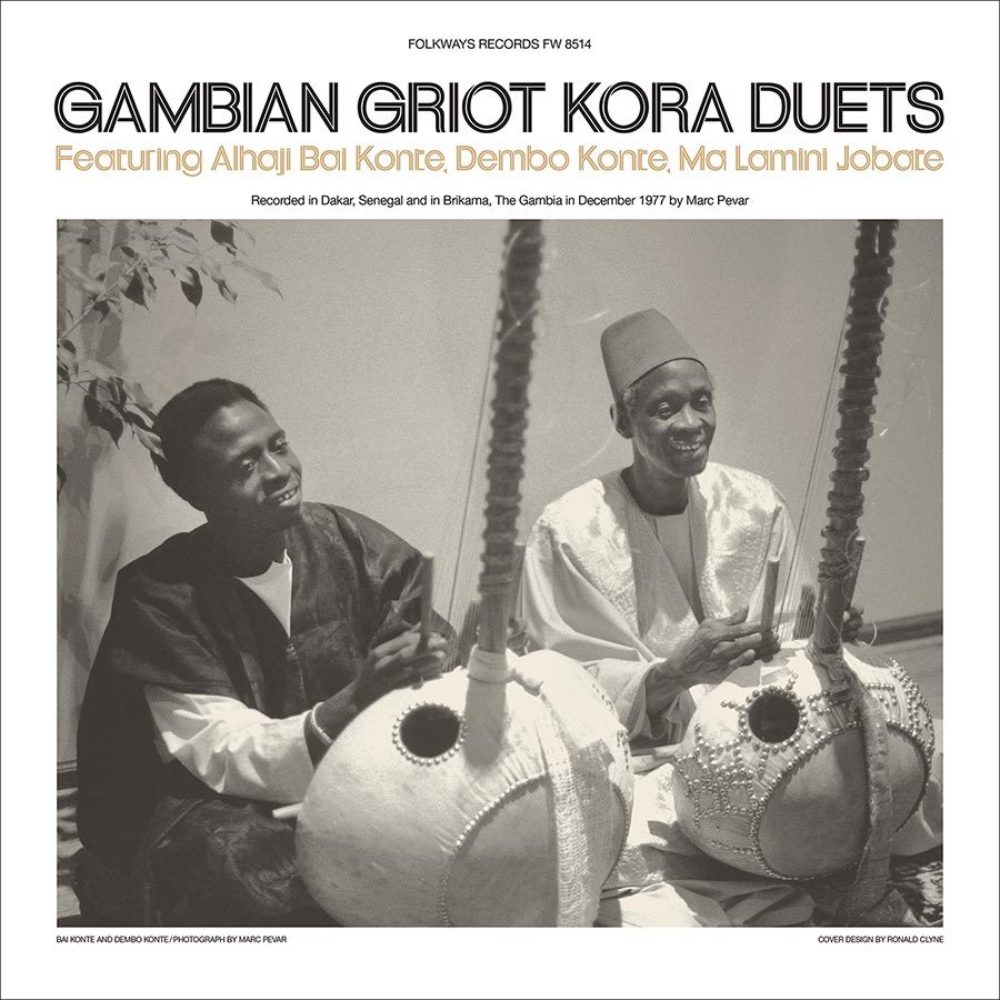

This one takes me back to my first discovery of kora music, which immediately reminded me of folk and ragtime guitar picking I had grown to love. In fact, it was a fellow sophomore at Wesleyan University, none other than future Afropop founder Sean Barlow, who introduced me to one of his favorite LPs, the 1973 Rounder Records release of Alhaji Bai Konte, Kora Melodies From the Republic of Gambia. When this Smithsonian volume was originally released in 1979, Bai Konte had made two U.S. tours, including a concert in Washington, D.C., where Sean had his own fateful “ah-ha” moment.

I have lived with that Rounder release ever since, but am only now hearing the Smithsonian volume thanks to this vinyl reissue. Gambian griots, or jalis, have a very distinctive sound. Racing kora riffs and male vocals, usually sung by the player, distinguish the genre from, for example, kora music in Mali, which is generally calmer and more ethereal—while no less virtuosic—and most often accompanies a female griot singer (jelimuso). There are more musicians in the performances here than on the Rounder release, but the character of the music is unmistakable. Hearing the keening voices of Bai Konte, his son Dembo, and Ma Lamini Jobate singing in unison over the propulsive pump of dual koras is as beautiful today as it was 45 years ago, and for me, profoundly nostalgic.

The other difference between this recording and the Rounder release is the length of songs. The Rounder set includes 14 tracks, only four of them topping six minutes. The Smithsonian set has just five tracks, only one less than eight minutes. These longer selections feel more like the way kora music would actually be performed in situ. Both of these pioneering kora albums were recorded by the same person, Marc Pevar, a largely unsung champion of Gambian kora music. In fact, over the past couple of years, Marc has been busy arranging a tour featuring the grandsons of the old masters he recorded so long ago, Jali Bakary Konteh and Jali Pa Bobo Jobarteh. (Don’t fret the spelling anomalies: I am following the versions favored at different times, hence the inconsistencies.)

Marc’s notes for the Smithsonian release capture the reality of 1979, when West African music was either unknown or brand new to American listeners. His comments hold up well. He explains how a Mandinka king Ndaba Jali Konte came to Casamance in the 19th century, during the regime of Samory Toure in Guinea. The Mandinka musician king later switched from the kontingo lute (a likely banjo ancestor) to kora, and after his son Alhaji Bai Konte was born, the family came to settle in the Gambian town of Brikama, a center for kora musicianship and learning to this day. Marc deconstructs the four common tunings of the kora and, interestingly, dates the instrument’s creation to just around 300-350 years ago. Tell that to Toumani Diabate, who routinely claims to come from 70 generations of kora players. I will let scholars sort out the math, but there seems to be a discrepancy…

All this reminds me that I did a fascinating interview with Marc Pevar last year, and I need to get it transcribed and posted before the Great Gambian Griots tour begins at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in April, the INS willing... Stay tuned for details on that tour, and keep an eye on https://www.africanculturalencounters.com for more on the tour and learning opportunities.

The third Folkways reissue in this set dates back to 1960, the same year as the Lord Invader session, though it could hardly be more different. Tuareg music lacks the obvious appeal of Mandinka kora or calypso. It is truly the sound of a place, and that came into focus for me only when I covered the Festival in the Desert in Essakane, Mali, in 2003, and then became a fan of folkloric groups like Tartit and the wave of Tuareg desert rock set in motion by Tinariwen. Now the sound of melancholy Arab-tinged voices intoning over patient, persistent, unhurried hand percussion instantly evokes visions of the vast Sahara with blinding sunlight bathing sensuous, shifting sand dunes. I’ve had a hankering to return to that environment since the moment I left it.

This Folkways release is unmistakably a set of field recordings from that distant world. On the opening track, “Tuareg women of the Tamesguidda tribe,” we hear the voices of women in animated conversation, then breaking into song backed by the women’s tinde drum (spelled tendi here) punctuated by ambient hubbub and ululations. These 13 brief tracks feature chant-like vocals by women and men that are reminiscent of other Berber traditions, also handclaps, pulsing grooves and the near-human cry of the imzhad one-string fiddle. The recordings are clear and crisp, not exactly high-fidelity but powerfully evocative.

Finola and Geoffrey Holiday made these recordings and their liner notes are as interesting as the music itself. In addition to providing rich cultural detail about each track and the circumstances in which it was performed, the notes offer a telling historical artifact. They describe a mysterious Berber people with a unique, matrilineal social structure, an “opportunist” take on religion—Arabs called them “the Abandoned of God”—and little or no recorded history. These observations were made for the original 1960 release, coinciding with the dawn of Malian independence. This, of course, is the exact moment at which many Tuareg of today believe that they were unjustly subsumed into the new Malian state, beginning a struggle of autonomy that continues today and remains a stubborn thorn in the side of the nation. These notes and the music they accompany provide an excellent preface to one of Afropop Worldwide’s program "The Tuareg Predicament," which explores the origins of the ongoing conflict.

So for me, these three albums have me rehearsing the long, strange trip I’ve been on all these years. Hopefully, for younger listeners, they may mark the beginning of stranger trips to come.