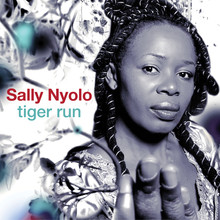

“Welcome into Hollywood world,” sings Sally Nyolo in the song “Welcome,” on her new album, Tiger Run (Riverboat Records/World Music Network). The tone is dark, cynical, caustic: It’s a caution, a warning against Hollywood-ization, against a devouring kind of globalism. Nyolo’s singing is cold and stern, matched by female background vocalists and the relentlessly burbling rhythms of her band. It’s a powerful statement, even if you don’t understand any of the other words, which are sung in French.

That this song is the literal and figurative centerpiece of the album is telling. As much as ever since her mid-‘90s stint in Belgium’s female vocal ensemble Zap Mama, she embraces globalized glamour. There is polish and sheen aplenty. European sounds abound. The title song is in English. So is the ostensibly African-oriented “Kilimanjaro.” She veers toward French chanson here and there. And on “Le Faiseur de Pluie par Tous les Temps” (which translates as “The Rainmaker in All Weather”) she achieves a long-held ambition to work with an opera singer—soprano Nathalie Leonoff.

But never better has she blended her Cameroonian origins with her Parisian upbringing in one singular vision throughout an album. And apart from the chill of “Welcome,” the album is marked by a warmth, carried by Nyolo’s supple voice. Most of the songs are in her native Eton language. And every song, no matter what else is going on, is built on the percolating drums of western central Africa. She cites the chants of the rainforest pygmies of her home region as an influence, and very much the celebratory 6/8 rhythm bikutsi dance styles—both traditional and modernized—found there.

That strong foundation is established right off the bat with opener “Bidjegui,” Nyolo and her vocal companions starting with an a cappella bikutsi chant, soon joined by a percussion ensemble led by the Ivory Coast’s Paco Séry and then rubbery bass lines from Mali-rooted Papus Diabaté. From that she goes confidently in various directions, while maintaining a forceful identity tied to the Africa of her childhood.

“Me So Wa Yen” has a pace and pulse that is almost electronica, but without the electronics—organica, perhaps. “Tiger Run,” the title playing off the origins and meaning of her family’s traditional tribal name, is slinky soul. “Eeeh” is a bit of acoustic high-life. “Elle Regard Passer” could easily go torchy, but the drums keeps it rooted in the village. “Medjok” uses guest saxophone by Michel Graillet to take things in a whole other, jazzy direction, particularly in an improv outro over acoustic guitar.

And then with the closing “Tiga,” Nyolo strips it all down again to percussion and vocals, but with Carlos Leresche’s flute floating through for an unexpectedly lovely combination. It’s a perfect reduction of the pleasures and powers of Tiger Run. This is not traditional music. But at the same time, it’s not not traditional, or at least not removed from her traditions—those she carried from Cameroon and those she found in France. She doesn’t go in for the grand gestures of, say, Angelique Kidjo. And yet her nuanced artistry creates its own grandeur.

Hollywood? That’s a whole other tradition on which her thoughts seem pretty clear.