All photos by Mike Benigno, used with permission.

Even when he's acting his most normal, Tom Zé is up to something. There's just something unstoppably impish in the Brazilian composer and singer, something that's only getting stronger as he gets older. For instance, about halfway through his set last Friday, he picked up his guitar for the first time all night and he and his band launched into "Vai (Menina Amanhã de Manhã)" from the 1976 classic Estudando o Samba. First the bridge popped off the front of Zé's guitar, then the neck came off, then the front of the guitar, then the back. Then his percussionist bound the remaining frame of a guitar's body to Zé with an apron, and Zé coquettishly pranced around the stage wearing it for the rest of the song.

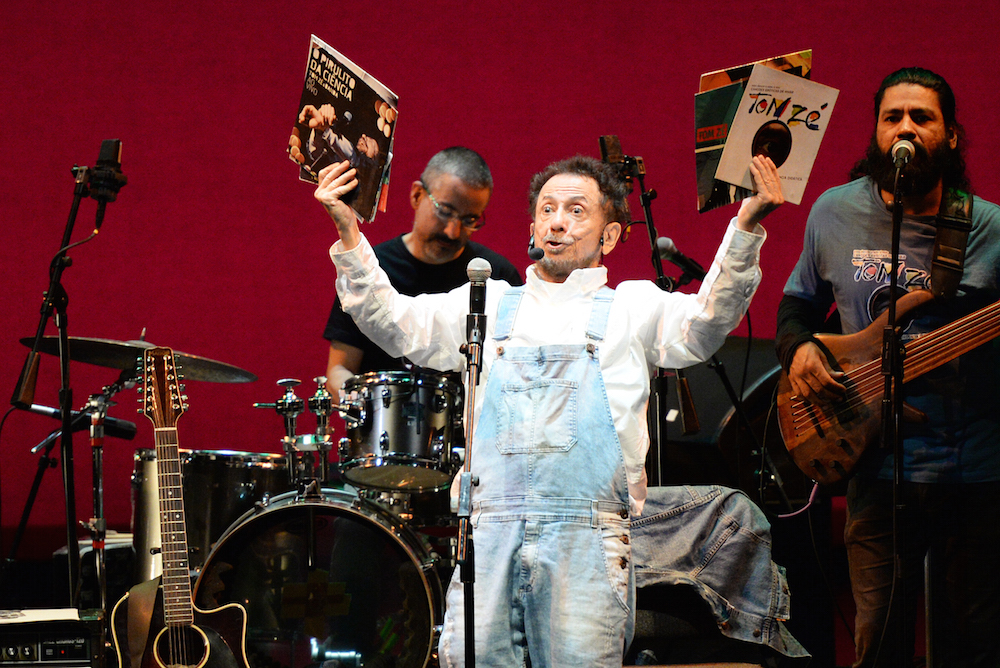

The concert, presented by the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the World Music Institute, was the first time Zé had played in New York since 2011. The show managed to capture a lot of what makes Tom Zé an endearing, enduring, and occasionally enervating artist to follow or listen to. Sometimes the gaps between songs, delivered in Portuguese and broken English, seemed as long as the songs. Sometimes the songs would start only for Tom Zé to wave to his band to stop, so he could resume his monologue. He hopped down off the stage to ask people with help translating words. Young at the age of 80, he comically produced a bright red pair of women's underwear and shimmying them over his overalls.

Tom Zé was one of the original Tropicalistas of the late 1960s, penning the song “Parque Industrial,” included on the Brazilian pop-art movement's seminal album, Tropicalia ou Panis et Circensis. The restless Zé was a man apart, however, and he moved to São Paolo to release an extremely challenging body of work: post-modern “studies” of Brazilian samba and pagode music, songs where vacuum cleaners are played like instruments. As the story goes, his Brazilian audience dwindled through the '80s and he remained mostly unknown beyond his home country's borders, until David Byrne, conducting his own study of samba, stumbled across Zé's Estudando o Samba. The Talking Heads' frontman was struck by the album, which somehow straddles the avant-garde and playful bliss. Zé's back catalog found an American label, and an American audience, and soon he was releasing new music again. Last October, shortly after his 80th birthday, he released an album about how he learned about sex.

After a hearty and warm introduction of his band, member by member, Zé launched into the opening track from that 2016 album, Sexo. While Zé is a restless performer, whose proclivity to wander meant he had to wear a wireless headset microphone in addition to his mounted mic on stage, his band was incredibly tight. Even when Zé's music is at its most peaceful, he's apt to set the song on a complex polyrhythm, and the five-piece backing band never fell off the asymmetrical beats.

For two hours, Zé made jokes in between his often comical songs, no doubt to much confusion among those in the house who didn't speak Portuguese. But Zé's music explores serious, political themes—sexuality, intergender politics, the relationship between the developing world and the developed. He has called his music “sung journalism,” a fact not lost on the crowd, or at least not lost on the Brazilians in the crowd. During his final song, the aisles filled with an even mix of dancers and people bearing banners, the largest one reading, “Volta Dilma,” imploring the ex-president, ousted in 2016, to come back.

Up in front, still clad in his bright red undergarment, Zé fed the fire. Doing some silly, not in opposition to political statements, but as one.