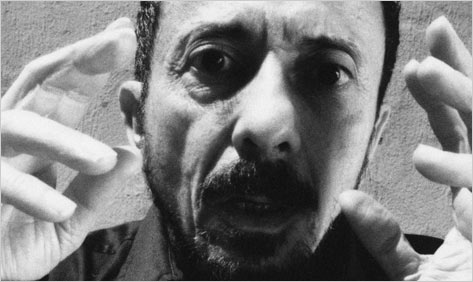

In a small auditorium at PUC São Paulo, a top private university, Tom Zé blesses twenty students, two professors, and some kid who helped him carry in the speakers, with a private concert. Calling what happened on Friday, June 29th “a concert” might not give readers the whole scoop. Although music was played, and although the audience sang along, demanded an encore, and even found themselves asking for autographs, only one song was sung in its entirety. Then again, why should we have expected anything like a “concert,” given Tom Zé’s distinct demeanor?

Tropicália was an avant-garde artistic movement that in a few short years beginning in the late sixties attempted to bring modernity and an open mind to Brazilian popular music at a time of a military dictatorship. Many tropicalists came from Bahia, one of the poorest states in Brazil, and the “crazy” Tom Zé is no exception. Crazy isn’t our description of him, it’s his. His excuse is simple: he was born to die.

Zé began his performance with a monologue about life in a tiny town in Bahia. Nine months after being born, his mother could not produce enough breast milk to feed him. He believes the devils cursed him and he was not supposed to live. The devils, he claims, never though he would find a busty Bahiana wet nurse to give him the flow of life. She, he deduces, must be the reason for his insanity. And she we should thank for giving Tom Zé the inspiration to be anything but normal.

Zé wasn’t always an experimental Tropicalist. Growing up in Bahia, his musical education consisted of a combination of oral folkloric tunes and a formal degree at a fine music school. His move to São Paulo, however, was what gave the man in the auditorium inspiration to write about what few others had before: beautiful São Paulo.

For the first half of his career, Zé’s unusual style plagued him with unpopularity. In the 1990s David Byrne, an American musician, rediscovered Zé’s music. The same music that caused Zé to slip into obscurity in the 70s and 80s is the music that today makes him one of the most popular Brazilian musicians.

The only way to become a real Paulistano (resident of São Paulo) in the 1960’s was to talk about how much Sao Paulo sucked. Most didn’t completely think so, but the idea of a big city was tough to swallow for migrants from tiny towns around the country. Ze’s song, “São São Paulo,” perfectly captures these “paradoxes” by starting off with the couplet:

São São Paulo, quanta dor

São São Paulo, meu amor

Sao São Paulo, how much pain

Sao São Paulo, my love

Although this song won him the 1968 popular music festival prize, he remembers nobody saying “quanta dor” and everybody repeating “meu amor.”

This was his style. Saying the taboo and singing the musically unusual. Throughout his concert he reminded the audience at least five times that he was no gifted musician. He was, however, willing to do what others hadn’t, and that became the root of his popularity.

After tearing off his clothes while singing about the development of São Paulo, Zé picked up his second guitar, which we soon noticed didn’t actually work. Well, not like a guitar, anyway. Instead, he took the instrument apart piece-by-piece and ended up playing a hidden harmonica while straddling the microphone. Best of all, he took what was left of his instrument and tied it to his stomach with a skirt, symbolically giving birth to the guitar. That man can work up a room, even in his mid 70’s!

Before ending with a sing along, Zé rocked out to “Augusta, Angelica, e Consolação,” a song about three major streets in São Paulo. He picked this song to brag about “the best line he ever wrote,”

Quando eu vi

Que o Largo dos Aflitos

Nao era bastante largo

Pra caber minha aflicao

When I noticed

That the square of the afflicted

Wasn’t big enough

To contain my affliction

He then made his guitarists repeat the line. Six times. But isn’t that, after all, what makes him a genius?

The show ended with hugs and kisses in the most literal sense. Tom Zé kissed every girl in the room and reminded them to be sexually emancipated.

A Tom Zé end to an already unusual São Paulo concert!