Vinyl LPs bookend my career as a music writer. When I began in the late '80s, thin, square cartons containing promotional record albums arrived regularly at my doorstep. Now, after 30 years of CDs, shelves of which now festoon the walls around me, the vinyl is coming back again (along with countless MP3 download links), and I have to say, those 12-inch discs are more wonderful and more appreciated than ever.

Two label retrospectives have recently arrived, one celebrating 40 years of reggae production by the VP label, a prime mover of post-Bob Marley reggae and its many variants, and also World Circuit, a prestige source of exceptional music mostly from Cuba and West Africa over the past 30 years. It’s hard to beat the pleasure of sliding these beautiful black discs out of their white paper sleeves and hearing the palpable punch of a dancehall reggae 12-inch single, or the vivid clarity of a World Circuit session at Havana’s Egrem Studio pouring forth from the tall speakers in my living room—likely purchased in the 1970s, and still sounding terrific.

Down in Jamaica: 40 Years of VP Records

In his extensive survey of early reggae session players, Words of Our Mouth: Meditations of Our Heart, ethnomusicologist Ken Bilby writes, “no matter how much we think we know, there is always more — much more — to the story.” This is certainly the case with reggae, even when confined to Jamaica where it all began. Bilby’s 2016 book introduces us to foundational reggae musicians you’ve probably never heard of, going back to the music’s origins in Kingston in the 1940s.

Down in Jamaica accomplishes something similar for the reggae of the post-Bob Marley era. The box set includes four seven-inch 45 rpms with B-side versions of the songs featuring long, DJ-friendly instrumental breaks, and four 12-inch extended play singles that more or less combine the A and B sides of the earlier format. These vinyl discs offer mostly collectable classic from VP Records’ early days—though one track, Romain Virgo’s “Fade Away,” (2015) has never been released in physical form before. The discs highlight sub-labels from VP’s early years like Roots, Upsetters, Lightning and Jah Guidance. Then there’s a four-CD set with 82 tracks spanning 1977 to 2017 and tracing the many twists and turns of reggae styles and stars through those years. And crucial to this box set package is a large format, 24-page booklet that offers loads of historical and catalogue information as well as nostalgic photos from VP’s remarkable bicontinental journey.

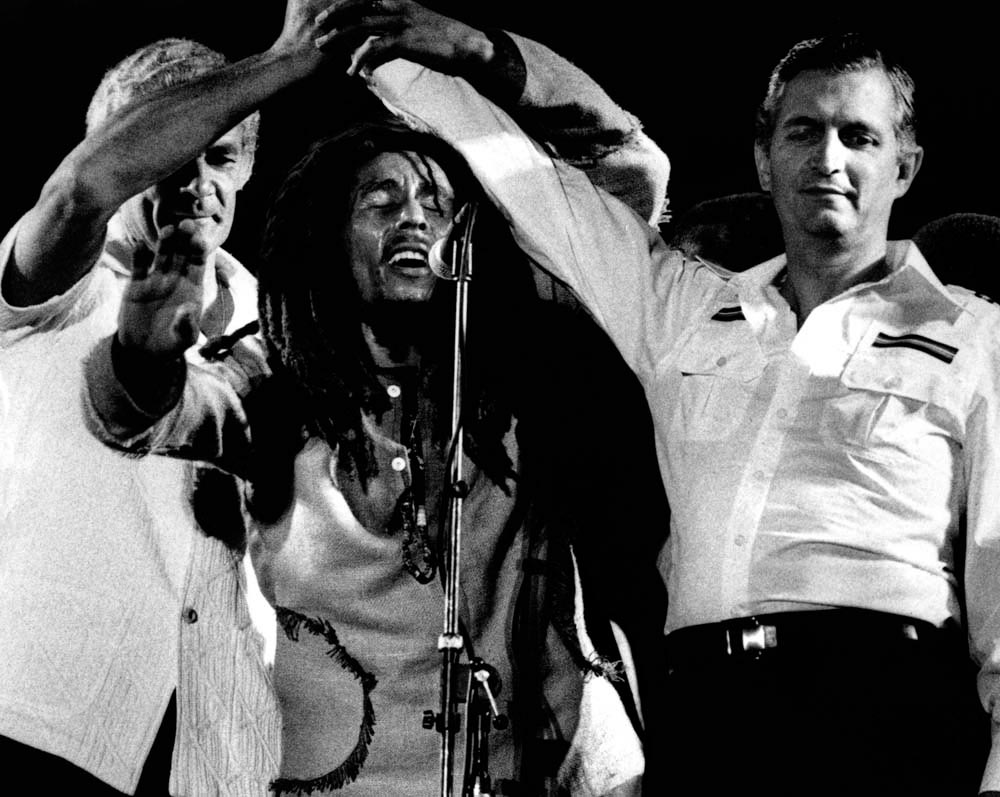

My own love affair with reggae is mostly confined to the years that fall in between these two sources, particularly the 1970s. I turned on to Marley, Cliff, Toots and Spear as a college student, and by the late ‘70s, I was the guy who would slip into your party with a cassette, seek out the sound source, pop out the disco and hijack the dancefloor with pulsing skank and wail of my new Jamaican heroes. As the ‘80s wore on, dub captivated me briefly, but didn’t hang on, and by the time dancehall took over, I had moved on to African music and, newly overwhelmed, did not pay close attention as reggae’s shape-shifting evolution continued apace.

This box set turns out to be a fine way to sample much of what I missed. VP stands for Vincent and Patricia Chin, who opened Randy’s Record Mart in Kingston, Jamaica in 1958, a time when the city was kicking out volumes of ska, rocksteady and early reggae on vinyl. The Chins started out 20 years earlier with an ice cream parlor, but as Kingston’s world-changing recording industry was pulling into high gear, the parlor morphed into a used record store, and then the city’s premier source for the newest ska and rocksteady releases.

The VP logo first appeared on vinyl discs in 1977. Two years later, the Chins opened a store on Jamaica Avenue in Queens, New York and VP Records became a treasured source of Jamaican vinyl, but also a bonafide label and recording studio. VP has championed pretty much every variety of Jamaican reggae ever since, as well as a decent amount of soca music. Celebrating 40 years, VP can also boast 19 Grammy nominations and one of the world’s biggest reggae catalogues.

The label initially worked with independent producers, not the big names of the Marley era, although VP did release Lee “Scratch” Perry’s classic late-'70s Heart of the Congos and Roast Fish and Cornbread LPs. One treasure in this collection is Scratch’s 1978 seven-inch single “Fisherman,” which features the trippy effects and deeply pendulous groove that remain mainstays of this reggae maverick’s mind-bending work to this day.

The '80s were arguably reggae’s heyday, the time when it became a global music. The decade saw the birth of dancehall, marked by Wayne Smith’s “Sleng Teng,” a VP release. The shift from live to electronic drums—controversial at the time—opened the door to dub and dancehall sampling and a world of sound systems with DJs spinning vinyl like the extended play, 12-inch discs in this set. Jamaica was rocking to the new styles, but it took time for dancehall artists to break internationally. Ultimately the likes of Shabba Ranks, Buju Banton and Capleton did the trick, and the rest is history. Certainly, the pop music of Africa, and much of the world, would never be the same.

The collection booklet notes that '90s dancehall is the most often sampled. 1990 also saw VP release the song that launched another phenomenon, reggaeton. The song is Panamanian El General’s “Te Ves Buena,” which famously sampled Shabba Ranks' “Dem Bow,” another VP title. There’s no doubt this label had its finger firmly on the pulse of the Caribbean in these influential years.

Vincent Chin died in 2003, but the enterprise is a family affair, carried forth by Patricia, the matriarch, and children and grandchildren in various roles. After 2008, VP greatly expanded its catalogue by purchasing the U.K.’s Greensleeves Records & Publishing, and launching a distribution entity, VPAL, bringing in such heavies as Israel Vibration and Ziggy Marley, who both won Grammy nods for the VPAL releases. Nearly 16,000 VP releases can be found on discogs.

The four CDs in this set take us on a varied, mostly chronological tour through this history. Disc one starts right out with the Heptones in a perky 1977 reggae number, “Party Time,” a reboot of their earlier rocksteady hit. Ranking Joe’s preachy “River Jordan” (1980) edges toward the more discursive, less melodic impulses of dancehall. Similarly, Yellowman’s “Zungguzungguguzungguzeng” (1983) is a harbinger of the emerging mega-trend. But the older styles never go away. Leroy Gibbons’s “This Magic Moment,” (1987) is a keening, sweet pop reggae number featuring a one-chord vamp that reinforces the song’s message of frozen time. Freddie McGregor’s “Stop Loving You” (1989) nods back to doowop, and Foxy Brown’s cover of Tracy Chapman’s “Sorry (Baby Can I Hold You Tonight)” points to reggae’s more mainstream pop ambitions. J.C. Lodge’s “Telephone Love” (1988) has a techno soul vibe with pumping bass and a female lead vocal that feels more r&b than roots reggae.

Disc two continues to mix in tuneful roots reggae, like Ini Kamoze’s dub-flavored “Hot Stepper” (1990) and Conroy Smith’s “Dangerous” (1989). But the trend in this era is clearly moving towards the rough, minimalist dancehall style, in tracks like Reggie Stepper’s “Drum Pan Sound” (1990) with Stepper’s growling vocal interspersed by a horn-like, one-note moan. Some tracks artfully combine a DJ and a singer, like “Serious Time” (1991) by Admiral Tibet, Shabba Ranks and Ninja Man, where we get a hook melody interspersed with dancehall toasting. “Everybody Falls in Love” also features back-and-forth singing and rapping by Tanto Metro and Devonte. Another emerging trend here is gospel reggae, not the Old Testament Rasta screeds of the ‘70s, but friendlier fare, like “Lord Watch Over Our Shoulders” by Garnet Silk (1995) or Mickey Spice’s “Born Again” (1995).

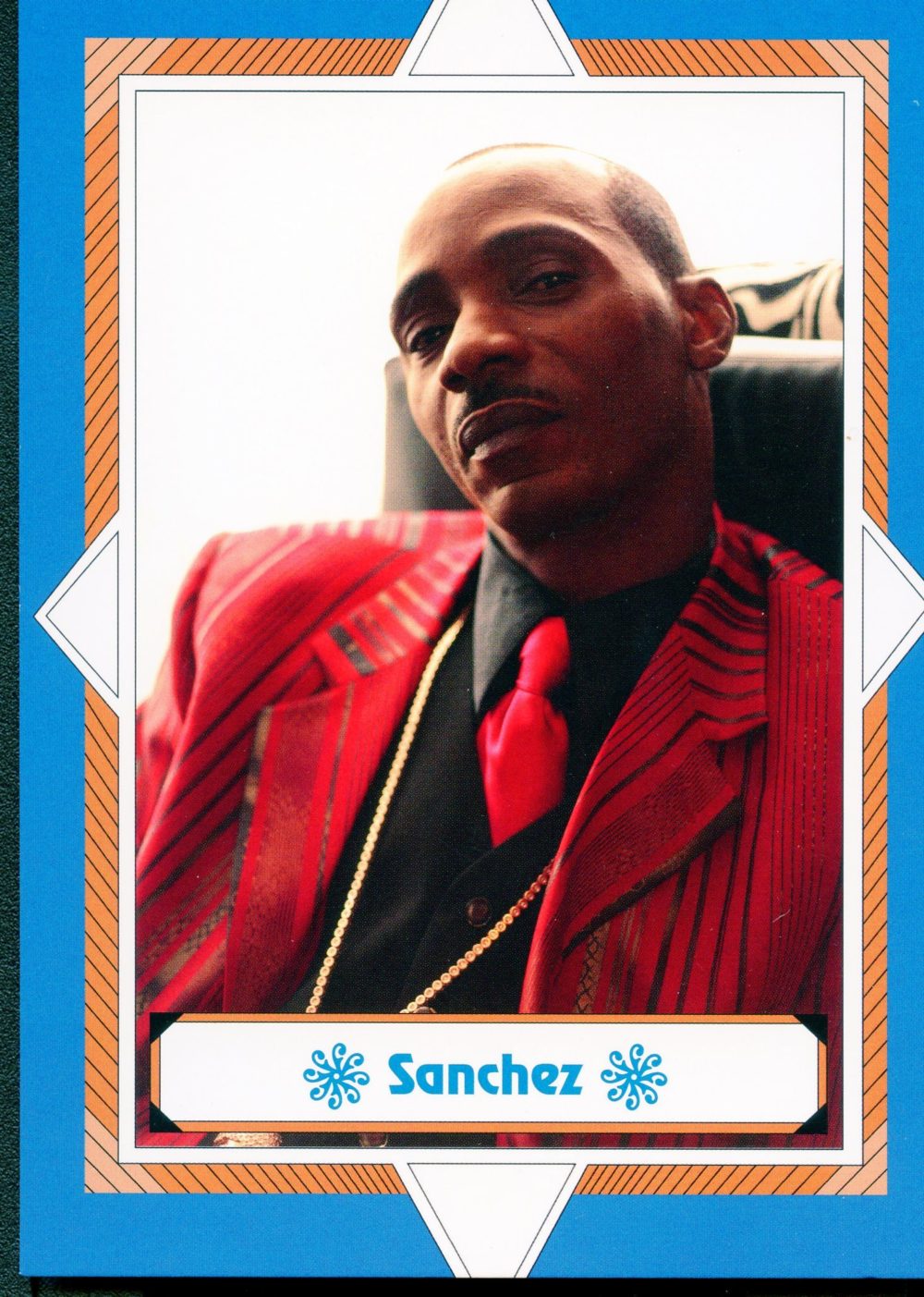

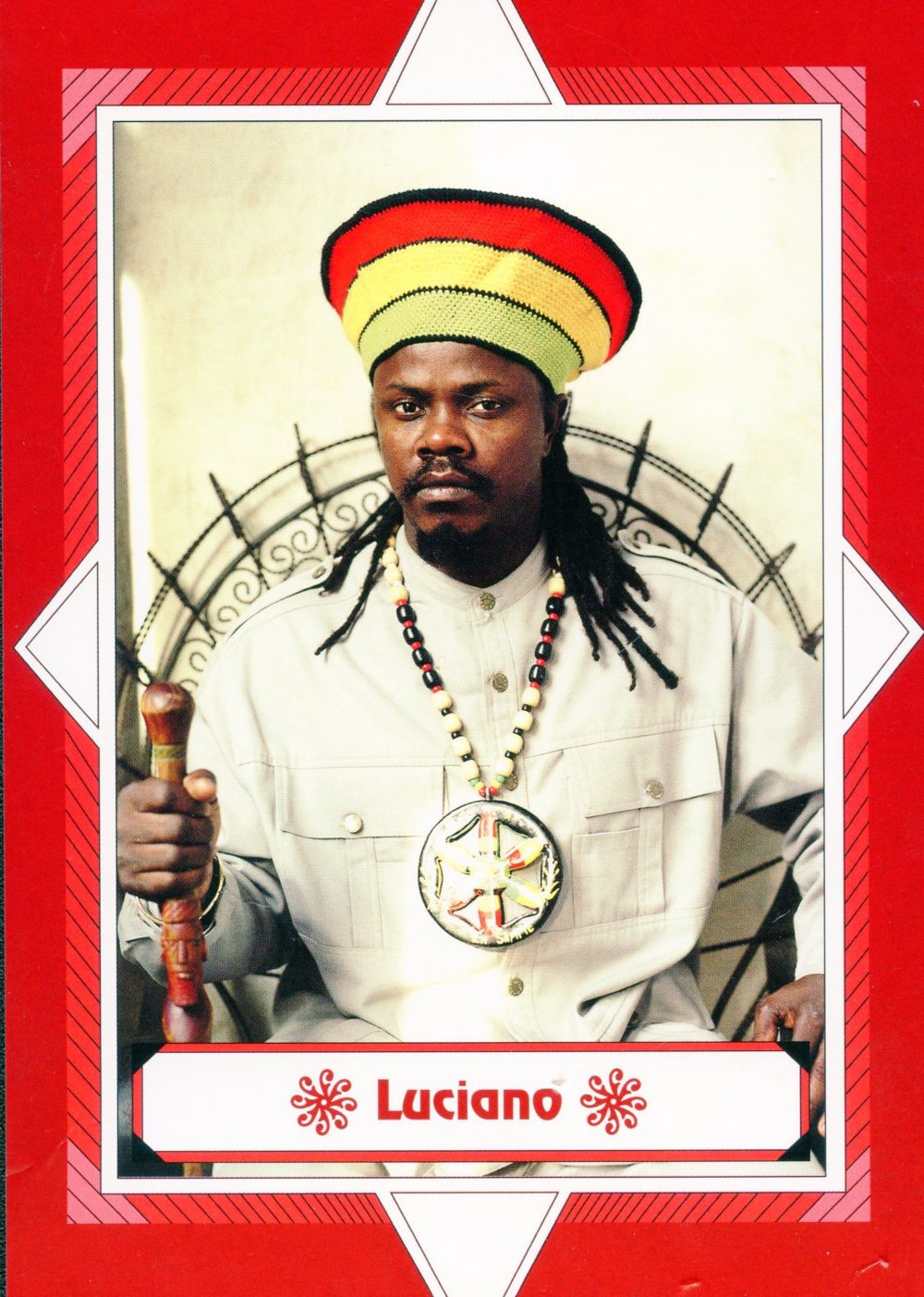

By the period covered in disc three, VP was catering creatively to the DJ market with its Riddim Driven series, albums in which many artists put vocals over the same backing track. Most of the tracks here fall squarely into the dominant dancehall category. But the turn-of-millennium period also brings less “didactic” soul reggae by the likes of Beres Hammond. Around this time, VP artists Sean Paul and Wayne Wonder became “crossover” artists through an alliance with Atlantic Records. For me, Sanchez’s “Never Dis the Man” (1995) is a particularly tasty discovery, mostly for his clear, shimmering vocal. Morgan Heritage’s, “Down By the River” (1999) feels like a nod to the king of soul reggae, Toots Hibbert, and the female backing chorus brings to mind the signature sound of South African reggae icon Lucky Dube. Luciano’s warm “Give Praise” (2004) marks the emergence of a superstar. Luciano was seen as the successor to Garnet Silk, who many hoped would the “next Bob Marley,” a new king of “pure reggae,” until he died in 1994. Lady Saw’s sassy “I’ve Got Your Man” (2004) brings welcome female gusto into play, a trend that continues to gain momentum in the 21st century.

The stylistic blend extends on disc four with soul reggae from Tarrus Riley’s “She’s Royal” (2006) graced with cool brass and gentle, quasi-African guitar riffing deep in the mix. (Tarrus is the son of reggae veteran Jimmy Riley). For me, the standouts here are the more old-school vocal numbers, Duane Stephenson’s “August Town” (2007), Romain Vigo’s “Me Caan Sleep” and Raging Fyah’s “Sash Wata (2016) with its evocation of Marley-style vocals and the refrain of “La Bamba”—all at the same time. History-wise, the important developments in this phase are the further emergence of women, and rise of new superstars Vybz Kartel and Mavado. “Loodi” (2017) by Shenseea featuring Vybz Kartel unfolds with vibey electronics, and you get a little sense of how Vybz Kartel has become the most popular reggae artist in Jamaica since Marley. (Long story there, but another time…) As for women, the collection wraps up with a bang: “Hardcore (remix)” by Jah9 featuring Chronix. A few winters back, I had the pleasure of interviewing roots revivalist Jah9, and catching her rather dramatic stage show on a snowy, sub-zero night in Brooklyn. No doubt, she’s the real thing.

This 40-year celebration is a landmark, but in no way an epilogue. The label keeps the fires burning, boosting reggae revival and lover’s rock acts as the dancehall train rolls on all over the world.

World Circuit

World Circuit founder Nick Gold stands out among producers of the—forgive me—“world music” era. From its start in mid-'80s, this label has shown unfailing taste in bringing to light classic recordings by previously overlooked artists like Mauritania’s Dimi Mint Abba, but especially for producing spectacular contemporary recordings by some of the greatest musicians of our time, mostly from Cuba and West Africa. Lest anyone need reminding, that list would include Ali Farka Toure, Cheikh Lo, Oumou Sangare, Toumani Diabate, Tony Allen, and, of course, the Buena Vista Social Club clan, beginning with the 1995 debut album that remains the biggest-selling album in global music history.

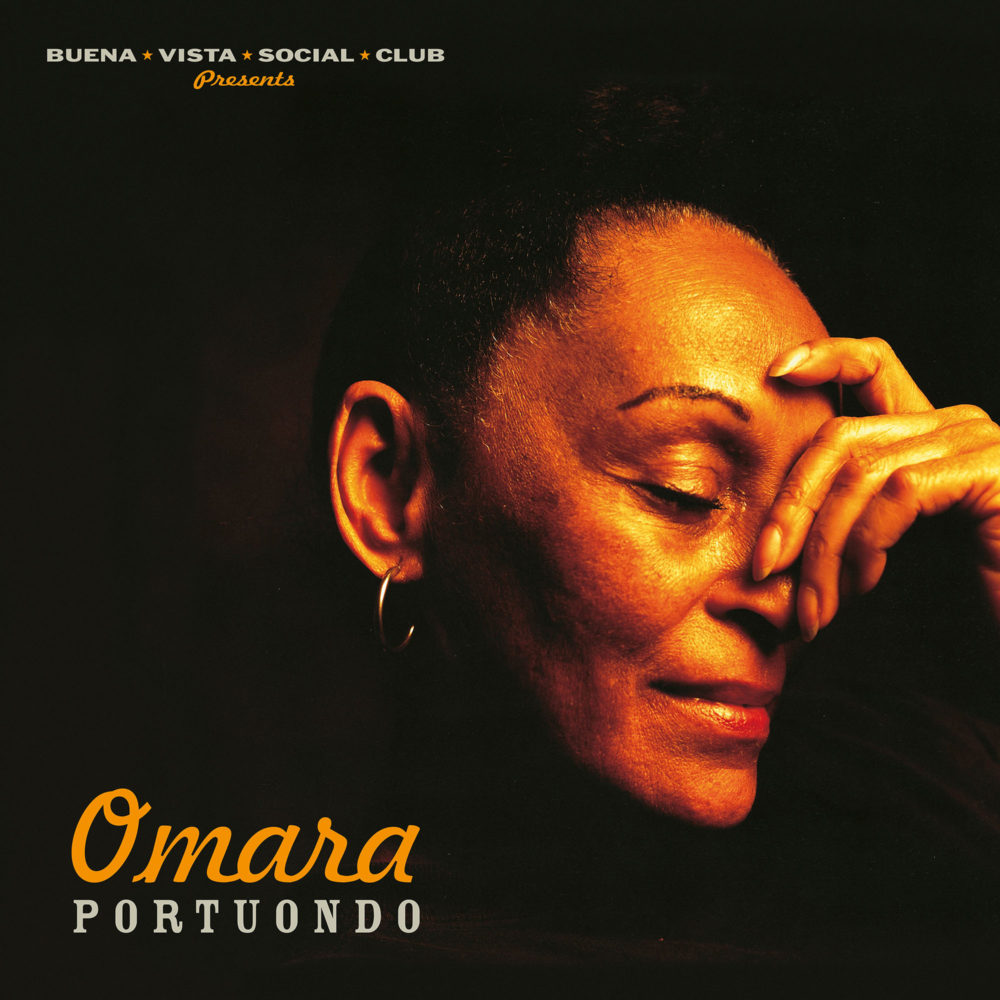

In October 2018, Gold sold World Circuit to BMH, but the label lives on with reissues, streaming features and promised future new releases. One sure sign of World Circuit’s ongoing vitality is a recent spate of remastered vinyl reissues of classic titles with enhanced, LP-sized sleeve notes. Four superb titles have recently appeared on vinyl, and in new digital and CD formats. The four are Buena Vista Social Club Presents Omara Portuando (2000), Guillermo Portabales’ El Carretero (1996), Radio Tarifa’s Rumba Argelina (1996) and Ali Farka Touré’s Savane (2006).

As for the remastering, this aging electric guitarist with high-end hearing loss may not be the ideal evaluator of audiophile excellence, but I can say that these records sound fabulous. Listening now to Ali Farka Toure’s Savane, it is as if the musicians are here in the room with me.

The territory World Circuit covers is dictated by Gold’s personal taste, and there is a compelling logic to it. As any loyal listener to Afropop Worldwide knows, rich history connects the cultures of West Africa, as far south at Kinshasa, Congo, to Cuba, and the vast majority of Gold’s releases emerge from these lands. Early on, World Circuit released music from Cuba’s Sierra Maestra, and the original concept for what became the Buena Vista Social Club was to bring members of that ensemble together with artists from Mali who grew up listening to Cuban music. The idea flamed out at the last minute when the Malians didn’t show. (For more on that, I refer you to my book In Griot Time, as I was in Bamako with the expected Malians when they failed to make the trip to Havana.) With Gold and his team, and Ry Cooder in Havana ready to go, the search went out for veteran singers to fill the gap, and we know what happened next.

One of the autumn-career stars highlighted during the BVSC years was Omara Portuondo. Born in 1930, Portuando emerged as a singer and dancer in the ‘50s. She covered a variety of styles, “filin,” big band, bolero, trova… This album was recorded on the heels of the original BVSC sessions, in the same studio (Egrem in Havana) with the same engineer (Jerry Boys) and many of the same musicians. On the album, Portuondo revisits compositions by artists from Beny Moré to Los Zafiros and BVSC’s Compay Segundo. The book that comes with this package includes gorgeous black-and-white images from the session, and complete lyrics in Spanish and English, mostly about love, and many tending toward the melancholy: Along the path of my sad life I found a flower whose sweet perfume intoxicated me. But as soon as the aroma reached me, it faded away like my soul, sad and alone, like my loveT Rarely has sadness been rendered with such charming elegance. But there are rousing moments of gusto as well, notably the opening mambo, “Donde Estabas Tu?” with its tart brass hits and punchy groove.

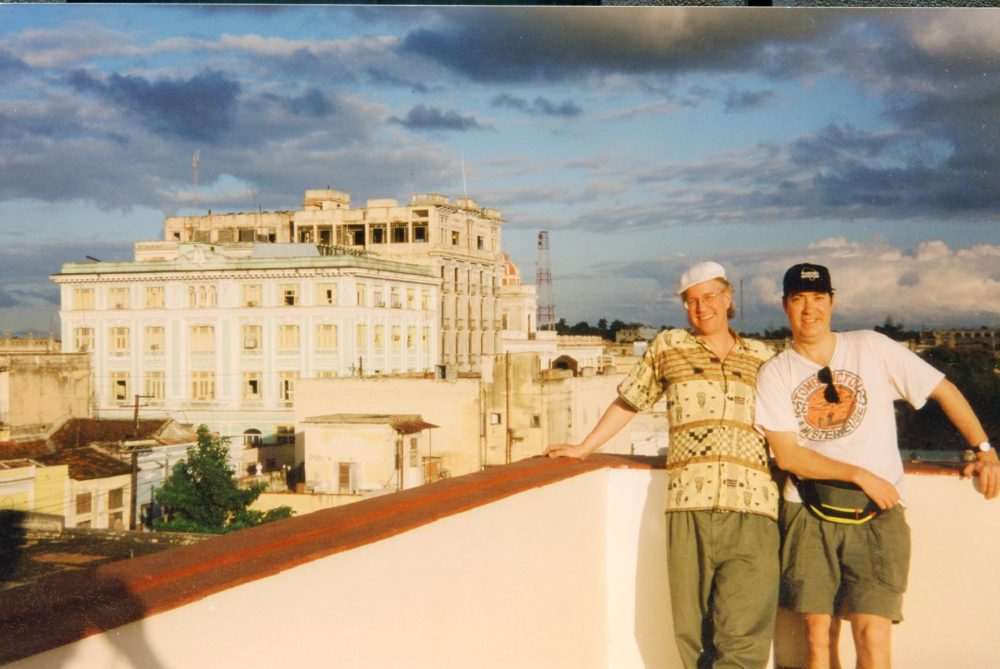

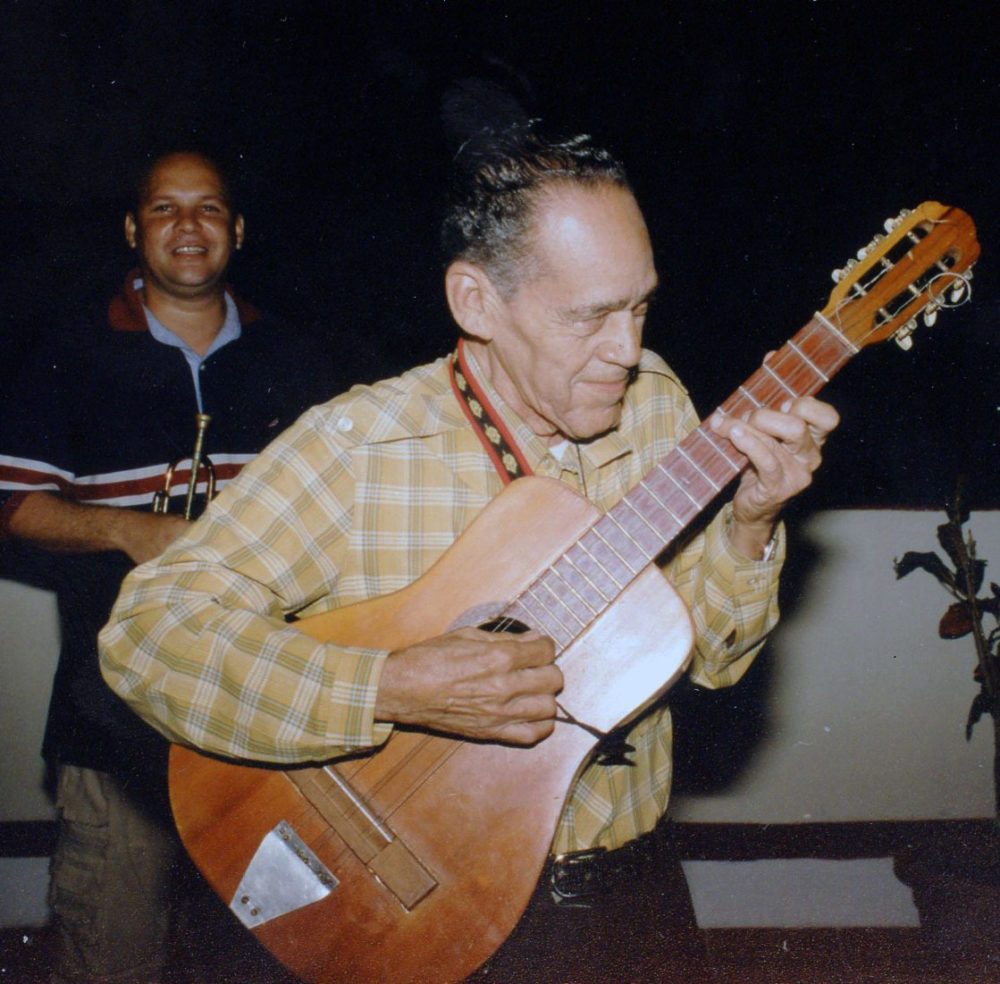

Guillermo Portabales (1911-70) was a guitarist, singer and composer who specialized in the rural guajiro, “halfway between punto and son.” Punto guajiro is a poetic song form that dates back to 17th century Cuba, and has roots in Al Andalus—deep stuff. Son, of course, is the eastern Cuban dance form that fed the development of Havana’s legendary big-band dance styles. Portabales grew up in Cienfuegos, a beautiful Spanish-built town on the north coast of the island that I had the pleasure to visit and sample local son music with Afropop in 2000 in the waning days of the Clinton administration, when travel to the “blessed isle” was relatively easy.

Portabales began performing on the radio in 1928. At first he was a generalist but he ultimately honed in on guajira as a signature style—combining the spare poetry of punto with the melodious, danceable rhythms of son, to create guajira de salon. The staple Cuban clave timeline is ubiquitous, but in the percussion, we hear insertions of ¾ and 6/8 rhythms that reflect deeper African origins. Guajira lyrics deal with the travails and diversions of the peasant farmer. Portabales recorded in the U.S. and Puerto Rico, which eventually became his home, but he always remained true to the eastern Cuban style he adored most.

The music on El Carretero is sublime, very much up my alley: acoustic, rhythmic, playful but with a poignant hint of nostalgia. The album opens with his most famous song “El Carretero” (Down the lane the jolly carter came, so rural and so sincere…) a beloved regional classic that went on to be covered in West Africa by Senegal’s Orchestra Baobab and Cheikh Lô (both World Circuit artists, by the way). The songs on this album are suffused with longing for rural Cuban life: green fields, banana plantations, coconut palms, murmuring springs, lovely peasant girls, bird songs, roasting pigs, harvest parties. They were recorded in the 1960s, mostly in Miami and New York, with small guitar-led ensembles. Of particular note is the song “Voy a Santiago a Morirme (I’m Going to Santiago to Die)” which was recorded with another Cuban ensemble that transplanted to Puerto Rico, Los Guaracheros de Oriente.

Radio Tarifa’s Rumba Argelina (1996) takes us a little outside World Circuit’s familiar territory, but the connections are ample. This is a band whose name and identity are based on a freak of geography—that is, the eight miles that separate Europe from Africa across the Straight of Gibraltar. Growing up in and around Tarifa, Spain, these musicians heard radio broadcasts from Tarifa, Morocco, and it lead them on a journey of discovery regarding the complex cultural ties that linger from the history of Al Andalus, Moorish medieval Spain, which lasted until just before Columbus set out for the New World and the world-changing saga of Cuba’s cultural juggernaut began.

When this album first came out, I enjoyed the music, but had little awareness of the history behind it. Later, when I worked on Afropop’s three-part Hip Deep series on The Musical Legacy of Al Andalus, that history became a fascination, and I returned to this album and others by Radio Tarifa with new passion. Listening again now, I hear the enduring inventiveness in the group’s cross-cultural alchemy. In a mix of vocal and instrumental tracks lies an intricate tapestry of sounds—plucked strings, wooden flutes and reed horns, frame drums and voices that hew a line between the gruff angst of flamenco and the serene choral chants of North African Sufis. The album’s 15 tracks fill two vinyl discs, and it’s a journey well worth repeating.

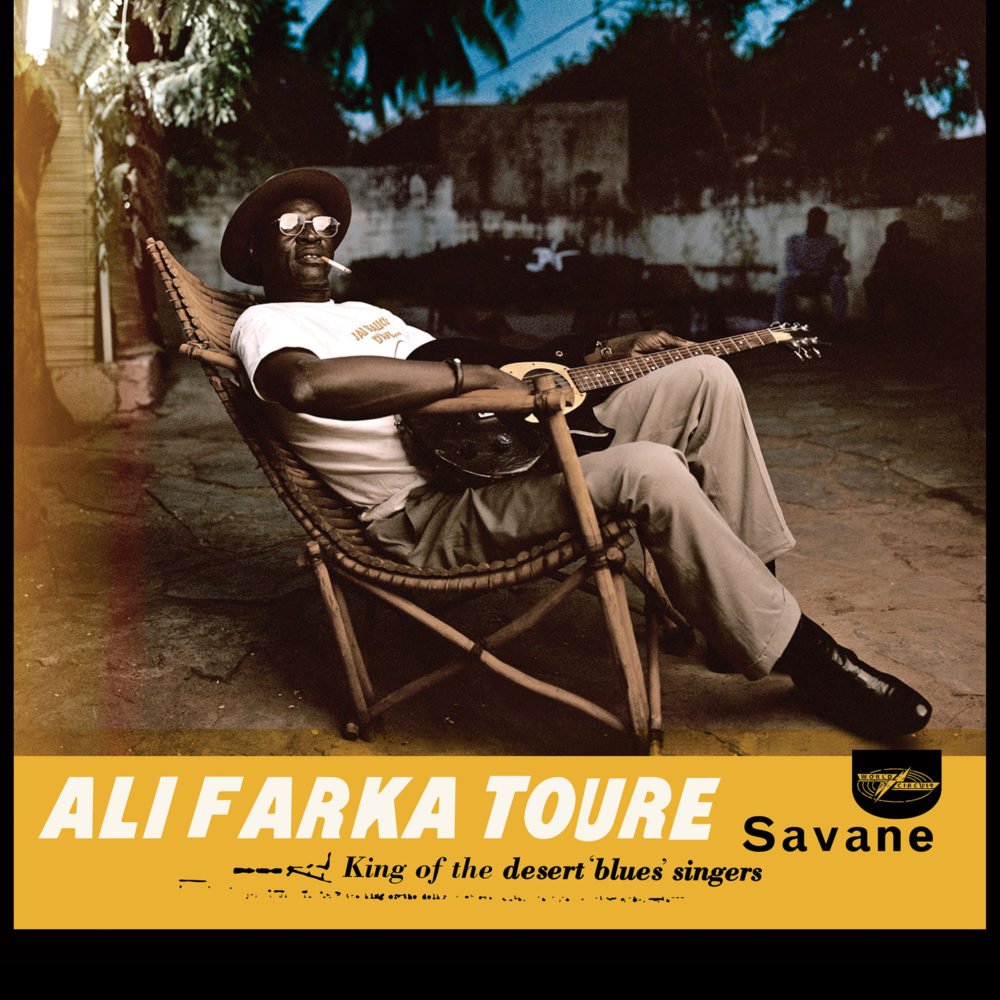

Last, we come to the piece de resistance, Ali Farka Touré’s Savane (2006). This is the northern Malian maestro’s final studio album and unquestionably a classic. With contributions from the likes of Bassekou Kouyate and Mama Sissoko (on small and large ngoni lutes respectively), this set of songs digs deep into the Peul, Sonraï, Tamachek, Zarma traditions. The lumbering opener “Erdi” starts with a blast of bass ngoni and Farka greeting listeners “Good evening” (Bismila). Then the song blossoms with electric guitar grandeur as Farka sings praises to the Peul herders pastoral lifestyle—in a way not so far from the spirit of Portabales’ guajira.

The Sonrai song “Yer Bounda Fara” offers advice on Malian elections through a merry tangle of ngoni and acoustic guitar lines. “Soya,” a folksy Zarma love song, captures the sunny, romping side of Sahara sonority, while the darkly majestic “Machengoidi” sternly urges Malians to get to work developing the country. In the lavish, photo-filled booklet that accompanies this two-disc edition, Farka notes that for him, words are the most important thing, but that “the music has to be good for people to listen to the words.” Mission accomplished. Long live Farka, and long live vinyl!