Blog May 5, 2017

Voices from the Niger Delta

Our research for Hip Deep in the Niger Delta has been extensive. It would be overwhelming to post entire transcripts of all the interviews we recorded, so what follows is a series of images and interview excerpts. This post follows the trajectory of the show, first telling the story of the Biafran War (1967-70) through the story of composer/trumpetist/bandleader Rex Lawson. Lawson was among the most-beloved musicians in West Africa during the war, and his life was upended by it. Since he lived only a short time longer, the memory of his joyous music is indelibly inscribed with tragedy. Professor Onyee Nwankpa, Rex Lawson Chair at the University of Port Harcourt, takes the lead on telling the story in this extended chain of voices on highlife, war and the Delta.

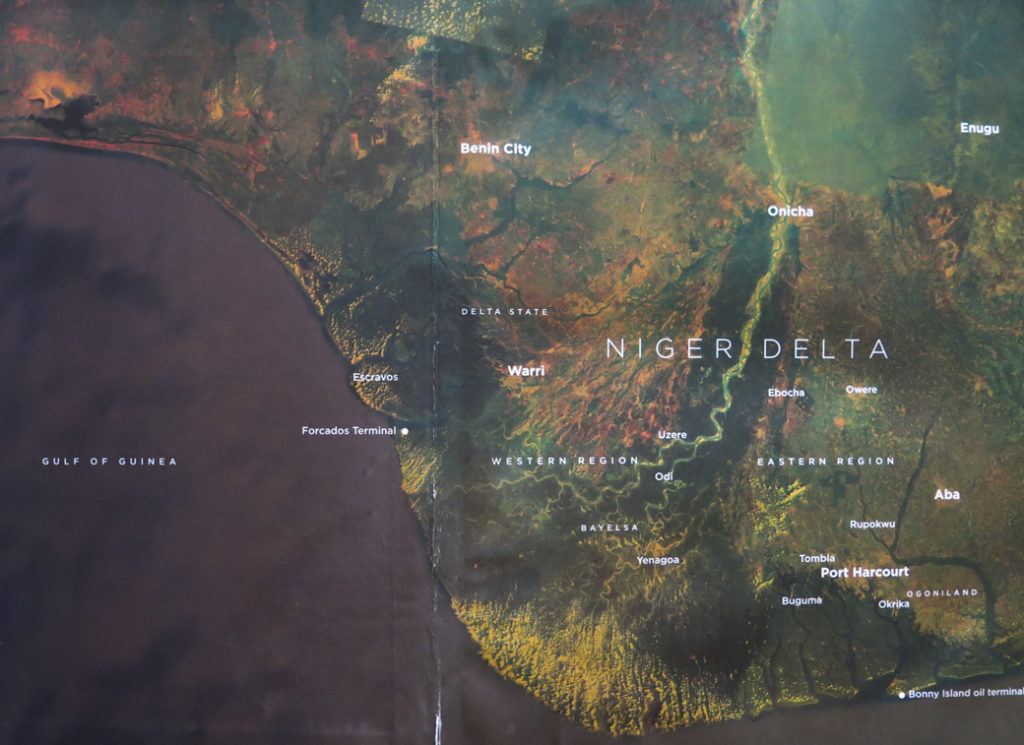

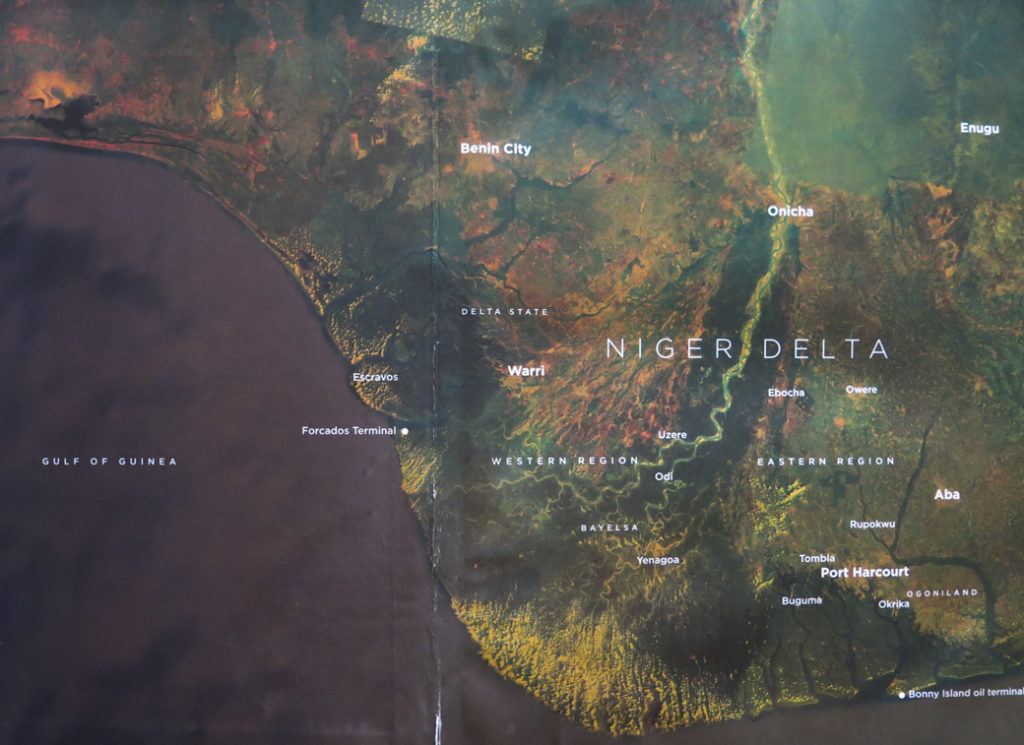

Then we come to the present in the domain of Chicoco Radio (actually, it’s more than radio, as you’ll see). This far-reaching organization is situated in the Okrika waterfront of Port Harcourt, a crowded warren of informal houses, at risk of being summarily bulldozed in the recent past, and home to dense communities of civil servants, students, bankers and tradespeople, as well as a robust criminal element ranging from ordinary street thugs, to venal and corrupt police and paramilitary, to “tappers” and “bunkerers”—that is, enterprising but unemployed locals who tempt fate by tapping into neglected oil pipelines, cooking their harvest, and selling it in barrels to boats and ships waiting just off the coast. All of this is the legacy of Shell Nigeria’s political and economic domination of the Niger Delta since oil was discovered there in 1956. Amid this legacy, the Chicoco community is working to create a new future, first mapping these neighborhoods to give them a sense of ownership, then to identify young people interested in learning a variety of skills: journalism, photography, music production and performance, radio arts and filmmaking.

That’s the broad outline. Now to the voices of those who live the Niger Delta reality...

REX LAWSON

[caption id="attachment_36322" align="aligncenter" width="471"] Rex Lawson[/caption]

Professor Onyee Nwankpa (Rex Lawson Chair University of Port Harcourt)

Well, the Rex Lawson Chair… Our Vice Chancellor is very much interested in music. In fact, his second name could be music. He is so in love, so passionate about music, he can go starving as long as you give him music. I don't think there is any university in Nigeria that will rank a close second in terms of what this university has done to endow chairs. So it was through his leadership that a chair was endowed in honor of an illustrious Niger Delta son, an illustrious Kalabari son, an illustrious Rivers State son: Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson.

Rex Lawson meant so much not only to the Nigerian populace but to the entire West African subregion. Rex Lawson sang many pieces in different languages, especially the Kalabari languages and Kalabari idioms. He was quite a visionary. Very creative, very innovative.

He also sang in Igbo language, in Efik language. In English of course. And also in one Ghanaian language. He was quite all over the place. And then also, when he went to Cameroon, he also sang in their language. He was quite diversified. Quite gifted.

Rex Lawson[/caption]

Professor Onyee Nwankpa (Rex Lawson Chair University of Port Harcourt)

Well, the Rex Lawson Chair… Our Vice Chancellor is very much interested in music. In fact, his second name could be music. He is so in love, so passionate about music, he can go starving as long as you give him music. I don't think there is any university in Nigeria that will rank a close second in terms of what this university has done to endow chairs. So it was through his leadership that a chair was endowed in honor of an illustrious Niger Delta son, an illustrious Kalabari son, an illustrious Rivers State son: Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson.

Rex Lawson meant so much not only to the Nigerian populace but to the entire West African subregion. Rex Lawson sang many pieces in different languages, especially the Kalabari languages and Kalabari idioms. He was quite a visionary. Very creative, very innovative.

He also sang in Igbo language, in Efik language. In English of course. And also in one Ghanaian language. He was quite all over the place. And then also, when he went to Cameroon, he also sang in their language. He was quite diversified. Quite gifted.

Rex Lawson was born in Buguma in Calabar in 1938. In primary school, he exhibited his interest in drumming and things like that, to marching bands in the school, and from there he got interested in singing and trumpet playing. He established bands here and there, and he moved. At that time in the eastern region, you could just move from one city to the other. From Port Harcourt, he went to Onitsha, to Enugu. He was just playing all over, even in Warri. Later on, it was at one of the invitations that he went to honor in Warri, at a place called Runny Bay, that he had an automobile accident and died. He died at the age of 33.

That was on January 16, 1971. But since, because of the impact that he had made, his impact and the philosophical gamut of his musical presentation and his religious inclination, made his fans give him names like Pastor, then from Pastor to Bishop, from Bishop to Archbishop, and very many places he was playing. And then finally, they branded him Cardinal. And that was his title until he died, Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson.

[caption id="attachment_36304" align="aligncenter" width="561"]

Rex Lawson was born in Buguma in Calabar in 1938. In primary school, he exhibited his interest in drumming and things like that, to marching bands in the school, and from there he got interested in singing and trumpet playing. He established bands here and there, and he moved. At that time in the eastern region, you could just move from one city to the other. From Port Harcourt, he went to Onitsha, to Enugu. He was just playing all over, even in Warri. Later on, it was at one of the invitations that he went to honor in Warri, at a place called Runny Bay, that he had an automobile accident and died. He died at the age of 33.

That was on January 16, 1971. But since, because of the impact that he had made, his impact and the philosophical gamut of his musical presentation and his religious inclination, made his fans give him names like Pastor, then from Pastor to Bishop, from Bishop to Archbishop, and very many places he was playing. And then finally, they branded him Cardinal. And that was his title until he died, Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson.

[caption id="attachment_36304" align="aligncenter" width="561"] Princess, Frederick and Kelvin: daughter, grandson and great grandson of Rex Lawson[/caption]

Princess Lawson (Rex’s eldest daughter) and Fredrick Lawson (Rex’s grandson, and a DJ today)

Princess: I was five when he died. I remember him coming home late in the night. And in the early hours of the morning, when I wake up from bed, he used to carry me on his shoulders, because he loved me very much. That's all I can remember. I used to think about him as a great man, because the kind of job he did. I don't think there is another person like him on his earth. He cannot be compared. So sometimes I feel bad because I feel like I was supposed to meet him, to know him more better. That vacuum is still there. The pain of not knowing my dad. At times I feel it.

Fredrick: A lot of people just heard the name Rex Lawson, but they don't know the mystery behind the man. He was born in a polygamist family, and from his own mother, all the children she gave birth to died. Five died.

Princess: The father refused to name him. He was afraid he would die also. The name that was given to him, was Ere Kosima, meaning in Kalabari language, "Don't give him a name. He is not worthy of any name." But he called himself Rex, while Lawson is the compound’s name.

Fredrick: His father refused to take care of him, so his mother gave him to the church. He grew up under a church. He left Buguma to continue his education at Bakama. That is where he learned to play the trumpet. So they did not see him for some time. They thought he was dead. Then he moved to Ghana, from Ghana to Cameroon, before coming back to Nigeria. When he came back to Nigeria, a lot of people did not understand where he was coming from, because of his language. All of this area was under the eastern region then. Calabar, or I will say the Niger Delta, was not known. We were under the eastern region. So a lot of people didn’t know that tribes named Kalabari and Ijaw existed. In time, they got to understand, due to the messages he sent across.

Whatever songs he's singing, there's a message. Like “Anah I Don Tire.” There is this Efik lady he was playing for at Calabar. She loved him. She didn't want to let him go. She just wanted to have him by her side. But he was fed up with everything that was happening and now had to leave. So he sang that song for Anah. “I'm going now. I want to go. I am tired of staying. That's it.” And “Sawale.” At that particular time, Rex found out that little girls had started going into prostitution and other things, so the message was that you don't sawa… Sawa is like something that has spoiled, has gone bad. That was just the message.

Princess: They call Rex a prophet. His music is always talking about the future, like revelation in the Bible. Like when he sang “Tom Kirisite” He was saying kids do not listen to their parents, and parents don't listen to their kids. He was saying God should come. This world is coming to another thing. And then “Tamuno Wenibo.” He was telling the people of the world that what kind of evil is in the world now. People are so much in evil that they do not even remember God again. He's asking God to come down and save the world.

Onyee Nwankpa: The religion there is usually ascribed not to Jesus and the Christian God, but in relationship to God the creator, and then other deities who are subservient to God. So the religion will be basically on moral implications of dealings with people and your neighbor. That's the kind of religiosity of his music. It's talking about you as a child of God. Not Christian, not Muslim. No, no. His music could not be a barrier, or an impediment to any other faith. No. It will not be an impediment. Because any faith will understand if it is a faith that is rooted in God and humanity.

[caption id="attachment_36311" align="alignright" width="316"]

Princess, Frederick and Kelvin: daughter, grandson and great grandson of Rex Lawson[/caption]

Princess Lawson (Rex’s eldest daughter) and Fredrick Lawson (Rex’s grandson, and a DJ today)

Princess: I was five when he died. I remember him coming home late in the night. And in the early hours of the morning, when I wake up from bed, he used to carry me on his shoulders, because he loved me very much. That's all I can remember. I used to think about him as a great man, because the kind of job he did. I don't think there is another person like him on his earth. He cannot be compared. So sometimes I feel bad because I feel like I was supposed to meet him, to know him more better. That vacuum is still there. The pain of not knowing my dad. At times I feel it.

Fredrick: A lot of people just heard the name Rex Lawson, but they don't know the mystery behind the man. He was born in a polygamist family, and from his own mother, all the children she gave birth to died. Five died.

Princess: The father refused to name him. He was afraid he would die also. The name that was given to him, was Ere Kosima, meaning in Kalabari language, "Don't give him a name. He is not worthy of any name." But he called himself Rex, while Lawson is the compound’s name.

Fredrick: His father refused to take care of him, so his mother gave him to the church. He grew up under a church. He left Buguma to continue his education at Bakama. That is where he learned to play the trumpet. So they did not see him for some time. They thought he was dead. Then he moved to Ghana, from Ghana to Cameroon, before coming back to Nigeria. When he came back to Nigeria, a lot of people did not understand where he was coming from, because of his language. All of this area was under the eastern region then. Calabar, or I will say the Niger Delta, was not known. We were under the eastern region. So a lot of people didn’t know that tribes named Kalabari and Ijaw existed. In time, they got to understand, due to the messages he sent across.

Whatever songs he's singing, there's a message. Like “Anah I Don Tire.” There is this Efik lady he was playing for at Calabar. She loved him. She didn't want to let him go. She just wanted to have him by her side. But he was fed up with everything that was happening and now had to leave. So he sang that song for Anah. “I'm going now. I want to go. I am tired of staying. That's it.” And “Sawale.” At that particular time, Rex found out that little girls had started going into prostitution and other things, so the message was that you don't sawa… Sawa is like something that has spoiled, has gone bad. That was just the message.

Princess: They call Rex a prophet. His music is always talking about the future, like revelation in the Bible. Like when he sang “Tom Kirisite” He was saying kids do not listen to their parents, and parents don't listen to their kids. He was saying God should come. This world is coming to another thing. And then “Tamuno Wenibo.” He was telling the people of the world that what kind of evil is in the world now. People are so much in evil that they do not even remember God again. He's asking God to come down and save the world.

Onyee Nwankpa: The religion there is usually ascribed not to Jesus and the Christian God, but in relationship to God the creator, and then other deities who are subservient to God. So the religion will be basically on moral implications of dealings with people and your neighbor. That's the kind of religiosity of his music. It's talking about you as a child of God. Not Christian, not Muslim. No, no. His music could not be a barrier, or an impediment to any other faith. No. It will not be an impediment. Because any faith will understand if it is a faith that is rooted in God and humanity.

[caption id="attachment_36311" align="alignright" width="316"] Professor Onyee Nwankpa (a more joyful Hip Deep scholar has not been found)[/caption]

This was the time of vinyl records and the gramophone. Thirty-three, 45 and 78 RPM. They were buying them. They were playing them. You would start a tune, before you know it everyone is singing. It was catching the popular appeal. And the music was talking about events of the society. You know, whether it's religious, cultural, virtuous, anything, morality. It was just picking every human folly. Every human concern. Every human issue. Social, political, religious, anything. Even human conditions. Like there is no condition that is permanent in this world. You can be a rich man today, tomorrow you become poor. You can be a poor man today, tomorrow you become rich. There is no condition that is permanent.

In Rex Lawson’s music, you will enjoy quite a lot of things. A variety of things. One will be his stage presentation. Two will be his trumpet motifs. Three will be the theme, the thematic structure, his melodies, and the simplicity of the melodies. Even when you do not know the song, you will just sing along, without really knowing what he's singing. And of course, the percussion, the section that he will reserve for just percussion only. Nothing else. The Western instruments will not play, just purely African instruments, percussion, and then the rest will come back to play the closing part.

[caption id="attachment_36314" align="alignleft" width="247"]

Professor Onyee Nwankpa (a more joyful Hip Deep scholar has not been found)[/caption]

This was the time of vinyl records and the gramophone. Thirty-three, 45 and 78 RPM. They were buying them. They were playing them. You would start a tune, before you know it everyone is singing. It was catching the popular appeal. And the music was talking about events of the society. You know, whether it's religious, cultural, virtuous, anything, morality. It was just picking every human folly. Every human concern. Every human issue. Social, political, religious, anything. Even human conditions. Like there is no condition that is permanent in this world. You can be a rich man today, tomorrow you become poor. You can be a poor man today, tomorrow you become rich. There is no condition that is permanent.

In Rex Lawson’s music, you will enjoy quite a lot of things. A variety of things. One will be his stage presentation. Two will be his trumpet motifs. Three will be the theme, the thematic structure, his melodies, and the simplicity of the melodies. Even when you do not know the song, you will just sing along, without really knowing what he's singing. And of course, the percussion, the section that he will reserve for just percussion only. Nothing else. The Western instruments will not play, just purely African instruments, percussion, and then the rest will come back to play the closing part.

[caption id="attachment_36314" align="alignleft" width="247"] Anthony Odili and guitarist before the Shed concert[/caption]

Anthony Odili (The last surviving member of Rex Lawson’s band)

They call me Papa Tony Odili because of my age. This year I just started my 90 years. I played music 69 years, and my age today, born January 3, Thursday, 11 o’clock, 1928. At 20, I left secondary school. I came from a very poor family. I was so young when my father died. He was even against me playing music, but my mother said, “My husband, leave your son. You don’t know his destiny.” And that is my destiny until today. I play drum set, play other instruments, but I decided to play this African percussion.

Sam Dede (Film actor, lecturer at University of Port Harcourt)

[caption id="attachment_36325" align="alignright" width="261"]

Anthony Odili and guitarist before the Shed concert[/caption]

Anthony Odili (The last surviving member of Rex Lawson’s band)

They call me Papa Tony Odili because of my age. This year I just started my 90 years. I played music 69 years, and my age today, born January 3, Thursday, 11 o’clock, 1928. At 20, I left secondary school. I came from a very poor family. I was so young when my father died. He was even against me playing music, but my mother said, “My husband, leave your son. You don’t know his destiny.” And that is my destiny until today. I play drum set, play other instruments, but I decided to play this African percussion.

Sam Dede (Film actor, lecturer at University of Port Harcourt)

[caption id="attachment_36325" align="alignright" width="261"] Sam Dede (Eyre 2017)[/caption]

Tony Odili was able to replicate what we call the ikriko. It's a wooden instrument, carved out of a tree trunk. Tony was able to replicate the message of ikriko with the three-tier drums. And it is such a delight to watch him play, and to listen to him. He sounds anew every day. Because the ikriko is more or less what is used as a means of announcing events. For instance, if there's the death of a big chief, you first hear from the ikriko. Once they play his traditional name, you hear from afar, you know the man has passed on.

Onyee Nwankpa: Here in Nigeria, and all over Africa, music is used for various events, from birth to death. Whether it is church activity, social activity, name-giving ceremonies, birthday ceremonies, or climate or cultural season of the year. For instance the farming season and the harvesting season, these are some of the events and seasons in the year that would all have music that go to celebrate them. And so, as a child, you were naturally involved in music making, participating one way or the other. So that is how Rex Lawson got involved.

Anthony Odili: Rex was gifted. He picked us and we were blessed musicians. Faithful musicians. Truthful musicians. But today, my colleagues are all late. I am the only man living. I am not happy that I am living, but we all were not born on the same day. We will not die the same day. We don’t do rehearsal. One thing with Rex, he likes to buy schnapps. British. No beer or Nigeria drink. He will start to sing. He will now call the rhythm guitarist. “I am singing. Just back me.” He teaches everybody their own part. This is how we do our records. He’s a gifted man. Take it from me. I’ve not seen any bandleader like Rex Lawson in my life. Seventy years I played that conga: nobody like Rex Lawson.

[caption id="attachment_36328" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Sam Dede (Eyre 2017)[/caption]

Tony Odili was able to replicate what we call the ikriko. It's a wooden instrument, carved out of a tree trunk. Tony was able to replicate the message of ikriko with the three-tier drums. And it is such a delight to watch him play, and to listen to him. He sounds anew every day. Because the ikriko is more or less what is used as a means of announcing events. For instance, if there's the death of a big chief, you first hear from the ikriko. Once they play his traditional name, you hear from afar, you know the man has passed on.

Onyee Nwankpa: Here in Nigeria, and all over Africa, music is used for various events, from birth to death. Whether it is church activity, social activity, name-giving ceremonies, birthday ceremonies, or climate or cultural season of the year. For instance the farming season and the harvesting season, these are some of the events and seasons in the year that would all have music that go to celebrate them. And so, as a child, you were naturally involved in music making, participating one way or the other. So that is how Rex Lawson got involved.

Anthony Odili: Rex was gifted. He picked us and we were blessed musicians. Faithful musicians. Truthful musicians. But today, my colleagues are all late. I am the only man living. I am not happy that I am living, but we all were not born on the same day. We will not die the same day. We don’t do rehearsal. One thing with Rex, he likes to buy schnapps. British. No beer or Nigeria drink. He will start to sing. He will now call the rhythm guitarist. “I am singing. Just back me.” He teaches everybody their own part. This is how we do our records. He’s a gifted man. Take it from me. I’ve not seen any bandleader like Rex Lawson in my life. Seventy years I played that conga: nobody like Rex Lawson.

[caption id="attachment_36328" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Staff & students at noontime gig with department band, in highlife mode![/caption]

Onyee Nwankpa: When Rex Lawson died, I was still a little boy living a little bit far away from what he was doing here. But I knew his band was still playing. What happened was he was invited to come and play in the city of Warri. But he did not leave early, and the express roads we now have was not there at the time. So going to Warri was a much longer journey.

He had sent his band members ahead, and the big guy was coming behind. He left very late in the evening. I think the record was that he left after 6 p.m., and he made a few stops. He stopped at Aba, bought some materials, some clothing. Stopped at Onitsha. Stopped at Abo for food. The food that was presented to him wasn't his kind of food and he got scared. He abandoned the food. But along the way, they were buying a lot of drinks. So they were getting drunk and high and going very late. So they slept off, leaving the driver alone. And so, at a base called Urhomigbe, the vehicle had an accident. It ran off the road and hit a palm tree. The front glass got broken and a piece of that got lodged into his brain. The others survived. He was the only one who died. He was in the front seat. So by the time they took him to the Eku Hospital, he was pronounced dead.

And that's how he died. His death shocked the whole state, the whole nation. Everyone was plunged into deep mourning. He was given a state burial under the leadership of then governor of Rivers State.

Sam Dede: The music of Rex Lawson will never leave the mindset of our people here. Because he was the first musician who sang about the social life of people around here.

Frederick: if you talk about popular performance in Nigeria today, if the artist is performing on stage, before he has performed 10 songs, you find out that eight of the songs are from Rex Lawson. Yes. Go around nightclubs, wherever you see live events. If the artist is performing five songs, three must come from Rex Lawson. So right now we are trying to see how we can make upcoming musicians know this great man, and for them to remix his songs into modern dance feel. Just like what they did for the late Bob Marley. I heard some of his work featuring artists like Lauryn Hill, the Lost Boys. They made those reggae tunes into modern dance style of music. We are thinking of doing things like that, merging modern music artists with the highlife tunes. That's what we’re trying to do.

[caption id="attachment_36310" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

Staff & students at noontime gig with department band, in highlife mode![/caption]

Onyee Nwankpa: When Rex Lawson died, I was still a little boy living a little bit far away from what he was doing here. But I knew his band was still playing. What happened was he was invited to come and play in the city of Warri. But he did not leave early, and the express roads we now have was not there at the time. So going to Warri was a much longer journey.

He had sent his band members ahead, and the big guy was coming behind. He left very late in the evening. I think the record was that he left after 6 p.m., and he made a few stops. He stopped at Aba, bought some materials, some clothing. Stopped at Onitsha. Stopped at Abo for food. The food that was presented to him wasn't his kind of food and he got scared. He abandoned the food. But along the way, they were buying a lot of drinks. So they were getting drunk and high and going very late. So they slept off, leaving the driver alone. And so, at a base called Urhomigbe, the vehicle had an accident. It ran off the road and hit a palm tree. The front glass got broken and a piece of that got lodged into his brain. The others survived. He was the only one who died. He was in the front seat. So by the time they took him to the Eku Hospital, he was pronounced dead.

And that's how he died. His death shocked the whole state, the whole nation. Everyone was plunged into deep mourning. He was given a state burial under the leadership of then governor of Rivers State.

Sam Dede: The music of Rex Lawson will never leave the mindset of our people here. Because he was the first musician who sang about the social life of people around here.

Frederick: if you talk about popular performance in Nigeria today, if the artist is performing on stage, before he has performed 10 songs, you find out that eight of the songs are from Rex Lawson. Yes. Go around nightclubs, wherever you see live events. If the artist is performing five songs, three must come from Rex Lawson. So right now we are trying to see how we can make upcoming musicians know this great man, and for them to remix his songs into modern dance feel. Just like what they did for the late Bob Marley. I heard some of his work featuring artists like Lauryn Hill, the Lost Boys. They made those reggae tunes into modern dance style of music. We are thinking of doing things like that, merging modern music artists with the highlife tunes. That's what we’re trying to do.

[caption id="attachment_36310" align="aligncenter" width="502"] Onyee Nwanpa in Music Department at UNIPORT[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36327" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Onyee Nwanpa in Music Department at UNIPORT[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36327" align="aligncenter" width="640"] UNIPORT Music Dept. with Banning and Mark[/caption]

THE BIAFRAN WAR

This is a sensitive and complex topic. For more on our research into the war, see our interview with historian Mark LeVine. What follows are some personal and musical reminiscences and insights from some of the people we met in the Niger Delta.

Howells G (Musician and part of the Chicoco family): Well, my grandfather would say, "When two people are disagreeing, be careful.” If you meet Mr. A and he tells you his own story, and you feel like taking your machete and striking Mr. B. See Mr. B before you carry your machete. You might feel like taking your machete to go back and strike Mr. A. Everyone tells the story to suit his own. Until the animals begin to write their own book, the hunter will be the greatest. You never read the book of the animals.

Sam Dede: There's a part of the West Coast that is referred to as Biafra, the Bight of Biafra.

Banning: So the word was in existence before that struggle. And it's still there.

Onyee Nwankpa: The Biafra War is an area that really touches one's emotions. But I will try and see how best we can handle it. My first comment on this is that war is not a good thing. It doesn't do any good to any society. War comes with a lot of killing, maiming, destruction. The Nigerian Biafra War was called by some people a war of genocide. To some, it was a war to keep Nigeria one. To some, it was a war of liberation, a war to preserve certain religion, that was the Christian religion. To some people, they would say that it was a war for the Igbos, that the Igbos wanted to secede.

I was a little boy at the time. And so the war really dealt with me, and with my family. And that's why I say it's a little bit of an emotional thing. My town Umuagbai Ndoki had to fall to the Vandals at the time; we call them the Vandals. Our area fell in early 1968, and so we left. I had never experienced war. My parents said, "Come, come, come, come,” and we ran out with whatever we were putting on. For the rest of two years we were on the move. We were in refugee camps.

Frank A.O. Ugiomoh (Professor of Art History at the University of Port Harcourt): I was 12 then. I was in Aba (a town in the Delta), before Biafra had come to be. The Igbos came to the Choba River and said, "Any fish you catch is Biafran fish, and nothing more, not even for you in the festivals you used to relish in." And then, the minorities were asking, "What is our place in this new and growing configuration called Biafra?" They said, "Don't worry. By the time we win the war, they will give you your place."

You just have the assurance that your neighbor is not going to dominate you, and then he is carrying out some policies that pointed to the fact that he is probably going to undermine you as soon as he gets there. Like the overrunning of the Choba Fish Festival and all of that. So those are some of the fears the minorities had during the war.

Howells G: In Rivers State, you move a little, and you get another language. You see, in the riverine area, we all came from another part of the country. I'm from Okrika. But we actually migrated from a part of Bayelsa. Even our talking drum, if you listen well to the talking drum, you hear something of other tribes, because when our forefathers in Okrika, they came down with that part of language and culture.

Sam Dede: More than anything else, I think [the war] was about ethnicity. Yeah, it was about ethnicity. The Biafra struggle was already on, but full-scale war had not been declared dead. And then Isaac Adako Boro went out to tell the world, "We have a different agitation. What we are fighting for is to control our resources. We will provide the oil that the entire country is getting fat on. We would like to control these resources ourselves.” That was before the Biafra War was even declared. So it’s not like oil did not play a role in it. The oil was a major factor. But ethnicity was the driving force of the Biafra War.

Frank Ugiomoh: It's really difficult to say where the starting point is. But the Igbo man who was always the first to cry hard and loud, never tells the story of what happened before. He tells the story of how he was gunned down. But he never tells the story of his complicity in the whole complex narrative that led to the war.

One of my colleagues, Dr. Tido Niang, in the graphics department at my university, did his PhD on the Nigerian Civil War, specifically on the posters and ephemera of the war. When he came here to Port Harcourt for the first experience, he got to the War Museum and saw that it was all machinery and nothing else. But the machinery is not the war in itself. The ephemera that went with the war are more important to the narrative of the war than what was shown in the museum. So Tido has collected a whole lot of posters stamps, currencies, cartoons and songs.

He came to the conclusion that the Nigerian Biafra War had nothing to do with oil, but it was just an elitist contestation. It was a war simply fashioned within the framework of elitism amongst Nigerians. The elites of the nation, from the North and the South and the West. It was their egos that the war funded, and nothing more than that.

UNIPORT Music Dept. with Banning and Mark[/caption]

THE BIAFRAN WAR

This is a sensitive and complex topic. For more on our research into the war, see our interview with historian Mark LeVine. What follows are some personal and musical reminiscences and insights from some of the people we met in the Niger Delta.

Howells G (Musician and part of the Chicoco family): Well, my grandfather would say, "When two people are disagreeing, be careful.” If you meet Mr. A and he tells you his own story, and you feel like taking your machete and striking Mr. B. See Mr. B before you carry your machete. You might feel like taking your machete to go back and strike Mr. A. Everyone tells the story to suit his own. Until the animals begin to write their own book, the hunter will be the greatest. You never read the book of the animals.

Sam Dede: There's a part of the West Coast that is referred to as Biafra, the Bight of Biafra.

Banning: So the word was in existence before that struggle. And it's still there.

Onyee Nwankpa: The Biafra War is an area that really touches one's emotions. But I will try and see how best we can handle it. My first comment on this is that war is not a good thing. It doesn't do any good to any society. War comes with a lot of killing, maiming, destruction. The Nigerian Biafra War was called by some people a war of genocide. To some, it was a war to keep Nigeria one. To some, it was a war of liberation, a war to preserve certain religion, that was the Christian religion. To some people, they would say that it was a war for the Igbos, that the Igbos wanted to secede.

I was a little boy at the time. And so the war really dealt with me, and with my family. And that's why I say it's a little bit of an emotional thing. My town Umuagbai Ndoki had to fall to the Vandals at the time; we call them the Vandals. Our area fell in early 1968, and so we left. I had never experienced war. My parents said, "Come, come, come, come,” and we ran out with whatever we were putting on. For the rest of two years we were on the move. We were in refugee camps.

Frank A.O. Ugiomoh (Professor of Art History at the University of Port Harcourt): I was 12 then. I was in Aba (a town in the Delta), before Biafra had come to be. The Igbos came to the Choba River and said, "Any fish you catch is Biafran fish, and nothing more, not even for you in the festivals you used to relish in." And then, the minorities were asking, "What is our place in this new and growing configuration called Biafra?" They said, "Don't worry. By the time we win the war, they will give you your place."

You just have the assurance that your neighbor is not going to dominate you, and then he is carrying out some policies that pointed to the fact that he is probably going to undermine you as soon as he gets there. Like the overrunning of the Choba Fish Festival and all of that. So those are some of the fears the minorities had during the war.

Howells G: In Rivers State, you move a little, and you get another language. You see, in the riverine area, we all came from another part of the country. I'm from Okrika. But we actually migrated from a part of Bayelsa. Even our talking drum, if you listen well to the talking drum, you hear something of other tribes, because when our forefathers in Okrika, they came down with that part of language and culture.

Sam Dede: More than anything else, I think [the war] was about ethnicity. Yeah, it was about ethnicity. The Biafra struggle was already on, but full-scale war had not been declared dead. And then Isaac Adako Boro went out to tell the world, "We have a different agitation. What we are fighting for is to control our resources. We will provide the oil that the entire country is getting fat on. We would like to control these resources ourselves.” That was before the Biafra War was even declared. So it’s not like oil did not play a role in it. The oil was a major factor. But ethnicity was the driving force of the Biafra War.

Frank Ugiomoh: It's really difficult to say where the starting point is. But the Igbo man who was always the first to cry hard and loud, never tells the story of what happened before. He tells the story of how he was gunned down. But he never tells the story of his complicity in the whole complex narrative that led to the war.

One of my colleagues, Dr. Tido Niang, in the graphics department at my university, did his PhD on the Nigerian Civil War, specifically on the posters and ephemera of the war. When he came here to Port Harcourt for the first experience, he got to the War Museum and saw that it was all machinery and nothing else. But the machinery is not the war in itself. The ephemera that went with the war are more important to the narrative of the war than what was shown in the museum. So Tido has collected a whole lot of posters stamps, currencies, cartoons and songs.

He came to the conclusion that the Nigerian Biafra War had nothing to do with oil, but it was just an elitist contestation. It was a war simply fashioned within the framework of elitism amongst Nigerians. The elites of the nation, from the North and the South and the West. It was their egos that the war funded, and nothing more than that.

Onyee Nwankpa: But let's go back. The war came as a result of the coup that took place first in 1966, January. There was a coup that took place that ousted the government of Zik and Abubakar Balewa. And that coup claimed the lives of some of the premiers. Because at that time, Nigeria was divided into regions, the Eastern region, the Western region, Midwestern region, and Northern region. So that was what happened. Some premiers were killed.

Some people took that uprising as something that was masterminded by the Easterners. But it was just a few majors who wanted to stop the wrong governance, bad governments of Nigeria—something that has not left us until today, unfortunately. The corrupt practices and so on and so forth – they really wanted to stem that tide. But at the same time, it was not properly interpreted. And so the Northerners went after the Easterners. Predominantly the Igbos. And there was a pogrom. They killed them. Maimed them. In the north.

The military governor of Eastern Nigeria was Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu. He was in charge and he did everything to try to stop the killing of the Easterners in the north. But the central government at the time did not do anything to stem this tide of the killing. And then Ojukwu said, "Well, if we don't feel secure in our own country, maybe it would be the best, in our best interest, to now ask for a different country where we can protect the indigenous people of the country." Then, one thing led to the other, and to the Republic of Biafra. So the idea was proposed as an alternative to this killing.

As I told you, there were so many reasons. But we also know that the eastern half of this country is the treasure base of the nation. With oil and all the natural resources here, losing this enclave would mean losing so much money. And so they said, “Uh uh, you must be part of us. We must have that land. By hook or by crook." And so they engage them, by hook, and by crook. Yes. They engaged with all kinds of military warfare and starvation. At that time people were dying at the hands of the Nigerians, the Vandals started bombing people in their churches, marketplaces, any place they see a collection of people, they will just kill them.

Anthony Odili: During the war, it was terrible. If you were to be a Nigerian, you would run away and leave your children and your wife to save your head. We should not go back to the past. Today, I’m hearing some boys say, “Hey, Biafra, Biafra.” They were not born. They only heard. May Christ forgive them. They should go back and ask their living grandfathers. Let their grandfathers advise them. Those who saw the war will never pray for the war to come back.

[caption id="attachment_36313" align="aligncenter" width="583"]

Onyee Nwankpa: But let's go back. The war came as a result of the coup that took place first in 1966, January. There was a coup that took place that ousted the government of Zik and Abubakar Balewa. And that coup claimed the lives of some of the premiers. Because at that time, Nigeria was divided into regions, the Eastern region, the Western region, Midwestern region, and Northern region. So that was what happened. Some premiers were killed.

Some people took that uprising as something that was masterminded by the Easterners. But it was just a few majors who wanted to stop the wrong governance, bad governments of Nigeria—something that has not left us until today, unfortunately. The corrupt practices and so on and so forth – they really wanted to stem that tide. But at the same time, it was not properly interpreted. And so the Northerners went after the Easterners. Predominantly the Igbos. And there was a pogrom. They killed them. Maimed them. In the north.

The military governor of Eastern Nigeria was Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu. He was in charge and he did everything to try to stop the killing of the Easterners in the north. But the central government at the time did not do anything to stem this tide of the killing. And then Ojukwu said, "Well, if we don't feel secure in our own country, maybe it would be the best, in our best interest, to now ask for a different country where we can protect the indigenous people of the country." Then, one thing led to the other, and to the Republic of Biafra. So the idea was proposed as an alternative to this killing.

As I told you, there were so many reasons. But we also know that the eastern half of this country is the treasure base of the nation. With oil and all the natural resources here, losing this enclave would mean losing so much money. And so they said, “Uh uh, you must be part of us. We must have that land. By hook or by crook." And so they engage them, by hook, and by crook. Yes. They engaged with all kinds of military warfare and starvation. At that time people were dying at the hands of the Nigerians, the Vandals started bombing people in their churches, marketplaces, any place they see a collection of people, they will just kill them.

Anthony Odili: During the war, it was terrible. If you were to be a Nigerian, you would run away and leave your children and your wife to save your head. We should not go back to the past. Today, I’m hearing some boys say, “Hey, Biafra, Biafra.” They were not born. They only heard. May Christ forgive them. They should go back and ask their living grandfathers. Let their grandfathers advise them. Those who saw the war will never pray for the war to come back.

[caption id="attachment_36313" align="aligncenter" width="583"] Anthony Odili and Banning Eyre[/caption]

Sam Dede: In order to break the ranks of Biafra, the federal government created new states. One of those states was Rivers State. That will be 50 years this year, in May. The state government is planning all sorts of activities, for us, who are conscious of that event, we also mark the 50th anniversary of what we called the 12-day revolution, started by Isaac Adaka Boro. Isaac Boro Led the first violent revolution of the Niger Delta people against the Nigerian Republic. That was 1967. And that was effectively the start of the Biafra War.

Frank Ugiomoh: Gowon [the Nigerian president] cashed in on the situation, knowing that one way to break the Biafran tragedy for Nigeria was simply to grant these minorities their own state, and so they have a sense that they can take care of their destiny. So he created the state immediately to give these people a sense of belonging. “Oh, our brothers who asked us to join the war didn't give us anything of that nature." Divide and rule, you know. And often times, I joke with my fellow Nigerians that the Igbos live encircled within what I call hostile minorities. Yet they are the ones who would have the courage to say I would break away. But the Yorubas, who have two international boundaries unadulterated, they don't have any such ambition or agenda.

Howells G: My father told me some of these houses in Port Harcourt were owned by the Biafrans, the Igbo men. And he said, "At that time, even though the Biafrans were still fighting for sovereignty, they were already enslaving others.” This is part of why they lost in the Biafran civil war.

I think it's good the Biafrans should fight for their cause, but another thing that is missing is the map. The Biafran map. There are a lot of people there who are not involved not in the Biafran philosophy or struggle. Rivers State is in the Biafran map, but if the average Rivers man is not in the Biafran struggle. All these people they are shooting, they are not Rivers people. So they want to demonstrate, they will come to Rivers State and demonstrate, but they are Igbos. Where are the Ijaw? We are talking about the Niger Delta struggle, but is it synchronized with the Biafra struggle? No. It is not synchronized. Where are the Akwaybom people from Kosova State and other states in the Delta? So the Biafran struggle is somehow distorted.

The Bight of Biafra is south, south, close to the Atlantic Ocean, near the Bony River. And then the Igbos. Are they close to that river? Do they have connection with that river? They do not. So they should leave the name Biafra and try another name. So there's nothing wrong with the Biafran struggle, but they should make it properly.

[caption id="attachment_36329" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

Anthony Odili and Banning Eyre[/caption]

Sam Dede: In order to break the ranks of Biafra, the federal government created new states. One of those states was Rivers State. That will be 50 years this year, in May. The state government is planning all sorts of activities, for us, who are conscious of that event, we also mark the 50th anniversary of what we called the 12-day revolution, started by Isaac Adaka Boro. Isaac Boro Led the first violent revolution of the Niger Delta people against the Nigerian Republic. That was 1967. And that was effectively the start of the Biafra War.

Frank Ugiomoh: Gowon [the Nigerian president] cashed in on the situation, knowing that one way to break the Biafran tragedy for Nigeria was simply to grant these minorities their own state, and so they have a sense that they can take care of their destiny. So he created the state immediately to give these people a sense of belonging. “Oh, our brothers who asked us to join the war didn't give us anything of that nature." Divide and rule, you know. And often times, I joke with my fellow Nigerians that the Igbos live encircled within what I call hostile minorities. Yet they are the ones who would have the courage to say I would break away. But the Yorubas, who have two international boundaries unadulterated, they don't have any such ambition or agenda.

Howells G: My father told me some of these houses in Port Harcourt were owned by the Biafrans, the Igbo men. And he said, "At that time, even though the Biafrans were still fighting for sovereignty, they were already enslaving others.” This is part of why they lost in the Biafran civil war.

I think it's good the Biafrans should fight for their cause, but another thing that is missing is the map. The Biafran map. There are a lot of people there who are not involved not in the Biafran philosophy or struggle. Rivers State is in the Biafran map, but if the average Rivers man is not in the Biafran struggle. All these people they are shooting, they are not Rivers people. So they want to demonstrate, they will come to Rivers State and demonstrate, but they are Igbos. Where are the Ijaw? We are talking about the Niger Delta struggle, but is it synchronized with the Biafra struggle? No. It is not synchronized. Where are the Akwaybom people from Kosova State and other states in the Delta? So the Biafran struggle is somehow distorted.

The Bight of Biafra is south, south, close to the Atlantic Ocean, near the Bony River. And then the Igbos. Are they close to that river? Do they have connection with that river? They do not. So they should leave the name Biafra and try another name. So there's nothing wrong with the Biafran struggle, but they should make it properly.

[caption id="attachment_36329" align="aligncenter" width="502"] Howells G, Port Harcourt singer/songwriter and member of the Chicoco family[/caption]

Onyee Nwankpa: Rex Lawson was a little bit of the Biafran, but he withdrew into the Vandals, the Nigerian side. He withdrew when Port Harcourt was "liberated" by the federal might. So he returned to his space and so on. When he was on the side of Biafra, he played a highlife song that was called "Hail Biafra." But when he now returned, and came to the side of Nigeria, he played a piece dedicated to Gowon, at that time, the head of state. “Gowon Special.”

I think he knew that Nigeria was going to win the war. The second thing is that his place had been liberated, or conquered by the Nigerian forces. His home had been liberated. So is now time for him to come home to his kith and kin.

[caption id="attachment_36309" align="aligncenter" width="553"]

Howells G, Port Harcourt singer/songwriter and member of the Chicoco family[/caption]

Onyee Nwankpa: Rex Lawson was a little bit of the Biafran, but he withdrew into the Vandals, the Nigerian side. He withdrew when Port Harcourt was "liberated" by the federal might. So he returned to his space and so on. When he was on the side of Biafra, he played a highlife song that was called "Hail Biafra." But when he now returned, and came to the side of Nigeria, he played a piece dedicated to Gowon, at that time, the head of state. “Gowon Special.”

I think he knew that Nigeria was going to win the war. The second thing is that his place had been liberated, or conquered by the Nigerian forces. His home had been liberated. So is now time for him to come home to his kith and kin.

[caption id="attachment_36309" align="aligncenter" width="553"] Michael Uwemedimo and Ana Bonaldo (Eyre 2017)[/caption]

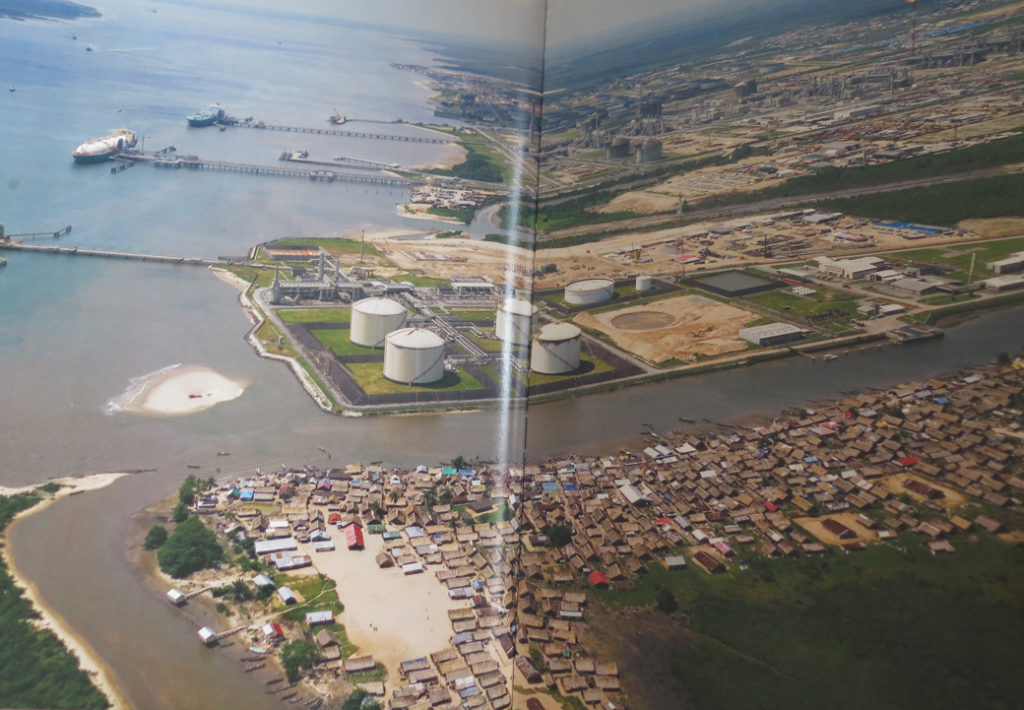

PORT HARCOURT TODAY: THE CHICOCO EXPERIENCE

Michael Uwemedimo (Directs Chicoco and C-Mapping with Ana Bonaldo): I grew up in Nigeria. Went to my mother’s school. My mother was English, but moved over here when she was 22 with my father who was Nigerian. I came back here originally in 2009 to make a film called Flow, which was going to start on an offshore rig and trace a pipeline through the country. While I was out here in preproduction for that and shooting some footage in the Western Delta, Amnesty International called and asked if I would make film for them on forced evictions in Port Harcourt. We had maybe 49 waterfronts around the city, nearly half a million people live in them, and all of them were declared for demolition in 2009.

Governor Amaechi (Leader of Rivers State in 2009): “When I am coming, mobile men will be there with their guns; policeman will be there with their gun; Army will bring their own; Air Force will bring their own; Navy will bring their own for me to go and take back my land.”

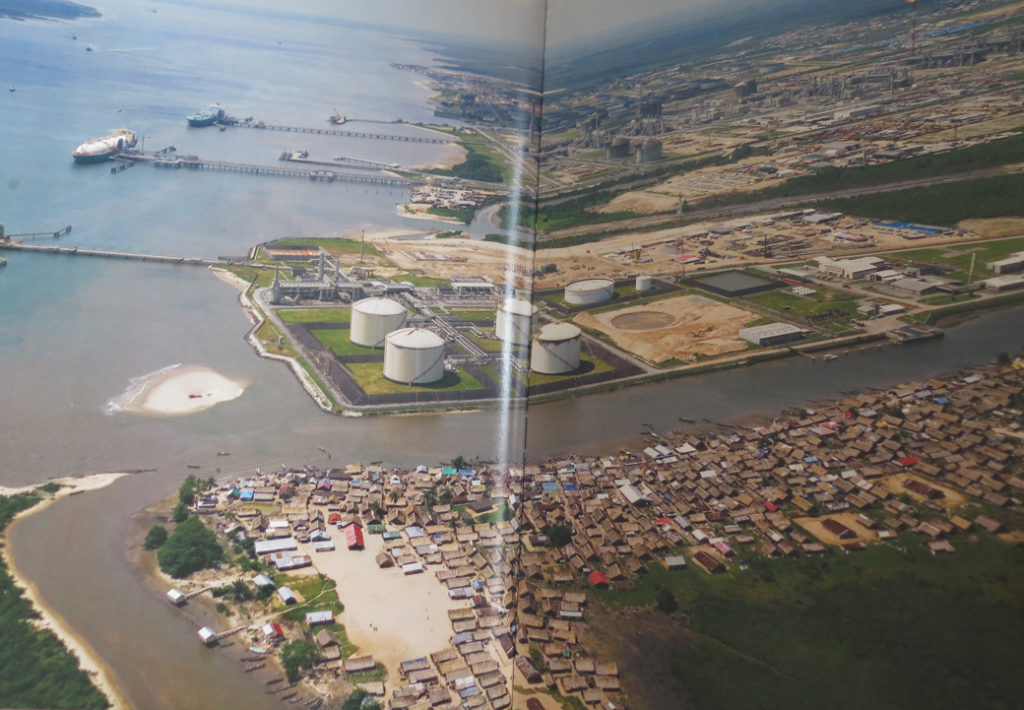

Michael: Port Harcourt is a colonial artifact. It was the city made to extract coal from the interior, from Enugu. A railway terminus was built, and there's a deep seaport. This area, the Bight of Benin, has been part of and international economy for 500 years that is trafficking darks cargo, first human beings, then palm oil, then coal, and now sweet, light crude oil.

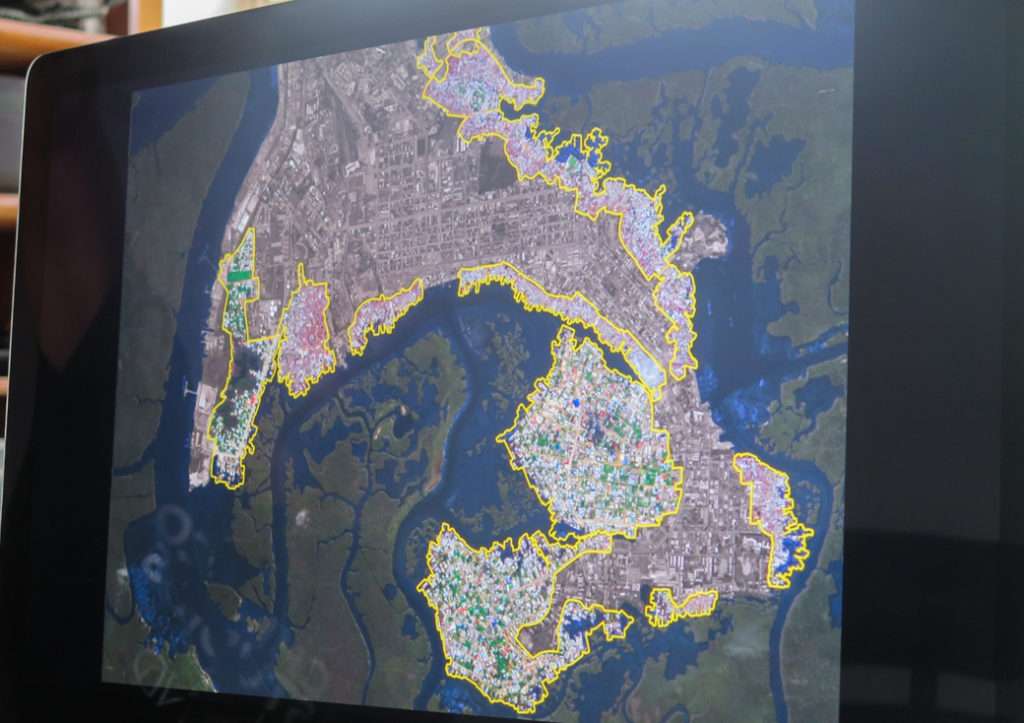

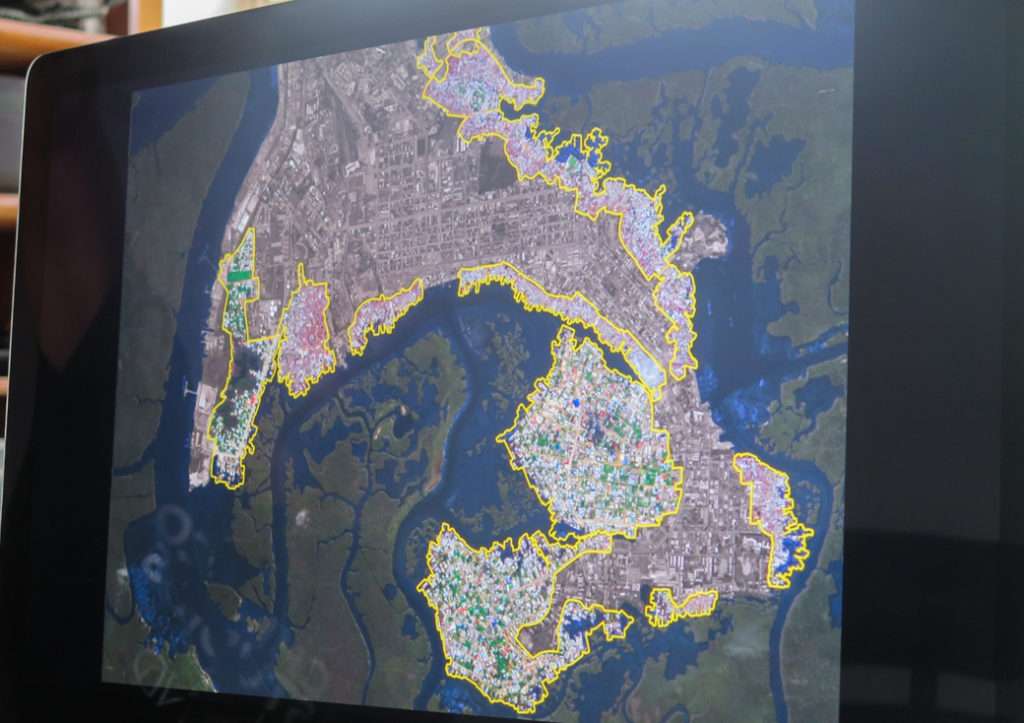

The violence, the material violence of extraction, and the social violence of segregation is inscribed in the plan of the original city. [Showing us a map] So this is the native quarters, the squat, tight barracks that were made for the junior civil servants and for the police and for the workers, the local workers. And this is where we are now, the old European quarter, the old Government Reserves Area, with its setbacks and leafy lawns.

Michael Uwemedimo and Ana Bonaldo (Eyre 2017)[/caption]

PORT HARCOURT TODAY: THE CHICOCO EXPERIENCE

Michael Uwemedimo (Directs Chicoco and C-Mapping with Ana Bonaldo): I grew up in Nigeria. Went to my mother’s school. My mother was English, but moved over here when she was 22 with my father who was Nigerian. I came back here originally in 2009 to make a film called Flow, which was going to start on an offshore rig and trace a pipeline through the country. While I was out here in preproduction for that and shooting some footage in the Western Delta, Amnesty International called and asked if I would make film for them on forced evictions in Port Harcourt. We had maybe 49 waterfronts around the city, nearly half a million people live in them, and all of them were declared for demolition in 2009.

Governor Amaechi (Leader of Rivers State in 2009): “When I am coming, mobile men will be there with their guns; policeman will be there with their gun; Army will bring their own; Air Force will bring their own; Navy will bring their own for me to go and take back my land.”

Michael: Port Harcourt is a colonial artifact. It was the city made to extract coal from the interior, from Enugu. A railway terminus was built, and there's a deep seaport. This area, the Bight of Benin, has been part of and international economy for 500 years that is trafficking darks cargo, first human beings, then palm oil, then coal, and now sweet, light crude oil.

The violence, the material violence of extraction, and the social violence of segregation is inscribed in the plan of the original city. [Showing us a map] So this is the native quarters, the squat, tight barracks that were made for the junior civil servants and for the police and for the workers, the local workers. And this is where we are now, the old European quarter, the old Government Reserves Area, with its setbacks and leafy lawns.

This is a map from an archive in the Netherlands ostensibly drawn by a department of a newly independent Nigerian agency, the director of the geographical survey in 1962. But if

you look in the other corner of the legend, you can see that it was compiled from air and ground surveys by Shell-BP Petroleum Development Company. So the map of Port Harcourt is literally drawn by Shell.

Port Harcourt is a city in the creeks, and along all the creeks that fringe the city, you have these very dense waterfront settlements. Ninety thousand people live here. You recognize this grid pattern, these very dense patterns. And these are all built on chicoco mud, sand fills and rubbish fills and mud fills. Chicoco mud is the fibrous mud from the mangroves. It's very dense and loamy. And people travel with canoes into the mangrove, and they cut it into blocks, and they pile their canoes with you, and then they bring it back to shore, and they use it to polder. And over years, they pack it, let it settle, pack it, let it settle, and then they build on it.

Mark LeVine (U.C. Irvine historian): We can’t call these settlements slums. In the U.S., slums are where really poor people live, but this is middle class, working middle class. People are civil servants, teachers in the universities. This is not absolute poverty.

Sam Dede: If you know the number of people who reside in these waterfronts, it is amazing. Really, really amazing. Those people go from those places to work in elite places like banks. They have nowhere else to live. They live in the waterfront, in those ramshackle shanties.

Michael: Yes, People have jobs and lives. But let me clarify something myself. The mass destruction of these neighborhoods, this bulldozing that we documented in 2008-2009, led to new informal settlements. That is both what was destroyed and what they went into. So that’s the point. Slum clearance is slum creation. It's a cycle. And it's a violent one.

This is a map from an archive in the Netherlands ostensibly drawn by a department of a newly independent Nigerian agency, the director of the geographical survey in 1962. But if

you look in the other corner of the legend, you can see that it was compiled from air and ground surveys by Shell-BP Petroleum Development Company. So the map of Port Harcourt is literally drawn by Shell.

Port Harcourt is a city in the creeks, and along all the creeks that fringe the city, you have these very dense waterfront settlements. Ninety thousand people live here. You recognize this grid pattern, these very dense patterns. And these are all built on chicoco mud, sand fills and rubbish fills and mud fills. Chicoco mud is the fibrous mud from the mangroves. It's very dense and loamy. And people travel with canoes into the mangrove, and they cut it into blocks, and they pile their canoes with you, and then they bring it back to shore, and they use it to polder. And over years, they pack it, let it settle, pack it, let it settle, and then they build on it.

Mark LeVine (U.C. Irvine historian): We can’t call these settlements slums. In the U.S., slums are where really poor people live, but this is middle class, working middle class. People are civil servants, teachers in the universities. This is not absolute poverty.

Sam Dede: If you know the number of people who reside in these waterfronts, it is amazing. Really, really amazing. Those people go from those places to work in elite places like banks. They have nowhere else to live. They live in the waterfront, in those ramshackle shanties.

Michael: Yes, People have jobs and lives. But let me clarify something myself. The mass destruction of these neighborhoods, this bulldozing that we documented in 2008-2009, led to new informal settlements. That is both what was destroyed and what they went into. So that’s the point. Slum clearance is slum creation. It's a cycle. And it's a violent one.

[Michael decided to stay in Port Harcourt as a filmmaker and activist, documenting abuses by the government and subsequent demonstrations, and raising consciousness through a movement called People Live Here. He and Ana created an initiative called C-Mapping, literally engaging local communities to map their streets and people to give them a sense of ownership. Michael said, “These communities were not part of the city's development plan. They were not on the map. And we wanted to give communities power to literally put themselves on the map.” That effort continues, but it also led to a more expansive idea: Chicoco.]

Michael: The idea was to let people into this space. We wondered what would happen if we got people to insist on inhabiting these spaces. We wanted to keep the project rooted in the community, but to have an impact at the city and region levels. We wanted to move from illegal demolitions to participatory development. And at the heart of this was the idea of building a platform for community voice. One thing that everyone had said was that they lacked a voice.

So we workshopped this issue, and people came up with quite a literal response. They wanted a radio station. They wanted to be able to speak.

Phase one of Chicoco Radio was to establish the idea of a community radio station, and to gather a cohort of young people from the communities and train them—two years, two and a half years of training. We won't launch until we’re ready, hopefully in about six to nine months. Then, as well as training the people, there was the building of the studios. So technically, we are now ready to go. The transmitter is still in the factory, because only when a total license is granted the frequency gets locked, and it gets released from the factory. But were ready to go on that now.

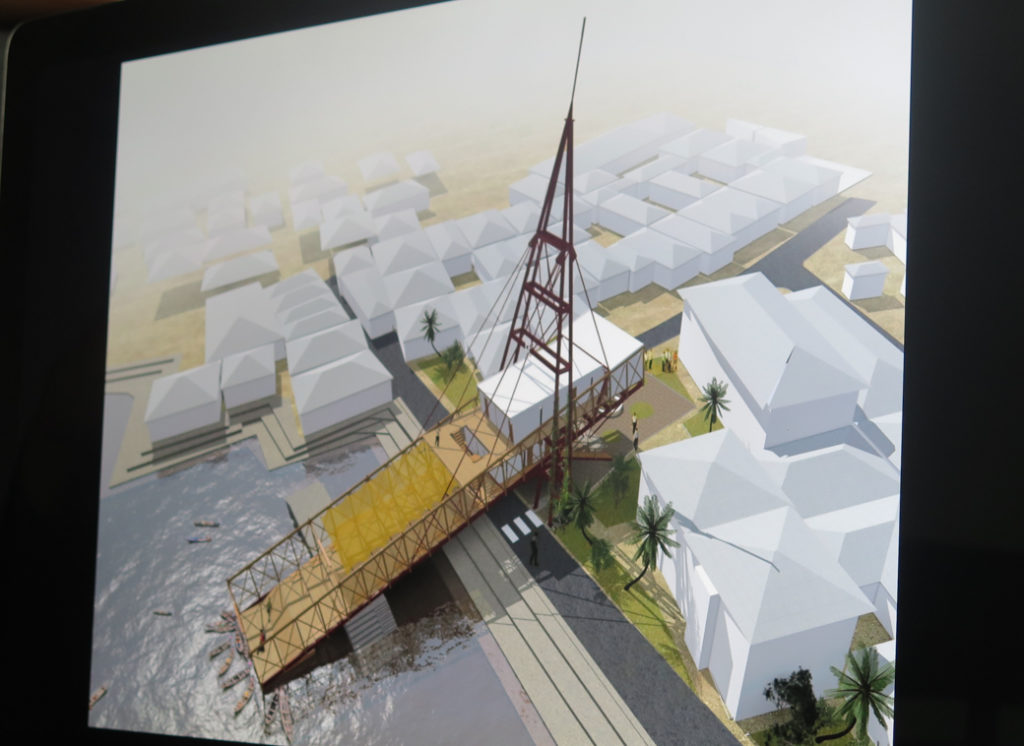

Meanwhile, we will start streaming service. And then we've worked everything out and production is ready, we'll go terrestrial. And soon, we will break ground on this project. At the moment, you'll see where in the Shed [Chicoco’s public performance space]. It's literally a shed. But people said they didn't only want a place where they could speak, but they wanted the building itself to speak, to signal the capacity of communities to contribute creatively to the shaping of their city. They wanted an iconic building.

[Michael decided to stay in Port Harcourt as a filmmaker and activist, documenting abuses by the government and subsequent demonstrations, and raising consciousness through a movement called People Live Here. He and Ana created an initiative called C-Mapping, literally engaging local communities to map their streets and people to give them a sense of ownership. Michael said, “These communities were not part of the city's development plan. They were not on the map. And we wanted to give communities power to literally put themselves on the map.” That effort continues, but it also led to a more expansive idea: Chicoco.]

Michael: The idea was to let people into this space. We wondered what would happen if we got people to insist on inhabiting these spaces. We wanted to keep the project rooted in the community, but to have an impact at the city and region levels. We wanted to move from illegal demolitions to participatory development. And at the heart of this was the idea of building a platform for community voice. One thing that everyone had said was that they lacked a voice.

So we workshopped this issue, and people came up with quite a literal response. They wanted a radio station. They wanted to be able to speak.

Phase one of Chicoco Radio was to establish the idea of a community radio station, and to gather a cohort of young people from the communities and train them—two years, two and a half years of training. We won't launch until we’re ready, hopefully in about six to nine months. Then, as well as training the people, there was the building of the studios. So technically, we are now ready to go. The transmitter is still in the factory, because only when a total license is granted the frequency gets locked, and it gets released from the factory. But were ready to go on that now.

Meanwhile, we will start streaming service. And then we've worked everything out and production is ready, we'll go terrestrial. And soon, we will break ground on this project. At the moment, you'll see where in the Shed [Chicoco’s public performance space]. It's literally a shed. But people said they didn't only want a place where they could speak, but they wanted the building itself to speak, to signal the capacity of communities to contribute creatively to the shaping of their city. They wanted an iconic building.

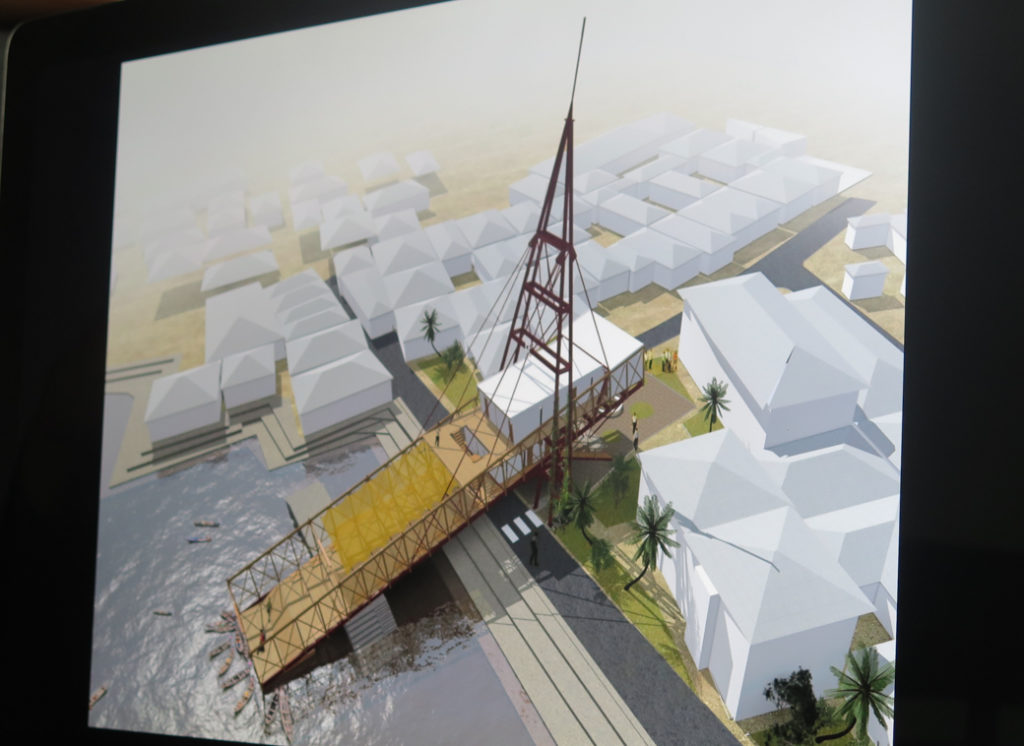

The design of this building, just like all other aspects of this project, has been participatory. It's called Chicoco Space. And before we started thinking about spatial design, we got people together and asked what kinds of values they wanted the building to embody, what kinds of histories they wanted to explore, what kind of futures we wanted to gesture to. And more practically, what kinds of functions did they want to provide.

They voted for things like conference rooms, meeting rooms, cinema, radio, and what we call community spaces, places where people can come together and talk to each other and reach out. So we took that information. We workshopped it with our designers until we got to three design concepts. And then we had a favorite, which was called the Bridge to Transformation. We thought, why don't we literally suspend the building from the mast? And doing that also created space underneath it. Because one of the challenges was to deliver a civic-scale building in a very dense settlement. So by tilting it, floating one edge in the water, and floating the other in the air, we lift the radio studios above an open public space.

[Afropop participated in a “Session at the Shed” where we spoke to members of the Chicoco family about music and social justice in other parts of Africa, and about the art of radio production. For our program, we were especially interested in speaking with young musicians in the community, like St Mercy and Andre Derri.]

[caption id="attachment_36332" align="aligncenter" width="599"]

The design of this building, just like all other aspects of this project, has been participatory. It's called Chicoco Space. And before we started thinking about spatial design, we got people together and asked what kinds of values they wanted the building to embody, what kinds of histories they wanted to explore, what kind of futures we wanted to gesture to. And more practically, what kinds of functions did they want to provide.

They voted for things like conference rooms, meeting rooms, cinema, radio, and what we call community spaces, places where people can come together and talk to each other and reach out. So we took that information. We workshopped it with our designers until we got to three design concepts. And then we had a favorite, which was called the Bridge to Transformation. We thought, why don't we literally suspend the building from the mast? And doing that also created space underneath it. Because one of the challenges was to deliver a civic-scale building in a very dense settlement. So by tilting it, floating one edge in the water, and floating the other in the air, we lift the radio studios above an open public space.

[Afropop participated in a “Session at the Shed” where we spoke to members of the Chicoco family about music and social justice in other parts of Africa, and about the art of radio production. For our program, we were especially interested in speaking with young musicians in the community, like St Mercy and Andre Derri.]

[caption id="attachment_36332" align="aligncenter" width="599"] King DRE (his son Ryan) and St Mercy[/caption]

St Mercy: I'm a Port Harcourt girl, born and raised here. I’ve been pretty interested in music since I was 10. Out here, even though we don't have money, music gives us comfort. You understand? It's where we just relax and feel like it go bettah. So I've been in the music for a while, but still underground, because nobody knows my name. We just do what we love for the sake of love.

I didn't really enjoy African music. It's not that real. It’s just touching the top. They don't go deep. They're not in touch with my present generation. You understand? Even Fela, the tunes are strange to listen to. But I can just go online and read the lyrics, and understand. What did this guy say in the song? Just checking on Google, and read what the lyrics said, "Wow. Nice.” Because if you just listen to the tune, you won't really understand. It doesn't sound like what we know now. But it's what we're facing now. It's quite present. He prophesied. So now we're just facing everything he talked about.

There's a kind of oppression here. They want to oppress you—everyone here. If it's not the landlord, it will be the cultists [gang members], if it's not from the cultists, it will be from the police. If it's not from the police, oh, it's from the government. The lifestyle is just depressing. You can't live your life freely. It's like now you just have to work for the cash. If you don't have the cash, you just have to suffer. You can't be comfortable. You can just be sitting in your house one day, and some police will just come in slap you and take you.

I will give you an example. I was at work yesterday at the salon and these anticultism guys came around. We were just inside. Someone just stepped out after cutting the hair, and they met him on the way and told him to undress. Start tearing his shirt, beating him. For what? For no reason. They do it often. They just wait for young people. Once they see you're looking cool, they say, "Let me f___ this guy up." They just beat you. They behave like ex-convicts, people who been imprisoned for years. They're not happy. They don't want to see you happy. There's just like this wickedness. Show you irab. In Nigeria we call it irab when somebody oppresses you and makes you feel bad. “I will show you irab, and spoil your thing for you.”

They are in uniform. They wear boots. They dress like people who are going to chase down robbers. But they don't chase down robbers. They just stand on the street and wait for you to come out. You might just be walking with your friend, and they come in slap you. "Where you going to? Where you going to?" They arrived there when some customers are leaving the salon. Because on Saturday, salons close late. Because most customers work from Monday to Friday. Come there on Saturday. So by 12 o'clock, we are still working, in the middle of the night. So after they cut their hair, they're going home in their car, and the same military guys, these police guys, just stop them and brought out their kaboko, a very strong cane, ask them to come down.

RAPPING: I hear voices. Yet all I see is kept silent. Police brutality and politics that cause violence. I hear sirens. Ambulance with dead bodies of the minors. After we vote, they stop to mind is. Wash their hands of our case like Pontius Pilate. Propaganda and lies. Now them use bias. These men they don't see us. Not only do we see them, but they say that we need them. Our money, they sue them. All these things now they make me verse quick. They make us promises, and when they when they forget quick. Make the young ones think of death quick. The system is sick.

[caption id="attachment_36301" align="aligncenter" width="563"]

King DRE (his son Ryan) and St Mercy[/caption]

St Mercy: I'm a Port Harcourt girl, born and raised here. I’ve been pretty interested in music since I was 10. Out here, even though we don't have money, music gives us comfort. You understand? It's where we just relax and feel like it go bettah. So I've been in the music for a while, but still underground, because nobody knows my name. We just do what we love for the sake of love.

I didn't really enjoy African music. It's not that real. It’s just touching the top. They don't go deep. They're not in touch with my present generation. You understand? Even Fela, the tunes are strange to listen to. But I can just go online and read the lyrics, and understand. What did this guy say in the song? Just checking on Google, and read what the lyrics said, "Wow. Nice.” Because if you just listen to the tune, you won't really understand. It doesn't sound like what we know now. But it's what we're facing now. It's quite present. He prophesied. So now we're just facing everything he talked about.

There's a kind of oppression here. They want to oppress you—everyone here. If it's not the landlord, it will be the cultists [gang members], if it's not from the cultists, it will be from the police. If it's not from the police, oh, it's from the government. The lifestyle is just depressing. You can't live your life freely. It's like now you just have to work for the cash. If you don't have the cash, you just have to suffer. You can't be comfortable. You can just be sitting in your house one day, and some police will just come in slap you and take you.

I will give you an example. I was at work yesterday at the salon and these anticultism guys came around. We were just inside. Someone just stepped out after cutting the hair, and they met him on the way and told him to undress. Start tearing his shirt, beating him. For what? For no reason. They do it often. They just wait for young people. Once they see you're looking cool, they say, "Let me f___ this guy up." They just beat you. They behave like ex-convicts, people who been imprisoned for years. They're not happy. They don't want to see you happy. There's just like this wickedness. Show you irab. In Nigeria we call it irab when somebody oppresses you and makes you feel bad. “I will show you irab, and spoil your thing for you.”

They are in uniform. They wear boots. They dress like people who are going to chase down robbers. But they don't chase down robbers. They just stand on the street and wait for you to come out. You might just be walking with your friend, and they come in slap you. "Where you going to? Where you going to?" They arrived there when some customers are leaving the salon. Because on Saturday, salons close late. Because most customers work from Monday to Friday. Come there on Saturday. So by 12 o'clock, we are still working, in the middle of the night. So after they cut their hair, they're going home in their car, and the same military guys, these police guys, just stop them and brought out their kaboko, a very strong cane, ask them to come down.

RAPPING: I hear voices. Yet all I see is kept silent. Police brutality and politics that cause violence. I hear sirens. Ambulance with dead bodies of the minors. After we vote, they stop to mind is. Wash their hands of our case like Pontius Pilate. Propaganda and lies. Now them use bias. These men they don't see us. Not only do we see them, but they say that we need them. Our money, they sue them. All these things now they make me verse quick. They make us promises, and when they when they forget quick. Make the young ones think of death quick. The system is sick.

[caption id="attachment_36301" align="aligncenter" width="563"] Banning Eyre and Andre Derri A.K.A. King DRE[/caption]

Andre Derri: O.K., my name is Andre Derri, best known as King DRE. That's my stage name of our rapper and a mapper as well. And I'm training at Chicoco Radio. That's just me. When I was coming up as a boy, I was dancing in church, and my cousin was rapping. So he was the one who actually introduced me to rapping. I fell in love with rap and the culture of hip-hop. It's a way of life, an inherited culture from the West. So I fell in love. We would go to represent our school. People loved me that because I was small and I was rapping. I hadn't started writing my own songs. We were miming songs from celebrities like Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and the rest of them. It was really fun. Because when I rap it would be hearing me, and I thought, "Whoa, this is good. I love the feeling I'm getting from the fans in the audience."

In our churches here we do these children’s days. They would just bring us up together. We would dance a choreographed dance, maybe to a Diana Ross song. Most of the time, "He Lives in Me" and things like that. But I had to start changing things in church. When I started rapping, I decided that I wasn't going to dance anymore. I want to rap. It was fun, because it was more like I was doing something new. I was bringing something new to the church. And everybody liked that. They would say, "Next year, we want you to rap again." So I was loving it. It was really fun.

But somehow, it was a bit difficult, because, you know, the church has its own culture. It's a religion. You have to mind the kind of words you use when rapping. I kind of love using any kinds of words I want to use, especially the F word. That's what I was actually taught, right from the beginning of doing this whole rap, hip-hop thing. But I hadn't understood the market in Nigeria. I really did not care then. All I wanted to do was rap and use any kind of words I wanted to use. Because my fans loved it when I represented my school in the school shows and all that. They loved it. So I was just doing my thing.

I'm a grown man now. I know what I want now. I do go to church. And I have some good songs as well that I can sing in church, and once I can still sing in clubs, and my street songs.

My first song was about a girl. I wasn't actually expressing myself in that song. It was a friend who wrote the song. He wanted a rap verse, so I had to actually think of something to give to him. Actually I wasn't experiencing any heartbreak then. He was talking about heartbreak. He was older than me, but he loved the way I rapped. So he said I should jump on the track, and I was somehow confused, because I don't have a girlfriend that broke my heart, why would I be saying something about breakup when I don't even know? I had to listen to songs, different kinds of hip-hop songs, just to be able to think and make up something. It was a lie. My first song was a lie.

Banning Eyre and Andre Derri A.K.A. King DRE[/caption]

Andre Derri: O.K., my name is Andre Derri, best known as King DRE. That's my stage name of our rapper and a mapper as well. And I'm training at Chicoco Radio. That's just me. When I was coming up as a boy, I was dancing in church, and my cousin was rapping. So he was the one who actually introduced me to rapping. I fell in love with rap and the culture of hip-hop. It's a way of life, an inherited culture from the West. So I fell in love. We would go to represent our school. People loved me that because I was small and I was rapping. I hadn't started writing my own songs. We were miming songs from celebrities like Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and the rest of them. It was really fun. Because when I rap it would be hearing me, and I thought, "Whoa, this is good. I love the feeling I'm getting from the fans in the audience."

In our churches here we do these children’s days. They would just bring us up together. We would dance a choreographed dance, maybe to a Diana Ross song. Most of the time, "He Lives in Me" and things like that. But I had to start changing things in church. When I started rapping, I decided that I wasn't going to dance anymore. I want to rap. It was fun, because it was more like I was doing something new. I was bringing something new to the church. And everybody liked that. They would say, "Next year, we want you to rap again." So I was loving it. It was really fun.