Before dashing from my hotel to continue the endless explorations available in the great city of Istanbul, I left time each day for my morning ritual with the older woman who cleaned my room. This short, broad-shouldered lady was a beast when it came to getting in morning hugs and kisses. As if I was still 9 years old and had grown up in her living room, she would pull me close by my cheek to kiss and bless my head before releasing me to the day. The love of one strong-armed Turkish auntie combined with shots of sweet Turkish coffee had me flying over a city that had lived many lives.

Before dashing from my hotel to continue the endless explorations available in the great city of Istanbul, I left time each day for my morning ritual with the older woman who cleaned my room. This short, broad-shouldered lady was a beast when it came to getting in morning hugs and kisses. As if I was still 9 years old and had grown up in her living room, she would pull me close by my cheek to kiss and bless my head before releasing me to the day. The love of one strong-armed Turkish auntie combined with shots of sweet Turkish coffee had me flying over a city that had lived many lives.

From the beginning of civilization, this ancient city has been the cultural crossroads with the historic Silk Road and grand finale of the Grand Bazaar. As a destination that people trek to from far and wide, bringing their finest, Istanbul is excellently set up to be a culture of connoisseurs. In addition to silk, spices and rubies, traveling nomads were ambassadors of their homelands, moving in their own native rhythms. Turkish folk music reflects the influence from visiting ethnicities, including instrumentation from Algeria, Egypt, Bedouin and Berber tribes, and more. From the private drawing rooms of the Ottoman Empire to blue smoke-filled jazz clubs of the ’70s, the Turkish ear has been trained to be the sultan of sound selection.

A topic often left out of the common tour guide is the story of the pillars of civilization, the Afro-Turks. The Ottoman Empire, stretching over centuries, made its rise on the back of slavery. By the early 1600s, a fifth of the population in Istanbul, then called Constantinople, was slaves. The empire had a complicated system of enslavement, including tiered classes within the enslaved populations with restrictions on certain posts. In the ranking between household slaves to empire officials, between Caucasian, European and African, you can probably guess who was served the short end of the stick. On top of race, religion also determined rank, pardoning Muslims, Jews or Christians and creating a demand for slaves from the African Great Lakes region, Central Africa as well as Zanzibar, Niger, Kenya and Sudan. One area reserved only for Africans were the eunuch guards of the concubines of the Ottoman sultan. Young boys captured by clergymen in their home villages were brutally mutilated, in a process that had only a 10 percent survival rate, before being sold as eunuchs. Another area dominated by Africans was soldier-slaves. It has been written that the Ottoman army sent to the Balkans in the Austro-Turkish War of 1716-18 over 24,000 men from Africa. Although many attempts to ban slavery were made, the repulsive repression continued into the early 1900s.

In contemporary Istanbul, there are two veins of African bloodlines. There are the migrants from Somalia, Dijoubti, Nigeria, Cameroon, Senegal and North Africa who have traveled to Istanbul through political partnerships promoting employment opportunities. Often in hope of crossing a gateway that will lead to Western Europe, this increasing demographic is met in the street with looks of uncertainty and harsh stereotypes.

The other vein of African blood trickles down from the descendants of African slaves: Afro-Turks. Mustafa Olpak is credited for first recognizing the group by founding the African Culture and Solidarity Society. Many gifted artists have come from this lineage, including Esmeray Diriker. Born on the European side of the Bosphorus Sea in 1949, her ancestry reaches to Morocco. The public fell in love with her in 1977 with her song ”Gel Tezkere Gel (Discharge Letter to Come),” giving voice to the homesickness felt by Turkish soldiers during the mandatory 18-month military service. She continued to have a strong voice and speak on the frustration and prejudice that she endured by having darker skin.

My favorite track, “13, 5,” reveals the story of an Arab girl looking from a window, capturing the feeling of an outsider on the inside. Kornelia Binicewicz helped draw global attention in an excellent piece she wrote for the Abu Dhabi-based The National on Esmeray, describing how the “marching drums break the atmosphere and the low, deep and proud voice…takes us into a different level of understanding about what it means to be a black Turkish girl. Arabic flutes in the refrain leave us with no doubt where this Turkish girl is from.”

Lifting the skirt of the surface feels forbidden in streets where women’s eyes peer from behind burkas. However, my curiosity was whetted and I wanted to go deeper. Sharing dried apricots, sweet tea and salty smiles that stuck to your skin hours later, I crossed the Bosphorus Sea. Rocking gently through the channel that splits the city into pieces, the soft humming of the sun as it kissed the water’s skin began the introductory bars, soon met with the rhythm and chant of hustlers in the street, calling out "books and bread for one lira, one lira…." By the time the luminous calls to prayer dropped in, I was deep in the fold of jazz. Raw taksims, or instrumental improvisations, living through the street sounds that breathed in layers. Echoes of repetition gave the meter as a lover, as a vehicle, rather than as a ball and chain. The city loves jazz, the recognized language to describe not only freedom, but the search for freedom.

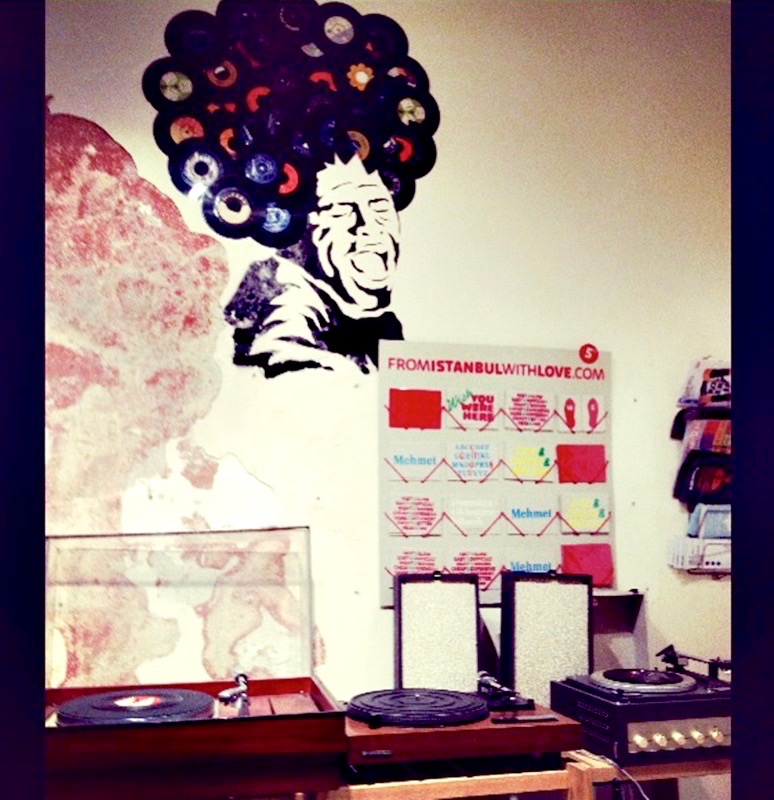

I meandered in and out of windless tunnels of booksellers, past the groups of men linked arm in arm with high-kicking heels in traditional Black Sea dances, and up the steep streets that would lead me to my own mecca. Following the sound advice of friends who love vinyl, I had several destinations to satisfy my interests. Each record-shop owner would take me in for a few hours, lift my eyes to bins of Turkish music and the influence of global sounds. In these shops, I spent hours and decades in headphones, dropping needles into dusty grooves.

My favorite of all the stops was housed in a room no bigger than the guest room at your grandmother’s house, Zoltan's Strange Boutique and Record Store (Caferaga Mahallesi, Sakiz Sokak, 15/D Kadıköy, Istanbul, robotnixx@hotmail.com). The walls, textured from hanging art and features of albums, painted in dark red and black, felt like a club for savvy sound selectors.

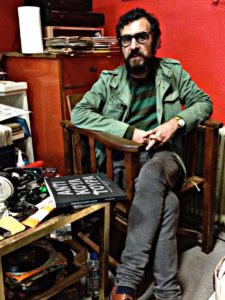

I was lucky to have the owner Emek Can Tὓlὓʂ open his doors to me on his day off. Growing up in Istanbul, he was attracted to the heavier punk sounds that soundtracked liberal left politics and helped to contribute to the collection of album art during the illegal publishing of An Interrupted History of Punk and Underground Resources in Turkey 1978-1999. Sharing sips of warm beer and juice from cans with smoke cloaking our conversations, he revealed his approach to business…and life, and his impeccable taste in music.

Emek Can Tὓlὓʂ, proprietor of Zoltan's Strange Boutique and Record Shop

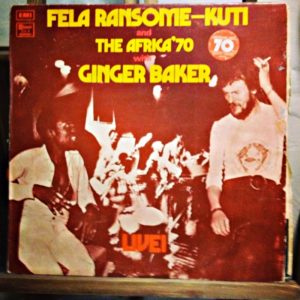

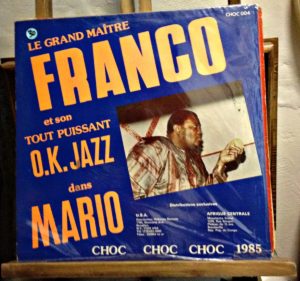

Emek had a way of nodding patiently through my questions, and then pulling from the bins a range of favorites in mint condition and rare finds that took at least a whole side to explain. He unearthed classics in a relatable way. In addition to the Fela Ransome-Kuti and the Africa ’70 with Ginger Baker album I scored that day, I also walked away with a new favorite from the Congo, Franco and TPOK Jazz.

Buying an album featuring a song about a Congolese man living off his rich lady, in a city that castrated young boys from the Congo and posted them as guards to the sultan’s concubines….well, it was more than ironic. There is an immeasurable impact on the imprint of cultural identity from centuries of thinking that relegate people to certain positions of social status based on the color of their skin or the beliefs in their heart. The arts reflect this imprint, such as in the contemporary mythic Arabic tale “Habibi,” a graphic story of the relationship between two escaped child slaves choked by patterns of sexual violence.

Franco Luambo had a long career of fame, playing guitar in a way that earned him the nickname of "Sorcerer of the Guitar." Born in 1938 in what was then the Belgium Congo, it is said that he played several instruments as a boy, particularly the harmonica to entice customers to his mother’s market stand. He founded the OK Jazz band in 1955, which later became Tout Puissant Orchestre Kinshasa, the all-powerful Kinshasa orchestra, or TPOK Jazz. The band went through several formations, swelling to include over 50 members over time. He is considered one of the originators of the modern Congolese sound. Franco became one of the wealthiest men in the country in the mid ‘70s. By the end of the decade, he released two songs that were considered indecent and was sent to prison after a brief trial. After a few months, he was released and a couple of years later was honored as the Grand Master of Zairean music by the Mobutu government. His musical subjects shifted to more patriotic themes and praises to his wealthy fans. In 1985, Franco released his biggest hit ever, Mario, an account of a gigolo who lives off his older lover. Franco died in 1989, resulting in four days of national mourning in Zaire. The stories of survival, of the rise and fall of power…although unique in each place we visit, physically or sonically, hold a similar tone. The taste of richness gives way to greed, and hopefully the salvation of song brings us home.

Several favorites in my stacks take me back to the crowded streets of Istanbul, where moss-covered cobblestones are saturated with the scent of roasted chestnuts, honey and sweet coffee. Each time I go to Istanbul, I leave thinking I may never return … and each time I go back, I could not be happier to be there.

All photos by Tasha Goldberg

For more on this subject, see Afropop's Hip Deep program and related materials: African Slaves in Islamic Lands.