After traveling from London to the Philippines, touching down for two days at home in the Hawaiian islands, then heading to Rio de Janeiro for 10 days of reporting, I was ready for a break. Don’t get me wrong, the fast pace of taking in a diverse range of cultures was more than riveting--but my head was spinning. Sometimes the only way to relieve a heavy head or heart is to simply dance. In search for the kind of sound that would grip my waist and lead, there was no doubt I was Bahia bound.

While reporting at the most participatory conference in the history of the United Nations, the 20th reunion of the U.N. forum on sustainable development, my sensors were aimed at the voice of the people. Rio+20 was successful in ways that can only be truly measured by the outcomes of tomorrow. During the event, I attended an award ceremony acknowledging 25 community leaders who had overcome unjust impacts of climate change despite weak political signals. To honor the intersecting interests, a special performance was delivered by the iconic revolutionary Brazilian singer Gilberto Gil, a man whose own life story followed the unraveling social fabric in Brazil. His tender voice connected the hearts of everyone in attendance, wrapping the story of sustainability into a love song. As he sang, he reached out and grabbed hold of the threads that connect us all and braided them with the sensual softness of love, holding up a flag affirming that revolution is born in the heart.

After all-night celebrations dancing through Lapa, I was ready to leave the city and retreat to Salvador, Bahia. Albert Camus, a man who made being a stranger romantic, wrote that “..the music of the world finds its way more easily into this heart grown less secure.” I decided to let down my veils and open myself to the musical meditations that measure the movement of people.

Sitting along the coast, Bahia is as colorful as it is flavorful. An entry point during slavery, Bahia inherited a wide range of ethnic tribal groups from the western region of Africa, including the Ga-Adandbe, Yoruba, Igbo, Fon, Ashanti, Ewe, Mandinka and other groups native to Guinea, Ghana, Benin, Guinea-Bissau and Nigeria. Bantus are also represented, from Angola, the Congo region and Mozambique. The blending of all groups into an Afro-Brazilian culture is palpable when you taste the acarajé fried dumplings stuffed with spicy shrimp, when you see the wide-hipped women dancing in exaggerated hoop skirts, or when your own hips vibrate from rhythmic nods to home.

At first, my search for vinyl seemed silly in a place pulsing with live drum and dance parades every evening. I had learned of only one store that sold records, so I set off on one of those walks where you allow yourself to get lost, and magically arrived at the lopsided shop on a cobblestone corner. In the front room sat stacks and stacks of books whose covers made me jealous for a universal mind that could take in all words. Then my eyes dropped low… and I saw the lines of bins. In a fairly dramatic move, I dropped to my knees, pulled my hair into a knot and began the dusty finger dance. Each record was new to me. By the time I walked out, I had an armful of history.

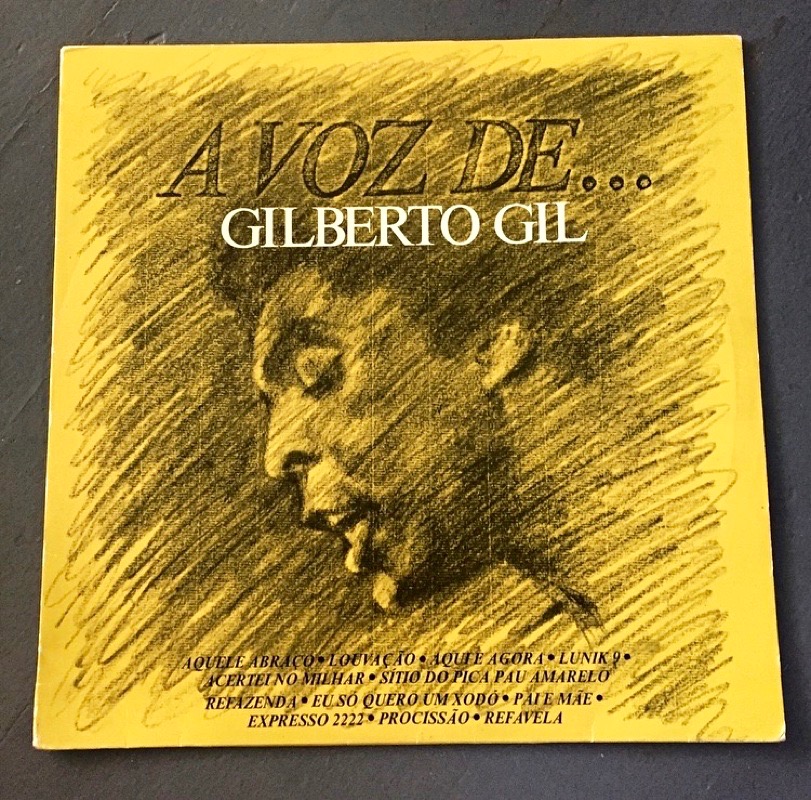

Already warmed to the sounds of Gilberto Gil, I gingerly grabbed A Voz de Gilberto Gil, knowing that there was no way I would be disappointed. Released in 1981 on Fontana, the album is a compilation of poetic pulses that unwind history. The very last song on side B is the one that I fell hard for, “Refavela.” As the title track to the album of the same name released in 1977 on Philips, the album dropped at a crucial time for both Brazil and Gil, shadowing a heavy-handed militaristic ruling government. The oppressive regime was known to censor anyone who did not abide by the new restrictive constitution by jailing, torturing and banishing. Gil was one of the many artists of the time to be arrested and considered a dangerous musical subversive. In 1969, Gil was forced to leave home and deported to London, an experience that perhaps triggered an ancestral memory of the obscenity of slavery. Leveraging his displacement to his advantage, he later acknowledged how those years abroad opened him to new philosophical thoughts and practices. He came home to Bahia in the early ‘70s, fueled by a cool fire that would sustain his strength and secure his eventual appointment as minister of culture, the second black Brazilian to serve in the country's cabinet.

Refavela was recorded a few years after Gilberto returned to Brazil, creating a champion sound to urge black Brazilians to reconnect to their African roots. The album maintains the loving sensual sound that Gil has become known for, acknowledging the beauty in the composite face of Afro-Brazilian identity. Refavela provides a space couched in sensuality, to see, without staring, without averting our eyes to what is in plain sight: the favelas (slums). The musicality and poetry trace jagged lines in the shape of poverty, delivering an appreciation of the beauty of its inhabitants. The song perfects a middle-finger salute to the oppressive history that consistently has devalued the human life of dark-skinned Brazilians. Through a simple act of love and appreciation, Gil protests the injustice by admiring the dark fruits of beauty that is more powerful than the abuse.

Favelas are hard to miss and draw a direct line to time of slavery. Brazil was one of the busiest slave ports in all of the Americas, with some recordings reporting over three million slaves exchanged over three centuries. Take a beat and try to fathom three million people being displaced. By the time slavery was abolished in the late 1880s, at least on paper, the new face of Brazil was forever African. Abolition was followed by a continued period of weak infrastructure, political instability and displaced power. In the region of Bahia, the early favelas formed from families escaping the brutal War of Canudos, the deadliest civil war in Brazilian history. Families seeking refuge from crimes of hate set up tents, which over time became settlements which over time became favelas. These favelas lacked support and infrastructure from the governing bodies and became the fringe reality. Gil honored the families that survived, and perhaps even thrived, in these poor conditions through his lyrics (translated from Portuguese to English):

Refavela…

Paradoxically samba,

Brasileirinho…the accent

But international language

refavela ….

Reveals the shock/ Among the slum-hell and heaven /Baby-blue-rock /On the head /A people-chocolate-and-honey

refavela...Reveals the dream /My soul, my heart /Of my people , my seed /Black Maria, Joe, John /Refavela the refavela/O As is so beautiful, as it is so beautiful,

O refavela…

I was warned by everyone, foreign and local, against visiting the favelas as a woman traveling alone. I admit, I did feel my heart beat in my throat as I took the bus to its last stop on the hill to make my own choice. Through the grit of violence I saw a beautiful light: The time I spent in the favelas was where I experienced the purest love and most genuine opening to a heart of a community. Under the yellow street lights, we gathered to share food, drink, and of course, music. The portal of sound danced us past the present and gave us a flavor of the past. We grew to a new level consciousness for having known one another.

Capoeira in the streets of the favela

Capoeira in the streets of the favela

The truth is, or can, be beautiful. Thank goodness for the hearts of revolutionaries who have the courage to make musical meditations on love, valuing these shredded stories. Once we have placed our value, our interest, our hearts on a subject served to us through soundways, then we will naturally care for it. We are, after all, still human. And the voices in vinyl remind us of that, ever so tenderly.

All photos by Tasha Goldberg