It did not take long for me to feel at home in the city of Dakar. As soon as I landed--a day the city also welcomed the visiting King of Morocco--sounds from the streets were drumming high vibrations. I literally landed in the middle of a proper West African parade celebration! Linked arm and arm with my new Senegalese sisters, who lovingly called me Mama Tadou, I had dates for lunch with the mothers, aunties and markets of Dakar before even collecting my luggage. My new extended family was an automatic network, a team ready to help me feel at home, welcomed and of course find some good wax.

Walking along the seaside with bright boats and fishermen, the pulse of Senegal’s soundtrack is easy to feel. Men in long pale tunics sway in melodic calls to prayer while women juggle body parts under wax prints with rhythm that very well may be the original inspiration for a drum beat. The colors of the fabrics gather and bunch into symbols of sound. I had that familiar feeling of falling in love, and leaned into another sonic adventure.

I drank in the crossroads of cultural identity, downing a few strong French coffees while sipping the sweet bissap juice of hibiscus flowers. Considering that most people who live in Dakar are Senegalese, with less than 10 percent of the population from Europe or Lebanon or elsewhere, I practiced enunciating Wolof more than French. Tastes and timbres gave me insight, as food and sounds often do, to the melting pot of culture in Dakar. Part of the beauty of Senegalese tradition is the layers that overlap cadence, voice and drum; mixed with influences from abroad, be it Malian or Cuban, the final product is a fresh interpretation.

After cruising spiraling miles of stalls in open-air markets, running my fingers over kalimbas and taut drum skins, I found a lead on where to buy records in the slim shadows. Led by the hand from one person to the next, I followed the collection of a composite set of clues transcribed to a napkin map. There has been a heavy traffic of interest in West African vinyl that resurged sometime in the '90s, leaving many of the spots that would be easy to find dry. I crossed the invisible line of where tourists should not find themselves, passing stretches of gravel and broken glass. I turned down each corner designated in my ink coordinates. Just as I was about to give up and walk back towards a main street to find a taxi to take me home, I passed by a sort of stodgy-dodgy English guy with a stack of LPs under his arm. His darting eyes pointed me to a corrugated tin-roof bodega.

I found my destination for digging in Dakar! Under the tin roof shielding the sun’s harsh rays from wax artifacts, I found Mr. Dread Amala, radio show personality, producer and full time hustler. His small shop was brimming with warped records, haphazardly stacked in piles that would make most collectors feel like nails screeching down a chalkboard. At first, I must have appeared to him like a big ol’ American dollar sign. Soon enough the prices went from about $50 a pop to $50 for the lot, with a little persuasion and maybe one or two small kisses on the cheek.

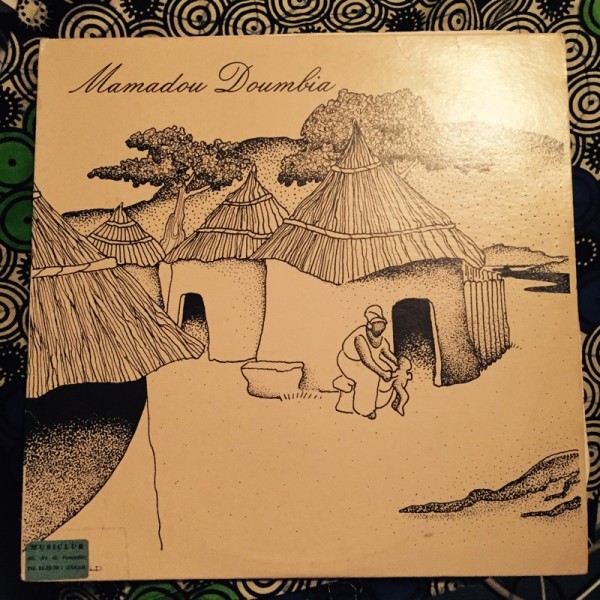

That afternoon satisfied me in ways that I would not fully realize right away, adding several new favorites to my heavy rotation bins. My eye caught one record that I knew I wanted before I recognized the name. The cover had black and white dots softly outlining a village moment where there was palpable love, care and values. Interestingly enough, Mark Greenfield, the artist, had never actually been to Africa at the time he created this scene. It wasn’t until just a few months ago, when I emailed him to learn more about the album, that he had even seen the cover.

The record is music from Abidjan, Ivory Coast: Mamadou Doumbia et Son Ensemble l’Orchestre Conseil de l’Entente. Pressed in 1980 originally in Benin, recorded in the U.S., this LP is the second in a series of five on Eboni Records. Mamadou Doumbia had founded the original band Trio de l’Entente in 1962, which later became the Orchestre de l’Entente (a variation of which is on this record). The sound emerged during a period in West Africa where nightclubs hosted dance bands that played American, Cuban and French music, braided with the traditional polyphonic rhythms and drumming standards from indigenous sounds.

It is in folk music, I suppose, that one finds the simplest most direct use of melody and rhythm. Not until later, when the civilizing process has got well under way, does that simplicity become adulterated. Occasionally such adulteration is harmful, but more often it precedes the creation of art-music, richer, more complex and with possibilities of greater scope and expressiveness. That is the way a culture develops…. (Charles Fox essay)

This record captures a sound that is classic blended highlife composed of West African griots, French orchestral movements, and American-influenced jazz and swing. The ability to layer these influences and create fresh sounds opened the door for the introduction of…well, just about anything. I was floored to read the liner notes and discover that Mamadou Doumbia is not only the composer, but played the lead guitar on a Hawaiian guitar. A basic acoustic Spanish guitar, with the addition of the hard steel bar (applied originally by Joseph Kekuku), along with an adapter placed over the top fret to raise the strings about a quarter-inch higher, and of course the pick invented by Hawaiians to replace the Spanish finger or fingernails, created a sound that made it all the way to West Africa.

The Hawaiian guitar traveled beyond the musician in this case. But how? The legend of Kekuku goes that at the age of 11 in 1885, he picked up a bolt while walking along a railroad and slid it on the strings of his guitar. In 1904, Kekuku left Hawaii for the mainland and Europe to play his songs. He helped to introduce to the world not only Hawaiian music, but Hawaiian guitar. Once the music was recorded, the influence stretched even further. The Hawaiian guitar sound getting to Africa probably had something to do with Harry Hougassian, born to Armenian parents in Bulgaria. After learning Hawaiian guitar from the second or third generation of teachers, he went to Madagascar in 1952 to record seven albums with a local Decca label called Decaphone. Hougassian became a star and his music left Madagascar and spread across the Indian Ocean to mainland Africa. After he introduced the sound, he paved the way for more greats to break into the sound scene. One of the many was known as "Jhimmy de la Hawaiienne" (Zacherie Elenga) from Congo-Brazzaville who recorded with Opika between 1950 and 1952. His “electric guitar played with a slack key-style open tuning, and played with Bigsy vibrato in an attempt to sound like a steel guitar… (was) an important precursor of African rumba… Jhimmy showed a strong Hawaiian inspiration in his guitar style.” (George Kanahele).

Mamadou Doumbia, from the Ivory Coast, was part of a cultural and economic shift in the 1960s and 1970s. From the riches amassed from chocolate and coffee, the acquired wealth afforded the colony an opportunity to import from elsewhere. Sonically, this meant music from France and the U.S. as well Ghanaian highlife and Congolese rumba. The digestion of these delicacies gave artists in Abidjan a particular style of urban music that eventually took hold across Africa, giving the world the Ivorian accent. Mamadou Doumbia followed a similar trajectory, first singing in French and Spanish in the early years and later composing in Bété or Dioula, the languages commonly spoken in the Ivory Coast. It is impossible to overlook the influence of American funk on African sounds during this time period. West Africa received the signals of funk and jazz from radio and records, as well as touring artists who came to Africa. By 1968, when James Brown, along with his favorite horn master Fred Wesley, had come to give a private concert to then-president Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Africans knew, loved and accepted the funk. Wesley told a reporter after touching down in Abidjan: “We were mobbed at the airport…We'd see women doing our dances, you could tell how much they were influenced by America. James loved the drive of African music….the same beat and chords, but they had that hard drive.” When it came time to record this album, Mamadou Doumbia went straight to the source for the recording sessions, bringing in none other than Mr. Fred Wesley. In the track "Monami-O" we hear how good it feels when it all comes together.

In recognizing the visual fantasy of Africa, created by a guy in Hollywood who had never been to the continent, I ended up discovering an album that demonstrates the braid of cultural identity in a moment in time. Replaying the tracks over and over, I start to hear the dialogue between Hawaiian sensibility, West African tradition and American funk. What a session that would have been to sit in on! Over 30 years later, music that feels good. Thank goodness we have the voices in vinyl to tell us the stories of how we have all come to dance together.

All photos by Tasha Goldberg