I crossed Customs’ hypnotic thick-hipped women laced in fishnets, and entered a tropical sensuality that hummed in neon accents. Sandwiched between offensively hip New Yorkers, a batch of awkward middle-aged Chinese hippies and a six-toed Scandinavian adventurer, I let my headphones slide down. The gorgeous man-child I rented my Havana flat from escorted me to a vintage turquoise Chevy chariot that was almost curvier than me. I blushed as I realized that my fantasies were the cornerstones of a sub-system of commerce. Each and every desire I had could be fulfilled in the black market. Dropping into slow motion, I began to recognize the thin lines. Pondering authenticity, I ran my fingers along the traces of diesel fumes and dilapidated landscapes while winds whipped my hair from my bun….and just like that, the dance began.

Cuba is on the curbside of change...again. After 50 years of iced relations with the world, a shift has arrived. There is now an official U.S. presidential push to establish an irreversible normalization to “increase travel, commerce and information flows … to promote freedom.” Popular media is ready to define freedom, casting broad strokes of generalizations in the canvassing for tourism.

I was curious. I wanted to meet Cuba. Not the prepackaged consumer version; I wanted to hear the stories that described the weight of truth, measured out in beat and rhythm. I wanted to tune into the songs that celebrated the ideals that have surfed through the waves of revolution in this small island nation. I wanted to listen to the voices in vinyl.

The humidity of Havana has a way of opening pores of perception, revealing its symphonic poetry. I felt like a giddy girl as I approached the heart of old Havana’s square where vinyl and book sellers gathered around sweet plumeria trees. Almost skipping down the busy promenade, I hop-scotched over potholes and piles of sun-burnt bricks waiting their turn in the snail-rate renovations. The lemon sun demanded taking breaks in the shadows of bold street art; curb couching with squatting musicians. When I arrived at the square, I was received as if I had been expected, like returning to family. Aunties brushed the hair from my eyes as I fumbled through my Spanish vocabulary, nodding with knowing as they pulled out the back bins for favorite pulls. Uncles brought out the stools from under folding tables, unfolding their glasses to locate the specific volumes to pass along to me.

I felt at home within the exchange of knowledge through wax discs. My momma taught me to find the places in the house where you can dance without making the record skip and my pops passed his precious library of vinyl to me, 10 at a time. Along with the collection I inherited from his best friend, my particular love of vinyl has always been more about the discovery than the search. The moments when time elongates, and the world of art, philosophy, social action, poetry and sexuality come together in vibrations.

Many of the albums I found led me to a place called Matanzas. Located in Cuba’s north, just west of the Bay of Pigs (the site of the failed U.S.-backed invasion of 1961), the region is a hotbed of inspired poetry, art and music. Matanzas translates to mean "massacre," referring to the history of 30 Spanish soldiers. After attempting to enlist the help of local fishermen to cross a river to murder an indigenous community, the weight of the soldier’s own armor pulled them to their death when their boats mysteriously were flipped.

One memorable Matanzas track, ‘Tierra de Hatuey,” comes from Los Munequitos de Matanzas, a band that has held together for over three generations. The song pays respect to revolutionaries Hatuey and Guama, who led a 10-year resistance to the Conquest and were among the first fighters during the Cuban War of Independence of 1895. The lyrics make a metaphor of the landscape of Cuba as the awesome beauty of rebellion. Even though they were eventually captured and murdered, to this day their lives have a stamp of Matanzas pride for survival, courage and above all, dignity.

Matanzas was a capital during Cuban sugar production, a kingpin pawn in a mind-bending fuckery of capitalism that benefited no one involved in the work of production. Centuries of cultivation forced fragments of the African diaspora to settle in Matanzas.

The tree of life knows that, whatever happens, the warm music spinning around it will never stop. However much death may come, however much blood may flow, the music will dance men and women as long as the air breathes them…--Eduardo Galeano.

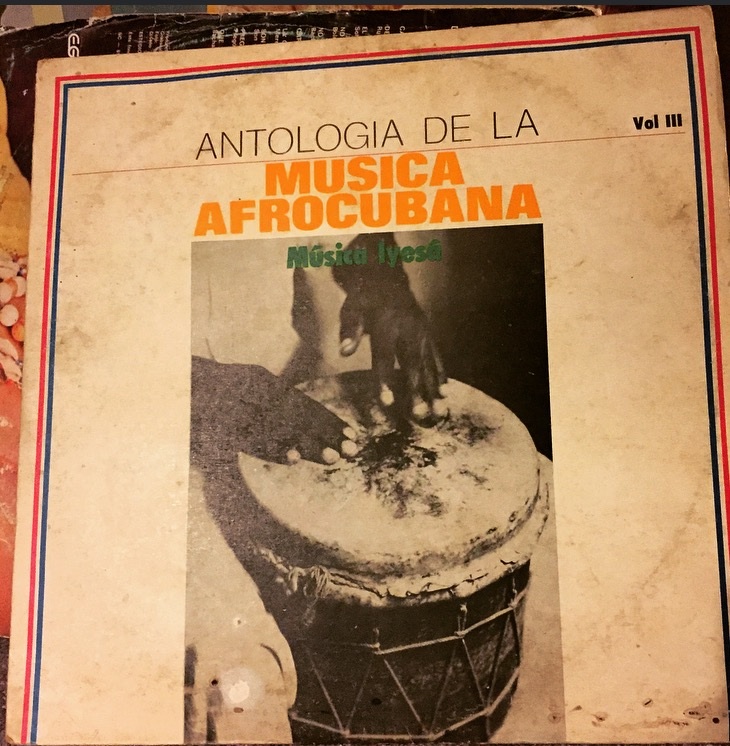

One of my favorite discoveries while crate-digging vinyl in Havana was a series called Afrocuban Anthology Collection. Volume three is recorded by a group of musicians that are direct descendants of a cabildo in Matanzas from 1894. Cabildos or social clubs are institutions created by African descendants living as slaves in Cuba, providing a space to practice religion and experience culture. As a result of these cabildos, songs, dances, stories and instruments that came from the Congo, West Africa, and as far as Mozambique began to meld into a new composite voice that has been identified as Afro-Cuban.

The third album of the series showcases Iyesa, a subgroup of Yoruba culture, sometimes referred to as Yesa, and related to Santeria. Within this complex heritage, people relate to their gods through music; a sonic expression that induces an almost trance-like state. Notions of the nature-based ideologies of Iyesa from Africa seemed to have rooted easily in the similar landscape of Matanzas. Each track embodies a set of values for devotional practice that were reflected in their landscape.

The Matanzas cabildo was particularly dedicated to Ogun and Oshun. Ogun is a powerful warrior orisha who reigns over iron and owns the chain. For a people that were ripped from their homes and enslaved in metal shackles, this high-ranking deity was made musical offerings to appease. The third track is appropriately dedicated to Ogun, considering that his favorite number was three. The track dedicated to Oshun is another favorite, the deity of the rivers and the goddess of love, happiness, wealth, beauty and purification. The promise of her love and sighting of her beauty held the hope that could glue together soul in an indentured life.

The Iyesa sound comes from two to four drums: the caja, the largest; then the segundo or medium sized, followed by the tercero or high-pitched drum; and sometimes a bajo or bass drum. A yesa drum is a type of traditional bembe drum, however instead of a single head played with a curved stick, the yesa is double headed and played horizontally. Only the caja is played with both hand and stick, while the others use strictly sticks. The tracks feature a cowbell, whose sound outlines the entire time cycle, and rattles to emphasize the up-beat.

I left Cuba with far less than when I arrived, and I consider that winning; the best possible outcome of travel. What I did gain were seeds of knowing, etched into two armfuls of vinyl pristinely maintained through the dusty strokes of time. These records became my roadmap to know Cuba, my translator… my discovery of an authentic voice of Cuba, by Cubans.

Watch this space for more adventures in vinyl collecting around the world with the “Voices in Vinyl.”

"Ancient Text Messages: Batá Drums in a Changing World"

YOU WILL ALSO ENJOY: "The Golden Age of Cuban Music"