All photos by Tasha Goldberg

My Merida was destined to be a romance. Seated on a stiff sofa in my hotel library, I looked up to walls lined with perfect white paper-covered books, the value of their contents less on display than an inference of intelligence. Never one to be satiated by broad strokes, I cracked open a vanilla box set to discover vintage texts, yellowed musty pages and all. A small handwritten note fell from the pages onto my lap. I had discovered, or recovered rather, a love letter. A promise and an announcement, "I love you, you are my #1 priority love.” Although not meant for me, my witness of the note delivered a message of love. As I traced the curves in the letters, I knew that the romance in Merida was not just for lovers... it was for those who love. Truth, whether archived as a love note, piece of art, song or graffiti, even when crafted in intimacy, connects us. Deeply, we resonate.

Mexico is a destination I will always say yes to. Inside of the vast country is living history, portraits of the past inside seeds that have yet to bear their fruit. Although the colonial town of Merida never called to me specifically, when given the opportunity to hop a flight south, I was in. In the capital and largest city in the Yucatan, the obvious sights of markets and cathedrals faded and I became enamored by textures on walls, faces, and in harmonies. This old city lived once upon a time as the Mayan cultural center Thó, before the Spanish started counting years. Foreign interests, as in so many tales, swayed focus from domestic demand to glistening riches of export, birthing another slave-built agribusiness empire. According Bernal Diaz del Castillo’s diary from 1517-21 that archived his "discovery and conquest of Mexico," initial interest in Mexico rose out of a sub-successful squad of soldiers and settlers who “possessed no Indians in Cuba and were greedily eager to go to the new land.…” Resistance greeted the Spaniards, strong enough that to this day, more than half of the population remains indigenous.

Arriving on a swell of summer heat, I meandered through humid night markets, passing tails of yarn waving brightly stitched snapshots in the breeze. Pushing back moist curls from my eyes, I added my mug to the framed faces passing each other like admirers of art in a gallery. Although I was the token gringa in the crowd, as sweat rolled down my skin, I began to feel absorbed. Under loudspeakers announcing ballads and bands, I fell into step with local crowds of lovers and families as music handed us the night. In one of my notorious not-lost/not-found adventures, I spotted a cave-like bodega sitting ground level on a pastel-painted residential city block. I walked past at first, before stopping with a smile, realizing that I may have just spotted my lucky record digs. Turning around, I softly came back to the garage-like store. Books, clothes and antique tchotchkes leaned on each other under a thick blanket of dust.

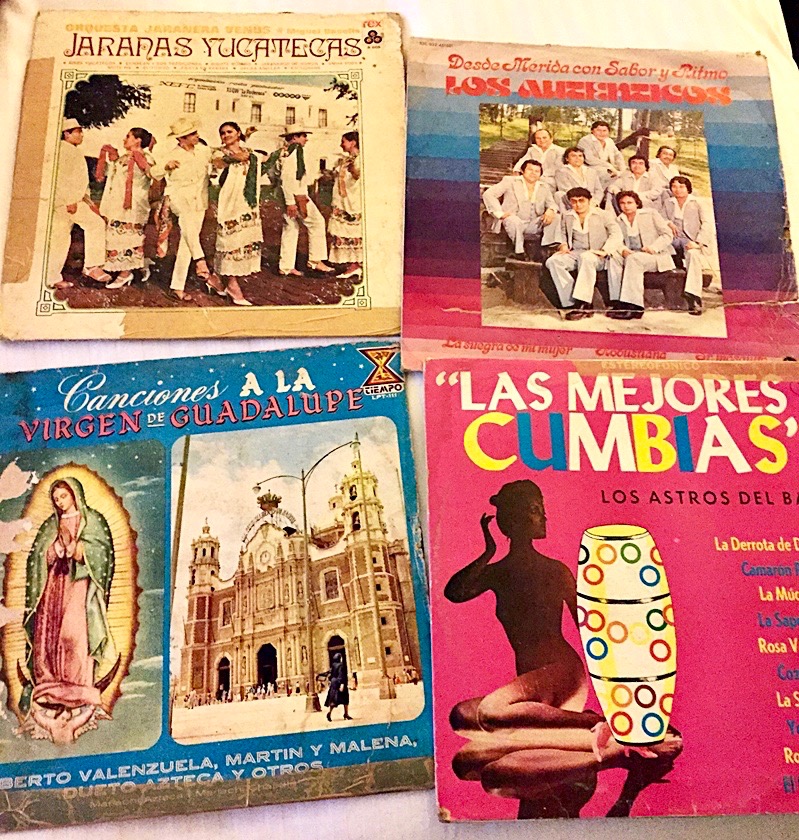

A bold woman in blue, who was clearly in charge of much more than just this little shop, gave me a chin nod. I busted my best pantomime for playing vinyl, dropping the needle in dramatic charades hoping to trigger some clear communication. All of the sudden, her stern stare broke, and she grinned, big. Pulling me by the elbow, we shimmied down a narrow passage of towering opaque glasses to a pile of wax. Excitedly we began pulling from bins, reorganizing and taking stock. After politely denying her generous offer to recover all of the American hits and bring them back to the land that had forgotten them, we finally got to the sweet spot. Auntie Azul lifted a light on the records that were specific to Merida and the Yucatan, Los Authenticos, Jaranas Yucatecas and Canciones a la Virgen de Guadelupe. And in the very back of tunnel of the underground bodega, I found Las Mejores Cumbias.

Mural portraying the sale of Yucatan Indian slaves.

Cumbia is a big reference to a diverse range of music that continues to evolve over time. Musicologists debate over cumbia’s specific origin, some claiming it existed in the indigenous region of Pocabuy (Colombia pre-contact), others relating it to Bantu cumbé, which refers to a rhythm from the island of Bioko in Guinea, West Africa. Perhaps cumbia was born in the union of the musicality of these two different cultures, a rhythmic structure that provides an ode to courtship. Cumbia can be a metaphor for the union or courtship among individuals or cultures, expressed in a simple two count beat. The two-step shuffle, in time with the heartbeat, was a physical enactment of dance done in shackles. Through the portal of music, these bodies discovered love and freedom while inside of a story of slavery. This level of strength of beliefs, resilience of spirit, and undeniable power of people to create beauty inside of a beyond-ugly era is barely recognizable in today’s modern world, where you can literally have a shag, a ride or order a sandwich on demand from your phone.

Music memorializes the values of resilience, strength and poetry so that it is not lost or forgotten, available to replay and recreate centuries later. Music also serves to deliver to today’s generation that reference to slavery is reference to people, humanizing history. Those who were enslaved were lovers, mothers, fathers and children. The original instruments used to create cumbia paint another metaphor for the union of courtship. On African drums, earth and air beat against one another, where the breath of wind comes through the Colombian flutes and shaking echoes from the percussive guacharacas. These sounds came together--it worked--and cumbia was born.

Cumbia traveled from its origin in Colombia, in part because of the popularity of La Sonora Dinamita. With its rotating membership, the band recorded with the Discos Fuentes record label, launching recognition for the band and cumbia in the rest of the world. After the first release in 1958 in Colombia, La Sonora Dinamita: Fiesta en El Caribe, the band followed with the 1960 release, Ritmo.

Cumbia traveled from its origin in Colombia, in part because of the popularity of La Sonora Dinamita. With its rotating membership, the band recorded with the Discos Fuentes record label, launching recognition for the band and cumbia in the rest of the world. After the first release in 1958 in Colombia, La Sonora Dinamita: Fiesta en El Caribe, the band followed with the 1960 release, Ritmo.