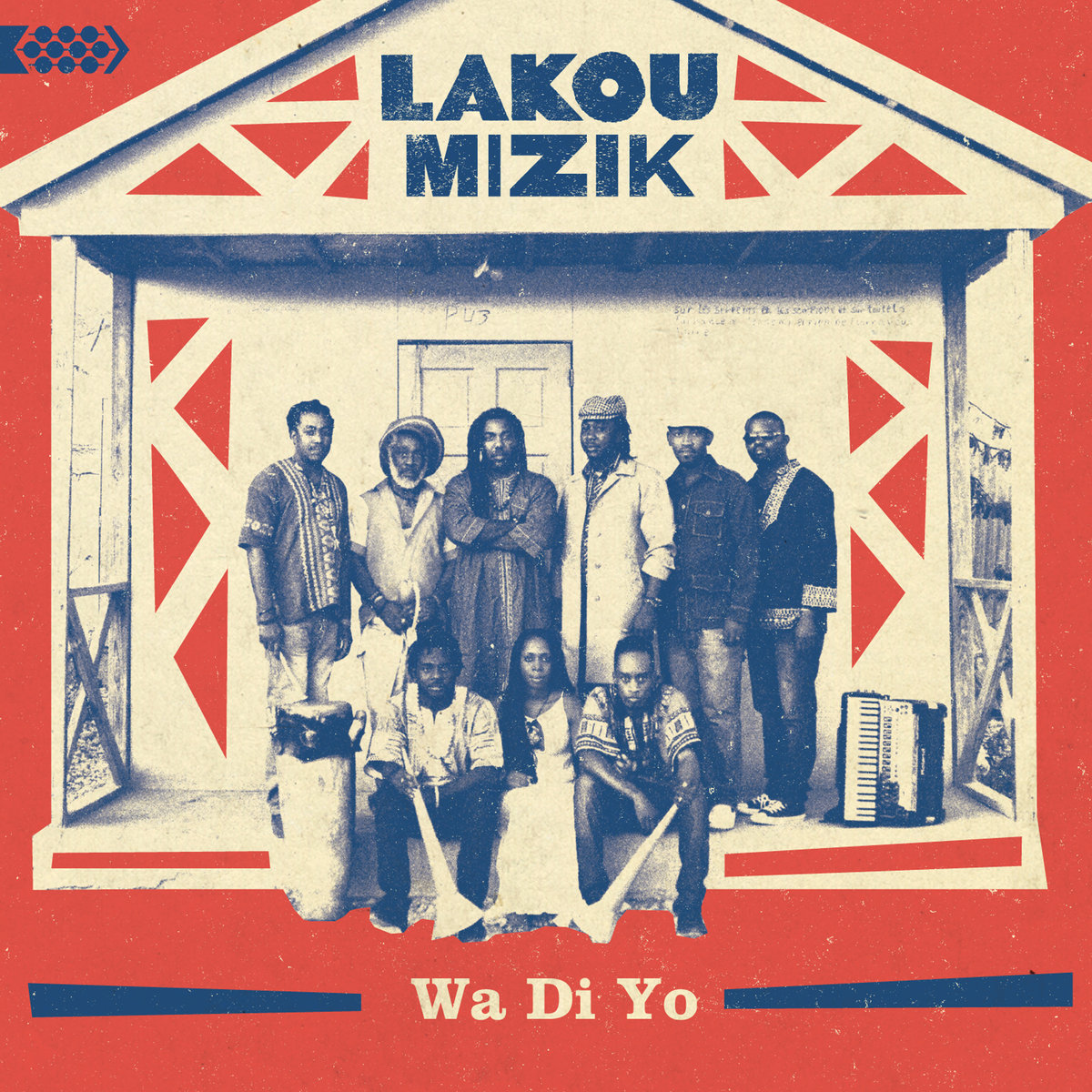

Formed after Haiti's devastating 2010 earthquake, Lakou Mizik is a multigenerational band that's something of a celebration of Haiti itself. Spanning their country's geographic borders, as well as its considerable musical breadth, Wa Di Yo, Lakou Mizik's debut album for the Cumbancha label, feels comfortable and inviting, and a potent reminder of Haiti's unique place, perched at the intersection of African, Caribbean and Francophone culture.

Even if you don't speak Haitian Creole, you can probably guess what mizik means (go ahead, sound it out). Lakou, however, is a bit more ambiguous. According to the band's website: “it can mean the backyard, a gathering place where people come to sing and dance, to debate or share a meal. It also means 'home' or 'where you are from,' which in Haiti is a place filled by the ancestral spirits of all others that were born there. Each branch of the Vodou religion has its own holy place, called a lakou, where practitioners may come together in the shade of a sacred mapou tree.”

Lakou Mizik has that friendly feeling of home. Watching the band members record the handclaps in the studio in the video above, you'd believe that afterwards they'd be heading off to have a meal together. The musicians come from different backgrounds: Steeve Valcourt is the son of Haitian musical legend Boulo Valcourt, who plays in a kompa band; Jonas Attis mixes rara music with reggae and pop; Lamarre Junior and Nadine Remy got their chops in church.

As with any collaboration, there's a risk of everyone being too deferential, everyone holding back on their own strengths to let everyone else shine. But the end results on Wa Di Yo have enough variation to put those fears at ease.

In one of the trailers—the album accompanies a documentary—Boulo Valcourt laments how many more musicians in Haiti are interested in making rap rather than kompa. It's a fair enough concern to worry about one nation's unique musical tradition giving way to the global, American-dollar-bolstered hegemony. But drawing lines around which art made by Haitian artists is sufficiently “Haitian” seems like could risk opening and widening the gulf between culturally bonafide music and what people are actually listening to—call it the Buena Vista Social problem.

Because one of the most enjoyable aspects about listening to Wa Di Yo and indeed much Haitian music, is how it has both a distinct identity, and how it is reminiscent of so many other things at once. The deft accordion playing by Belony Beniste sounds a bit like American Cajun music. The spry interlocking guitars and drums on “Zao Pile Tè” have that West African-by-way-of-Cuba feel, cut in by a toss-and-catch on the horns. There are carnivalesque call-and-response sequences, rara horns, and other staples as firmly Afro-Caribbean as plantain.