Blog December 29, 2015

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song Exhibit at the British Library, London

The British Library is the largest library in the world, according to the number of items in its catalogue, and was initially established as a wing of the British Museum. It occupies a massive public space in the heart of London, midway between the iconic King’s Cross and bustling Euston stations.

There’s something of a bittersweet irony in the fact that the excellent exhibition West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song is housed here, because it showcases artistic aspects of rebellion and anticolonialism as enacted in this culturally rich part of the world, but it is all displayed at an institution that is within the heart of the colonial establishment itself. Yet, that is all the more reason to come and explore what is on offer here, and the curators have obviously given a lot of thought to what they would include and how best to display it. The range of material is staggering, taking in 2000 years of history, spread over what now constitutes 17 different countries, with a total population of 340 million people, where over a thousand different languages are spoken. Kudos are certainly due to Marion Wallace, curator of African collections at the library, and her team for successfully creating a space that does justice to the complex multitude of voices, visions and histories represented here. One could easily spend an entire afternoon exploring the exhibition, so when planning your visit, make sure to allow adequate time.

The entrance to the exhibition is through the library’s gift shop, which already makes it feel as though you are undergoing a back-to-front process of transformation to reach another space, a secret passage to another realm. Once inside the first section, “Building States,” you are confronted with a video loop of Sidike Diabate and his ensemble performing the Manding Sunjata epic; its timeless quality reminds that this region had prominent empires that stretch back at least 2500 years. A bit further along, we’re given a chart that breaks down the wheres and whens of the imperial equation, with the Ife and Benin kingdoms rubbing shoulders with the Wolof, Asante and Oyo empires, and the Sokoto caliphate established at the tail end of the slave trade. There are troubling reminders of the trade itself too, in the form of slave trader Jean Barbot’s 1678 text, Journal of A Voyage to Guinea, but we’re also treated to some incredible artifacts, such as a 120-year-old sheet-brass box from Ghana, which clearly shows the figure of Anansi on it, as well as some protective amulets of the Quadri Sufi order. There are also some massive atumpan drums from Ghana, used to deliver the king’s messages to the people, which anthropologist Robert Sutherland Rattray recorded one Kofi Jatto playing on a field trip in 1921.

Moving into a section labeled “Spirit,” there is diverse representation of the spirit world and matters of faith, including an Ifa divination board from the 1850s, a film clip of a Gelede masquerade, and a noteworthy masquerade book by ethnologist Leo Frobenius, as well as Peggy Harper’s evocative photographs taken in the '60s and '70s. An extensive section on Islam shows its presence in Mali in the 13th century, with a Nigerian Koran of the 18th century also on display, and photographs of koranic boards emphasizing the faith’s regional importance. This is nicely contrasted by a section on Christianity, which is present in the region from the 15th century, but does not take hold until the 19th century, and another surprise comes when we learn that missionaries from Jamaica traveled to the region to proselytize, translating the Bible into local languages. Thus, we have the first Yoruba Bible from 1850, and from 1811, a Bible in Arabic from what is now Senegal. Headphones allow us to hear Josiah Jesse Ransome Kuti—the grandfather of Fela—singing “Jesu Ougbala ni mo F'ori Fun e” (that is, “I Give Myself to Jesus the Saviour”), in a rich baritone, accompanied by a solo piano.

[caption id="attachment_26909" align="aligncenter" width="640"] This image shows a griot (musician and storyteller) with his kora (calabash harp). It is the work of Edmond Fortier, a French photographer who spent nearly 30 years working in West Africa, mainly Senegal, in the early 20th century.[/caption]

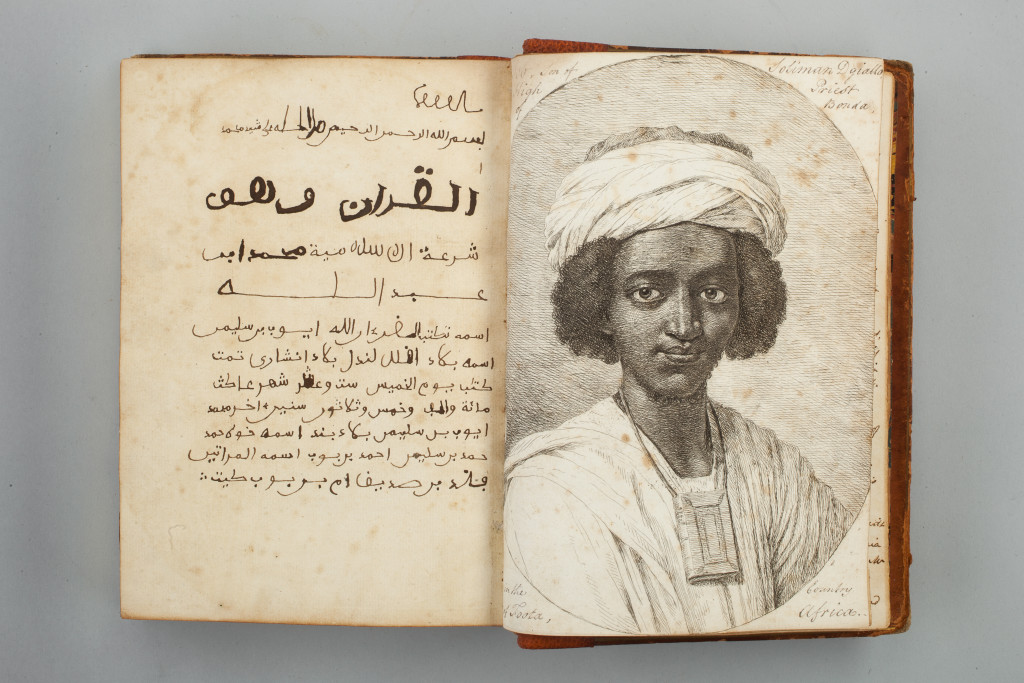

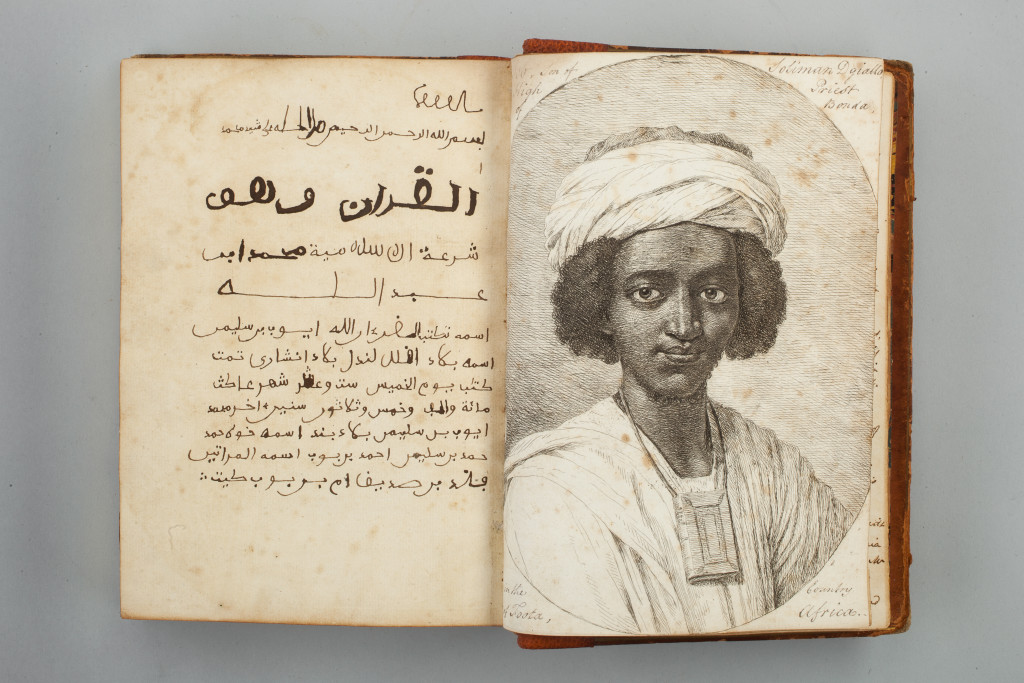

In the “Crossings” section, the strange tale of Catherine Mulgrave Zimmermann also reminds of indelible links between this part of the world and the Caribbean: she was born in 1820 in what is now Angola, enslaved and sent to Jamaica (where she was raised a Christian in the home of the governor of the West Indies), but made her way to Ghana in 1842 as an emancipated woman, where she married Johannes Zimmermann, a missionary from Basel. There is also Ottobah Cugoano, taken from what is now Ghana in 1770 as a 13-year-old slave to toil in Grenada and thence to England, where he obtained his freedom and became active in the abolitionist movement. We learn of Ignatius Sancho, the first black Briton to vote in a British election, and Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (A.K.A. Job ben Solomon), a nobleman from Bundu in modern Senegal, who was shipped to Maryland after being enslaved by Mandingo traders, but who eventually gained his freedom, writing a Koran from memory and later having his memoirs published.

[caption id="attachment_26910" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

This image shows a griot (musician and storyteller) with his kora (calabash harp). It is the work of Edmond Fortier, a French photographer who spent nearly 30 years working in West Africa, mainly Senegal, in the early 20th century.[/caption]

In the “Crossings” section, the strange tale of Catherine Mulgrave Zimmermann also reminds of indelible links between this part of the world and the Caribbean: she was born in 1820 in what is now Angola, enslaved and sent to Jamaica (where she was raised a Christian in the home of the governor of the West Indies), but made her way to Ghana in 1842 as an emancipated woman, where she married Johannes Zimmermann, a missionary from Basel. There is also Ottobah Cugoano, taken from what is now Ghana in 1770 as a 13-year-old slave to toil in Grenada and thence to England, where he obtained his freedom and became active in the abolitionist movement. We learn of Ignatius Sancho, the first black Briton to vote in a British election, and Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (A.K.A. Job ben Solomon), a nobleman from Bundu in modern Senegal, who was shipped to Maryland after being enslaved by Mandingo traders, but who eventually gained his freedom, writing a Koran from memory and later having his memoirs published.

[caption id="attachment_26910" align="aligncenter" width="640"] A qu’ran written by Ayuba Suleiman Diallo featuring his portrait, 1734.[/caption]

Musical items allow us to better appreciate the many African elements that influenced cultures across the Atlantic in this section. The African origin of the banjo, in the form of the akonting lute of the Jola people, serves as a precursor to blues music and bluegrass, and we can hear parallels of Ali Farka Toure and John Lee Hooker’s work on audio clips.

[caption id="attachment_26905" align="aligncenter" width="589"]

A qu’ran written by Ayuba Suleiman Diallo featuring his portrait, 1734.[/caption]

Musical items allow us to better appreciate the many African elements that influenced cultures across the Atlantic in this section. The African origin of the banjo, in the form of the akonting lute of the Jola people, serves as a precursor to blues music and bluegrass, and we can hear parallels of Ali Farka Toure and John Lee Hooker’s work on audio clips.

[caption id="attachment_26905" align="aligncenter" width="589"] JANET TOPP FARGION WITH THE AKONTING INSTRUMENT ON DISPLAY IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY'S WEST AFRICA EXHIBITION. PHOTO BY CLARE KENDALL FOR THE BRITISH LIBRARY.[/caption]

But part of the point of “Crossings” is that the traffic was not only one-way, so we have a Jamaican gumbe drum, which was introduced to Sierra Leone in 1800 by repatriated Jamaican Maroons, becoming firmly entrenched in local musical culture, and Bob Marley’s work is contrasted by that of Alpha Blondy, the Ivorian performer clearly influenced by Marley and his peers. We are introduced to candomble and yemenja as cultural and spiritual practices that survived the Middle Passage, and a section on Carnival culture emphasizes that African-Caribbean cultural elements have gone on to make a huge impact in Britain. Since the overall focus is on West Africa, such elements could easily have been overlooked, and thankfully the inclusion of one of Ray Mahabir’s costumes, along with film and audio clips, reminds of Carnival’s vibrant and dazzling appeal.

[caption id="attachment_26906" align="alignnone" width="640"]

JANET TOPP FARGION WITH THE AKONTING INSTRUMENT ON DISPLAY IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY'S WEST AFRICA EXHIBITION. PHOTO BY CLARE KENDALL FOR THE BRITISH LIBRARY.[/caption]

But part of the point of “Crossings” is that the traffic was not only one-way, so we have a Jamaican gumbe drum, which was introduced to Sierra Leone in 1800 by repatriated Jamaican Maroons, becoming firmly entrenched in local musical culture, and Bob Marley’s work is contrasted by that of Alpha Blondy, the Ivorian performer clearly influenced by Marley and his peers. We are introduced to candomble and yemenja as cultural and spiritual practices that survived the Middle Passage, and a section on Carnival culture emphasizes that African-Caribbean cultural elements have gone on to make a huge impact in Britain. Since the overall focus is on West Africa, such elements could easily have been overlooked, and thankfully the inclusion of one of Ray Mahabir’s costumes, along with film and audio clips, reminds of Carnival’s vibrant and dazzling appeal.

[caption id="attachment_26906" align="alignnone" width="640"] Carnival costume designed by Ray Mahabir of Sunshine International Arts in 2015, based on Bele or Bel Air, a drum dance and song closely linked to Caribbean history, struggle, freedom and celebration. On display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, photographed by Toby Keane[/caption]

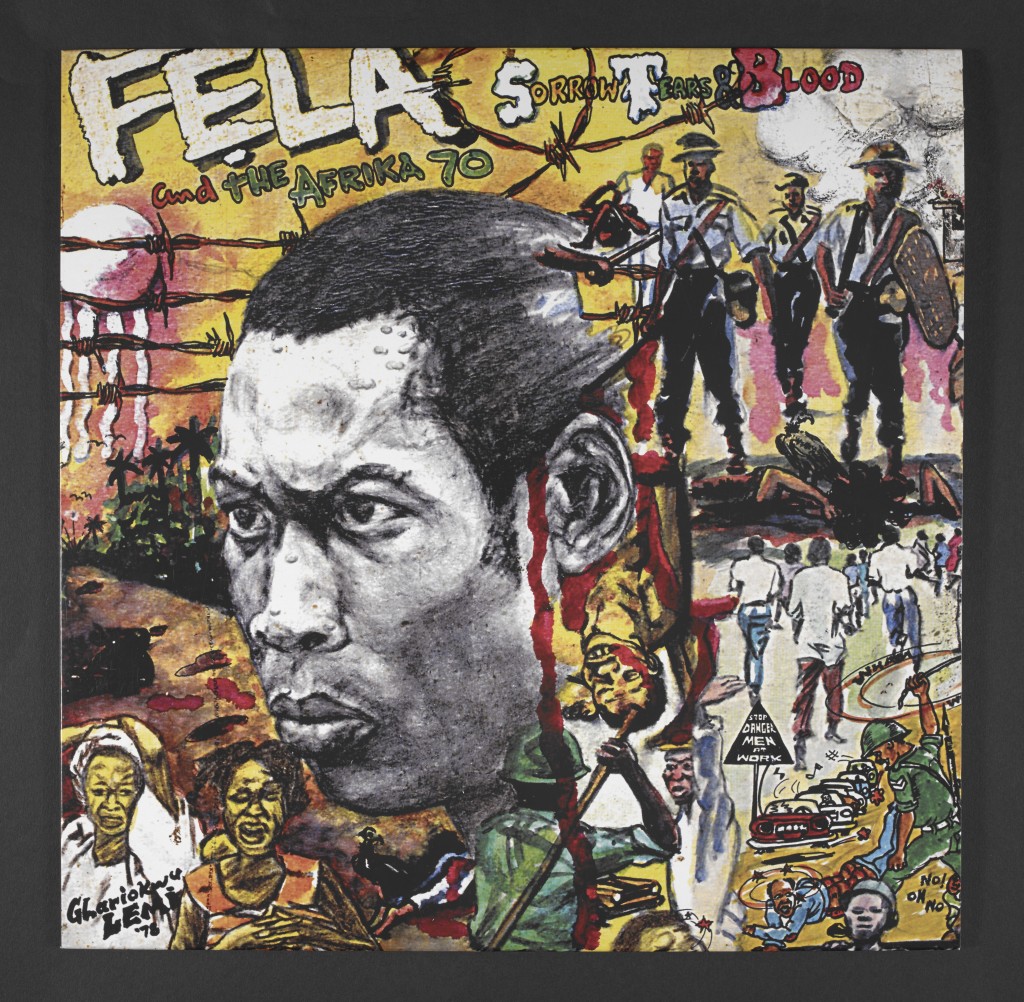

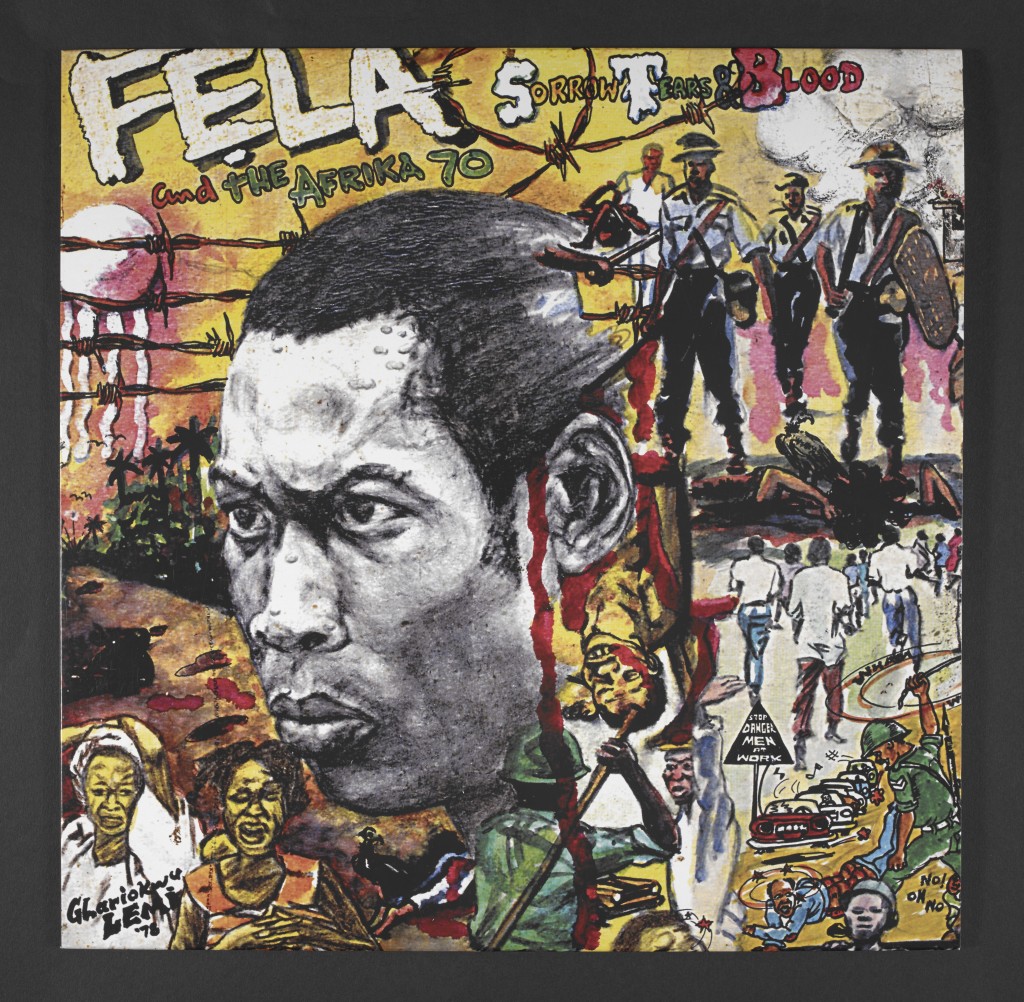

Moving up to the “Speaking Out” section, which looks at dissent in the late colonial era, there are iconic books by figures involved in African freedom struggles, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Sekou Toure and Amilcar Cabral, as well as a prison letter from Ken Saro-Wiwa. There is a stunning 1968 painting by the Nigerian artist, Prince Twins Seven Seven, and some lovely Bembeya Jazz and Syliphone LPs from Guinea. Then we reach the Fela room, a fitting tribute to the maverick Afrobeat pioneer who put his life on the line by perpetually challenging Nigeria’s corrupt political leaders, with eight of his albums prominently displayed, along with a castigating letter he wrote to military dictator Ibrahim Babangida in 1989. Oddly, the film clip displayed is from the recent Finding Fela, a behind-the-scenes look at the Fela musical; there are more pertinent film sources to draw from out there, so I’m not sure where Finding Fela features, but no doubt there was a practical reason behind the choice of footage. There is also a 1954 pamphlet on woman’s rights, written by Fela’s mother, Funmilayo; nearby, clips of Rokia Traore performing “Manian” and Oumou Sangare singing “Dugu Kamalenga” remind that African female artists continue to strive for gender equality in the region.

[caption id="attachment_26911" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Carnival costume designed by Ray Mahabir of Sunshine International Arts in 2015, based on Bele or Bel Air, a drum dance and song closely linked to Caribbean history, struggle, freedom and celebration. On display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, photographed by Toby Keane[/caption]

Moving up to the “Speaking Out” section, which looks at dissent in the late colonial era, there are iconic books by figures involved in African freedom struggles, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Sekou Toure and Amilcar Cabral, as well as a prison letter from Ken Saro-Wiwa. There is a stunning 1968 painting by the Nigerian artist, Prince Twins Seven Seven, and some lovely Bembeya Jazz and Syliphone LPs from Guinea. Then we reach the Fela room, a fitting tribute to the maverick Afrobeat pioneer who put his life on the line by perpetually challenging Nigeria’s corrupt political leaders, with eight of his albums prominently displayed, along with a castigating letter he wrote to military dictator Ibrahim Babangida in 1989. Oddly, the film clip displayed is from the recent Finding Fela, a behind-the-scenes look at the Fela musical; there are more pertinent film sources to draw from out there, so I’m not sure where Finding Fela features, but no doubt there was a practical reason behind the choice of footage. There is also a 1954 pamphlet on woman’s rights, written by Fela’s mother, Funmilayo; nearby, clips of Rokia Traore performing “Manian” and Oumou Sangare singing “Dugu Kamalenga” remind that African female artists continue to strive for gender equality in the region.

[caption id="attachment_26911" align="alignnone" width="640"] Fela Kuti LP cover, Sorrow Tears and Blood[/caption]

The section labeled “Symbol” has some of the most fascinating material of the entire exhibition. We are shown the 2000-year-old Tuareg Tifinagh alphabet, some cowrie-shell letters from 1888, the Vai alphabet from the same period, and the Bamum or Shumom secret script from colonial Cameroon of the 1930s. We learn that the figure of a crocodile can have many meanings, with the example of a two-headed crocodile from Ghana denoting either conflict or collaboration. We are reminded of ways in which drums can talk, and that whistles and horns may also convey messages, and along with examples of millet-pounding songs, we see some hilarious-looking Nigerian and Ghanaian pamphlet texts, such as Life Turns Man Up and Down. A section of beautiful Ghanaian cloths also hold hidden meanings, with an eye-studded design apparently denoting the proverb, “Your eyes can see what your mouth cannot say,” meaning that not every topic is fit for discussion in public. There is cloth depicting the Ghana Guinea Worm Eradication Programme of 1989, and some lovely Aso Oke wedding cloth, as well as another that symbolically states, “Ask questions before you marry.”

[caption id="attachment_26915" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Fela Kuti LP cover, Sorrow Tears and Blood[/caption]

The section labeled “Symbol” has some of the most fascinating material of the entire exhibition. We are shown the 2000-year-old Tuareg Tifinagh alphabet, some cowrie-shell letters from 1888, the Vai alphabet from the same period, and the Bamum or Shumom secret script from colonial Cameroon of the 1930s. We learn that the figure of a crocodile can have many meanings, with the example of a two-headed crocodile from Ghana denoting either conflict or collaboration. We are reminded of ways in which drums can talk, and that whistles and horns may also convey messages, and along with examples of millet-pounding songs, we see some hilarious-looking Nigerian and Ghanaian pamphlet texts, such as Life Turns Man Up and Down. A section of beautiful Ghanaian cloths also hold hidden meanings, with an eye-studded design apparently denoting the proverb, “Your eyes can see what your mouth cannot say,” meaning that not every topic is fit for discussion in public. There is cloth depicting the Ghana Guinea Worm Eradication Programme of 1989, and some lovely Aso Oke wedding cloth, as well as another that symbolically states, “Ask questions before you marry.”

[caption id="attachment_26915" align="alignnone" width="640"] A gold weight in the shape of a two-headed crocodile made in Ghana and used for weighing gold dust, made c 18th – 20th century and on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. The crocodile symbolizes cooperation and interdependence.[/caption]

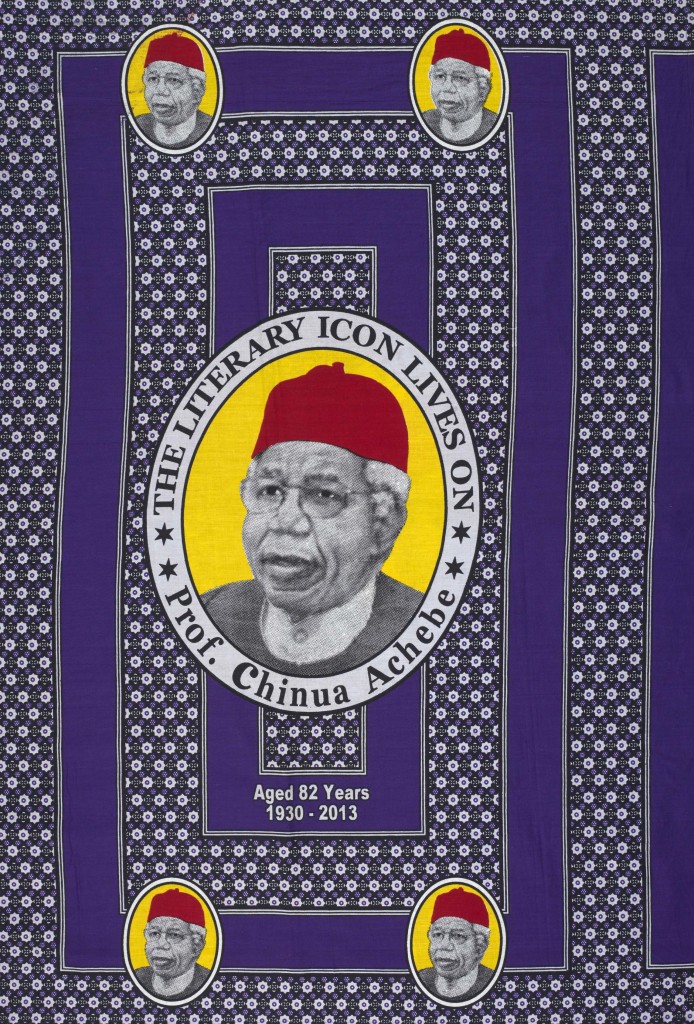

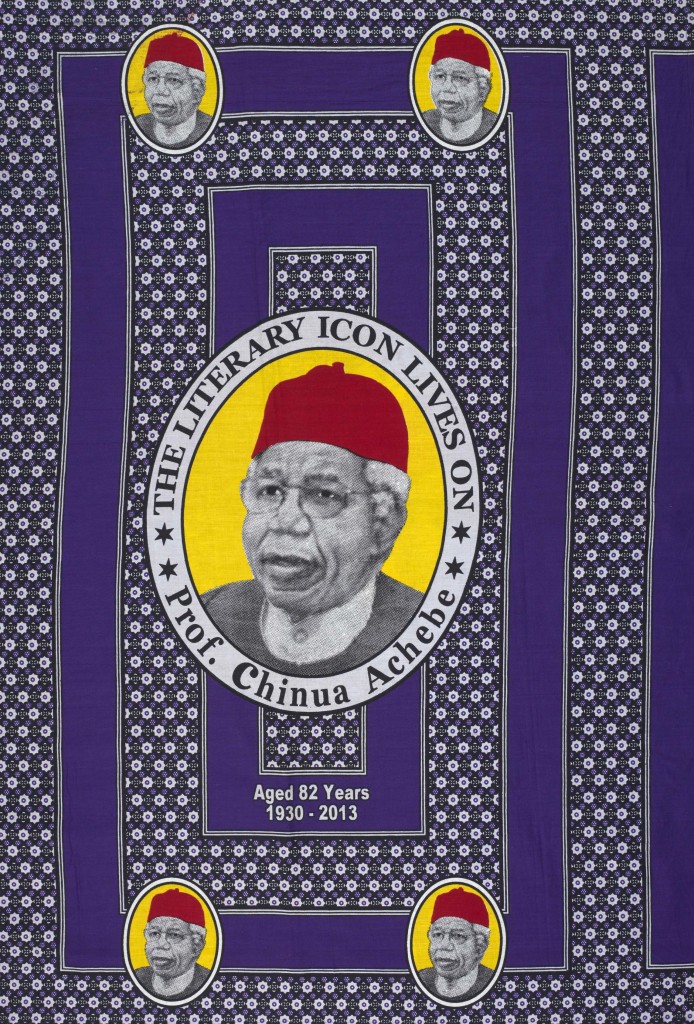

Then we head into the pertinent “Story Now” section, looking at the post-independence period. Here we find Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor collaborating with Marc Chagall in 1973 (following Chagall’s 1971 Dakar exhibition), and the Atoka photo-play magazine, produced in Nigeria in the 1970s. There is a fantastic aluminium relief by Asiru Olatunde from 1968, showing the legend of the Igbo raid on Moremi, and there is footage of Chinua Achebe speaking at the ICA in 1986, as well as his letter to Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey, and a commemorative cloth of Achebe’s literary landmark, Things Fall Apart. Other prominent post-colonial authors included in this section are Ama Ata Aidoo, Ousmane Sembene and Wole Soyinka, while the role of the Mbari Mbayo Club and its magazine, Black Orpheus, in stimulating the Nigerian literature of the pre- and post-independence periods is also featured.

[caption id="attachment_26907" align="alignnone" width="640"]

A gold weight in the shape of a two-headed crocodile made in Ghana and used for weighing gold dust, made c 18th – 20th century and on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. The crocodile symbolizes cooperation and interdependence.[/caption]

Then we head into the pertinent “Story Now” section, looking at the post-independence period. Here we find Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor collaborating with Marc Chagall in 1973 (following Chagall’s 1971 Dakar exhibition), and the Atoka photo-play magazine, produced in Nigeria in the 1970s. There is a fantastic aluminium relief by Asiru Olatunde from 1968, showing the legend of the Igbo raid on Moremi, and there is footage of Chinua Achebe speaking at the ICA in 1986, as well as his letter to Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey, and a commemorative cloth of Achebe’s literary landmark, Things Fall Apart. Other prominent post-colonial authors included in this section are Ama Ata Aidoo, Ousmane Sembene and Wole Soyinka, while the role of the Mbari Mbayo Club and its magazine, Black Orpheus, in stimulating the Nigerian literature of the pre- and post-independence periods is also featured.

[caption id="attachment_26907" align="alignnone" width="640"] Cloth commemorating Chinua Achebe on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. Nigeria, c.2013.[/caption]

Past a circular hut that forms a kind of communal reading space, there’s a final section on the present and future of the region too, with some shocking Nollywood posters for films like My Virginity, My Pride, and clips of contemporary authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Sefi Atta and Lanrewaju Adepoju reading their work.

When you find yourself back in the book shop, the most obvious thing to do is obtain a copy of the companion photo book produced for the exhibition, edited by Gus Casely-Hayford, Janet Topp Fargion and Marion Wallace. The book teases out the themes explored in the exhibition, providing much cultural and historical context behind what is on display. Though always kept accessible for the general reader, the book provides a lot of further food for thought, and I particularly enjoyed Insa Nolte’s chapter on religion; the chapter on the trans-Atlantic crossings of word and music by Fargion, Wallace and Lucy Duran; and Casely-Hayford’s opening chapter on West Africa in precolonial times.

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, succeeds partly because it is so full of surprises. It offers different ways of thinking about the region’s history, evolution and popular culture, yet leaves room for the audience to draw their own conclusions. Exhibitions on Africa are typically somewhat uncommon and ones of such wide scope far less so; related events, such as the Felabration Afrobeat night staged to coincide with the exhibit’s extended opening hours, also makes clear that the viewpoint is not an elitist one. The exhibit, at the British Library, London, until Feb. 16, 2016, is a must-see for anyone who has the opportunity to experience it.

Cloth commemorating Chinua Achebe on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. Nigeria, c.2013.[/caption]

Past a circular hut that forms a kind of communal reading space, there’s a final section on the present and future of the region too, with some shocking Nollywood posters for films like My Virginity, My Pride, and clips of contemporary authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Sefi Atta and Lanrewaju Adepoju reading their work.

When you find yourself back in the book shop, the most obvious thing to do is obtain a copy of the companion photo book produced for the exhibition, edited by Gus Casely-Hayford, Janet Topp Fargion and Marion Wallace. The book teases out the themes explored in the exhibition, providing much cultural and historical context behind what is on display. Though always kept accessible for the general reader, the book provides a lot of further food for thought, and I particularly enjoyed Insa Nolte’s chapter on religion; the chapter on the trans-Atlantic crossings of word and music by Fargion, Wallace and Lucy Duran; and Casely-Hayford’s opening chapter on West Africa in precolonial times.

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, succeeds partly because it is so full of surprises. It offers different ways of thinking about the region’s history, evolution and popular culture, yet leaves room for the audience to draw their own conclusions. Exhibitions on Africa are typically somewhat uncommon and ones of such wide scope far less so; related events, such as the Felabration Afrobeat night staged to coincide with the exhibit’s extended opening hours, also makes clear that the viewpoint is not an elitist one. The exhibit, at the British Library, London, until Feb. 16, 2016, is a must-see for anyone who has the opportunity to experience it.

This image shows a griot (musician and storyteller) with his kora (calabash harp). It is the work of Edmond Fortier, a French photographer who spent nearly 30 years working in West Africa, mainly Senegal, in the early 20th century.[/caption]

In the “Crossings” section, the strange tale of Catherine Mulgrave Zimmermann also reminds of indelible links between this part of the world and the Caribbean: she was born in 1820 in what is now Angola, enslaved and sent to Jamaica (where she was raised a Christian in the home of the governor of the West Indies), but made her way to Ghana in 1842 as an emancipated woman, where she married Johannes Zimmermann, a missionary from Basel. There is also Ottobah Cugoano, taken from what is now Ghana in 1770 as a 13-year-old slave to toil in Grenada and thence to England, where he obtained his freedom and became active in the abolitionist movement. We learn of Ignatius Sancho, the first black Briton to vote in a British election, and Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (A.K.A. Job ben Solomon), a nobleman from Bundu in modern Senegal, who was shipped to Maryland after being enslaved by Mandingo traders, but who eventually gained his freedom, writing a Koran from memory and later having his memoirs published.

[caption id="attachment_26910" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

This image shows a griot (musician and storyteller) with his kora (calabash harp). It is the work of Edmond Fortier, a French photographer who spent nearly 30 years working in West Africa, mainly Senegal, in the early 20th century.[/caption]

In the “Crossings” section, the strange tale of Catherine Mulgrave Zimmermann also reminds of indelible links between this part of the world and the Caribbean: she was born in 1820 in what is now Angola, enslaved and sent to Jamaica (where she was raised a Christian in the home of the governor of the West Indies), but made her way to Ghana in 1842 as an emancipated woman, where she married Johannes Zimmermann, a missionary from Basel. There is also Ottobah Cugoano, taken from what is now Ghana in 1770 as a 13-year-old slave to toil in Grenada and thence to England, where he obtained his freedom and became active in the abolitionist movement. We learn of Ignatius Sancho, the first black Briton to vote in a British election, and Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (A.K.A. Job ben Solomon), a nobleman from Bundu in modern Senegal, who was shipped to Maryland after being enslaved by Mandingo traders, but who eventually gained his freedom, writing a Koran from memory and later having his memoirs published.

[caption id="attachment_26910" align="aligncenter" width="640"] A qu’ran written by Ayuba Suleiman Diallo featuring his portrait, 1734.[/caption]

Musical items allow us to better appreciate the many African elements that influenced cultures across the Atlantic in this section. The African origin of the banjo, in the form of the akonting lute of the Jola people, serves as a precursor to blues music and bluegrass, and we can hear parallels of Ali Farka Toure and John Lee Hooker’s work on audio clips.

[caption id="attachment_26905" align="aligncenter" width="589"]

A qu’ran written by Ayuba Suleiman Diallo featuring his portrait, 1734.[/caption]

Musical items allow us to better appreciate the many African elements that influenced cultures across the Atlantic in this section. The African origin of the banjo, in the form of the akonting lute of the Jola people, serves as a precursor to blues music and bluegrass, and we can hear parallels of Ali Farka Toure and John Lee Hooker’s work on audio clips.

[caption id="attachment_26905" align="aligncenter" width="589"] JANET TOPP FARGION WITH THE AKONTING INSTRUMENT ON DISPLAY IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY'S WEST AFRICA EXHIBITION. PHOTO BY CLARE KENDALL FOR THE BRITISH LIBRARY.[/caption]

But part of the point of “Crossings” is that the traffic was not only one-way, so we have a Jamaican gumbe drum, which was introduced to Sierra Leone in 1800 by repatriated Jamaican Maroons, becoming firmly entrenched in local musical culture, and Bob Marley’s work is contrasted by that of Alpha Blondy, the Ivorian performer clearly influenced by Marley and his peers. We are introduced to candomble and yemenja as cultural and spiritual practices that survived the Middle Passage, and a section on Carnival culture emphasizes that African-Caribbean cultural elements have gone on to make a huge impact in Britain. Since the overall focus is on West Africa, such elements could easily have been overlooked, and thankfully the inclusion of one of Ray Mahabir’s costumes, along with film and audio clips, reminds of Carnival’s vibrant and dazzling appeal.

[caption id="attachment_26906" align="alignnone" width="640"]

JANET TOPP FARGION WITH THE AKONTING INSTRUMENT ON DISPLAY IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY'S WEST AFRICA EXHIBITION. PHOTO BY CLARE KENDALL FOR THE BRITISH LIBRARY.[/caption]

But part of the point of “Crossings” is that the traffic was not only one-way, so we have a Jamaican gumbe drum, which was introduced to Sierra Leone in 1800 by repatriated Jamaican Maroons, becoming firmly entrenched in local musical culture, and Bob Marley’s work is contrasted by that of Alpha Blondy, the Ivorian performer clearly influenced by Marley and his peers. We are introduced to candomble and yemenja as cultural and spiritual practices that survived the Middle Passage, and a section on Carnival culture emphasizes that African-Caribbean cultural elements have gone on to make a huge impact in Britain. Since the overall focus is on West Africa, such elements could easily have been overlooked, and thankfully the inclusion of one of Ray Mahabir’s costumes, along with film and audio clips, reminds of Carnival’s vibrant and dazzling appeal.

[caption id="attachment_26906" align="alignnone" width="640"] Carnival costume designed by Ray Mahabir of Sunshine International Arts in 2015, based on Bele or Bel Air, a drum dance and song closely linked to Caribbean history, struggle, freedom and celebration. On display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, photographed by Toby Keane[/caption]

Moving up to the “Speaking Out” section, which looks at dissent in the late colonial era, there are iconic books by figures involved in African freedom struggles, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Sekou Toure and Amilcar Cabral, as well as a prison letter from Ken Saro-Wiwa. There is a stunning 1968 painting by the Nigerian artist, Prince Twins Seven Seven, and some lovely Bembeya Jazz and Syliphone LPs from Guinea. Then we reach the Fela room, a fitting tribute to the maverick Afrobeat pioneer who put his life on the line by perpetually challenging Nigeria’s corrupt political leaders, with eight of his albums prominently displayed, along with a castigating letter he wrote to military dictator Ibrahim Babangida in 1989. Oddly, the film clip displayed is from the recent Finding Fela, a behind-the-scenes look at the Fela musical; there are more pertinent film sources to draw from out there, so I’m not sure where Finding Fela features, but no doubt there was a practical reason behind the choice of footage. There is also a 1954 pamphlet on woman’s rights, written by Fela’s mother, Funmilayo; nearby, clips of Rokia Traore performing “Manian” and Oumou Sangare singing “Dugu Kamalenga” remind that African female artists continue to strive for gender equality in the region.

[caption id="attachment_26911" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Carnival costume designed by Ray Mahabir of Sunshine International Arts in 2015, based on Bele or Bel Air, a drum dance and song closely linked to Caribbean history, struggle, freedom and celebration. On display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, photographed by Toby Keane[/caption]

Moving up to the “Speaking Out” section, which looks at dissent in the late colonial era, there are iconic books by figures involved in African freedom struggles, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Sedar Senghor, Sekou Toure and Amilcar Cabral, as well as a prison letter from Ken Saro-Wiwa. There is a stunning 1968 painting by the Nigerian artist, Prince Twins Seven Seven, and some lovely Bembeya Jazz and Syliphone LPs from Guinea. Then we reach the Fela room, a fitting tribute to the maverick Afrobeat pioneer who put his life on the line by perpetually challenging Nigeria’s corrupt political leaders, with eight of his albums prominently displayed, along with a castigating letter he wrote to military dictator Ibrahim Babangida in 1989. Oddly, the film clip displayed is from the recent Finding Fela, a behind-the-scenes look at the Fela musical; there are more pertinent film sources to draw from out there, so I’m not sure where Finding Fela features, but no doubt there was a practical reason behind the choice of footage. There is also a 1954 pamphlet on woman’s rights, written by Fela’s mother, Funmilayo; nearby, clips of Rokia Traore performing “Manian” and Oumou Sangare singing “Dugu Kamalenga” remind that African female artists continue to strive for gender equality in the region.

[caption id="attachment_26911" align="alignnone" width="640"] Fela Kuti LP cover, Sorrow Tears and Blood[/caption]

The section labeled “Symbol” has some of the most fascinating material of the entire exhibition. We are shown the 2000-year-old Tuareg Tifinagh alphabet, some cowrie-shell letters from 1888, the Vai alphabet from the same period, and the Bamum or Shumom secret script from colonial Cameroon of the 1930s. We learn that the figure of a crocodile can have many meanings, with the example of a two-headed crocodile from Ghana denoting either conflict or collaboration. We are reminded of ways in which drums can talk, and that whistles and horns may also convey messages, and along with examples of millet-pounding songs, we see some hilarious-looking Nigerian and Ghanaian pamphlet texts, such as Life Turns Man Up and Down. A section of beautiful Ghanaian cloths also hold hidden meanings, with an eye-studded design apparently denoting the proverb, “Your eyes can see what your mouth cannot say,” meaning that not every topic is fit for discussion in public. There is cloth depicting the Ghana Guinea Worm Eradication Programme of 1989, and some lovely Aso Oke wedding cloth, as well as another that symbolically states, “Ask questions before you marry.”

[caption id="attachment_26915" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Fela Kuti LP cover, Sorrow Tears and Blood[/caption]

The section labeled “Symbol” has some of the most fascinating material of the entire exhibition. We are shown the 2000-year-old Tuareg Tifinagh alphabet, some cowrie-shell letters from 1888, the Vai alphabet from the same period, and the Bamum or Shumom secret script from colonial Cameroon of the 1930s. We learn that the figure of a crocodile can have many meanings, with the example of a two-headed crocodile from Ghana denoting either conflict or collaboration. We are reminded of ways in which drums can talk, and that whistles and horns may also convey messages, and along with examples of millet-pounding songs, we see some hilarious-looking Nigerian and Ghanaian pamphlet texts, such as Life Turns Man Up and Down. A section of beautiful Ghanaian cloths also hold hidden meanings, with an eye-studded design apparently denoting the proverb, “Your eyes can see what your mouth cannot say,” meaning that not every topic is fit for discussion in public. There is cloth depicting the Ghana Guinea Worm Eradication Programme of 1989, and some lovely Aso Oke wedding cloth, as well as another that symbolically states, “Ask questions before you marry.”

[caption id="attachment_26915" align="alignnone" width="640"] A gold weight in the shape of a two-headed crocodile made in Ghana and used for weighing gold dust, made c 18th – 20th century and on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. The crocodile symbolizes cooperation and interdependence.[/caption]

Then we head into the pertinent “Story Now” section, looking at the post-independence period. Here we find Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor collaborating with Marc Chagall in 1973 (following Chagall’s 1971 Dakar exhibition), and the Atoka photo-play magazine, produced in Nigeria in the 1970s. There is a fantastic aluminium relief by Asiru Olatunde from 1968, showing the legend of the Igbo raid on Moremi, and there is footage of Chinua Achebe speaking at the ICA in 1986, as well as his letter to Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey, and a commemorative cloth of Achebe’s literary landmark, Things Fall Apart. Other prominent post-colonial authors included in this section are Ama Ata Aidoo, Ousmane Sembene and Wole Soyinka, while the role of the Mbari Mbayo Club and its magazine, Black Orpheus, in stimulating the Nigerian literature of the pre- and post-independence periods is also featured.

[caption id="attachment_26907" align="alignnone" width="640"]

A gold weight in the shape of a two-headed crocodile made in Ghana and used for weighing gold dust, made c 18th – 20th century and on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. The crocodile symbolizes cooperation and interdependence.[/caption]

Then we head into the pertinent “Story Now” section, looking at the post-independence period. Here we find Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor collaborating with Marc Chagall in 1973 (following Chagall’s 1971 Dakar exhibition), and the Atoka photo-play magazine, produced in Nigeria in the 1970s. There is a fantastic aluminium relief by Asiru Olatunde from 1968, showing the legend of the Igbo raid on Moremi, and there is footage of Chinua Achebe speaking at the ICA in 1986, as well as his letter to Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey, and a commemorative cloth of Achebe’s literary landmark, Things Fall Apart. Other prominent post-colonial authors included in this section are Ama Ata Aidoo, Ousmane Sembene and Wole Soyinka, while the role of the Mbari Mbayo Club and its magazine, Black Orpheus, in stimulating the Nigerian literature of the pre- and post-independence periods is also featured.

[caption id="attachment_26907" align="alignnone" width="640"] Cloth commemorating Chinua Achebe on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. Nigeria, c.2013.[/caption]

Past a circular hut that forms a kind of communal reading space, there’s a final section on the present and future of the region too, with some shocking Nollywood posters for films like My Virginity, My Pride, and clips of contemporary authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Sefi Atta and Lanrewaju Adepoju reading their work.

When you find yourself back in the book shop, the most obvious thing to do is obtain a copy of the companion photo book produced for the exhibition, edited by Gus Casely-Hayford, Janet Topp Fargion and Marion Wallace. The book teases out the themes explored in the exhibition, providing much cultural and historical context behind what is on display. Though always kept accessible for the general reader, the book provides a lot of further food for thought, and I particularly enjoyed Insa Nolte’s chapter on religion; the chapter on the trans-Atlantic crossings of word and music by Fargion, Wallace and Lucy Duran; and Casely-Hayford’s opening chapter on West Africa in precolonial times.

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, succeeds partly because it is so full of surprises. It offers different ways of thinking about the region’s history, evolution and popular culture, yet leaves room for the audience to draw their own conclusions. Exhibitions on Africa are typically somewhat uncommon and ones of such wide scope far less so; related events, such as the Felabration Afrobeat night staged to coincide with the exhibit’s extended opening hours, also makes clear that the viewpoint is not an elitist one. The exhibit, at the British Library, London, until Feb. 16, 2016, is a must-see for anyone who has the opportunity to experience it.

Cloth commemorating Chinua Achebe on display in West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song. Nigeria, c.2013.[/caption]

Past a circular hut that forms a kind of communal reading space, there’s a final section on the present and future of the region too, with some shocking Nollywood posters for films like My Virginity, My Pride, and clips of contemporary authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Sefi Atta and Lanrewaju Adepoju reading their work.

When you find yourself back in the book shop, the most obvious thing to do is obtain a copy of the companion photo book produced for the exhibition, edited by Gus Casely-Hayford, Janet Topp Fargion and Marion Wallace. The book teases out the themes explored in the exhibition, providing much cultural and historical context behind what is on display. Though always kept accessible for the general reader, the book provides a lot of further food for thought, and I particularly enjoyed Insa Nolte’s chapter on religion; the chapter on the trans-Atlantic crossings of word and music by Fargion, Wallace and Lucy Duran; and Casely-Hayford’s opening chapter on West Africa in precolonial times.

West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song, succeeds partly because it is so full of surprises. It offers different ways of thinking about the region’s history, evolution and popular culture, yet leaves room for the audience to draw their own conclusions. Exhibitions on Africa are typically somewhat uncommon and ones of such wide scope far less so; related events, such as the Felabration Afrobeat night staged to coincide with the exhibit’s extended opening hours, also makes clear that the viewpoint is not an elitist one. The exhibit, at the British Library, London, until Feb. 16, 2016, is a must-see for anyone who has the opportunity to experience it.