We don’t hear a lot of music from Mozambique. There have been some fine releases of classic marrabenta dance music, and a few roots-pop bands like Ghorwane, Eyuphuro and Mabulu all produced memorable CDs in their times. There’s a Rough Guide survey of the country’s, mostly older, music. Then there are a number of releases of mind-bending Chopi timbila (wooden xylophone) orchestras, by the likes of Venancio Mbande. Probably the best introduction to Mozambican traditional music is still GlobeStyle’s two-volume series, recorded in 1989, when that country’s debilitating civil war was still simmering. But none of these releases really take stock of the musical country that has been emerging in the wake of that long war.

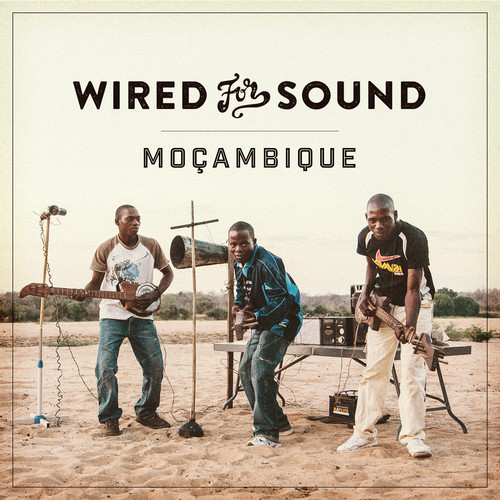

That’s what makes Wired For Sound: Mozambique a prized new entry in the small catalogue of Mozambique recordings. A team of three young musician/producers associated with the South African pop band Freshlyground and the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA)--Simon Attwell, Freshlyground guitarist Julio Sigauque and radio producer Kim Winter--traveled through Mozambique in 2013 and recorded artists they met using a 4x4, solar-powered mobile studio. They recorded little-known or unknown musicians in often remote locations, particularly in the north, where travel is not easy. You can visit the Wired For Sound website to find details on locations and artists, and to hear additional recordings.

The 17 tracks on the resulting CD present a charming, eclectic amalgam of spontaneous performances, many of them folksy, even raw, though there is room for a tough-minded rap-rock number, “Domestic Violence,” tracked by then high-school students Mdy-k Raisse O Tesouro and Flay C Gazua Gazua. These surprisingly polished artists take influence from Lusophone African hip-hop, and show an admirable keenness to engage with serious issues facing their country.

Many of the artists here are young, but that does not automatically mean they are drawn to technology or hip-hop aesthetics. Sozinho Ernesto K. Banda, or just Banda, references marrabenta, zouk love and reggae on “Takunha Dilani,” where silky smooth production showcases pleasingly rough-edged voices. Banda too is interested in addressing serious subjects: HIV, unemployment, freedom of expression.

Mateus Mapinhane Charles, from Manica province, near the border with Zimbabwe, is an aspiring singer/bandleader whose sound owes much to Zimbabwean sungura—more or less the country & western or rockabilly music of southern Africa, and still the biggest-selling pop music in Zimbabwe. The track here, “Mazano,” bridles with crunchy electric guitar figures, warm vocal harmonies, and a giddy dance beat, though it verges into a power-rock bridge just to keep listeners on their toes. That sort of easy playfulness is one of the great charms of this collection. You don’t know where it’s going next. A world without a well-functioning music industry is also a world without formulas—a distinct upside. The John Issa Band, hailing from near the remote Niassa Nature Reserve, delivers an even rawer, rural electric sound with jerry-can drums, brake cable strings, and homegrown guitar distortion.

To give a sense of the variety here, there is folksy, acoustic guitar, three-chord gospel music from Million Isaac Junior (“Thikukulola”), and sunny choral gospel music from Minesterio Envajelico De Mbonje—Mbonje is the capital of Pemba, an island of Mozambique’s southern coast. There’s a charming, palmwine-esque folk ditty in English, “Marry Very Well” by Academico and Pimento, a young vocal duo also from Pemba. Modesto, a young singer from the Tete region, channels marrabenta with a distinctly Lusophone feel on “Lavu Yu Dzuna” which features sweet guitar interplay, and a smooth voice tinged with roughness and the melancholy of a singer forced to work in agriculture, because music doesn’t pay. Melancholy mixed with merriment is a unifying characteristic here, cutting across genres, as in the case of Atija, from Nampula in the north, who offers a wistful shoutout to other Lusophone countries—Angola, Cabo Verde, São Tome, Guinea Bissau, Brazil—on “Palopes.”

It’s worth noting that the Wired For Sound producers are not folklorists documenting music as they find it. They are musicians who participate with overdubs of polished guitar work, meandering flute, or a pensive trumpet line, as Lee Thompson adds to a traditional Pankwe harp piece “Chuva,” by Liquissone Juliasse Nhamataira. Some listeners may feel this takes away from the collection’s “authenticity,” but that’s a mistake. In our increasingly homogenized, globalized musical world, kudos to young musicians who go exploring, instruments in hand, open to the stunning musical diversity that still exists off so many beaten tracks.