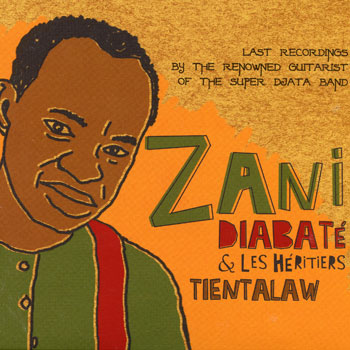

The late composer/bandleader/guitarist Zani Diabaté might lack the name recognition of Malian luminaries like Oumou Sangaré, Ali Farka Toure, Habib Koite and Toumani Diabaté, but he belongs in their company. In fact, Zani produced one of the first Malian records to make waves around the world. The Super Djata Band rocked France in 1985 with its incendiary mix of percussion, guitar and vocals adapting pentatonic music traditions of southern Mali: the Wassoulou and Kénédougou regions. Zani’s blazing electric guitar riffs—animated by his boyhood history as a percussionist, balafonist and dancer—electrified ears unaccustomed to Malian instrumental virtuosity. And the band’s lead vocalist, Flani Sangaré, had one of those voices that just tears down to your soul. When the album was released internationally as one of the first titles on Chris Blackwell’s Mango imprint in 1988, the African music surge in the US was officially underway.

Fast forward to 2010 and we find Zani as the last surviving principle member of the Super Djata Band. But he has a new combo, Les Héritiers—literally “the heirs”—made up of his own son, and the sons of Flani and singer Alou Fané. The old man went into the studio in Bamako with these young musicians and recorded the twelve terrific tracks on this CD. Unfortunately, guitar in hand in a Paris studio at the end of 2010, Zani suffered a stroke, and soon died. So Tientalaw becomes his unplanned swan song

Despite the sad surrounding story, the album is a joy. It reprises the essential magic of The Super Djata Band, but enhanced with richer call-and-response vocals, denser guitar mixes, prominent balafon (played spectacularly by Amadou Koita), and tasteful insertions of brass. “Ni Zani Mana,” a mid-tempo juggernaut, captures the classic Djata sound, especially after a mid-song jump to double time, setting up an artful solo from Zani—the song’s subject—more expressive than technical, but laced with precise ornamentation. You can’t get enough of Zani soloing, but the moments we do get really stand out. On “Djiri Djala,” he bursts out with raw clusters of notes—brief but devastating—the style picked up and personalized by the also-late Lobi Traoré.

“Komi Mana Diya” unfolds over a deep Wassoulou lope, with half-spoken hunter’s vocals by Alou “Baden” Sangaré (Flani’s son) on lead vocal, and Harouna Samaké (of Sali Sidibe and Salif Keita fame) ripping on kamelen ngoni. On “Koronto,” a rare major-key song in this mix, Harouna and Baden return, Baden echoing his father’s memorable vocal melismas. More spare is “Nikoyi” featuring deep-toned balafon and Zani’s guitar and searing vocals over a spare, ruminative rhythm section—just bass and a shaker. When the song lifts into high tempo and the balafon starts racing, your heart will as well.

The album offers a variety of arranging ideas, tempos and textures, but also tremendous coherence, and no real weak spots. This is a proud ending to a brilliant and under-recognized career.