Algerian singer-songwriter Souad Massi has charted a singular course through Arab popular music and, since she moved to Paris in 1999, world music. A poet, a thinker, a sometimes rocker with a taste for classical music, Andalusian history, and African pop, she has recorded five remarkable albums that incorporate a vast array of musical styles and thematic moods. Her 2010 release, Ô Houria (Liberty), arrived just months in advance of the Arab Spring, prescience that paved the way for two major Middle East/North Africa tours in 2011.

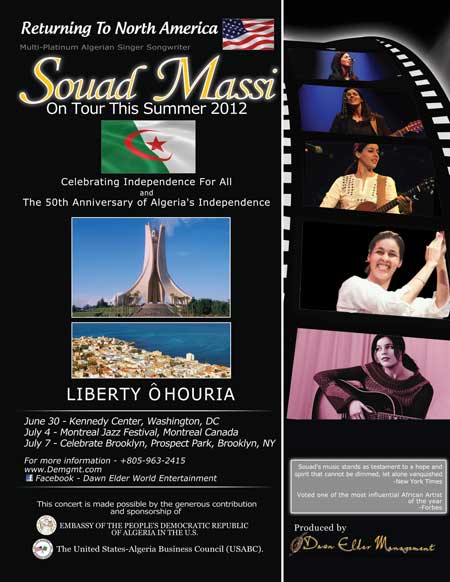

Massi’s fluid, silky voice is by turns caressing and gusty, and she is always reaching out in new directions for musical and lyrical inspiration. As Massi prepares for her first North American tour since 2004—including Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, on June 30, and Celebrate Brooklyn in New York on July 7—Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached her by phone in Paris. Here’s their conversation, with photographs from Massi’s performance at the 2011 Mawazine festival in Rabat, Morocco.

Banning Eyre: Souad, nice to speak with you again. The last time I saw you was in Rabat, Morocco, at the Mawazine Festival. We didn't speak, but I loved your concert. Your band is spectacular. But I understand that recently you have also been working with some different musicians, exploring flamenco and Andalusian music. Tell me about that.

Souad Massi: Well, I have still got my regular group. We tour all the time. But at the same time, in parallel, I am working with a flamenco guitarist named Eric Fernandez. Together we a group called Choeurs de Cordove (Voices of Córdoba), after the city of Córdoba. The inspiration was Córdoba. We launched a project, and so far we've had great reception. We've toured little in France and a little bit outside. I've always loved flamenco, and also the singing of Andalusian music. So I'm putting them together.

B.E.: Have you composed new songs for this project?

S.M.: Yes, of course. We have created a lot of new songs. Some of them are homages to a lot of poets. Of course we speak about Córdoba, and about the great poets and thinkers of Andalusia, people like Ibn Zaydún, for example. I sing some of his poems in the repertoire. It's really an homage to the great writers of the ninth, 10th, and 11th centuries in Córdoba.

B.E.: We've explored this music in a three-part series on our radio program, and we are very interested in that history. The music is beautiful.

S.M.: That's great. It's very rich. For anyone who wants to do the research, there's a lot of inspiration there.

B.E.: And it's not well known.

S.M.: Well, that depends. I have found at these concerts that people already know some of this repertoire and literature. I've really been surprised how many people have delved into this history. At least in France.

B.E.: Right, it's a little different here. In France it’s better known. And in Algeria too, since a lot of the Andalusian artists went there when they were driven out of Spain. How does Andalusian music fit into the picture in Algeria?

S.M.: In Algeria? Yes, we have Andalusian music. There is traditional Algerian music, Sha'bi music—that's the traditional singing of Algeria. There is rai. It's a big country. So it's very, very rich in music and rhythms. There's the music of the Tuareg in the South. And you have Berber music. And then there's the music of the East, Chaoui music, another language, and another tradition. The Andalusia and music of Constantine is very well-known. For those who want to look into things, and findings, it's very, very rich. There is everything.

B.E.: And you grew up with all of that.

S.M.: I was very lucky, because I grew up in a family that listened to traditional music, classical music, Universal music, but they also listened to James Brown for example. All that was in my family. My parents were already very open people. They let us listen to any music we wanted. For me, as a woman, it was a little difficult, for sure, in the society in general. But on the other hand if you don't fight, you don't get anything.

B.E.: I recall that you had difficulty when you started performing in rock bands and the like. But it seems you were very lucky to have such open parents, who introduced you to so many things at a young age. I want to come back to this Andalusia project, Choeurs de Cordove, for a moment. Aside from the music, is there a larger message in your focus on this region and this history?

S.M.: For sure. For sure. I talk about the message at the beginning of each concert.

What I love about the town of Córdoba is that the 10th century, this was the capital of culture for the world. That was in the 10th century. I learned about this, and I'm very proud of the intelligence of people of different sorts, Jews, Muslims, Christians, even atheists, and who worked together. They were doctors, writers, translators, jurists, artists, people of different backgrounds and different religions, and together they made an evolution of culture. That was how the city developed. And we in our group are also a mix of Muslims, Jews, atheists, Armenians, French, gypsies, Arabs. And there you are. The message is there. Why can't we in our time do the same thing that was done in the 10th century? That's the message. And it's the truth.

B.E.: A powerful message. And you have all those people in your group. Is it a big group?

S.M.: We are nine on the stage. You can see us on the Internet if you like, on Facebook or YouTube. Just enter Choeurs de Cordove. Voices of Córdoba.

B.E.: It sounds great. I hope one day you are able to bring this project over here to the US.

S.M.: I would love that. It's different. Some people wonder whether audiences in America would like it. It's very different. There is Spanish music in it, but also classical music in Arab music. It's very very mixed.

B.E.: I know that there are interesting groups that try to re-create the music of Andalusia. It requires imagination. Because of course we have no recordings, and no notation. But it's beautiful with they've done. And I'm really glad that you're entering into that world.

S.M.: I adore flamenco. And I adore folk. These are different worlds, but I refuse to choose between them.

B.E.: You don't have to.

S.M.: Yes, I'm free in my mind. If I want to hear flamenco, I work on flamenco. If I wanted to rock. I take my guitar and I play rock. It's good to be free.

B.E.: Let's come back to your group. I guess you're working on new music now. But I want to talk about this 2010 release, Ô Houria, Liberty. I know you made this record before the great events of the Arab world in 2011, but what was the idea in the beginning when you made it?

S.M.: Listen, I read a book by the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun. He wrote an introduction to his work, and frankly, I had not had access to this kind of philosophical literature, something I regret. But now nothing prevents me. I can read what I want. But the book really astounded me with the dimensions of this man's intelligence. He was a great thinker, and really a visionary.

B.E.: Also a great traveler. He saw so much of the world.

S.M.: Yes, yes. Ah, you are well-informed. I was really charmed by his intelligence. You know, in the beginning, when you're young, you are impressed with people who are superstars are millionaires. But now, when I read something like this, or when I meet people who are very intelligent or visionary, I'm impressed. And Ibn Khaldun, when I read this book, I understood a lot of things. There are other personalities like this who have inspired me a lot, but him, when I read his book, I saw so many things. He spoke about the changes in the world, the mentality that people had, and wanted, how individuals were demanding their rights. The struggles of people. In fact, he analyzed so many things. And there was something I imagined that there could be a great change in the Arab world. It's true that this was something that just stayed in my imagination, but there are many things that can prevent us from seeing what is possible.

But then it came. I can't say that everything that happened was good, because many people died. Sadly. But it is good to read the books of visionaries, and people who are really informed about their situation.

B.E.: And this inspired you when you were making that 2010 album?

S.M.: For me, yes, I wanted to write songs about freedom.

B.E.: And when the uprisings of 2011 began, after this record came out, what did you think? There is a certain harmony between the spirit of this record of what happened, right?

S.M.: Yes, after these things happen, I did a lot of interviews where people said I had seen

something that was going to happen, and friends of mine said the same. But really, I was surprised, first of all. At the same time, this is something very unusual, when you sing a song and then the thing happens afterwards, that's very rare. I can’t say that happens all the time. But at the same time, I think that what happened is some we have to really think about. Each case is different, and I can't say I really know what is happening in some of these countries. Things don't arrive just like that. There's a lot of work to be done. Do you understand what I'm saying? It's too soon to know, especially now.

B.E.: Yes, especially now. So, with your own group, are you now in the process of making new songs?

S.M.: Listen, just today, I was in the studio working on a demo. These are the first songs of a new album. What I do is I make demos, and then I bring in the musicians to work on songs. In the writing, I make the songs very rough. I like to be alone to write, all alone. And then I work with the group to do the arrangements and I need their participation.

B.E.: In the new songs you are writing, is there any sort of thought or reflection on these events in the Arab world?

S.M.: Well, there is an old poem, it's not mine, but it's one that I'm bringing back that talks about these things. In fact, I'm going in artistic direction where I'll use poems written by others, and set them to music. I read a lot, a lot of great philosophers and poets. I love to work with their poetry.

B.E.: We spent a month in Cairo last summer, and met a lot of musicians. I stayed in touch with some of them, and I get the feeling that it's hard for them to know what to sing about right now. It's a difficult moment, because it's sort of unclear where things are going, and what needs to be said.

S.M.: Yes. When you talk about someone who is powerful, like a politician, or even an artist who is well known internationally, there is a certain power, and you have to be very careful with your discourse. Because the words, the discourse will affect those who want to follow. So you have a responsibility. What is best for an artist is to have a universal message, like a message of peace. That is good. Afterwards, yes, it's important to sing about liberty, about revolution, and to denounce dictators, and to work for rights. Of course, every artist has his way of writing. That's important. But for me, when I go, for example to Egypt, they don't know my songs. But some of my songs are very engaged, and I never had problems before the revolution, or now.

B.E.: I understand you've been touring recently in the Middle East, and the Gulf. Where have you been?

S.M.: I've made two Middle East tours. We've been in Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Ramallah, other countries too. Lebanon.

B.E.: Do you feel a difference in the response of the audiences now?

S.M.: Yes. Yes. There is a difference. The reaction of people is different. Throughout the Arab world, people understand about 85% of what I say. So we communicate. If I talk about a girl who can't go out the house because of tradition, Arab women discover themselves and that song. It's something that concerns them, for example. I can understand my language.

B.E.: I noticed when I saw the group in Morocco that the sound on stage was somewhat different than the record. The record is very relaxed and beautiful. On stage, you have the feeling of rock 'n roll. A lot of energy.

S.M.: Yes, yes, happily. You know when you start writing songs come afterwards

they really come to life on the stage. They grow, they change, they evolve. There are a lot of artists who tour the songs before they record them. That's a nice thing to do. It's good to do that, because you have time to explore the songs and let them grow. Me, I do the opposite, record them in the studio and then I take them on tour. Maybe I'll change someday. I'll have to see. But what I can say is when the songs are new, they're like a baby. I'm not sure I want to expose them right away. I like to protect them, let them grow up, before I let people hear them.

B.E.: Maybe you have to do a live record so you can introduce the songs as adults.

S.M.: Yes. Yes.

B.E.: Your group is wonderful. I've seen you perform a few times, and I'm always impressed. It has some interesting conversations with your guitarist. He's excellent.

S.M.: Well, we've been friends for 10 years. All that time, the same team. We have fun together. We amuse each other. That's important. If you have problems among the musicians, it affects the music.

B.E.: Yes. And you feel that on the stage. You guys have real chemistry. The only way you get that is through experience.

S.M.: Yes. We feel that from the people too. It's important. We make mistakes. That's normal. True. But it's no problem.

B.E.: I know that when you tour this time, it's going to be the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence. Is that some you think about?

S.M.: Absolutely. It's important. It's important because Algeria is a country that suffered a lot with war. They were millions of people who died during that war. My mother's whole family was killed during the war. So I respect their lives, their choices, their sacrifices. It's very sad to lose your family. So for me it is important. It's important to talk about history. It's important to know your history. If you don't hold onto these things, you won't know what happened afterwards.

B.E.: So even though you live in France, your connection to Algeria remains strong.

S.M.: Yes, it remains strong because I grew up in Algeria, I did my studies in Algeria. I sing in Arab. I'm always in contact with my family, and I read the press from Algeria. So I stay in touch. It's still my home.

B.E.: And you go there to perform?

S.M.: Yes. I hope to go again soon. I've been waiting for these elections to be over. I have a lot of fans who want to see me.

B.E.: When was the last time you played there?

S.M.: It was about two years ago.

B.E.: I read that the election went peacefully. That's good.

S.M.: Yes. Happily. Algeria—I always tell people that it's not like the other countries in the region, like Egypt or Tunisia. I mention those countries because I know them a little. We already had the right to express ourselves. We have plenty of newspapers that denounce things going on with the government. It's not the same as in those other countries. We had quite a lot of stability. Of course, we do lack certain things. We were very much traumatized by our Civil War. We don't want to go back to that. The people of Algeria had enough of that. Most of the people I speak with they want to move ahead. They don't want to live in suffering and division. I think there are moments for really looking at what you want to do and what you want to win.

B.E.: I understand that you are going to star in a film by the Palestinian director Najwa Najjar. Tell me a little bit about that.

S.M.: Well, it's a film that takes place in Ramallah. It's about a Palestinian who falls in love with an Algerian woman. I think that's why they chose me to play that part. It talks about war and love. Happily it's more about love than war. It's a little bit funny. We will be starting to film on August 20.

B.E.: This is the first time you will act in a film?

S.M.: Yes. This'll be the first time. The director saw me on stage and said, "You look good.

Your personality. You look like my character." But it's something else, with the camera. It will be another experience. But I have confidence that it will work out.

B.E.: Did you do in a theater when you are young and Algeria?

S.M.: No, no. Not at all. I just did music, never theater. Frankly I don't know how this will go. But I figure, why not?

B.E.: It's a new adventure.

S.M.: Well, I'm going to do it, and we'll see afterwards. You never know, but I'm going to try.

B.E.: Are there other new developments in your career that we should talk about?

S.M.: I don't know. I'm starting to work on the new album. You're the first person I've told that, because I just started today. I just started writing new songs. So far I'm very happy. We will be playing festivals this summer. And I'm looking forward to it returning to the American public, because it's a super audience.

B.E.: And it's too long since you've been here.

S.M.: Thank you.

B.E.: Now what about the Voices of Córdoba? Will you record a record?

S.M.: Yes, yes, yes. Universal is interested in having us record. It's in process. I think we will probably record in September.

B.E.: That's great. I think this new project is really going to expand your persona as a musician.

S.M.: The problem is I would also like to grow the ensemble, with violin, and the guitars, and all these things, but the problem is it's very difficult to tour. We don't have enough of a budget. The ideas are there, but it's difficult.

B.E.: Well maybe it won't be able to tour a lot, but it will be something you can present a special concerts, or on television, and in recordings.

S.M.: Yes, this is what I say. We might not tour very much. This will be something for people who love literature and theater. It might be more for intellectuals and so on. You understand?

B.E.: Sure. And even if people only experience it through videos and recordings, they will see that you're making new connections with history and literature. It's not so many pop musicians who do things like that.

S.M.: That's true. Frankly, I've been very lucky. You know if you read, and you travel.... For me, in discovering Córdoba was something new. I saw it, and thought it was beautiful. Afterwards, I started researching on the Internet, and in libraries. I found books. I spoke with friends. And then we started playing like this at home, and that led to composing. At first it was just among friends, in Italy. Then we set up some dates, pictures, videos. It grew. By now, we've worked very hard on this project.

B.E.: I am happy to hear about this. I look forward to of hearing more. Coming back to your return to the United States, you know that when you play in Brooklyn, it will be our Independence celebration as well. You're playing over the Fourth of July weekend. So will celebrate together.

S.M.: The Fourth of July. That's great. That's great.

B.E.: In the venue where you'll be performing, Celebrate Brooklyn, is one of the best stages in New York. It's beautiful, free to the public. All is a very diverse crowd shows up. You'll love it.

S.M.: Very good. I am happy to hear that.

B.E.: Thank you, Souad. See you in Brooklyn.