Blog September 14, 2016

Remembering Prince Buster: The Passing of A Jamaican Music Legend

Jamaican singer and producer Muhammed Yusef Ali, known to his fans as Prince Buster, passed away in Miami on Sept. 8. A pivotal figure in the early development of Jamaican popular music, his recording career spanned the 1950s and ‘60s, and coincided with the rise of ska, rocksteady and early reggae; and his innovations helped chart the course of all three. He enjoyed particular success in the U.K., and benefited from a resurgence there during the ska revival in the late ‘70s. Ali was admitted to Memorial Regional Hospital in Miami on Tuesday and died there early last Thursday morning. He is survived by his wife, Mola Ali, their 19 children, and numerous grandchildren. He was 78 years old.

Ali was born Cecil Bustamente Campbell, on May 24, 1938 on Orange St. in the then-commercial and cultural heart of Kingston, Jamaica. Campbell’s musical career began early, performing weekly at Kingston’s Glass Bucket club while still in secondary school in the 1950s. He acquired his nickname “Prince” as a young boxer, training with Jamaica’s middleweight champion Sid Brown (“Buster” came from a shortening of his middle name, a tribute to Jamaican labor leader and first prime minister, Alexander Bustamante). His boxing skills were in demand in the sometimes violent world of the sound systems—the mobile, speaker-mounted, DJ trucks whose street parties brought many Jamaicans their music in the days before the transistor radio. Campbell worked for two of the biggest sound systems of the day: Tom The Great Sebastian’s and, later, Coxsone Dodd’s legendary “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” system.

It was under Dodd’s tutelage that Campbell worked his way up the ranks, holding down every job in the dance hall, from bouncing rowdies and collecting door receipts, to sourcing and selecting records. By the late ‘50s Campbell was running his own “Voice of the People” sound system as the new upstart in the long-established rivalry between Coxsone’s Downbeat and Arthur “Duke” Reid’s Trojan Sound.

Always ambitions and independent, Campbell wanted his own record label, too. He founded the Wild Bells label in 1961, alongside Dodd’s Studio One and Reid’s Treasure Isle. This was the first of many imprints, including his most famous, Voice of the People. As a producer, Campell was innovative from the beginning, scoring his first hit with the Folkes Brothers’ “Oh Carolina.” This infectious track featured the propulsive Nyahbinghi drumming of Count Ossie and his Rastafarian troupe from the Wareika Hill camp above Kingston. It marked the introduction of authentic Rastafarian sounds into Jamaican pop music, and would go on to become one of reggae music's most durable riddims, even scoring a number one hit in the U.K. for dancehall don Shaggy in 1993.

Many more hits would follow. As Jamaica gained its independence from the U.K. in 1962, the island’s music also found its own voice; shaking off the last vestiges of imitation American r&b in favor of the syncopated "off-beat" sound known as ska. And Prince Buster was at the forefront of this movement, both as a producer and a singer.

He made his own singing debut in 1963 and his early ’60s ska output was prolific. Songs like “Madness," “One Step Beyond," and “Wash Wash” were funny, bawdy, confrontational, defiant, and above all, supremely confident. As a vocalist, Campbell was more a talker than a singer, he turned his limited range into an asset with his almost-conversational toasting style. As Prince Buster, he created a cocky, streetwise persona that spoke in the emerging voice of post-colonial Jamaica, but told coded stories pitched to the ears of West Kingston. He injected smirking sexual innuendo, ghetto gossip, political musings, personal grudges and Black Power consciousness into his lyrics—and he brooked no dissent.

Prince Buster was the first Jamaican musician to score a hit in the U.K. with 1964’s “Al Capone." He was distributed there on the influential Blue Beat label, which helped connect the first generation of post-war Jamaican immigrants in Britain with the musical revolution happening back home. Buster was extremely popular early on in the U.K., and toured there often.

That same year he was part of Jamaica’s delegation to the World’s Fair in Queens, NY, where he performed alongside Millie Small, Jimmy Cliff, Byron Lee and others. While in New York Campbell met Muhammad Ali (Buster was a genuine fan of the newly minted heavyweight champion, and had already recorded a song dedicated to Ali), who introduced him to the Nation of Islam. Campbell converted to the faith soon after, taking the name Muhammed Yusef Ali and founding a new label, simply called Islam.

By the second half of the ‘60s, the optimism of Jamaican independence was curdling into the violence of the rude boy era, and ska’s frenetic pace cooled down into rocksteady’s slower tempo. Once again, Prince Buster kept pace with the times, releasing a brace of rocksteady classics including “Too Hot," “Rough Rider,” and introducing his most beloved character, “Judge Dread." He continued to innovate as well, as one of the few artists of the era to release full-length LPs as well as singles, and often worked with the top session musicians and engineers of the day.

Released in 1967, “Judge Dread” took on the rude boys and their street violence by way of a merciless Rastafarian judge—voiced by Buster, naturally—straight from Ethiopia who gave away 400-year sentences like candy to the rudies unlucky enough to wind up in his court. It was a stern rebuke to the rude boy craze and the dozens of records that celebrated their exploits, and was an instant hit. It also inspired a slew of answer records from other artists, most famously from Buster’s old protege and rival, Derrick Morgan, who promptly released “Judge Dread in Court," provoking one of the greatest musical beefs in Jamaican history.

But Buster’s heyday as a hitmaker was coming to a close. As rocksteady gave way to reggae at the end of the ‘60s, he no longer had the pulse of the people; and his Islamic faith prevented him from fully embracing the Rastafarian revolution that was sweeping the Jamaican music scene. Though he managed a brief cameo in Perry Henzell’s groundbreaking 1972 reggae film The Harder They Come, Buster largely sat out the reggae explosion of the 1970s. Buster did still continue to produce and record occasionally—including some memorable forays into dub—but he never again matched his prodigious 1960s output. He preferred to run his Record Shack shop on Orange St. in downtown Kingston, stocking the latest reggae records his alongside releases on his own various labels.

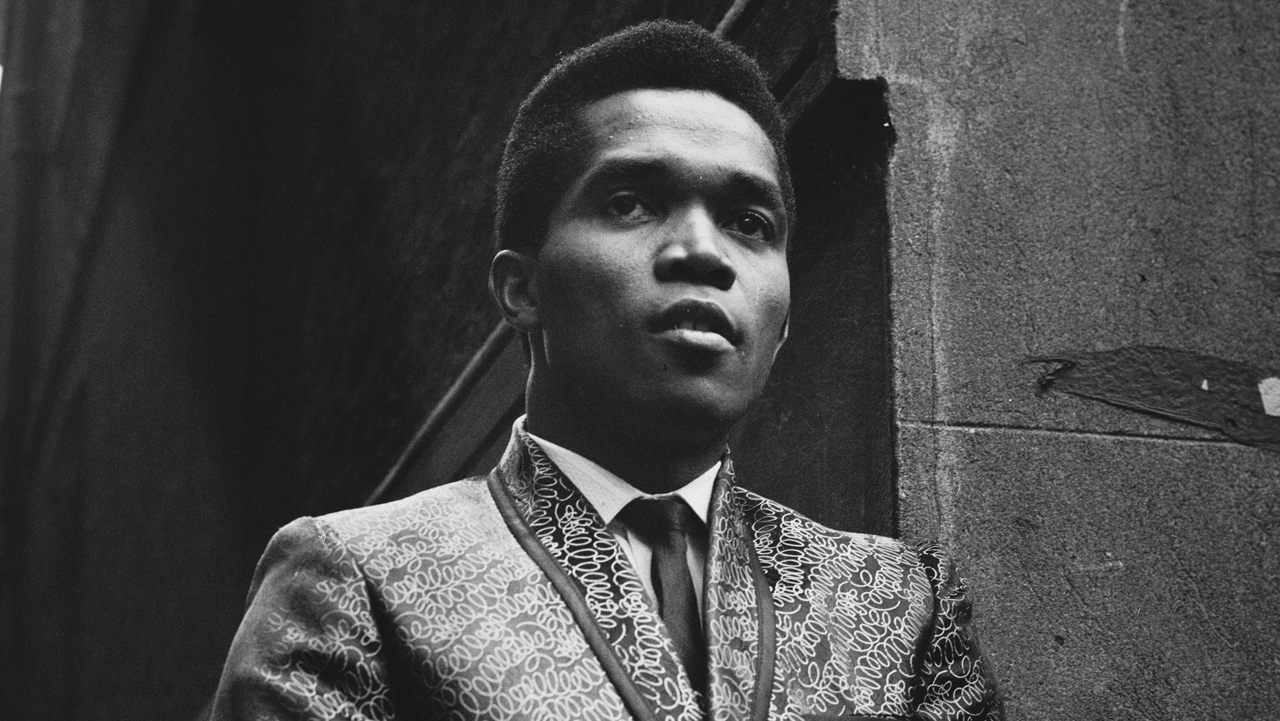

At the end of the '70s, a new generation of British musicians rediscovered Prince Buster’s catalog, thanks to the Blue Beat label, and he became an icon of the Two-Tone ska revival. Buster's vintage, mid-'60s look—sharply tailored mod suits, stingy-brim hats and skinny ties—helped provide the visual template for a new ska craze in the U.K., and his music provided the soundtrack. Bands on and off the Two Tone label roster—Madness, the Specials, Bad Manners and the English Beat—all recorded cover versions of Buster’s 1960s hits. Madness had the most success, cracking the British Top 10 in 1979 with their cover of Buster’s 1964 hit, “One Step Beyond."

In the subsequent decades, Buster settled comfortably into the role as an elder statesman for the “Foundation Generation” of Jamaican music. He was awarded the Order of Distinction (O.D.) by the Jamaican government in 2001, and basked in his new nickname “The King of Ska." He continued to perform his catalog of ska and rocksteady hits at festivals and special appearances worldwide until he was sidelined by a stroke in 2009.

Prince Buster's passing last Thursday was noted everywhere from Jamaica's Gleaner newspaper to Time magazine, and many of the musicians that he inspired took to social media to mourn his passing; the band Madness dedicated their set at the BBC2 Radio Days festival in London's Hyde Park to Buster on Sunday.

Ali was born Cecil Bustamente Campbell, on May 24, 1938 on Orange St. in the then-commercial and cultural heart of Kingston, Jamaica. Campbell’s musical career began early, performing weekly at Kingston’s Glass Bucket club while still in secondary school in the 1950s. He acquired his nickname “Prince” as a young boxer, training with Jamaica’s middleweight champion Sid Brown (“Buster” came from a shortening of his middle name, a tribute to Jamaican labor leader and first prime minister, Alexander Bustamante). His boxing skills were in demand in the sometimes violent world of the sound systems—the mobile, speaker-mounted, DJ trucks whose street parties brought many Jamaicans their music in the days before the transistor radio. Campbell worked for two of the biggest sound systems of the day: Tom The Great Sebastian’s and, later, Coxsone Dodd’s legendary “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” system.

It was under Dodd’s tutelage that Campbell worked his way up the ranks, holding down every job in the dance hall, from bouncing rowdies and collecting door receipts, to sourcing and selecting records. By the late ‘50s Campbell was running his own “Voice of the People” sound system as the new upstart in the long-established rivalry between Coxsone’s Downbeat and Arthur “Duke” Reid’s Trojan Sound.

Always ambitions and independent, Campbell wanted his own record label, too. He founded the Wild Bells label in 1961, alongside Dodd’s Studio One and Reid’s Treasure Isle. This was the first of many imprints, including his most famous, Voice of the People. As a producer, Campell was innovative from the beginning, scoring his first hit with the Folkes Brothers’ “Oh Carolina.” This infectious track featured the propulsive Nyahbinghi drumming of Count Ossie and his Rastafarian troupe from the Wareika Hill camp above Kingston. It marked the introduction of authentic Rastafarian sounds into Jamaican pop music, and would go on to become one of reggae music's most durable riddims, even scoring a number one hit in the U.K. for dancehall don Shaggy in 1993.

Many more hits would follow. As Jamaica gained its independence from the U.K. in 1962, the island’s music also found its own voice; shaking off the last vestiges of imitation American r&b in favor of the syncopated "off-beat" sound known as ska. And Prince Buster was at the forefront of this movement, both as a producer and a singer.

He made his own singing debut in 1963 and his early ’60s ska output was prolific. Songs like “Madness," “One Step Beyond," and “Wash Wash” were funny, bawdy, confrontational, defiant, and above all, supremely confident. As a vocalist, Campbell was more a talker than a singer, he turned his limited range into an asset with his almost-conversational toasting style. As Prince Buster, he created a cocky, streetwise persona that spoke in the emerging voice of post-colonial Jamaica, but told coded stories pitched to the ears of West Kingston. He injected smirking sexual innuendo, ghetto gossip, political musings, personal grudges and Black Power consciousness into his lyrics—and he brooked no dissent.

Prince Buster was the first Jamaican musician to score a hit in the U.K. with 1964’s “Al Capone." He was distributed there on the influential Blue Beat label, which helped connect the first generation of post-war Jamaican immigrants in Britain with the musical revolution happening back home. Buster was extremely popular early on in the U.K., and toured there often.

That same year he was part of Jamaica’s delegation to the World’s Fair in Queens, NY, where he performed alongside Millie Small, Jimmy Cliff, Byron Lee and others. While in New York Campbell met Muhammad Ali (Buster was a genuine fan of the newly minted heavyweight champion, and had already recorded a song dedicated to Ali), who introduced him to the Nation of Islam. Campbell converted to the faith soon after, taking the name Muhammed Yusef Ali and founding a new label, simply called Islam.

By the second half of the ‘60s, the optimism of Jamaican independence was curdling into the violence of the rude boy era, and ska’s frenetic pace cooled down into rocksteady’s slower tempo. Once again, Prince Buster kept pace with the times, releasing a brace of rocksteady classics including “Too Hot," “Rough Rider,” and introducing his most beloved character, “Judge Dread." He continued to innovate as well, as one of the few artists of the era to release full-length LPs as well as singles, and often worked with the top session musicians and engineers of the day.

Released in 1967, “Judge Dread” took on the rude boys and their street violence by way of a merciless Rastafarian judge—voiced by Buster, naturally—straight from Ethiopia who gave away 400-year sentences like candy to the rudies unlucky enough to wind up in his court. It was a stern rebuke to the rude boy craze and the dozens of records that celebrated their exploits, and was an instant hit. It also inspired a slew of answer records from other artists, most famously from Buster’s old protege and rival, Derrick Morgan, who promptly released “Judge Dread in Court," provoking one of the greatest musical beefs in Jamaican history.

But Buster’s heyday as a hitmaker was coming to a close. As rocksteady gave way to reggae at the end of the ‘60s, he no longer had the pulse of the people; and his Islamic faith prevented him from fully embracing the Rastafarian revolution that was sweeping the Jamaican music scene. Though he managed a brief cameo in Perry Henzell’s groundbreaking 1972 reggae film The Harder They Come, Buster largely sat out the reggae explosion of the 1970s. Buster did still continue to produce and record occasionally—including some memorable forays into dub—but he never again matched his prodigious 1960s output. He preferred to run his Record Shack shop on Orange St. in downtown Kingston, stocking the latest reggae records his alongside releases on his own various labels.

At the end of the '70s, a new generation of British musicians rediscovered Prince Buster’s catalog, thanks to the Blue Beat label, and he became an icon of the Two-Tone ska revival. Buster's vintage, mid-'60s look—sharply tailored mod suits, stingy-brim hats and skinny ties—helped provide the visual template for a new ska craze in the U.K., and his music provided the soundtrack. Bands on and off the Two Tone label roster—Madness, the Specials, Bad Manners and the English Beat—all recorded cover versions of Buster’s 1960s hits. Madness had the most success, cracking the British Top 10 in 1979 with their cover of Buster’s 1964 hit, “One Step Beyond."

In the subsequent decades, Buster settled comfortably into the role as an elder statesman for the “Foundation Generation” of Jamaican music. He was awarded the Order of Distinction (O.D.) by the Jamaican government in 2001, and basked in his new nickname “The King of Ska." He continued to perform his catalog of ska and rocksteady hits at festivals and special appearances worldwide until he was sidelined by a stroke in 2009.

Prince Buster's passing last Thursday was noted everywhere from Jamaica's Gleaner newspaper to Time magazine, and many of the musicians that he inspired took to social media to mourn his passing; the band Madness dedicated their set at the BBC2 Radio Days festival in London's Hyde Park to Buster on Sunday.

Ali was born Cecil Bustamente Campbell, on May 24, 1938 on Orange St. in the then-commercial and cultural heart of Kingston, Jamaica. Campbell’s musical career began early, performing weekly at Kingston’s Glass Bucket club while still in secondary school in the 1950s. He acquired his nickname “Prince” as a young boxer, training with Jamaica’s middleweight champion Sid Brown (“Buster” came from a shortening of his middle name, a tribute to Jamaican labor leader and first prime minister, Alexander Bustamante). His boxing skills were in demand in the sometimes violent world of the sound systems—the mobile, speaker-mounted, DJ trucks whose street parties brought many Jamaicans their music in the days before the transistor radio. Campbell worked for two of the biggest sound systems of the day: Tom The Great Sebastian’s and, later, Coxsone Dodd’s legendary “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” system.

It was under Dodd’s tutelage that Campbell worked his way up the ranks, holding down every job in the dance hall, from bouncing rowdies and collecting door receipts, to sourcing and selecting records. By the late ‘50s Campbell was running his own “Voice of the People” sound system as the new upstart in the long-established rivalry between Coxsone’s Downbeat and Arthur “Duke” Reid’s Trojan Sound.

Always ambitions and independent, Campbell wanted his own record label, too. He founded the Wild Bells label in 1961, alongside Dodd’s Studio One and Reid’s Treasure Isle. This was the first of many imprints, including his most famous, Voice of the People. As a producer, Campell was innovative from the beginning, scoring his first hit with the Folkes Brothers’ “Oh Carolina.” This infectious track featured the propulsive Nyahbinghi drumming of Count Ossie and his Rastafarian troupe from the Wareika Hill camp above Kingston. It marked the introduction of authentic Rastafarian sounds into Jamaican pop music, and would go on to become one of reggae music's most durable riddims, even scoring a number one hit in the U.K. for dancehall don Shaggy in 1993.

Many more hits would follow. As Jamaica gained its independence from the U.K. in 1962, the island’s music also found its own voice; shaking off the last vestiges of imitation American r&b in favor of the syncopated "off-beat" sound known as ska. And Prince Buster was at the forefront of this movement, both as a producer and a singer.

He made his own singing debut in 1963 and his early ’60s ska output was prolific. Songs like “Madness," “One Step Beyond," and “Wash Wash” were funny, bawdy, confrontational, defiant, and above all, supremely confident. As a vocalist, Campbell was more a talker than a singer, he turned his limited range into an asset with his almost-conversational toasting style. As Prince Buster, he created a cocky, streetwise persona that spoke in the emerging voice of post-colonial Jamaica, but told coded stories pitched to the ears of West Kingston. He injected smirking sexual innuendo, ghetto gossip, political musings, personal grudges and Black Power consciousness into his lyrics—and he brooked no dissent.

Prince Buster was the first Jamaican musician to score a hit in the U.K. with 1964’s “Al Capone." He was distributed there on the influential Blue Beat label, which helped connect the first generation of post-war Jamaican immigrants in Britain with the musical revolution happening back home. Buster was extremely popular early on in the U.K., and toured there often.

That same year he was part of Jamaica’s delegation to the World’s Fair in Queens, NY, where he performed alongside Millie Small, Jimmy Cliff, Byron Lee and others. While in New York Campbell met Muhammad Ali (Buster was a genuine fan of the newly minted heavyweight champion, and had already recorded a song dedicated to Ali), who introduced him to the Nation of Islam. Campbell converted to the faith soon after, taking the name Muhammed Yusef Ali and founding a new label, simply called Islam.

By the second half of the ‘60s, the optimism of Jamaican independence was curdling into the violence of the rude boy era, and ska’s frenetic pace cooled down into rocksteady’s slower tempo. Once again, Prince Buster kept pace with the times, releasing a brace of rocksteady classics including “Too Hot," “Rough Rider,” and introducing his most beloved character, “Judge Dread." He continued to innovate as well, as one of the few artists of the era to release full-length LPs as well as singles, and often worked with the top session musicians and engineers of the day.

Released in 1967, “Judge Dread” took on the rude boys and their street violence by way of a merciless Rastafarian judge—voiced by Buster, naturally—straight from Ethiopia who gave away 400-year sentences like candy to the rudies unlucky enough to wind up in his court. It was a stern rebuke to the rude boy craze and the dozens of records that celebrated their exploits, and was an instant hit. It also inspired a slew of answer records from other artists, most famously from Buster’s old protege and rival, Derrick Morgan, who promptly released “Judge Dread in Court," provoking one of the greatest musical beefs in Jamaican history.

But Buster’s heyday as a hitmaker was coming to a close. As rocksteady gave way to reggae at the end of the ‘60s, he no longer had the pulse of the people; and his Islamic faith prevented him from fully embracing the Rastafarian revolution that was sweeping the Jamaican music scene. Though he managed a brief cameo in Perry Henzell’s groundbreaking 1972 reggae film The Harder They Come, Buster largely sat out the reggae explosion of the 1970s. Buster did still continue to produce and record occasionally—including some memorable forays into dub—but he never again matched his prodigious 1960s output. He preferred to run his Record Shack shop on Orange St. in downtown Kingston, stocking the latest reggae records his alongside releases on his own various labels.

At the end of the '70s, a new generation of British musicians rediscovered Prince Buster’s catalog, thanks to the Blue Beat label, and he became an icon of the Two-Tone ska revival. Buster's vintage, mid-'60s look—sharply tailored mod suits, stingy-brim hats and skinny ties—helped provide the visual template for a new ska craze in the U.K., and his music provided the soundtrack. Bands on and off the Two Tone label roster—Madness, the Specials, Bad Manners and the English Beat—all recorded cover versions of Buster’s 1960s hits. Madness had the most success, cracking the British Top 10 in 1979 with their cover of Buster’s 1964 hit, “One Step Beyond."

In the subsequent decades, Buster settled comfortably into the role as an elder statesman for the “Foundation Generation” of Jamaican music. He was awarded the Order of Distinction (O.D.) by the Jamaican government in 2001, and basked in his new nickname “The King of Ska." He continued to perform his catalog of ska and rocksteady hits at festivals and special appearances worldwide until he was sidelined by a stroke in 2009.

Prince Buster's passing last Thursday was noted everywhere from Jamaica's Gleaner newspaper to Time magazine, and many of the musicians that he inspired took to social media to mourn his passing; the band Madness dedicated their set at the BBC2 Radio Days festival in London's Hyde Park to Buster on Sunday.

Ali was born Cecil Bustamente Campbell, on May 24, 1938 on Orange St. in the then-commercial and cultural heart of Kingston, Jamaica. Campbell’s musical career began early, performing weekly at Kingston’s Glass Bucket club while still in secondary school in the 1950s. He acquired his nickname “Prince” as a young boxer, training with Jamaica’s middleweight champion Sid Brown (“Buster” came from a shortening of his middle name, a tribute to Jamaican labor leader and first prime minister, Alexander Bustamante). His boxing skills were in demand in the sometimes violent world of the sound systems—the mobile, speaker-mounted, DJ trucks whose street parties brought many Jamaicans their music in the days before the transistor radio. Campbell worked for two of the biggest sound systems of the day: Tom The Great Sebastian’s and, later, Coxsone Dodd’s legendary “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” system.

It was under Dodd’s tutelage that Campbell worked his way up the ranks, holding down every job in the dance hall, from bouncing rowdies and collecting door receipts, to sourcing and selecting records. By the late ‘50s Campbell was running his own “Voice of the People” sound system as the new upstart in the long-established rivalry between Coxsone’s Downbeat and Arthur “Duke” Reid’s Trojan Sound.

Always ambitions and independent, Campbell wanted his own record label, too. He founded the Wild Bells label in 1961, alongside Dodd’s Studio One and Reid’s Treasure Isle. This was the first of many imprints, including his most famous, Voice of the People. As a producer, Campell was innovative from the beginning, scoring his first hit with the Folkes Brothers’ “Oh Carolina.” This infectious track featured the propulsive Nyahbinghi drumming of Count Ossie and his Rastafarian troupe from the Wareika Hill camp above Kingston. It marked the introduction of authentic Rastafarian sounds into Jamaican pop music, and would go on to become one of reggae music's most durable riddims, even scoring a number one hit in the U.K. for dancehall don Shaggy in 1993.

Many more hits would follow. As Jamaica gained its independence from the U.K. in 1962, the island’s music also found its own voice; shaking off the last vestiges of imitation American r&b in favor of the syncopated "off-beat" sound known as ska. And Prince Buster was at the forefront of this movement, both as a producer and a singer.

He made his own singing debut in 1963 and his early ’60s ska output was prolific. Songs like “Madness," “One Step Beyond," and “Wash Wash” were funny, bawdy, confrontational, defiant, and above all, supremely confident. As a vocalist, Campbell was more a talker than a singer, he turned his limited range into an asset with his almost-conversational toasting style. As Prince Buster, he created a cocky, streetwise persona that spoke in the emerging voice of post-colonial Jamaica, but told coded stories pitched to the ears of West Kingston. He injected smirking sexual innuendo, ghetto gossip, political musings, personal grudges and Black Power consciousness into his lyrics—and he brooked no dissent.

Prince Buster was the first Jamaican musician to score a hit in the U.K. with 1964’s “Al Capone." He was distributed there on the influential Blue Beat label, which helped connect the first generation of post-war Jamaican immigrants in Britain with the musical revolution happening back home. Buster was extremely popular early on in the U.K., and toured there often.

That same year he was part of Jamaica’s delegation to the World’s Fair in Queens, NY, where he performed alongside Millie Small, Jimmy Cliff, Byron Lee and others. While in New York Campbell met Muhammad Ali (Buster was a genuine fan of the newly minted heavyweight champion, and had already recorded a song dedicated to Ali), who introduced him to the Nation of Islam. Campbell converted to the faith soon after, taking the name Muhammed Yusef Ali and founding a new label, simply called Islam.

By the second half of the ‘60s, the optimism of Jamaican independence was curdling into the violence of the rude boy era, and ska’s frenetic pace cooled down into rocksteady’s slower tempo. Once again, Prince Buster kept pace with the times, releasing a brace of rocksteady classics including “Too Hot," “Rough Rider,” and introducing his most beloved character, “Judge Dread." He continued to innovate as well, as one of the few artists of the era to release full-length LPs as well as singles, and often worked with the top session musicians and engineers of the day.

Released in 1967, “Judge Dread” took on the rude boys and their street violence by way of a merciless Rastafarian judge—voiced by Buster, naturally—straight from Ethiopia who gave away 400-year sentences like candy to the rudies unlucky enough to wind up in his court. It was a stern rebuke to the rude boy craze and the dozens of records that celebrated their exploits, and was an instant hit. It also inspired a slew of answer records from other artists, most famously from Buster’s old protege and rival, Derrick Morgan, who promptly released “Judge Dread in Court," provoking one of the greatest musical beefs in Jamaican history.

But Buster’s heyday as a hitmaker was coming to a close. As rocksteady gave way to reggae at the end of the ‘60s, he no longer had the pulse of the people; and his Islamic faith prevented him from fully embracing the Rastafarian revolution that was sweeping the Jamaican music scene. Though he managed a brief cameo in Perry Henzell’s groundbreaking 1972 reggae film The Harder They Come, Buster largely sat out the reggae explosion of the 1970s. Buster did still continue to produce and record occasionally—including some memorable forays into dub—but he never again matched his prodigious 1960s output. He preferred to run his Record Shack shop on Orange St. in downtown Kingston, stocking the latest reggae records his alongside releases on his own various labels.

At the end of the '70s, a new generation of British musicians rediscovered Prince Buster’s catalog, thanks to the Blue Beat label, and he became an icon of the Two-Tone ska revival. Buster's vintage, mid-'60s look—sharply tailored mod suits, stingy-brim hats and skinny ties—helped provide the visual template for a new ska craze in the U.K., and his music provided the soundtrack. Bands on and off the Two Tone label roster—Madness, the Specials, Bad Manners and the English Beat—all recorded cover versions of Buster’s 1960s hits. Madness had the most success, cracking the British Top 10 in 1979 with their cover of Buster’s 1964 hit, “One Step Beyond."

In the subsequent decades, Buster settled comfortably into the role as an elder statesman for the “Foundation Generation” of Jamaican music. He was awarded the Order of Distinction (O.D.) by the Jamaican government in 2001, and basked in his new nickname “The King of Ska." He continued to perform his catalog of ska and rocksteady hits at festivals and special appearances worldwide until he was sidelined by a stroke in 2009.

Prince Buster's passing last Thursday was noted everywhere from Jamaica's Gleaner newspaper to Time magazine, and many of the musicians that he inspired took to social media to mourn his passing; the band Madness dedicated their set at the BBC2 Radio Days festival in London's Hyde Park to Buster on Sunday.

Rest in peace Prince Buster. & tanks fe the inspiration. With love from @NevilleStaple & @SugaryStaple https://t.co/dJHsPmkOu9

— Neville Staple (@NevilleStaple) September 8, 2016

prince buster rock steady forever

— Flea (@flea333) September 9, 2016

The Specials' founder Jerry Dammers spoke for many in his remembrance of Buster in the pages of The Guardian hailing him as "the first king of Jamaican music" and adding: "I truly believe he turned out to be among the most influential figures in late-20th century music worldwide. Myself and all the Two Tone bands owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. None of us would have had the career in music we have had if it hadn’t been for Prince Buster and his fellow Jamaican musicians." The Prince is dead. Long live the Prince.It is with great sadness that I have just learned of the death of Jamaica's music icon and pioneer, Prince Buster. A true music legend.

— David Rodigan (@DavidRodigan) September 8, 2016