Abdalla Uba Adamu is a professor of both Science Education and Mass Communication at Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria. He specializes in media and cultural education, particularly the interface between Islamic religion, Hausa culture and media—film, music and literature. When we visited Kano in February 2017, the professor was temporarily serving as vice chancellor of a university in Abuja. So we were lucky to catch him on a visit back to Kano. We met in his office, which is open to the street and frequented by students, colleagues and friends eager to get even a brief audience with this charismatic and influential man. As such we had an audience for our interview, which was most generous, lasting over two hours. Professor Adamu is a remarkable man, brilliant, charming, funny and extremely well connected. From the biggest nanaye pop singer to the most underground rappers, musicians not only defer to, but revere the professor. Here are extended excerpts from our conversation. For much more, visit http://www.auadamu.com/.

Banning Eyre: How did Indian films come to have such a big influence up here in Hausa land?

Abdalla Uba Adamu: The Hausa are very conservative, religiously. So when foreign ideas start coming in, they absorb them based on their understanding of the relationship between the foreign idea and their own idea, and how their own idea fits in with what they do. So music or literature or film that fits in with their social reality are easily accepted. And that that does not fit into their social reality is rejected. And that is why they like Indian films a lot, because the Indian films seem to capture a social reality that is closer to their own social realities. So you have some kind of resonance what they see people doing and what they are doing.

And so, at the beginning, nobody seemed to care about all that, but then eventually got into a situation of some people started transcribe some of the Indian films into a literature, local language literature. And that caused a lot of problems because it uses the word love. The character would say to another character, of course male and female, "I love you." And that is wrong. That is absolutely wrong. Love has a very unusual status in Hausa language. You can only use it in the matrimonial sense. A husband can tell his wife, "I love you." And a wife can tell her husband, "I love you." But beside that, you cannot use the love in any other context. Because it will lead to misunderstanding.

So because of the link with the word love, and maybe sexuality, the public culture started arguing that the writers were simply giving a license for immoral behavior. That eventually led to the establishment of a censorship board to make sure that these things do not happen. And eventually we had the hisbah board, which is the moral police.

Kano State

Kano State

Let’s go back to history a little. Tell us about the Hausa and how things have unfolded in the north of Nigeria.

There have always been a lot of contentious issues about the origin. Who originates whom? Where do people come from? And I think in 2017 we have gone beyond all that. Nobody is interested in where somebody's coming from, because we don't have data. We don't have conclusive proof. It's all speculation. So we try to de-emphasize the issue of origins. But part of the origin legend has been distorted.

For instance, on of the things you find on the Internet is that there's a guy called Bayajidda, who established the Hausa state. That's wrong. When Bayajidda, if he ever existed at all, did arrive in the area that is now called Hausaland, he already met some people. He met a queen and a king. He met an empire. So he couldn't be a founder when there was already something. What was there to found? There were people. He married the queen, for crying out loud, because he killed a snake or something like that.

But he was the progenitor of the people who established political entities that became later on known as Hausaland. So that is the first myth that people have been given, that somebody from Baghdad, some kind of traveling warrior established Hausaland. He didn't.

I have read that. And when did this happen?

Something like the seventh or eighth century. The establishment of the city states was about 1080.

Photos by Banning Eyre.

Photos by Banning Eyre.

It is interesting the way the folks who are around now always want to erase the ones who were there before. We have the same thing in America, this idea that there were very few Indians before the colonizers arrived, whereas in fact, there were large civilizations.

And of course you have this idea that a white guy or an Arab came from the East. Everybody likes to believe that somebody from the East was their progenitor. Hey, I'm black. I am Negroid, so there's no way somebody from the East could have been my ancestor. O.K.? It's all a myth. And then that creates another myth, that Hausa is just a language. But it's a language that people speak. They have particular codes. They have dress, they have food, they have everything. So how could they just be a language? But because of the fact that the Hausa language has moved into so many areas, and it has absorbed words and vocabularies from other languages, people tend to see it as a construct. But it is not. Long before they met any other group of people, they had existence, they had kingdoms ruled by kings and queens and things like that.

So there are Hausa people who occupy what you could call northern Nigeria now. Then, in about 1250 or so, migration of Muslim clerics started from Mali, when the Malian Empire was expanding. So you had merchant clerics, as many as 50 in a group, and they were evangelists, converting people wherever they go, and establishing Islam. And gradually it all filtered down to the Hausa people, who accepted Islam in a very quiet manner, because it just was like something that they could accept. But even then, there was a sort of clash Before the clerics came, there were certain religious rituals that were based on, if you like, worshiping spirits.

Ancestors.

Yes. You should see a place in Kano called Dala Hill. That is where they had a small sort of temple where they worshiped the spirits. But the ruling house in Kano did not like that. Not because they were Muslims themselves, because they were not Muslims, but because they felt that power was probably being divided between the priests and the rulers. So there was always a battle between the two.

It's the classic church-state struggle.

Exactly. So when Islam came, it provided a credible alternative to that religion, and so the rulers in Kano accepted Islam very quickly. And that gave them a stronger basis to fight those that were not following Islam, particularly those who are following the traditional, ritual religion. Those Hausa who refused to become Muslims, who refused to accept Islam, retained their traditional beliefs, and they are called Maguzawa.

Maguzawa.

That's right. That's what they are called. They refused to become Muslims, and right from that 14th century up to now, we have a lot of Maguzawa and actually, one of them, a young girl, was a rapper. She's a fantastic rapper. Hassan will get you more details.

Kano from the air

Kano from the air

O.K., that is excellent. When we get to the 20th century, and the British come, and they adopt a more hands-off attitude towards the North than the South.

That's right. The reason they had that attitude is that the North already had an organized structure, in religion, scholarship, leadership. Because remember, right from 1000 A.D., up to the coming of the British in 1900 or so, they had almost 900 years of scholarship. From all our historical accounts, such sophisticated structures did not exist down south. So the British decided to prevent Christian missionaries from coming up to the north, because if they come up to the north to evangelize, the northerners will resist, and the British don't want revolution and fights. They are trying to exploit whatever they could. And they couldn't be bothered to set up an army just simply to get rid of all these fights and such between Christians and Muslims.

So they did not try to convert northerners to Christianity. That's important.

Absolutely. In fact the colonial conquerors of northern Nigeria were not a military force in the beginning. They were a commercial force. They needed cotton and there is a lot of cotton here. They needed rubber. They needed leather. This was an advanced market where they could get all these raw materials and take them up to Britain and into production. So they didn’t want to rock the boat.

You know, when the British came to the north, they found over 23,000 people attending schools. These were Islamic schools, Koranic schools. We had professors in Islamic theology and things like that. But nobody could write A-B-C-D. Because nobody knows. Then in 1910 the British established Western schools so they could get local clerks that they could work with.

In the south, missionaries were able to establish schools in the early 19th century. So before you know it, you have people going to the university and getting degrees, whereas in the north, you don't even have a person who has been to high school until 1910. And even then people didn't like it. That school was just to educate a small force of people that would allow them to communicate and do business. They were trying to create an Anglicized elite, not to educate everybody.

That's right. It was not meant to be a mass-educating thing. But you see, what they wanted to do, was if they educated the elites, if they educated people from the ruling houses, then those people from the ruling houses will now serve as a springboard for mass education.

People didn't like it, you say.

No. I remember vividly, when you put on your uniform and go on to school, kids who don't go to school would be following you, and singing a song: "When we go to heaven, there are those who will go to hell, and those who will go to hell are those who are going to school." It's just as simple as that. Simply because you go to white man’s school and you learn white man's education, you are going to hell.

Boko Haram.

Ironically enough, the word Boko meant "false” or “fake." Boko Haram doesn't mean education is prohibited. It just means that this education, which is false, is haram. It’s is prohibited. It’s fake. The real education is Islamic education. The idea of boko being haram is nothing new. It has been there for a long time.

Kano's grand mosque

Kano's grand mosque

So what was it like for you as a young person going to a Western school?

Luckily for me, my father was educated. So because I got inspiration from my father, I didn't care what other people were saying. If it was good enough for my father, it was good enough for me. I was even the librarian, surrounded by books. And ironically, those kids who were singing the songs are all old now, and we are the ones helping them, giving the money. They will come to us and say come, "I don't know how to feed my family today. I don't have money." But at the time, there was no psychological effect on me. Thanks to James Brown. Because I was listening to him all the time.

Brother James. The savior.

Yeah, really. I was listening to him all the time on the radio.

Let's talk about Hausa tradition, especially music and drama. Start with music.

Well, the Hausa traditional music is acoustic music, of course, with no guitars, no piano, no trumpets. Well, they have their local trumpet, algaita. But at the moment, there is a massive decline in Hausa traditional music, is because of the perception of the musician in Hausa society.

There is a paper by a guy called M. G. Smith. Check him out on the Internet, and he will tell you the division of Hausa society, that there is a first-class, which includes all the Emirs. There is a middle class, which includes big farmers, merchants and things like that, and then there is a low class, which includes musicians. Another reason why musicians are in that low class, is that musicians in Hausa society are seen as marukan, meaning beggars or mendicants. So your prestige in the society is always low. The vast majority of Hausa traditional musicians sing for well-paying clients, sometimes notorious and infamous people. Nowadays, when the people die, there are no replacements. The younger musicians don't want to do the same thing.

Professor Adamu, consulting in his office

But wasn't that always true, even in the past? What changed so that young people now don't want to follow that route?

I think there was a reawakening triggered by the Iranian revolution in 1979. That sent shockwaves throughout the Islamic world, so it led to some kind of assertion of a new identity reaffirming Islamicity. Suddenly people woke up and said, "It doesn't really make sense for me to buy an album of a musician who is just simply praising another person. If you have to praise someone, praise God." So then the old musicians themselves started granting interviews where they said they would not support their children taking after them. They want their children to go to school.

I have always found this ironic. This is an older musician that everybody likes. Everybody wants him. Everybody buys records and albums and songs. And yet, when his son says wants to marry your daughter, you say, “Oh no, there's no way I could allow that." And this drama occurs over and over and over again.

Right through nanaye and hip-hop and all these styles of music we have today?

Exactly.

What about the presentation of traditional music? What was it? One singer and a drum or a lute or violin?

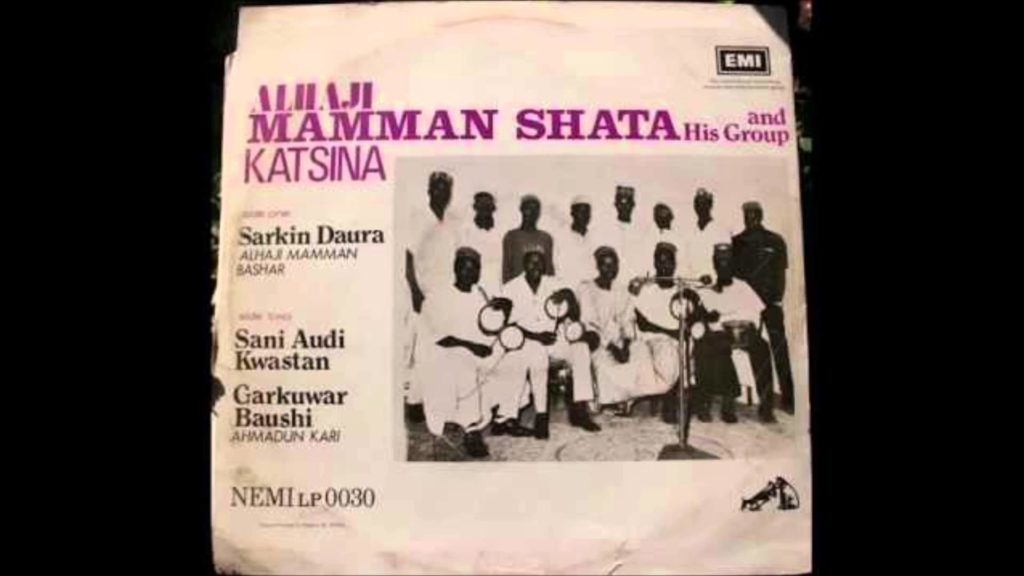

Basically, they have two types of formation. There is a kind where there is only the lead singer, who sits and just sings, and he has a chorus of about 12 people, and drums. He doesn't play any instrument. Maman Shata was one.

Yes, everyone mentions Shata. Tell us about him.

Shata was the most famous of all, with thousands and thousands of songs. "Sania Aliu Dendo," "Dan Kwairu." I mean there are a whole bunch of them. And then you have another kind of group where the lead singer plays an instrument, the kukuma. It's like a fiddle. Before the disco came along, they were in clubs doing this thing. And then they had a few drummers and the gurumi, another plucked string instrument played with a plectrum. And then there is kontigi, another stringed instrument.

Is there anyone in Kano who plays this kind of music?

Of course there is. Nasiru Garba Supa plays kukuma brilliantly. He has just released an album which I executive produced.

Nasiru Garba Supa playing the kukuma and singing.

O.K., let’s get the background on the film industry. I understand it starts with live drama performances.

In the emir's palace, there was a long drama tradition. People in the palace dramatized events in front of the emir as a way of telling him what is going on. It's like you can't come to the emir and say, "You! You know what's happening in your place? There is a problem." You can't do that. So what they do is, in the night they stage a drama, and it is through the drama that they communicate to him things that are happening, that are good, that are bad. And then he takes notice.

So right in the emir's palace there has always been this encouragement of drama tradition, and then young people in the schools were also doing drama, and then the clubs started being formed outside. This place, this building, is occupied by two of us. We are paying the rent. But the guy upstairs started also writing for drama clubs. And eventually, when the video camera became available, then they started transferring their scripts into the video thing, and that's how the whole thing started.

I know the early films were influenced by Indian films. How did Hausa people here in Kano start seeing those films?

Well, the initial Indian films that came were distributed by the Arabs, Lebanese Arab merchants. They were screening American and British and Italian films to the British officers. The locals were sneaking in once in a while to the cinema to see that. But after independence in 1960, the Lebanese decided to introduce Indian films in the local theaters. They screened the film called Genghis Khan. Initially, they tried to show films from the Arab world. People didn't like that.

Like Egyptian films?

Egyptian films, Lebanese films. I think those films at the time were too intellectual. They were message films, and they were just boring. But then the Indian films came along with the spectacular song and dance routines. That caught people's imagination. They liked what they saw on the screen. Indian men dressed like Hausa men with a long flowing dresses. The Indian woman had their sari, the wrap which is similar to what we have. They are shy. They have a lot of bangles in their hands. So there was an instant connect.

Now compare that to an Arnold Schwarzenegger film. There is just simply no connection. They don't see any way they can understand it, except for maybe some of the younger elements who are much more Westernized. But in the'60s, the whole focus is on cultural resonance. And the Indian films provide that perfect cultural resonance.

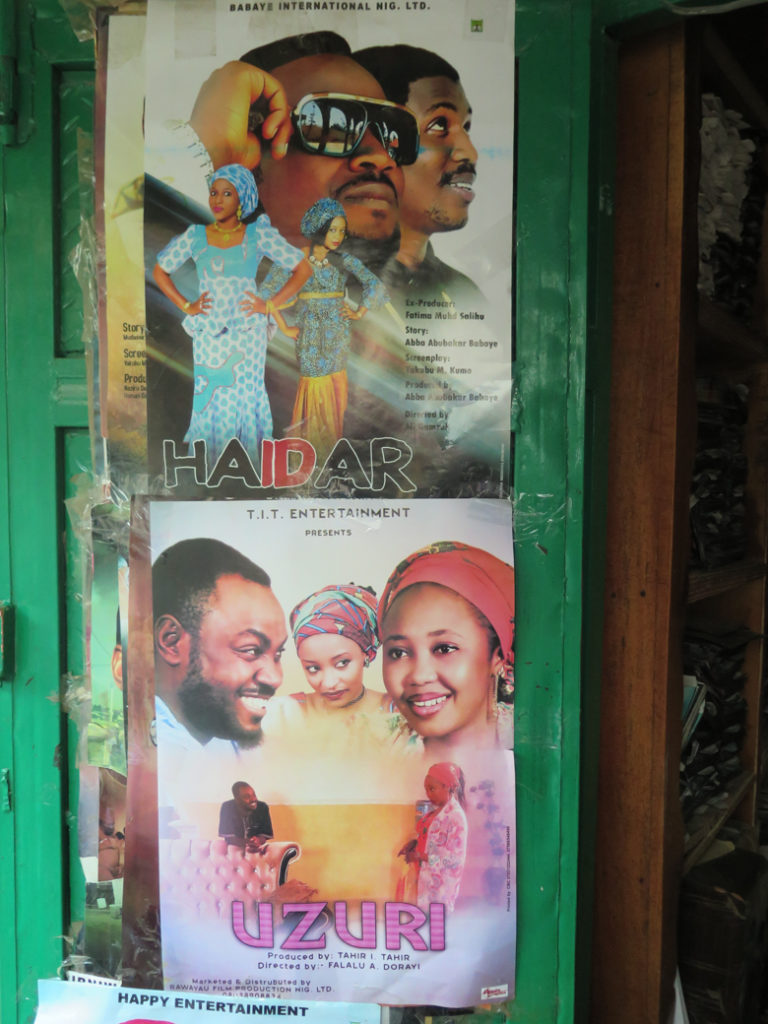

Kano film posters

Is part of that resonance also the tension between romantic story lines, but also restrictions on whether men and women can touch, dance, kiss, whatever?

Yeah, people don't touch each other. They don't kiss. They don't do anything. And the women in Indian films are shy, demure, you know, they flash their eyes. They don't talk back. That typical, macho, patriarchal image of a woman was reflected in the Bollywood films. And then the television stations started showing them as late-night movies, and that ingrained them in the consciousness of younger people. Because the act of going to a cinema was seen as immoral, men and women mix and all that. But when the Lebanese started leasing out Indian films to TV stations so they could show them on television, it becomes very easy now for people to see the films at home.

And I understand that that made women the majority of the audience. They couldn't go to the movies theater, but they could sit home and watch.

That's right. And the stories are all about emotion, love triangles. He loves one person, and another girl loves him. He doesn't know what to do. He’s conflicted. You get a lot of song and dance. And then eventually, they sort themselves out.

So that was it, up to the point when Amitabh Bachchan became the Indian film hero. He created the conception of angry young man. His films were more or less like American gangster films. A lot of shooting. A lot of spectacular stunts and stuff like that. And he had always this frowning face, looking stern, like a real dude.

And Amitabh became the instant model for Hausa films. So that is why there are films now following the Amitabh model. You know, I have over 120 Indian films that were more or less translated into our language, remade as Hausa films. Then as the Indian films evolved into what I call metrosexuality, the Hausa films also moved along and became metrosexual. That's what this thing is all about, imperialism from below. Media counter flows, and the emergence of Hausa metrosexual video culture—with the chest bare, groomed. Gucci, Bulgari. That kind of thing. I don't know. I've got my little belly and I love it. So they got all these pecs and … what do they call it?

Six pack?

Yes. Six pack. That's metrosexual. You want to show your six pack.

I haven't seen a lot of that around Kano.

Well if you do that, you will be arrested by the hisbah police. Even the haircut. You know the footballers now have some crazy punk haircut and things like that. Well, if the hisbah police see any young men with that haircut, they will take them to a local hair salon and scrape it off. Your hair has to be normal.

Professor Adamu and Banning (photo by Musty)

So what does the Hausa man who wants to be metrosexual do? He has to leave, right?

You might. But then you can hang out places where you know you can't get arrested, like in Sabon Gari. That is a settler zone for people who are not necessarily Muslim. Not from this area. When the British conquered northern Nigeria, they had to import people from southern Nigeria who were educated. But the Emir of Kano said, "I don't want non-Muslims to come inside the city wall." If you notice, there is a city wall. It is crumbling now, but there was a city wall at that time that encircled the entire city, and there were about seven gates that were locked at night. So the British created an encampment, outside the city wall for these guys. And the Emir said, "I don't care what happens there. This is not my territory.”

But now, the metropolis has grown up, but that area continued to grow up too, and to attract people from other parts of Nigeria and Africa. Sabon Gari or “new town.” That's where the action is. You want alcohol? That's where you get it. You want girls? That's where you get it. You want boys? That's where you get them. So people from the city sometimes sneak out go there and engage in the pleasures of Sabon Gari, and then come back.

Sabon Gari has always been a place where you can let your hair down. The hisbah police used to go there and conduct raids once in a while. They would seize alcohol, smash the bottles and things like that. So in the morning, you get a lot of drunken rats, mice and cockroaches running around drunk all over.

Films/CDs on sale

When did Kannywood, the Hausa film industry proper, first start?

It starts about 1980, '81 or so, and it started with a camera. The drama clubs didn't have access to technology. But someone went on pilgrimage to Mecca and came back with a camera. Then the drama club started borrowing the camera, or hiring the camera, to record some of their activities. But then, the technology opened up. More cameras started being imported, and people are buying them. So they now started moving their productions from just the stage to the screen.

So they started to dismantle the drama clubs, and everybody creates his own film production company. "Oh, I'm XYZ Production Company," and he's executive producer, producer, writer, choreographer, cameraman, everything. That's how they started. But eventually, they started forming real companies with a corporate structure, and this went on for the whole of the '80s. Actually, up to 1999, almost 20 years. That was the golden age.

But in October 1999, a company down here released a trailer for a film that kick-started the new Kannywood. That film was called Sangaya. It was brilliantly choreographed. Nice catchy songs. Nobody actually remembers the story. But the focus was on the choreography, the singing and so on. Up to that point, the singing and dancing was very tame. But when they did this in a very excellently choreographed way, it showed the world, yes, it can be done.

Sha’aibu Lilisko was one of the persons who was showing people how to do the dancing, and then he was preparing the film. So from 1999, 2000, all the way up to 2007: singing, dancing. I have to be more Indian than Indian. That was the mentality of the culture then.

And the music in those films was called nanaye.

Yes. Nanaye is a music that is made exclusively to be played in a film. No other context. Just a film. That's the evolution. But it didn't become a word, a living word, until after Sangaya. Before that, we didn't have any name for the music. But after the popularity of Sangaya, a producer called it nanaye, and it became a label for any music that has been composed exclusively for the film industry.

Why did they pick up that word? What was its origin?

Because that is the way the girls sing in a playground. Little girls. That is their chorus. So anything that is girlish, that is focused on singing and dancing in a chorus is called nanaye. It's actually derogatory, because it's not seen as an art form. Nanaye is a word that is very common in Hausa language, but it is always associated with female, children's entertainment. It's gender focused. It's all about the female, all the love songs center on the female. So nanaye becomes an apt description of that kind of music.

Most of the nanaye singers we have met are men. But I assume that there are a lot of female nanaye singers.

There have to be. There have to be male and female. Call and response. A male and a female. Nothing says the two of them are related. They just meet in the studio. They read the song, and then they record it, and then they part and they are given their money by the producer.

Maryam Sangandali, nanaye singer

I understand that nowadays, nanaye musicians make music for the market, not only for films.

Yes, the term nanaye has come to be applied to any song, whether made for film or not, in which a male and a female sing. So long as it has two voices, male and female, then it becomes a nanaye. And they hate it.

Who hates it?

The musicians. Because they think it's derogatory. They think it's restricting themselves to a film. And that is why I said up to 2007. 2007 there was a crackdown on the film industry. And it affected the nanaye singers, and they could not continue singing at all. There was a censorship ban. Then they realized that it was the film that was banned, but not the singing. So I can now continue singing without the film. They started creating their own new nanaye, which I call “post nanaye”—songs that have been composed, but not for any particular film. But up to 2007, if you produced a song and took it to the market, the first thing the marketer would ask is, "Which film is this?"

One singer told us that what they didn't like about being in the films is that they're kind of lost. An actor is miming their song.

That's right. They’re in the background. They are hidden. But since 2007, this post nanaye, they now can be seen. They make music videos, which are not films, but which feature them.

Ahmad M. Sadiq in the studio

We watched the producer Ahmad M. Sadiq make a song. Very quickly. It took no time at all.

That's what they do. It’s very spontaneous. They don't write the lyrics. In fact, some of them are very proud of the fact that they don't write any lyrics. They just go there and improvise into the mic in the word start flowing. And that is why they cannot repeat the same thing on stage, because they can't. These guys will tell you they have 3,000 songs.

Yes. Aboubacar Sani told us he’s made 4,000.

In fact there was a guy who said he had 30,000 songs. Now AC/DC is a group that I really love, and I know that the total number of albums that AC/DC made right from the start all away up to the one they kicked out recently, are not more than 20 or 30. And what about the Rolling Stones? These are guys whose hair is grayer than yours. And yet, yet, you can count the songs. They're not all that many. But here, they have 3,000 songs, because of that spontaneity that they talk about. They just go there and say, "Give me a tune." He sings, then she sings, and right away, you've got a hit tune, a slick, well-produced song. Then they go with the CD and to give it to the DJs, and the music starts, and then they just mime. And that's what they call live performance.

One of the other problems with producing the music live is that most of the vocals and the songs have been processed using Auto-Tune. It gives them that warbling, shimmering sound, and you can't easily do that live either. O.K., Let's switch to Hausa technopop. You say it started in 2003. Tell us about it.

Hausa technopop is a musical form that uses synthesizers in a much more structured r&b beat, using more disco-like beat. It is all generated by a synthesizer. Whereas in nanaye, the beat is to follow the male and female voices. The music follows the lyrics. But in technopop, separate them. So you have the music standing on its own, with its own line, and then the musician simply lays the track. And there's not much variation. So that's why I call it technopop. Synthesizer. Beat oriented. Independent. House oriented. Disco oriented. And the subject matter may or may not be about love, but mainly it's not about love.

Billy O is the guy who popularized that form of musical delivery. And he meandered into rap. Because inside his performances of technopop, he introduced rap. So Billy O is seen as the first Hausa rapper. But he was not the first person to release a rap CD. The first person to release a rap CD was Abdoulaye Imayti. He released the first rap CD, but it was Billy O who popularized the concept of rap music. Abdoulaye Imayti cut it on a CD, the first-ever rap CD in Kano.

Billy O taking a break from work at Dala FM

Around when?

Around 2008 I would say.

O.K., but just before that, there was this crackdown in 2007. What was that about?

2007 was when one of the filmmakers, Adam Zango, decided to release a music video called “Bahaushiya,” That’s the “Hausa Girl.” And there was a lot of dancing, and then the navel was shown, and Adam Zango was arrested. He was locked up in jail for three months. But he was released before the three months were over, and when he was released, he ran away from Kano. And then he released a song in which he abused the governor of Kano for incarcerating him. And that's when the rapper Hassan Mohamad and his colleague released a counter-song called “Bingo.” “Bingo” is a common name for a dog, especially a black dog. So it's like Led Zeppelin's "Black Dog." And so there was this war between Adam Zango and Hassan and his colleagues.

So 2007 actually marked the emergence of rap. Because when Hassan and his colleague did "Bingo," then other people started coming in and other defending the government for attacking other people. Then we said, "Look, rap is about expressing your own opinion. It is not about abusing somebody. We don't have these East Coast-West Coast wars. It doesn't make sense. If you want to rap about schools and education and life, or about money, about economics, go right ahead. But don't diss anybody, unless they did something to you.”

Adam Zango

From what I understand, when you look at the bigger Nigerian scene, there wasn't a whole lot of hip-hop and rap then. I have heard rappers in Lagos say that the real hip-hop started here in the North.

There is no connection between what we are doing up north, and what they are doing down south. Nobody bothered to create that connection. There are some rappers from the north who moved on to Lagos and establish themselves because the studios were available there. In fact the person who produced Abdullahi Mighty’s album left here because of Shariah and all that. He was a Christian. And he moved to Lagos. So you may be right. I don't know that much about the development of rap and hip-hop. But I can tell you 2Face and these artists now, we don't consider them rappers. Because rap is made up of three components. There is the beat. There is the flow. And there is the message. These three things are necessary for rap, even in New York. The beat has to be a rap beat. The flow has to be consistent, and then the message has to be about a social issue. This is what these kids are focusing on. And now you have girls, young girls who are moving it around. We have about three of them. So we have girls who are now moving into rap, Muslim girls who produce rap. And heavy rap.

So let's talk about the social environment in which this is happening. I know that artists have a hard time doing concerts because they can get closed down by the religious police, the hisbah. But at the same time, it feels like hip-hop is in the process of gaining more mainstram acceptance.

I wouldn't say it's in the process of getting accepted. I would still say that there are a lot of people who don't accept it up north, here in Kano, because they always associated, which is ironic, with American influences. The typical thing is, you are trying to imitate Americans. Why would you do that? Americans are bad. Because the rap that we do here is gangster rap. Tupac, Biggy Small kind of rap so people don't see that as good. So how do they spread it? WhatsAp, Bluetooth, they just keep spreading around among themselves. And that is why they are true artists. Because are not doing it to make money.

Hausa hip-hop graffiti at Arewa 24 television

You respect them, and I get the feeling they also respect you. You have a very unusual relationship with these artists.

I am the only academician today in rap. The other academicians do not think it is worthwhile studying. They only focus attention on nanaye, and even then, it is only because I did a lot of work on nanaye. And then I felt that I had reached a certain point where I'm not going to really go further. Then rap started emerging, and fortunately, I like rap. I lived in San Francisco, U.C. Berkeley as a Fullbrighter. And I've seen rap around, and I thought this is cool. Right now we have a little boy called Lil Ameer, just 12 years old. He’s a rapper, and he’s doing a very good job. So for me, rap is a reflection of urban dynamism here in Kano.

And we discovered that there is a relationship between the level of education and the preference and music. The less educated a person is, the more traditional music they like, and the more nanaye they like. The more educated a person is, the more hip-hop he likes. Because hip-hop is much more transglobal.

Who are some of your favorite Hausa hip-hop artists?

Oh, many of them. Mic Flamer. Dr Pure. Lil Ameer. And then there's a guy who's unusual, IQ. He sings only in English. Absolutely amazing. There are other rappers who try to sing in English, but the English is always coming out distorted, because they are trying to speak like Americans. They want to talk like Ice Cube or something like that. But the ones we prefer are the ones who sing only in Hausa language. They communicate their messages well.

Of course, they have limits on what they can say, in terms of sexuality, and probably also criticism of government and officials and things like that. One of the things I've noticed is that obviously compared to the musical world that we know, people here have to operate within some pretty strict guidelines in terms of what they can sing about and say.

That's right.

But I don't get the feeling from my limited conversation so far, people are not generally oppressed by that. They accept the fact that they have to create within these limitations. I don't feel like they are really rebelling against that.

No, because there is self-censorship, moral self-censorship. As an artist, I shouldn't do anything that would destroy my society. All Muslims have that instinctive, self-regulatory thing. I have to do something within Islam. I wouldn't do anything that would distort my image, or destroy religion, and things like that. So it's an inbuilt, self-censorship. And that is why they don't want to rebel. Nobody's going to come out and say, "We don't like the hisbah." O.K.? Because the hisbah is integral to the Koran. They are established by the Koran, not by any individual. If you rebel against hisbah, then you are rebelling against the Koran. And if you do that, then you are not in the religion. We don't have any problems, and we don't feel oppressed. Because that is how we are all wired. We are wired to accept it, and we have accepted it.

Dr. Pure (Saif Ibrahim) on air on Rahama Radio

Sean Barlow: What about artists who sing politics, questioning the balance of power, corruption, serious stuff, not about Islam, but about politics and corruption?

They do. Some of them. But everybody is scared. And when I say scared, I mean you can't just simply come up and say the government is doing bad and all that. You might be seen as subversive. But some do. One of the songs that I really loved is called "Change” by Lil Tea. That was released before the elections that brought the current government to power. And it was a really blistering attack on the previous government. Then after that government was toppled by election and a new government came in, he released a remix in which he said, "Now things are better."

Do you think this movement of hip-hop is going to eventually emerge more into the mainstream, with young people coming up who love it? Or will it always stay at the edges, underground?

It's going to stay underground. I don't think it's going to go beyond what it is now. The reason, first of all, for people to know you, you have to put on concerts and things like that. We don't have those kinds of opportunities here at all. So if you don't have a situation where you can go to a club or to a concert venue and we don't have concert venues, your craft is not going to survive.

That's number one. Number two. We don't have record companies that will record these people. We tried to do that. We got some money from someone who's a Nigerian Canadian. I invited about 10 hip-hop artists to come and recorded a demo so that we could release it so we can get some money. Then they started telling me their individual issues. They had problems, and therefore they need the money, and that was the end of that project.

Thirdly, public acceptance of hip-hop is not really at a level that we would've loved to see. People still see it as American, very, very Americanized, and that is not helped by the fact that some of the hip-hop musicians try to sing with a fake, exaggerated American accent, but when they do that, you can't even hear the words. Our rappers here who try to rap in English, you don't understand what they are saying. So people just tune out.

That's why a group like K-Arrows wrote a diss song where they dissed people who were singing in English. So we have these diss wars. "Why are you trying to speak a language that's not yours? Nobody even understands you’re saying. Hey, maybe you are not even Hausa, but you're claiming to be Hausa.” That's the worst thing you can tell to a person here, that you are not really Hausa, that you are Yoruba or something else. That is the ultimate insult. Because you are denying his identity.

Tagwayan Asali (Hausa hip-hop duo) and friends

So you don’t think rappers will go mainstream, but still you encourage them.

I encourage them. I like them. I listen to them, and when I criticize them, it is because I want global best practices in what they are doing. If I can listen to Shadia Mansur in Kano, why can't I listen to K-Boys in Cairo? I don't understand what she's saying. They don't understand what I'm saying, but there is a musical, universal message that connects us. That's very important.

And you know, that 2007 incident with Adam Zango was good for him. He’s bigger now than ever. And it was good for the creative industries in Kano. Really. The banning has forced other creativities to come out. And it elevated those that were unknown, like ALA. ALA was already a well-respected singer, but he couldn't find any outlet, because he was overshadowed by all the nanaye singers. When the nanaye singers stopped singing, that's when he shot up. So I think that was cool. I'm glad the kids seem to like what I was doing. I'm really happy. I will continue helping them out.

Sean: Can you give us a little primer for our listeners on Shariah law and how it came here, and how it affects this story?

Well, Shariah law has always been there since about the 13th century. It's not new. When you say Shariah law, you're talking about living according to the dictates of Islam. They've always been applying Shariah law since about 1250 when Islam came to northern Nigeria. But it was reactivated in 1999 by politicians. That's why a lot of people see it as political Islam. But even with, or without it, people live according to Shariah. Marriage was done according to Shariah. Divorce according to Shariah. All other forms of social interactivity according to Shariah. But it became political because now they're suddenly saying that they are going to use Shariah as a form of judgment in legal cases. And we launched it. As far as the creative industries were concerned, so long as you can conform to the traditional Muslim norms and values, then Shariah will have nothing to do with you.

You should speak with the head of hisbah. He’s liberal, really. Liberal. But now he is the enforcer who has to make sure that the society is clean. So, Shariah law is Shariah law. Creative industries are creative industries. There is no mix. There is no clash, except when the creative industries go out of their boundaries. That is when you have the clash. And so far, except for the cases like in 2007, they have been cleaning up their act.

Now if you want to do something really naughty, let your hair down and things like that, then you get out of the Shariah zone. You can go to Kaduna, about 250 km away. Or you can go to Lagos. And there, you can even appear naked and nobody cares. But so long as you're in Kano, there's a certain cleanness that has to be maintained. And we’re kind of comfortable with that.

Lil Ameer

Professor Adamu outside his office

For more photos of Kano, 2017, see our Kano Photo Essay.