Ever since the breakthrough of Tinariwen, the sight of Tuareg musicians swirling and bobbing their cheche-covered heads to the sound of electric guitars has become increasingly familiar. Mdou Moctar, whose debut album Anar has been released by Sahel Sounds, is one of the few Tuareg musicians who seem willing to experiment and push the boundaries of the genre. This boundary-pushing isn't only music: Mdou also plays a role in an African homage to Purple Rain-Akounak Teggdalit Taha Tazoughai, which translates as "Rain the Color of Red with a Little Blue In It," the first feature film ever made in the Tuareg language. Mirroring the famous '80s-era Prince vehicle, the film follows the loosely fictionalized story of a young guitarist struggling to make it against all odds in Agadez, Niger.

Moctar taught himself the guitar at a young age on a homemade instrument. Like many young Tuaregs, Mdou moved to Libya where he traveled and worked odd jobs. While there, he would meet many of the brilliant guitarists who had moved north during this period. Learning from them, he furthered his musical studies, and he returned home with a guitar and a dream. In 2008, as he traveled from the Azawagh Desert of Niger to Nigeria to record Anar, his songs were widely distributed via the cellphone file-sharing networks of the Sahara. Set apart by his adoption of Autotune and electronic effects, Mdou's music was embraced by a youthful generation.

"Tahoultine" sets the tone of the album, rough drum programming as a backdrop, for layers of syncopated handclaps, sub-bass lines, repetitive and hypnotic guitar flourishes, and finally swathes of Autotuned and filtered chants. This vocal style is influenced by Bollywood soundtracks popular in the Hausa pop music scene of regional powerhouse Nigeria.

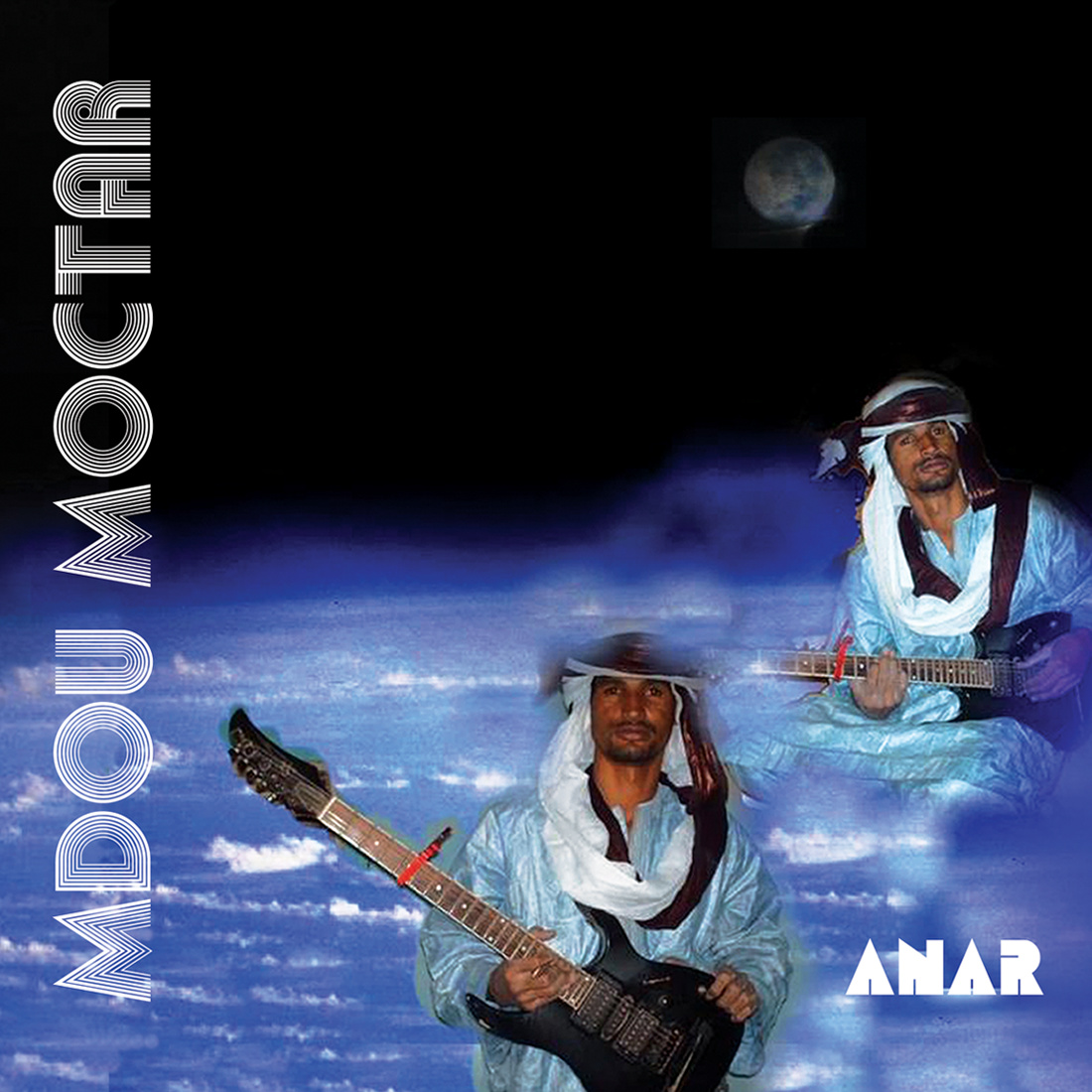

The contrast of texture in sound, the ethereal effect of the Auto-Tuned harmonies and the rumble sound of the guitars, leaves you stuck floating in a haze halfway between the dune and the moon, a space the album artwork invites you to imagine. The immediateness of the sound and roughness of the recording, a close listen to the glitches and incongruous sounds that litter the album add to the charm, making you feel almost as if you were invited into the recording studio. Anar can sometimes be a stranger and more jarring listen than other electric Tuareg recordings we have heard in recent years, but that isn't really a problem. Instead, it stands as a haunting, daring and danceable alternative. Even if you haven't mastered Tamashek or other Tuareg dialects, you'll soon be responding to the languorous calls of these songs.