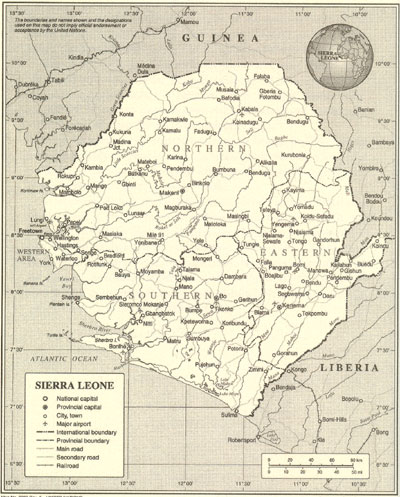

Music historian Gary Stewart and co-author John Amman gained a rare perspective on the Sierra Leonean Civil War (1991-2002) through a series of written letters they received from friends in Sierra Leone during the war. These letters form the backbone of Stewart and Amman’s new book, Black Man’s Grave. Stained with the blood of war, the stories in the letters also shed light on the incredible strength of the Sierra Leonean people. In this special conversation with Stewart and Amman, Afropop’s Wills Glasspiegel and Simon Rentner use Black Man’s Grave as a springboard to talk about life in Sierra Leone and its fascinating musical history. The following text was compiled from a lengthy conversation in John Amman’s Brooklyn apartment.

AFROPOP: Let’s start with a little background. How did you two meet? How did you come to write a book about the civil war in Sierra Leone?

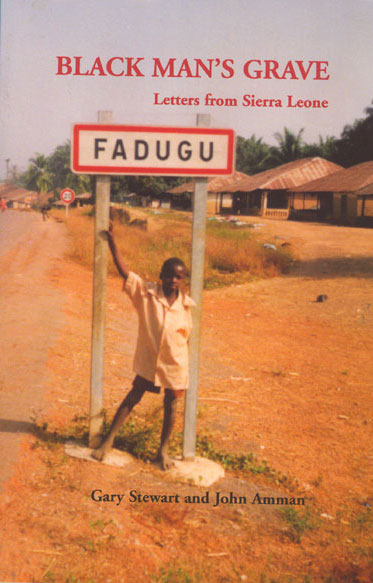

John Amman (J.A.): Gary and I were both Peace Corps volunteers in the same village of Fadugu. When I arrived in 1979, Gary was already somewhat of a celebrity. Then it turned out we were both from Michigan. When we came home to the States, we had many of the same friends writing to us (from Fadugu), and the letters became more and more dark in the years leading to the civil war.

AFROPOP: Could you read us one of the letters?

J.A.: (opening the book) “Please be informed that I have arrived in Freetown on June 29th from Conakry in Republic of Guinea. The junta/rebels attacked Fadugu township for a third time on March 9th of this year, leaving several people dead, destroying and burning houses (about 62 houses), and abducting men, women and children. The house in which I was staying was burnt including my personal belongings. The attack was launched in the early morning hours at about 6:15 AM by surprise while most of the people were still sleeping in their houses. I narrowly escaped while my house was attacked. It was a serious attack. About 150 well-armed rebels were reported to have attacked the township, two men were cruelly murdered on the spot, one had his intestines removed and the other had his head cut off, and they were left lying on the Makeni-Kabala motor highway. It was a very horrible, horrible thing. Some had their hands cut off and their bodies mutilated. In view of this dreadful event, I felt I was no longer safe to stay and moreover there was no home for me to reside in. Finally on March 13th I left together with my friend Musa, his wife and children for the Republic of Guinea. We traveled on foot through various bush paths until we succeeded in arriving in Guinea, where there was a large presence of Guinean military forces. We were given free passage until we reached Conakry, the capital city on April 19th. With the money you sent me in November, I was able to pay for my wife and children to travel to Freetown before the January invasion by rebels on Freetown. The balance was used for paying their tuition fees and other school charges... I must confess that all of them are doing well at school. And most important also was that all of them including their mother survived the January 6th invasion... I am happy to be with them once again after separating for a period of about eight months.”

AFROPOP: What was it like to receive that letter?

J.A.: The two things that struck me were the horrors of the events that this man had gone through, and yet the dignity he uses to describe them. He does not describe himself as being the victim. He does not describe himself as being in any way beaten down or defeated. Certainly he acknowledges the fact that the events that he witnessed were horrific events, but there is this resilience that comes through this letter. This is the letter that really prompted me to have the phone conversation with Gary about writing the book because there was a level at which I realized that Gary and I were getting an understanding of this war, and it's effect on people's lives, which CNN and The New York Times, and the BBC, and no one else was really getting.

AFROPOP: Now that we’ve heard one of the letters, could you give us a little more background about the war?

Gary Stewart (G.S.): The story of the war is basically the effects of a corrupt government. The government of Siaka Stevens came into power at a critical time in Sierra Leone's history (1967). It could have gone either way. They came to power through a democratic election. It was so democratic that they—the opposition—actually won the election. It was a critical time: You could either embrace democracy or you could embrace the "big man" corruption, and they chose corruption.

AFROPOP: Big Men?

J.A.: Big men are people of power, sort of big in every way: they're physically big; they're fat, so people would make comments on this, they're fat because they're eating money—they're eating the money of the people, so they're physically big; they're often overweight; they're well dressed; and they're riding around in Mitsubishis Pajeros (SUVS). One of the best political commentators that we had of the correspondents (who form the backbone of the book, Black Man’s Grave) was A.K. Bangura because he was the one that would make comments to me like, “You know why they're so fat” and I'd say, “Why?” and he'd say, “Because they're eating our money. If you eat the money you get fat.” It was a joke but it was also true. They can afford to be fat. They're eating all the money.

AFROPOP: How did this type of corruption relate to the war?

J.A.: The war took on a life of its own very quickly. The people that joined the rebel movement, including some of its leaders, saw the war as an opportunity to gain whatever they could gain. So the idea wasn't to go in and liberate anybody. It was to go in and take advantage of the fact that they had guns and the people in these villages didn't. Even the way in which the war was financed is an example of that—the rebels took over the diamond-mining district, forced people to mine diamonds for them. They would take the diamonds and they would take them into Liberia where they would be sold and the money from the sale of the diamonds would be used to buy weapons. It's probably more useful for people to look at the war as a series of criminal gangs that were out to take advantage.

G.S.: There were two tiers of people who would join the rebel movement. There was an intellectual tier. These were frustrated college students who had a good education and couldn't get a job anywhere unless they sucked up to the party in power, and many of them resented that. Then there was the bottom tier—the people with no education who couldn't get a job and were just scraping by and were eager to latch on to a big man and do his bidding to make a living.

AFROPOP: Could you tell us more about your friend who actually went through this process of being associated with a “big man”?

J.A.: He said it was extremely intoxicating because he had never had so much power in his entire life. He would go in to places and if he wanted to eat something he would take it; if he wanted alcohol he would take it; if he wanted women, he would take them as well; and he said that eventually in his case—I don't know what happened because he wouldn't tell me—but there was something that went on with him that demonstrated to him that he was becoming what he hated, and he walked away from it. When I met him he was just devoted to agriculture, to farming, and uplifting people, but there was something that went on, maybe some act of violence that he was involved in that seemed to haunt him. During the war, there was the sense that these young guys who never really had much respect, and suddenly they got it, you know suddenly they're going places, and people are forced to listen to them—I think to a certain extent that describes the initial rebel movement. The people that would've joined up, would've been people that were kind of drawn to that same sense of "This is an opportunity, I can make a mark, I can gain some status very quickly", and because of the nature–really the brutal nature of politics in Sierra Leone under the Stevens regime—this was the norm; this was how politics ran. Politics was a nasty, bloody business, so you're going to tie your horse to the guy who's the toughest and roughest and is going to give you the most opportunities personally.

AFROPOP: How did you understand the underlying cause of war? How can we understand why such atrocities were committed?

G.S.: It's almost inexplicable, unless you can explain it by seeing [the fighters] as criminal elements that are simply out to get their own share of the pot that they were deprived of from the government in power. Certainly, their actions did not in any way demonstrate that they cared about the people of Sierra Leone in general. For the rebels, there's a couple of theories or explanations for cutting off ordinary citizens' hands, and one was to prevent them from voting. The other was to prevent them from harvesting. It's reminiscent of King Leopold's Congo when people were forced to harvest rubber, and if they didn't meet their quota, overseers chopped off hands as an example for other people. So, I assume that the rebels thought they were making examples of these people and saying, "Look, you either cooperate or you lose a limb."

AFROPOP: How did you respond when you first heard about the war through the letters like the one you read to us from your friends in Sierra Leone?

G.S.: I don't know—you feel helpless in that situation. What can you do? You can try to send money to help people survive, but there's not a hell of a lot you can do.

AFROPOP: What about musicians? What was their role in the country at this time?

J.A.: It was the same with them as with the general population—people just wanted the whole thing to end. With the musicians that I met, they weren't siding with anybody. In the clubs that we'd go to, in the bars where musicians were playing music and were performing it, a lot of the themes were just about ending the war, just ending the conflict, you know, getting the peace. It wasn't, at least from what I was hearing, it wasn't so much about propping up the existing government or the rebel forces. It was just about ending this thing.

AFROPOP: How did politics affect music?

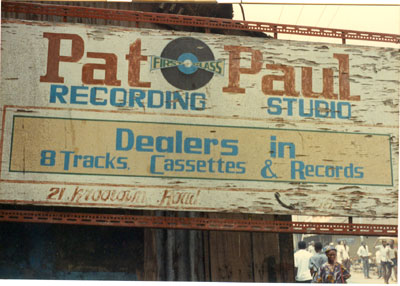

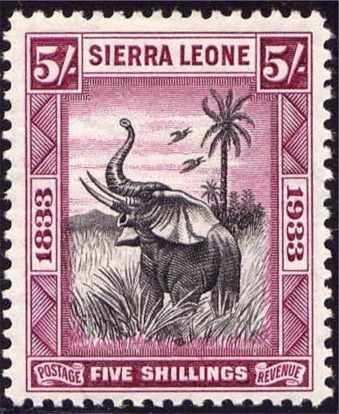

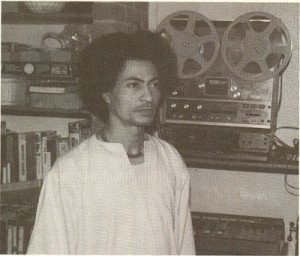

G.S.: A lot of the bands—probably all of the bands, actually—owe their existence to some big man back before the war. For example, the band Sabanoh 75 started out as Akpata Jazz, which was a band of the Sierra Leone People’s Party. So, in that sense, musicians did have allegiance simply because it was a big man financing them. Part of the problem in Freetown was that, as the economy deteriorated, there was less foreign exchange to import instruments. The musician, Abou White, explained to me a novel means of financing equipment purchases before the war: people bought old stamps, sold them in Japan and used the proceeds to buy goods. Sierra Leone postage stamps were valuable; he had plenty of them. You send them abroad and get a lot of money to buy the goods you want. I imagine people still do that; it was like selling antiques.

AFROPOP: Stamps for instruments.

G.S.: Isn't that funny? It's the craziest thing.

AFROPOP: I wonder why that is. Is it just because the stamps were valuable as a collector's item?

G.S.: Sierra Leone used to produce works of art—these beautiful, intricate postage stamps.

J.A.: I remember when I first went there, the stamps were beautiful.

G.S.: In the '60s, they had these really beautiful postage stamps that people valued.

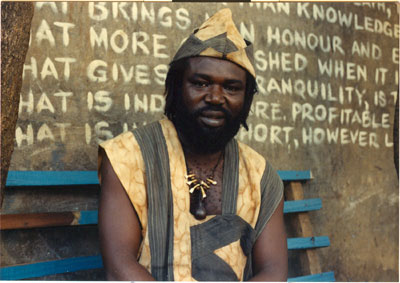

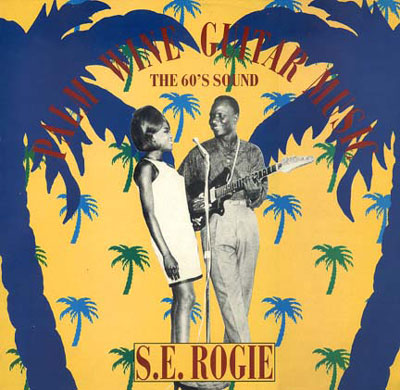

AFROPOP: As we learn more Sierra Leonean music, we keep hearing more about the sounds of palm wine guitar music. Please tell us about S.E. Rogie.

G.S.: When I lived in Freetown (in the 70s), I heard the music of S.E. Rogers, and his nickname was Rogie. Eventually when times got tough for him musically, he moved to the United States and he thought "Rogers" didn't sound African enough, so he picked up his nickname and began calling himself S.E. Rogie. He was a quintessential palm wine musician. He drank the wine and played the music and sang the stories of life in Sierra Leone. He was very good at it. His career went downhill in the '70s, and then I helped him put together some of his old songs into an album that we called "The '60s Sounds of S.E. Rogie." I sent some copies to DJs in the U.K. and they picked up on it and Rogie was invited to come over and do some performances and he signed a record deal over there. His career had a rebirth.

AFROPOP: And that's the recording that you can find now in stores?

G.S.: That's the record, but it's been re-titled now. It's now on CD from Cooking Vinyl and it's "The Palm Wine Sounds of S.E. Rogie."

AFROPOP: I love that album. You must have spent a lot of time with Mr. Rogie. What’s a story that you remember about him?

G.S.: Well one time Rogie had a scheme. Once he hit it big in the United Kingdom, he saved up some money and he sent me to Germany to buy used cars for him. And we shipped the used cars to Freetown to resell and used the Sierra Leone money to build a nice house out in the Wellington section of Freetown. But unfortunately, he never got to live in the house. His career went well, and then he began to have heart problems. Eventually, he died during the war and his body was returned to Freetown. They tried to take him up country for burial, but his hometown was occupied by the rebels. So they couldn't bury him in his hometown.

AFROPOP: Let's talk a little bit more about palm wine and we can get back to the war.

G.S.: John’s the palm wine expert. [Laughs] I never liked the stuff, but John is a connoisseur.

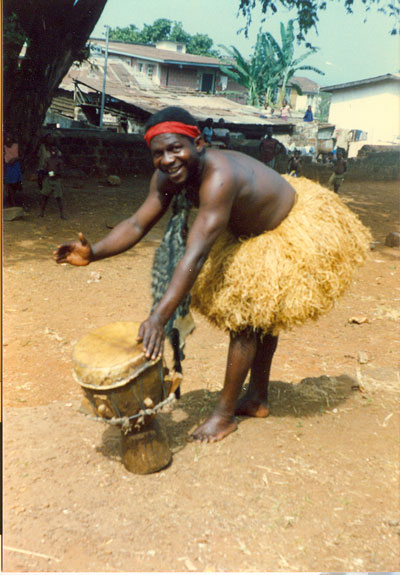

J.A.: I was forced to drink it. Fadugu is the center of a Limba chiefdom. And the Limba tribe is famous in Africa for tapping palm wine. When I say tapping, you literally tap the stuff in much the same way that maple syrup is tapped, only it comes out quicker. So they would climb to the top of a palm tree, and there was supposed to be a real art and science to this because not everybody could do it well, and you'd traditionally have a large gourd you'd call a boli and it would fill up. It was supposed to be best in the morning. It was almost effervescent… and different trees would have slightly different tastes. There was a lot of combined socialization and drinking that went on with this stuff. So there was the art of getting the palm wine and having the connections with the farmers to bring you the wine, and then there was the whole thing of sitting around and generally sharing the same cup. So it would go from person to person and you would drink the wine and it was an acquired taste. It had sort of a sour aftertaste. The most foreboding part of it was the fact that when the gourd is sitting there filling up, certain types of flies would lay their eggs there, so there would be the maggots, the larvae, which had to be pushed to the side; they would float to the top, but once you got through all of that it wasn't bad.

G.S.: Just to relate this to music, the whole palm wine experience is a communal experience of people getting together and, often, someone would pull out a guitar or a homemade lute and begin to sing and tell stories, and that's where the palm wine guitar music developed all along the West African Coast, not just in Sierra Leone, but Ghana, Nigeria…

J.A.: The catch phrase was to keep company, and this was a highly valued attribute that Sierra Leoneans would have for Peace Corps volunteers in general, the people remarked about this with Gary when I came, Gary was keeping company with people, the idea was that you would just sit down and you would just hang out. The palm wine in that village was a very important part of that, and like Gary said, there was always storytellers, and there was always a lot of spontaneous music in Sierra Leone, where people would just get up and sing, or just dance

G.S.: Rogie had a really good quote that's pretty succinct. He says, "Palm wine music is like folk music or blues. People sing heart-to-heart songs about what they feel. They drink a little to feel happy, and what they drink is palm wine."

AFROPOP: That's a good quote. That's beautiful. Gary, you've studied so many different strains of music, what’s different about Sierra Leone?

G.S.: I think what's distinctive about Sierra Leonean music is that it's indistinct because there are so many outside influences on the music. Sierra Leone, especially Freetown, which is where the pop music mostly originated, is an amalgamation of enormously diverse peoples. They're descendants of repatriated slaves who came from all over Africa, so all of their traditions grew up in this music—and then you have all of the influences from abroad, especially Western pop and dance band music. Probably most importantly in Sierra Leone pop music is Congolese music. So you see all of these different things going on Sierra Leone music. It's so different than the homogenous music of, say, Mali, or Burkina Faso, or places like that, just because the population is so diverse.

AFROPOP: Has there ever been a campaign or cultural movement to try and say, "This is Sierra Leone's sound?" Like, there's samba in Brazil or cumbia in Colombia or joropa in Venezuela or jazz in America. Is there anything like that?

G.S.: No. In fact, I think most of the musicians pride themselves on being able to play many different things. There was some great reggae music that came out of Sierra Leone. You also had a guy like Ali Ganda in the early '60s who did calypso, The Heartbeats did James Brown stuff, and so many of the bands emulated the Congolese musicians.

AFROPOP: Gary, could you tell us more about the Congolese influence?'

G.S.: Well, there was a band that was really influential called Rico Jazz. It was this traveling band of Congolese musicians and they encamped in Freetown for a couple of years and made a lot of records and performed all over the country doing dances and such. They were very influential. Then the great Congolese guitarist, Dr. Nico, and his band African Fiesta came and played several concerts in Sierra Leone. They were hugely popular and the Sierra Leonean bands loved the guitar styles, and they all tried to pick them up.

AFROPOP: This was in '69?

G.S.: This was in the '60s and '70s. Jimmy Cliff was also immensely popular in Sierra Leone and lots of Sierra Leonean bands picked up reggae and did some great reggae songs. Then, eventually, the music of Bob Marley and Toots and Maytals came in.

AFROPOP: John, what was your experience of reggae in Sierra Leone?

J.A.: Really my first introduction to reggae music was in Sierra Leone. I was in Sierra Leone when Bob Marley died, and the effect of his death was felt equally there as it was felt anyplace else in the world. In Sierra Leone, there's a tradition of when somebody dies, when a family member dies you have a seven day ceremony after the death, and then you have a forty day ceremony, and people were literally having seven and forty day ceremonies after the date of his death, they were literally in mourning, because they felt the effect that his music had on their lives.

G.S.: The same can be said of Franco from the then-Zaire, now Congo.

AFROPOP: Was the reggae philosophy of African Zionism attractive to West Africans?

G.S.: I think it's the feel of the music. I think that's the big appeal and that's why every culture picks it up.

J.A.: It's true, it's the feel of the music. I don't think that African Zionism was as relevant in Africa. In Sierra Leone, people weren't talking about that. If they were talking about Bob Marley's lyrics, what people would talk about with me was this general notion of world brotherhood, the way his music would juxtapose the third world with the superpowers. But the discussion about a back to Africa movement wasn't so much relevant.

G.S.: The message of reggae really resonated in Sierra Leone. You're talking about people who threw off colonialism only to have their own black brothers put, basically, a black colonialism back on top of them. The message that Bob Marley and some of the other reggae singers were saying really resonated with people who were on the bottom. Especially, those suffering under the yoke of mental slavery. It was kind of a black power—throw off the colonial mentality and take control.

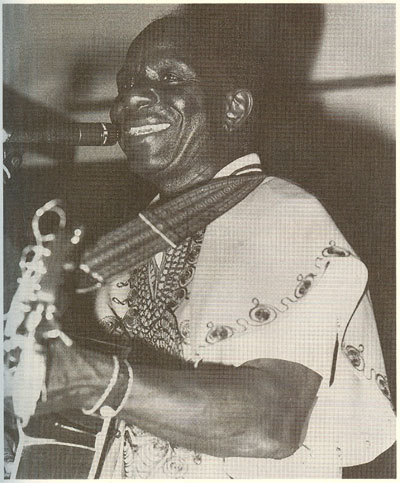

AFROPOP: Could you focus a little on the '70s bands that you referenced for us, especially Geraldo Pino and The Heartbeats?

G.S.: The Heartbeats picked up on the soul craze that came out of America. They specialized in doing covers of James Brown. Then they threw in some of their own indigenous creations, and they were a big hit. Fela Kuti was blown away by The Heartbeats when they came to Nigeria because of their professionalism. They were rehearsed, the group was tight, they had the first-rate equipment—stuff that he'd never seen at that point. He just thought to himself, "Wow, I've got to get my act together." Also the Super Combo Kings (are worth mentioning)–they’re a band from the mid '60s that was very popular. People were really taken by the guitarist, Freddy Green, who was apparently somewhat mentally unstable but was a fantastic guitarist. Sabanoh 75 were extremely popular, as well. There was a kind of competition between Super Combo, Sabanoh 75 and Afro-Nationals.

AFROPOP: Please tell us more about the music.

G.S.: One thing about Sierra Leone music that I think is remarkable is that it wasn't exactly "message" music; it was fun music. It was bands congratulating themselves and naming the members of the band and saying how cool they were, and how much better they were than the other bands in town. It was funny stories, like Afro-Nationals talking about how the lead singer's mother-in-law is fine, and how he's admiring her more than his own wife, and how he sends his wife off into the bush so he can hang out with the mother-in-law. So before the war, the music was really party music. It was very joyful, and I think the music has definitely changed. After the war, people are a lot more serious. They're talking about more substantive things than people going out and having an affair or going out and getting drunk or partying. It's interesting because I just saw a video of some friends that they sent us from the village that I used to live in. I thought it was remarkable how serious the faces were. It was unlike the pictures that I used to see from Sierra Leone where the people were laughing and smiling. People just looked much more serious. Like they were still in shock, still recovering from the trauma.

J.A.: The song Corruption is, I think, what Gary's getting at. Because even though there's a lively beat, the message is pretty clear today: that ordinary Sierra Leoneans recognize the immensity of the problems of corruption, the role it played in the war, and how they have to deal with the problem. There's a whole campaign that was tied around that in Freetown, about corruption, and the music was being played often on the radio. The lyrics were like “Corruption Corruption, It's enough, we've just had enough.” Unfortunately, corruption is still there, but now the discussion is there, too. People are talking about this more openly. When I first went to Sierra Leone back in ‘79, if you would've had a song about corruption, it would have been banned or seen as a joke. But now it’s not funny.

G.S.: Another thing that just occurred to me is that part of the difference in the change in music is that, as part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions' work in trying to get the country reunited, they enlisted musicians to really talk about serious subjects as a way to try and heal the wounds of war and bring the country back together again. That's part of the difference.

AFROPOP: How does international aid function in Sierra Leone today?

G.S.: Many of the NGOs that are involved in rebuilding the country are bypassing the government channels and they're taking whatever it is—be it nails, corrugated roofing or cement—direct to the people to see that it really gets where it's destined.

J.A.: This is one of the reasons why the nonprofit that I helped found, Sierra Leone Village Partnerships (SLVP.org) works at a grassroots level—to bypass government and to go directly to communities. We don't feel comfortable dealing with the Sierra Leonean government. We don't quite trust it, so we'd rather work with community leaders and local chiefs where we know that when we send materials, they’re less likely to be sucked away someplace.

AFROPOP: One big question we now have for you is: Where exactly is Sierra Leone today?

G.S.: All over the world. [Laughs] Sierra Leoneans are everywhere. The abandonment of Sierra Leone happened long before the war. People in economic distress try to get out of that and go to a better place. Sierra Leoneans did just like Mexicans do or people from other African countries or even European countries. If you can't make it one place, you try to get to another place. Sierra Leoneans went to the U.K., they came to America, and they went to France, Eastern Europe—so there are refugees all over the world.

AFROPOP: Does Sierra Leone exist in D.C. and Maryland? Would you say the country is there, living? Or are those people Americans?

J.A.: Sierra Leoneans in exile is what they are. I lived in DC in the early nineties. I would get into a cab and I would meet a Sierra Leonean, and it would be some guy, and he's a cab driver, but in Sierra Leone he was like a senior teacher at the school, he might have been somebody who worked in a ministry job. There is a brain drain in Sierra Leone itself. The people that left say in the eighties were often educated and had connections, and they could leave. Sadly it was often times the kind of people you wanted to stay in that country.

G.S.: Now the diaspora is a huge source of income for Sierra Leone—people sending money back to Sierra Leone from America. And also among the Sierra Leoneans that you'd find in the Diaspora, you'll not find one who says they're never going to go home again. They're all going to go back home one day and live in Sierra Leone. Just about everybody would say that. Whether they'll make it or not, I don't know.

J.A.: There was an interesting comment that was made when we were working on the book. A [Sierra Leonean] was talking to us about that they were grateful that they had won the visa lottery and they got out of the country and their children were in a safe place and the two boys weren't child soldiers or anything like that. But in the same breath, they all desperately missed living in Fadugu and how safe it was prior to the war, that wherever her kids went in Fadugu, someone was watching them. There was this whole community that supported everybody and they all took care of each other. There is a great loneliness now living in the United States.

G.S.: The thing about living in the tropics is that everybody's outside. People are always outside and they see each other and they sit out on the verandas and wave to each other in the streets. So when they come to a society like we have in the United States or in the U.K., everybody's in their own house and they go out and get in their car and go somewhere—everybody's isolated. It's very unsettling to people who come from Sierra Leone.

J.A.: But when we went to Sierra Leone, it was at first unsettling because people are just in your life all of the time, commenting on it.

G.S.: Yeah, sitting on your veranda. They'll just come up and just hang out on your veranda. Even if you're not there or if you're in the house, they'll just come and hang out on the veranda and wave to their friends.

J.A.: And they'll talk about you. "Oh, John, I saw you walking…” They know what your business is.

G.S.: And it's fun to talk about it. [Everybody laughs]

AFROPOP: Speaking of sitting on the veranda, let’s get go enjoy this beautiful day. Thank you both for your stories and for you incredible book, Black Man’s Grave.