Carmen McCain is an assistant professor of English at Westmont College. Her research focus is on Hausa-language literature, film and popular culture. Hausa is a language spoken by over 50 million people across West Africa. Most native speakers are in northern Nigeria and Niger, but there are also Hausa-speaking communities in Benin, Togo, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, the Sudan and elsewhere. It is the most widely spoken language in Africa, after Arabic and Swahili. Carmen was a driving force behind our program "Hip Deep in Northern Nigeria." She introduced us to Professor Abdallah Adamu and other invaluable sources and helpers. Before the Afropop team left for Nigeria in January 2017, Banning Eyre interviewed Carmen. Here’s an edited version of their conversation, focusing on the Kannywood film industry and the scandals that have challenged its progress in the 21st century. (Featured image shows Carmen McCain with the Hausa comedians Baba Ari and Gatari.)

Banning Eyre: Thanks for all the help, Carmen, and for speaking with me. To start, you partially grew up in Nigeria, didn’t you?

Carmen McCain: I moved to Nigeria as a child with my family in 1988, when my dad began teaching at a university in Port Harcourt. We were in Port Harcourt for three years, and then moved to Jos, in Plateau State, in what we call the “middle belt.” I learned a little bit of Hausa as a teenager, simple greetings and market Hausa. So later, when I was in my Ph.D. program in what was then called the Department of African Languages and Literature at they University of Wisconsin, and I was required to become proficient in a Nigerian language, I went back to Hausa. At first I was planning to study Nigerian literature in English, but in 2005 when I went to Sokoto, Nigeria, in the northwest to study Hausa, my teacher had me reading Hausa literature and watching Hausa movies to learn the language. And I was blindsided.

I had grown up in Nigeria and had spent more time there right after college on a Fulbright, spending time with English-language writers who met with the Association of Nigerian Authors in Jos. But I had never realized that there was a flourishing tradition of Hausa literature and film in the North. So, I fell in love. In 2006, I went to Kano, the commercial capital of Nigeria, and an ancient stop on major trans-Saharan trade and pilgrimage routes, and this is where I first began to meet Hausa writers, filmmakers, and musicians. I returned in 2008 and spent five and a half more years in northern Nigeria, doing research and writing.

In this show, we’re going to tell a story about film and music in the time of Shariah law. But maybe you can give us a little history. What do we need to know about the Nigerian north in order to appreciate this story?

People have been writing in the region we known as Nigeria since the 11th century. The Kanem Borno Empire, in what is now Borno State, had contact with Islam from the ninth or 10th century, and Kano had contact with Islam at latest by the 14th century. So from this time there is a literary tradition that is both oral and written. You have popular song and also songs that were written down by Islamic scholars, such as the 16th century poet Dan Marina from Katsina, whose songs are apparently still being sung today. In the early 19th century, the Islamic reformer Usman Dan Fodiyo and his family, including four of his daughters, wrote and translated poetry between Arabic, Fulfulde and Hausa. Verse was written in Hausa often as a tool for teaching conquered people about Islam, and the verse structure helped people memorize and sing this poetry. So, there was a fluid overlap between the oral and written tradition. There also seems to have been a little bit of conflict between popular forms of music associated with the non-Islamic spirit possession traditions and Islam. Nana Asma’u, the daughter of Usman Dan Fodiyo, wrote a poem called “Prayer for Rain,” actually meant to be sung. Here’s part of it:

Let us return to the Path of the Sunna and be redeemed.

Respecting each other, banding together as colleagues.

Do not go where there is immoral drumming and chatter

For men and women mix together on these occasions.

The beating of drums in jihad is permissible

And so is drumming when communal work is being done

And the beating of drums in the heat of battle

And to announce the return home.

It is advisable to beat drums when traveling

Otherwise people stray and get lost.

But do not allow drumming at weddings to accompany wild dancing.

Let us live in the remembrance of the Hereafter….”

(Translated by Jean Boyd and Beverly Mack, from their volume The Collected Works of Nana Asma'u.)

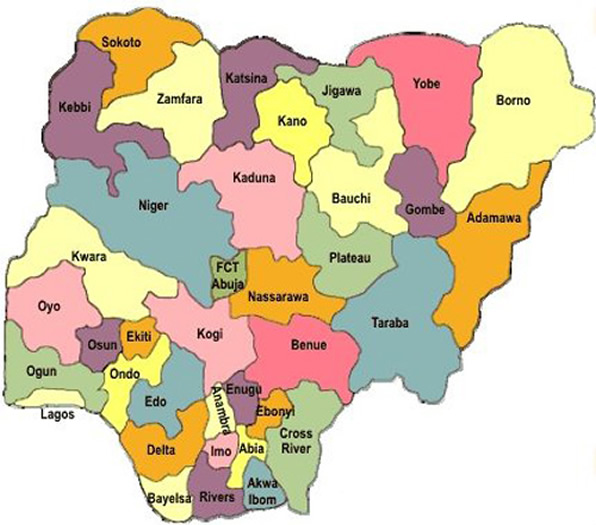

From 1809, after the jihad that started in 1804, northwestern Nigeria was ruled by the Sokoto Caliphate, established after Usman D’an Fodiyo’s jihad. This was the power structure in place when the British defeated Kano and Sokoto in 1903. The British then set up a system of indirect rule, ruling through the pre-existing emirates until Nigeria gained its independence from the British in 1960. So the nation of Nigeria that was founded by the British has always included within it multiple nations. In the 1970s, some northern Nigerians began pushing for the establishment of Shariah law in the north. The justice system introduced by the British was seen as a “Christian” system and is known for its corruption and delay. The call for Shariah was seen as a way to bring back a kind of justice that had existed in some parts of the north from the time of the Fodiyo jihad in 1804.

In 1999, the military government handed over to what we call the Third Republic, because it was the third period of democratic rule in Nigeria since independence. Shortly afterwards, the governor of Zamfara State, the northwestern state, next to Sokoto State, declared that the new constitution made it legal for the state to institute Shariah law. Nigeria’s constitution learned from the American constitution in giving states rights. So that is how individual states in northern Nigeria began declaring Shariah law. Theoretically, it was only supposed to be applicable to Muslims, not Christians, in those states, and those convicted under Shariah law do have the ability to appeal to the federal courts. There was kind of a populist demand for Shariah that began to sweep across northern Nigeria at that time. And the governor of Kano State at the time Rabi’u Musa Kwankwaso instituted it in Kano, many think somewhat reluctantly, in the year 2000.

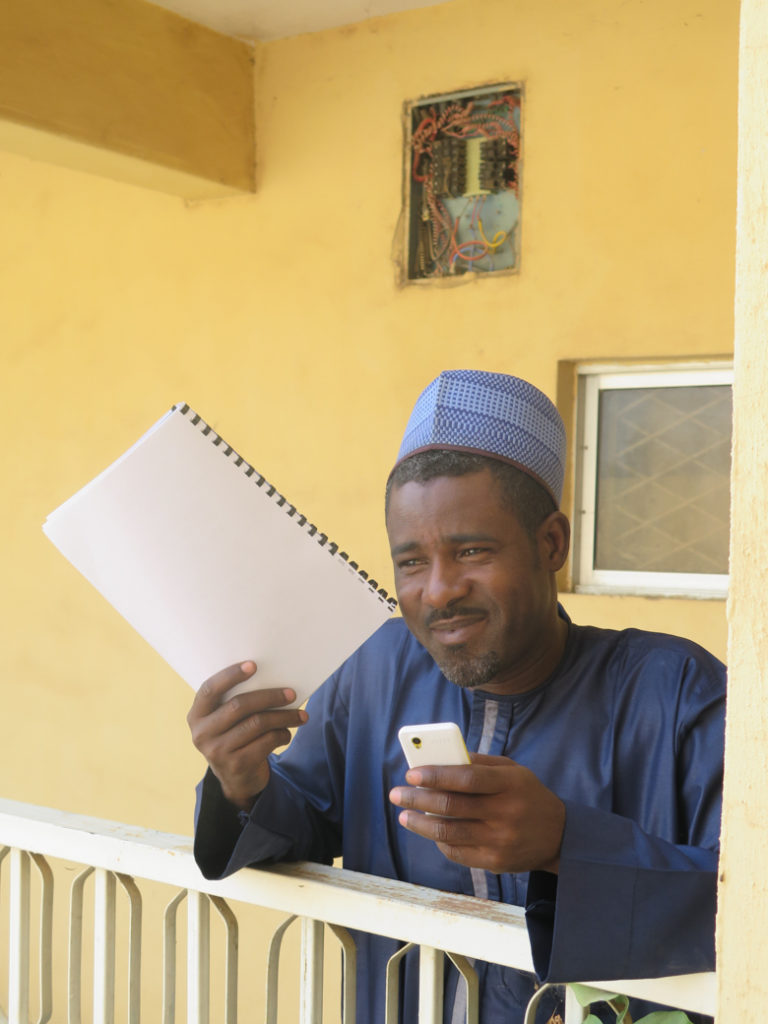

Actor Mustafa "Musty," Afropop's number-one research assistant and inside man in Kano

Actor Mustafa "Musty," Afropop's number-one research assistant and inside man in Kano

How did the local film industry start in this region?

The local film industry grew up out of drama clubs. Some of these drama clubs had been around from the 1940s. In the 1980s about the same time other people in southern Nigeria, Ghana, and elsewhere were beginning to experiment with filming low-budget productions on VHS, Hausa artists were experimenting with capturing drama on VHS as well. These drama clubs also produced shows for state television, and they were so popular that some marketers sold copies of the TV performances dubbed on VHS in the market. During the 1980s, the then-military dictator Ibrahim Babangida had yielded to World Bank demands for structural adjustment programs, which killed Nigeria’s economy. State television was having a hard time paying artists for their work, so the Tumbin Giwa drama club decided to make their film and sell it directly in the market. So, the first successful independent commercial film production was Turmin Danya in 1990. That was followed by other popular films like Gimbiya Fatima, the first part of which was made in 1992, and films like In da So da Kauna, based on Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino’s bestselling novel by the same name.

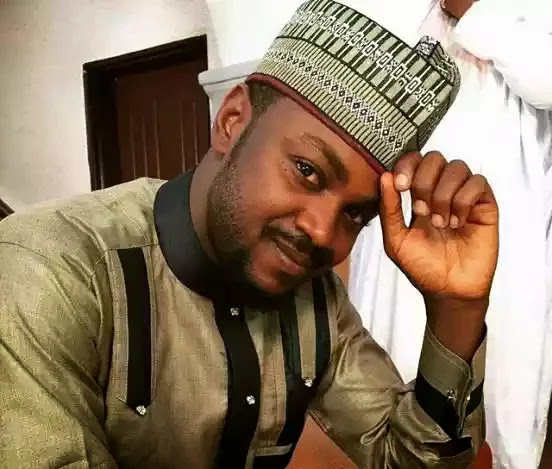

Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino (Eyre 2017)

Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino (Eyre 2017)

What were these films like, and what made them so popular? Along the way, maybe you can tell us the origin of the term Kannywood.

The films, like their southern cousins often called Nollywood, were popular because they showed recognizable places and customs and were made in the language everyone spoke. They were also quite popular among women, because cinemas, which had been around in northern Nigeria from the 1930s, were not seen as places where respectable women could go, but video players that could be hooked up to televisions at home gave women access to films. Before Hausa films became popular, Indian films had been very popular both in cinemas and on “home video,” so filmmakers themselves, especially the second generation of filmmakers in the 1990s, had grown up with Indian films constantly playing at home.

The films from the beginning have also had a lot of overlap with the popular literature being written in northern Nigeria from the 1980s on. Novelists were sometimes also actors, directors, and scriptwriters, and adaptations of novels were often made for film. Some of the more popular ones were In da So da Kauna, based on a novel about star-crossed lovers, a rich girl and a poor boy. This novel sold over 200,000 copies and was read out loud over the radio, so it also made for a very popular film. Other popular early films were adapted from Balaraba Ramat’s Sin Is A Puppy That Follows You Home, Bala Anas Babinlata’s Naira da Kwabo, down to more recent films based on the novels of Jamila Umar Tanko, Nazir Adam Salih, Fauziyya D. Sulaiman and others.

The term Kannywood was coined by Shehu Sanusi Daneji, a publisher of a Hausa entertainment magazine, Tauraruwa, the Stars. He was a fan of Hollywood, and in 1999 he created a gossip column in this magazine called “Kanywood.” This name was modeled after Hollywood. So, the name caught on from there. Interestingly, some Nigerian filmmakers think that Kannywood was modeled after the name Nollywood, which was bestowed on the southern Nigerian film industry by the New York Times in 2002, but the Hausa film industry had been called Kannywood for three years before this name came out.

Carmen McCain and Professor Abdalla Uba Adamu

Carmen McCain and Professor Abdalla Uba Adamu

Glad you cleared that up! Tell us about the relationship between film and music in Kannywood.

In early films like In da So da Kauna, there was singing, a teenage boy and girl, star-crossed lovers, singing love poems back and forth to each other. But in the late 1990s, Hausa filmmakers began to more closely imitate Indian film music. Films would usually have at least three or four songs and they sounded very similar to Indian music too, with the call and refrain between men and high-pitched women’s voices. As time went on, Hausa music began to have a distinctive sound, but it is still recognizably influenced by Indian film music. This Indian-inspired film music is called nanaye. In fact, this music completely changed the popular music scene in northern Nigeria. If you hear Hausa music on a radio now, it is most likely nanaye.

Tell us a little about the cities of Kano and Jos. We will visit Kano, so that will be our focus. But it would be great to hear about both cities and what distinguishes them.

Kano is an ancient trade city on the trans-Saharan trade route; the foundations of the current city walls were laid as early as the 11th century. It continues to be an important market city, and has the largest economy in the north. The development of the film industry, and the Hausa publishing industry, in Kano was particularly important because of Kano’s powerful market. It is a cosmopolitan city with a history that goes back at least 1,000 years. People were writing scholarship from the 14th century in Kano, and it was a stopover on the Hajj route from Timbuktu, so you have a long history of scholarship, writing and trade.

Jos is a city in the middle belt and, unlike majority Muslim Kano, is majority Christian. Jos is located on the Bauchi plateau in Nigeria, which because of its rocky terrain was never conquered by the Fulani jihadists in the early 1800s. However, when the British came along, they did place it under an emirate, and this has been a source of resentment for a long time. Many of the people who lived in Plateau converted to Christianity in part as resistance to this older Hausa-Fulani colonizing force. The Plateau is around 4,000 feet in elevation and has a temperate climate, so the British colonialists built rest homes and resorts in the city. Under colonialism, tin mining became a major part of the Jos economy, and this led to miners coming from all over the country, so Jos also became quite a cosmopolitan city with people from all over Nigeria. If you look now at many of the major musicians, actors and filmmakers in Nigeria, both in the southern Nollywood and the northern Kannywood, many of them have some kind of association with Jos.

The singer 2Face Idibia, the rapper M.I. and his brother Jesse Jagz, the duo P-Square, Ice Prince, Jeremiah Gyang, known all over Nigeria—they all grew up in Jos. The hot new filmmakers Kenneth Gyang, Abba Makama, Africa Ukoh, and others also grew up in Jos. In Kannywood, we have stars like Ali Nuhu, who went to the University of Jos, Abbas Sadiq and Zainab Idris, popular actress Nafisa Abdullahi and others who grew up in Jos. So, it was a meeting place between the north and south and a very creative place. Hausa filmmakers began making films in Jos in the early 1990s and it is one of the hubs of the Hausa film industry. Unfortunately, the ethnic and religious crises that began in force after 2001 made it more difficult to film in Jos. Actors did not want to come in from the outside because they were afraid of danger from Christian militias. But there is still a sizeable industry in Jos, and there are quite a few films made at the Jos Museum where there are replicas of the Kano emir’s palace and other architectural wonders.

The most recent conflict between the Jos-based industry and the Kano-based industry came in August 2016, when the Jos-based musician Classiq had Kannywood actress Rahama Sadau act in the music video of his song, “I Love You.” He raps in English and Hausa, code-switching between the two. In the music video, there is some mild handholding and hugging. Rahama was banned by the filmmaking body MOPPAN (Motion Pictures Practitioners of Nigeria) for acting with these displays of physical affection. The music and the video is exactly the sort of thing that is coming out of Jos, Christian and Muslim artists working together to produce sophisticated edgy productions. But the touching between a man and woman is seen as too “Western” and immodest by Kano standards. Only a few months ago, a film village, basically a studio sound stage, that the Buhari government promised to build in Kano was canceled because conservative clerics preached that the film village would corrupt vulnerable women and children. [Editor’s note: Many people we interviewed in Kano said this happened because clerics were thrown by the word “village.” They did not understand the nature of the project. Some hope and expect it will be revived.] The tension was high again between the filmmakers and certain gatekeepers, and MOPPAN warned all of its stakeholders to be careful. Rahama’s appearance in the video seemed to Kannywood leadership in Kano to be deliberate rebellion against this political purpose. But from my perspective, at least, as a Jos girl, she was just engaging with Jos-based media.

Talk about the introduction of Shariah law in the north and how it has affected film and music.

I mentioned a little of this previously. The call for Shariah was introduced by politicians as an issue to help them get the votes and then became a populist movement—I sometimes compare it to the evangelical movement in the U.S. and the idea that society would be a better place if we elect Christian politicians or impose laws based on Christian convictions. People believed that justice would be swifter and that society would be a better place if Shariah law was in place.

In 1999, the Zamfara State governor Sani Yerima—who later became notorious for marrying a 13- or 14-year old girl—instituted Shariah law in Zamfara State, and from that time there was a populist wave across the north with Shariah by popular demand. In 2000, Kano instituted Shariah law, and in December 2000, state government banned the “shooting, production, distribution and showing” of films in Kano state, saying that film “constitutes an incalculable damage and nuisance on the sacred teachings of the Shariah legal system” (Media Rights Agenda n.d.).

By this point there were thousands of people making films, so the leaders of the various film guilds and the umbrella association of MOPPAN wrote to the government and told them that if they could provide them with an alternate source of livelihood, they would leave their profession, but otherwise they needed to come to some kind of compromise. The compromise turned out to be a review board, which the filmmakers themselves proposed as a way to make sure they could keep making films but with some oversight that satisfied their harshest critics. This was the birth of the Kano State Censorship Board.

When I first started my research in Kano in 2006, I visited the board, and there was a group of people watching films to censor them. This would include the filmmaker, and other members of society. The censors board seemed rather mild when I observed them. In fact, I remember I watched a film with them, and there was this rather dramatic scene of a man smothering a woman with a pillow, and the censors were in good spirits and didn’t say anything about it. I was also given a sheet of prohibitions. Some of them are the same as the rules by the national film and video censors board, which prohibits any material that could cause interethnic tensions by defaming religion or culture, some are more Shariah specific:

Film producers should prevent:

1) Close dancing between a woman and a man.

2) A girl appearing in tight trousers or a short skirt in a film

3) Leaving hair uncovered [for a woman], unless the story indicates

4) Putting on tight clothes that reveals the figure of a woman

5) Insulting or lack of respect for elders

6) Insulting or demeaning another religion or culture

7) Using children for scenes that are not appropriate for them

8) Using rituals or magic in films in inappropriate ways

9) Showing nudity, sex or vulgar actions

10) Ridiculing a specific person or a people or going against Islamic law

In 2003, Ibrahim Shekarau won an election on the promise to more fully institute Shariah law in Kano, as the previous governor Rabi’u Musa Kwankwaso was seen as being rather half-hearted about it. Shekarau won and formalized the hisbah, a kind of Shariah vigilante group, and an organization called A Daidaita Sahu, the Societal Reorientation Directorate. This directorate erected signs around Kano with verses from the Koran and also published didactic novellas in Hausa to replace what was seen as the more worldly novels being read by girls. In fact, in one case, a girls’ school called the girls to an assembly, the staff went through and found several hundred popular novels. The directorate sponsored a book burning with the fodder from these girls’ books and replaced the books with the didactic novels the directorate had sponsored.

In 2007, rumors went around that a polygamous lesbian wedding had taken place in an open-air theater where galas often took place. Galas were events where actors would mime to popular film music and attracted a lot of film fans. But with rumors about the lesbian wedding, the open-air theater was razed. From there, a scandal took place that rocked the industry. A private phone video taken by an actress' boyfriend while they were having sex was leaked and became a hot-selling commodity in Kano’s download market. Shocked conservatives called for a ban on the film industry, and the Kano State censors board shut down the industry for the good part of a year.

So, I returned to Kano in 2008, and the industry I had seen in 2006 had completely changed. In 2006, I would see filmmakers everywhere on the side of the road cheerfully dancing and miming to music from boom boxes for the films. Now, there were almost no films being made in Kano. Kano-based filmmakers had begun traveling out of state to make films and would come back to edit the films in Kano studios. But in order to sell the films, they had to access the Kano market, and to access the Kano market, they had to pass their films through the Kano State Censorship Board. If a film that had not passed through the board was found in Kano, it was labeled “cocaine,” and marketers and filmmakers could be arrested.

Three of the highest-profile cases happened because uncensored films were found in the market. The first was the arrest of the actor and musician Adam Zango, who had released a music video album Bahaushiya (Hausa Girl) in Lagos. It featured some dancing girls who briefly exposed their navals in some scenes, and the overall album depicted Hausa girls as materialistic and unfaithful. Adam Zango was arrested and imprisoned for two months—the ostensible reason being because he had not censored the album with the censorship board. But articles about his arrest also mentioned the offensiveness of the album and the shameful way it portrayed Hausa society.

Secondly, two of the most famous comedians, Rabilu Musa Dan Lasan known as Dan Ibro, and his colleague Lawal Kaura, were arrested. They were arrested ostensibly for being producers (they denied it) of a film that had not been censored. But it turned out to be a pirated music video album of greatest comedy hit songs. Rumor had it that the governor had it out for Dan Ibro because of a comedic song where he had mocked the kind of cloth that the governor wore. It became such a popular song that apparently children mocked the governor with the song when he went to events and it made it difficult for cloth merchants to sell that cloth. They were also imprisoned for two months

Finally, one of the most respected elders of the film industry, Hamisu Lamido Iyan-Tama, who had previously been awarded prizes from the Hausa film industry for his family-friendly films promoting Hausa culture, was arrested over a film, a Hausa take on West Side Story that had been sponsored by the U.S. embassy to promote peace in Nigeria. The claim was that the film had been found uncensored in a Kano market, even though Iyan-Tama, trying to reduce the headache of dealing with the board, had gone on the radio saying that the film was not for sale in Kano. He spent several years battling the board in court and three months in prison.

Eventually, this crisis petered out with a change in political power, and when the head censor, who had traveled around demonizing filmmakers, was caught in an alleged sex scandal of his own. However, there continue to be tensions between the censorship board and the leaders of the Kano-based industry who want to appease conservative critics, and edgier filmmakers and musicians, as we see in the case of Classiq and Rahama Sadau.

Adam Zango

Adam Zango

Well, we will soon see what the situation is like now in Kano. But what's your sense? Have things come back since 2011?

Yeah. I left shortly after Kwankwaso came in. Since then it's been almost seven years and there have been a lot of changes. When the new government came in, he actually put Dan Ibro on the censors board. He has since died, unfortunately. But there are people, filmmakers, who are now on the board, and who still have problems with the Hausa film industry. So the kind of crisis between gatekeepers and the filmmakers has not stopped. I mentioned that the Kano film village was not built by the government because of all these critiques of clerics and social critics, and the crisis where the actress was banned. Other actresses have been banned too. So there's often scapegoating of women for what people see as the corruption of the filmmaking industry. So these things are still going on.

Some of the crisis now is that there is so much piracy. It's hard for people to make money, because of all the pirates. So the first thing on people's minds is not necessarily the censorship board anymore, but actually the ability to continue the film industry in an age where there's so much satellite television. So there are stations like Africa Magic and Arewa 24 and other stations that have bought up a lot of copies of Hausa films. So now a lot of people watch things on television, kind of going back to the way it was formed in the 1980s out of television. It has kind of returned to television.

And so it is difficult for filmmakers to sell videos and make money anymore. Because as soon as they release a film, within a day or so, the pirates have it, and they sell far more than the producers and marketers selling legal copies. So I would say that, when I talk to people, that is the main concern. And that would be something interesting for you to explore.

We will certainly do that. Thank you!

Carmen McCain in Kano during Eid el Fitr, 2008

Carmen McCain in Kano during Eid el Fitr, 2008