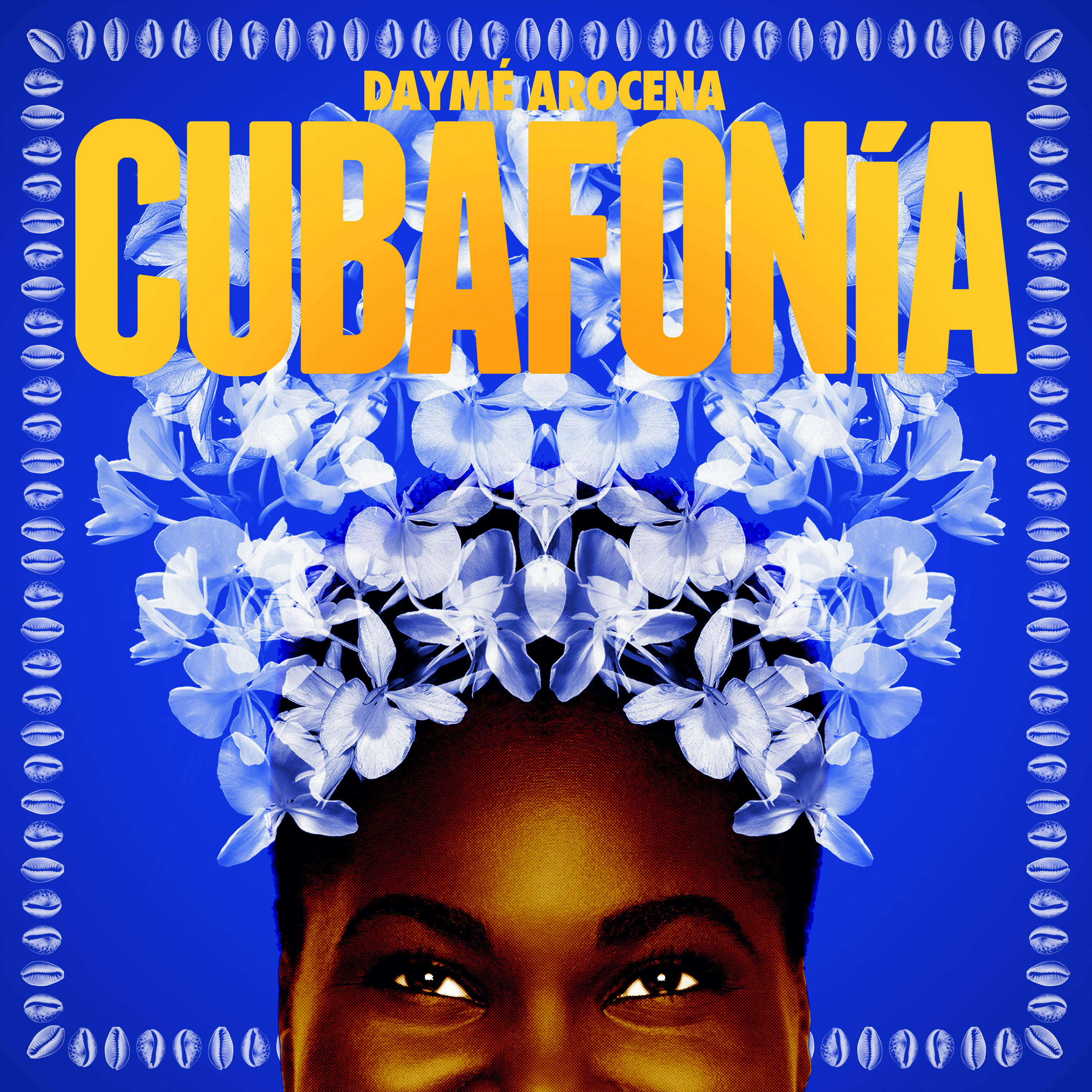

After two years of extensive and well-received international touring, Cuban rising star Daymé Arocena returns with her second album, Cubafonía. The record sees the 25-year old singer, composer, arranger, choir director and band leader as strong as ever, as she turns her focus towards the musical richness of her native island, exploring its vast rhythmic and melodic landscape through 11 ambitious compositions. Staff writer Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar spoke to Daymé by phone from her home in Havana, Cuba to learn more about her new album, her recent conversion to Santería and the beginnings of her international career. Cubafonía is out on March 10, 2017 on Brownswood Records.

This interview was conducted in Spanish. The original transcription can be found here.

Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar: Hi Daymé. Where you are now?

Daymé Arocena: Hi, I’m Daymé Arocena, and I’m speaking from Havana, Cuba.

So we know you have a new album out soon, after several other records with great success. How is Cubafonía a step in a new direction relative to what has come before?

What’s happening with Cubafonía is that it’s a record made up exclusively of my songs, written with the goal of in some way recreating the typical and traditional rhythms of Cuba. Because what happens is that people know mambo, people know chachachá, people know a lot of Cuban rhythms but don’t know that they’re Cuban. So with this record I’m trying to get the world to recognize Cuban music, and through my songs it forms an exploration of the rhythms and genres of Cuban music which are integral to the history of music on a global level and which, maybe because Cuba is a tiny island in the middle of the sea, people don’t always recognize as styles born in Cuba.

I’ve noticed your mastery of various musical styles at your concerts. Can you tell us about your musical background? How did you learn about and become proficient in all of these different Cuban styles?

Well, I’m an academic musician. I went to music school, I studied at the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory, where they teach us Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Strauss, Mahler and Wagner … but they also teach us the Cuban classics. And at some point we play the classic styles of popular Cuban music, though without giving them great recognition because the school is focused on classical music. But we understand them, we recognize them and we study them. I think that school was my first connection to traditional Cuban music styles. And after that, the street, and life in general, taught me how beautiful they are and how influential they are on the lives of every Cuban, musician or not. So that’s where it began, my complicity with the musical styles which I was born into. And then what happens? In the case of rumba … there are genres that we are more in contact with, because people play them in the street, hear them, feel them … but there are genres like changüí which are completely autochthonous and which are really from the end of the country, they can be found in Guantanamó and in far-away provinces. So it’s hard to follow those rhythms and I couldn’t encompass all of them in my record. I tried to put tango congo, old-school rumba, modern rumba, pilón, bolero, chachachá, mambo … but many styles are missing. I missed dengué, nangón, sucu-sucu … even the conga! You know, Cuba is a sage, it’s a mountain spring of music, I’d even dare say it’s a powerhouse. I’m willing to say that whoever really wants to be a musician needs to visit at least three countries in their life: Brazil, the United States and Cuba.

Have you traveled a lot throughout the island to collaborate with musicians, or have you mostly been based in Havana for your musical work?

That’s one of the things that I owe myself. I’ve traveled the world but I haven’t traveled much throughout my own country, my own land. It’s missing. I have the fortune to work with musicians in Havana from all of the provinces, who come and teach us things that we sometimes don’t know. Because given that Havana is the capital, well, everything happens here, the musicians from the countryside come to Havana, and we share and get together and learn. But I haven’t been able to make a trip across and throughout all of my country, only to study. It’s something that I owe myself, that I have to do. I can’t die without doing it.

As you’ve traveled around the world, touring through the United States and Europe, how have you seen your music or more generally your perspective on music and art evolve?

Well, with respect to my music, it evolves just as I evolve and just as my thoughts evolve. My music changes as my experiences change. It’s a reflection of my life, of the things that happen to me. I’m honest when I write music. I don’t sit at the piano and make up things that don’t exist. Everything that happens in my music is an answer to my life as a whole. In that way, my musical evolution is based on my human evolution.

How has your band evolved? I saw your concert in New York in early January. Not only was I impressed by your presence and your voice, but I also found your band’s communication remarkable. How did you meet your musicians, how long have you been playing together and how have you developed your sound as a band?

We’re all a family, a beautiful family of friends. A sincere family. It’s not about, “Hey, we love each other like family,” and then it’s all a lie. No, we’re a real family: we tell each other off, we console each other, we help each other, we give each other advice, we’re a team and we support each other. What happens with my band, is that this connection can be heard. When you’re playing with a band, which more than a band is your friends, and more than your friends is your family, you play with confidence. Because you know that, just by looking into the other’s eyes, you can understand what he’s going to do, how he’s going to play, what’s going to happen. And that didn’t come one day to the next, that’s a connection that we’ve been building bit by bit. We’ve known each other for years, and we’ve been playing together for less—maybe a year and a half, two years—but it’s been easy, because the feelings are mutual.

Are all of your musicians Cuban? Do they have musical backgrounds similar to yours?

Yes, they’re all young Cuban guys. Some are younger than me, others are older, but we’re all young and that’s the most important! [Laughs] Youth, what a divine treasure! And they’re all guys who have their own projects, their own concerns, their own musical goals. Each one of them has something to say to the world.

In terms of saying something to the world, do you have a general vision of what you’re trying to bring to the world through your music? Where does the motivation for your musical work come from?

I feel that I have a vision in life, which is to bring a message, through music, of strength, perseverance and humanism. You know, I’m a woman who has overcome many things, and my music has been the antidote that I’ve found to solve many problems. I think that music can heal the world and I want that to be my legacy in this life. Those who know say that I’ve lived many lives, other lives, and that’s why I’m an old soul. But in the life I have to live now, I want to show the world that music can be a remedy for so much hate, for so much suffering, for so much pain.

If I understand correctly, you practice the religion of Santería, which is expressed in various ways in your music. Can you tell us more about it and explain how it came to be a part of your life?

Santería came to my life through music. I fell in love with religious music, because it has so much to draw from and build upon. Religious music has an impressive rhythmic and melodic richness. Initially, I composed a lot of music for choirs, because that’s what I studied. I’m a choir director, I graduated with a degree in choral direction. I composed a lot—a lot—for choir. In that way my attention was drawn to the combination of classical music with Cuban religious music, and from there grew my love for all of the mysticism that was involved in interpreting and making religious music. That’s where it comes from, yes. After, I asked my grandmother, who is the only Santera in my home, whether I should be a Santera because at the time certain things were happening to me—personal things and spiritual things which I wanted to heal and remedy—and she asked the saints and they said yes. So, with all of the love in the world, my grandmother made me Ocha, made me Yemayá (who is my mother) and Obatalá (who is my father). I am the daughter of the sea and of peace. So they were crowned on my head and today I live with my saints in my home.

Was this recent?

This year will be my third year as a Santera. Yes, I’m not an old Santera, I’m just a little girl in the religion. However, my best friend has been Santera for 23 years, and we’re the same age. She was made Santera at two years old, I was made Santera at 22.

Thinking of your Cuban audience, how did your success outside of the country influence your domestic career?

In Cuba, I had a lot of obstacles to be a musician, to be the musician that I wanted to be. A lot of doors were closed to me. Others were opened, but many were closed, for reasons that are irrelevant … because I wasn’t up to the country’s beauty standards, because I walked barefoot, because I was making the music that I wanted to make. I wanted to play jazz with my own Cuban influences. And I was discriminated against in that sense many times. But this year is an interesting year, even if it just began, because this year, stemming from my international artistic reach and the success that I’ve had in these past years, you know, people have started to pay attention to what I’m doing and to recognize it. And today I’m getting solicited by people who didn’t value me in the least, people who crushed me, people who told me that I would never get anywhere if I continued in the direction that I was working in, people who told me, “If you want to triumph, stop signing the music that you’re signing, get on a diet and lose weight, put on some high heels, and go get a perm and some extensions.” You know? People who tried to change who I am … now they’re calling my home to congratulate me, to invite me to concerts, to recognize my work. So in the end, I think so much fighting bore its fruit, and now in Cuba people are bit by bit starting to better understand Daymé and what she projects as an artist.

I’m happy to hear it. In terms of that development over the past few years, can you tell us how you began to make these international connections, in particular with the Havana Cultura project?

That was a beautiful coincidence. I was called in for an open mic, because Havana Cultura was organizing an event with Cuban singers and with international DJs, and the DJs had the opportunity to listen to many signers and decide who they wanted to work with. So I showed up to the open mic, along with a lot of other people, sang the one song that I was allotted, and left. The act of singing one song meant that you would be chosen or not. I had the luck, to put it one way, that all 10 of the DJs chose to work with me. That was the start of it all, because they were 10 DJs from different countries. There was a Russian, a German, a Swiss, a Chilean, a South African, a Hungarian, an Englishman … I don’t remember but each guy was from a different country with its own culture and its own musical ideas. For Havana Cultura and for Brownswood, it was impressive that 10 people from ten different countries voted for me when they had the opportunity to choose other singers. It was such a big deal that they had to decide that only four of them could work with me because it would have been too many otherwise, they couldn’t make a record of Cuban singers with only one signer. And that’s how it started, the consequence of all of those 10 DJs wanted to work with me, and then they invited me to London for the album launch and then they proposed that I record a session for the first time, a session album, which is the album that’s called The Havana Cultura Sessions: Daymé Arocena. And that’s where this whole infinite journey began. When I say infinite it’s because it’s a spiritual journey, one of personal rejoicing. It’s a divine trip.

That’s a great story. The world is lucky that things worked out that way and that so many have since had the opportunity to hear your voice and be in contact with your work.

Honestly, I think that without that coincidence, it would have been very difficult for me, because I put in a lot of work and a lot of people didn’t believe in me. I think that the people who believed in me were the most humble, of humble soul but also financially humble. That’s why many people believed in me but weren’t able to help me in the way they would have wanted. And the people who did have the power to open doors for me and to give me opportunities simply didn’t do it, and now they have to recognize what they didn’t do at that time.

Thank you, Daymé, for sharing your story with us. I think we’ll leave it there, but before you go, you mentioned your admiration for the musical cultures of Brazil, Cuba and the United States. Can you leave us with the names of some artists from each country who stand out for you right now?

Well, there are many, so many. Too many. I like a lot of people from Brazil. Among those who are still alive I love Djavan, I love Maria Rita, I love Ed Motta, I love Jair Oliveira. There are a lot of young people who I heard in Brazil but didn’t have the opportunity to make a note of. That’s why I feel like I have to go back, again and again. There’s a band called Zuco 103 that I like a lot as well.