West Africa

Kris Okotie

http://youtu.be/qLwj9GSD0bwKris Okotie is currently one of the foremost televangelists in Nigeria, but the career of this canny performer first started in the early 1980s, when he was plucked from the relative obscurity of law school by kingmaking producer Odion Irouja, ascending almost instantly to the heights of pop stardom. Arguably the first solo star (i.e., not backed by a band) in Nigerian popular music, Okotie was the foremost performer recording for the independent Phonodisk records, and his massive success briefly upended the label hierarchies of Nigerian pop. After a few years in the limelight, Okotie quit music with a suddenness that mirrored his entrance, going back to school before finding his true calling as a successful minister, a post that he continues to hold until this day.

Okotie's music is a fascinating mixture of ultra-tight disco-style rhythm sections, and American-influenced singer-songwriter style--think Cat Stevens backed by Kool and the Gang, and you're halfway there. While that combination might strike a modern listener as odd, it reflects the musical moment of early 1980's Nigeria--worldly, funky, and moving quickly into a brand new sound. Where it might have ended had a military dictatorship put a stop to the scene is really anyone's guess.

William Onyeabor

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyL4c_LDCl0Mr. Onyeabor is, without doubt, a compelling and complex figure. This would be true even without the recent impact of (and recontexualization created by) the wildly successful promotional campaign surrounding the recent release of Who Is William Onyeabor, a compilation album drawn from much of the best of his '70s and '80s work. Like Okotie, Onyeabor turned to Christianity during the late '80s, and has since refused to discuss his earlier career in any real detail. That said, we know that he was a successful businessman first and foremost, owning significant interests in a number of different ventures. With the proceeds, he was able to invest in his own recording studio--not to mention the expensive synthesizers and drum machines on which he based his musical sound. Over a series of seven or eight albums, he developed a music style that moved from fairly conventional Nigerian funk to a futuristically computerized sound, particularly notable for its total abandonment of even the pretense of organic instrumentation.

That said, it seems important to view Onyeabor in context--social, musical and economic. While his refusal to speak of his former career may be a particularly intense example of the trend, the explosive growth of the Christian church in 1980s and '90s Nigerian society means that he is far from alone in his rejection of his former worldly conduct. Likewise, while his use of synthesizers might appear unlikely given much of the Nigerian music currently popular in the West, at the time, his more commercial songs (which in no way corresponded with his less synthetic ones) were well-known and widely played, with some of his tracks even used in government informational campaigns ("Hypertension" was used to help the Nigerian government raise awareness of high blood pressure). Furthermore, it is equally important not to forget the economic climate in which these records--and Onyeabor's personal fortune--were made. During the early '80s, Nigeria was enjoying an oil boom, and while the wealth it produced was being distributed anything but equitably, those who were successful in business tended to be quite successful in business. If Onyeabor is indeed to be included in this group (and there is every reason to believe he is), the records he created must be considered as anything but "outsider"--instead, they are the production of a man who had the money to pursue an expensive and time-consuming dream with little or no personal risk. Does that change the quality of the music? Not really--but it seems important to note that Onyeabor is probably more Howard Hughes then Delia Derbyshire.

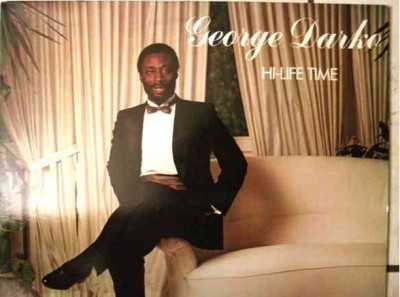

George Darko and Burger Highlife

http://youtu.be/yk_TOtzFJ7w Georges Darko is perhaps the best-known performer of what has come to be known as "burger highlife," after the place of its birth. In the '70s and '80s, a significant numbers of Ghanians emigrated to Germany, with a particularly large group settling in Hamburg. While there, musicians who had first learned their trade in the clubs of Accra were exposed to a world of electronics-infused disco and soul. Forming collaborative partnerships with German producers and musicians, burger highlife groups created a new high-tech musical sub-genre. As Ghana's economy improved and the musicians began to return home, they brought their new style with them. Young Ghanaians, seeking a cosmopolitan and up-to-date sound different from the music of their parents, would come to adopt the style as their own, pulling these elements into the center of Ghana's national musical idiom. Darko himself moved to Hamburg in the late 1970s, forming the Bus Stop Band, and eventually embarking on a successful solo career that continues to this day. To read more about burger highlife, see the Goethe Institute's page on the genre.South Africa

http://youtu.be/1RvfDkzUOosBrenda Fassie and the Bubblegum Sound

The cultural politics that accompanied the repressive apartheid regime in South Africa did not necessarily play out as one might assume. Rather than attempting to repress the culture of the various tribal groups, the system of apartheid often invested state funding in developing separate, "authentic" forms of cultural expressions, holding up these "pure" expressions as evidence of the potential for the system to produce a happily separate South Africa. An added wrinkle comes from the near total absence of exposure to other African musics among South African blacks. While American soul, r&b and disco was sold extensively, major African artists with transnational appeal were completely unknown in the townships and homelands. As a result, South African music from this period was both supported and stifled, aided by a large and well-structured industry while consistently held back by the apartheid's numerous restrictions.

In the face of all of this the bubblegum sound forged a complex cultural path through South African culture. On one hand, the music--full of love songs, slick arrangements, international influences, and sugary pop hooks--seems almost offensively escapist in comparison with the brutal repression of the situation from which it emerged. On the other, the very carefree brightness of the cosmopolitan sound almost serves as a wholesale rejection of the basic assumptions of apartheid--this was the music of young and stylishly modern South African cohort staking its claim to a sophisticated and urban future. Complicating the picture further, bubblegum also contained its own cloaked forms of rebellion--mixing languages (illegal under the statues of apartheid law) and embracing south African specific slang, it was the proud product of a culture that apartheid believed shouldn't exist. Yet, while these characteristics connected much of the music, bubblegum groups tended to be almost different as they were similar, including everyone from solo stars like Yvonne Chaka Chaka to bands like Splash or producers turned performers like Chicco Twala. The bubblegum sound was fed by a number of musical influences, and lacked the kind of internal cohesion of many other genres.

One of the most important musicians of the bubblegum sound is superstar diva Brenda Fassie, fittingly nicknamed "Madonna of the Townships." Beginning her career as a backup singer and later as the front woman in Brenda and the Big Dudes, Fassie had an enormous commercial smash with her disco-soaked track "Weekend Special." One of the first domestically produced pop songs to sell massive quantities in South Africa, the track woke up major labels to the commercial possibilities of South African artists. At the same time, while Fassie's early work makes sense within the rhythmic and melodic contours of bubblegum, she never claimed to perform, write, or record in the genre, and her music soon left the sound behind, adopting a more intense and openly political direction. Is Fassie a bubblegum artist then? It's hard to tell, suggesting that this may not be the best way to phrase the question. Instead of speaking of bubblegum as a genre, it might make more sense to speak of it as an era, in which a variety of pre-existing strands of South African music were put through a similar set of technological and musical changes.

To read more about bubblegum and its place in South African music, look for our upcoming interview with DJ Okapi from the Afro-Synth blog.

Ethiopia

Hailu Mergia

http://youtu.be/4R9Cki4ZrP0Hailu Mergia is a truly exceptional Ethiopian keyboard player. He first came to prominence in the Walias band, an instrumental funk group that backed up many of the legends of Ethiopian music, including well-known names like Mahmoud Ahmed and Tilahun Gessesse. After the military dictatorship of the Derg took power in 1974, conditions became increasingly harsh for Ethiopian musicians. On the group's first international tour, a majority of the band refused to return, staying in the United States, and reforming as the Zula band, a group that played the Ethiopian circuit in the U.S. During this time, Hailu became interested in the accordion music of his youth, a style that he hadn't played since organs replaced accordions in Ethiopian nightclubs during the 1960s.

Initially interested in producing a recording for his own collection, Hailu became entranced by the tonal and melodic possibilities of the synthesizers in the studio where he was working. Composing as he played, he added accompaniment to the the already written accordion lines, resulting in the creation of a full album which would eventually be released in Ethiopia as the instrumental cassette "Hailu Mergia and his classical instrument." While Hailu is not the only Ethiopian musician in this period to experiment with such a synthetic sound, his album stands alone as a marvel of subtle swing and elegantly dreamy melody. To read more about Hailu's music, check out our interview with him, as well as with Brian Shimkovitz from the Awesome Tapes from Africa label.