Blog June 18, 2013

Lebanon Journal: First days in Beirut

The remarkable thing about Beirut in the early summer of 2013 is how normal it seems. The tension one would expect reading international news headlines about the ever encroaching conflict in Syria would lead one to expect high tension, near panic. Instead, a Sunday afternoon stroll along the Corniche presents the picture of normalcy: families enjoying leisurely pleasures--ice cream, fishing, family, the ferris wheel. Conversations do reveal concerns, but also a huge variety of opinions as to what is coming, and, beneath it all, a profoundly philosophical sense of resignation. Anyone has grown up in this embattled has seen too much to panic until it's absolutely necessary.

Take Moe Hamzeh, lead singer of one of Lebanon's most successful rock bands, The Kordz. His childhood exactly coincided with this country's bloody civil war (1975-90; by the way, Moe hates that term--nothing "civil" about it, he says). Moe recalls school nights spent in the crowded basement of his apartment building during heavy fighting, escaping into the world of Pink Floyd's "The Wall" under headphones, and waking up to make his way to his school on the Green Line, with Bob Marley pumping a modicum of hope into his ears. These days, Moe is part of a new enterprise called Mercury Media, out to create a digital platform for a huge variety of Lebanese art--music of all sorts, books, films, and more. Our conversation was fascinating on many levels. Watch this site for more...

[caption id="attachment_10366" align="aligncenter" width="608"] Moe Hamzeh (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

I was very happy to meet another key figure in Lebanese music, Zeid Hamden of the band Soap Kills (1997-2006) and now Zeid and the Wings. The music is broadly rock/pop, with a decidedly Lebanese twist. Soap Kills made their name by placing oriental melodies (minus the quarter-tones) against spare electronic rhythm tracks--a radical idea in the late '90s, and one that caught on with young listeners in a big way. But, Zeid told me, of all the many radio and television stations available here today, there is not a single one that plays music by local bands creating this sort of original, local music. Not one. (The reasons for this are complex...still sorting that out.) Hence Zeid's embrace of the term "Lebanese underground."

If that qualifies as a movement, Zeid is one of its founders and flag-bearers. But a number of artists I've met reject the term "underground," as well as "alternative" to describe their work. Mike Massy, an unusual singer with a classical background and a gift for popular songcraft, simply wishes to be categorized as "music." It turns out that talking about music here is almost as tricky and contentious as talking about politics.

[caption id="attachment_10369" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Moe Hamzeh (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

I was very happy to meet another key figure in Lebanese music, Zeid Hamden of the band Soap Kills (1997-2006) and now Zeid and the Wings. The music is broadly rock/pop, with a decidedly Lebanese twist. Soap Kills made their name by placing oriental melodies (minus the quarter-tones) against spare electronic rhythm tracks--a radical idea in the late '90s, and one that caught on with young listeners in a big way. But, Zeid told me, of all the many radio and television stations available here today, there is not a single one that plays music by local bands creating this sort of original, local music. Not one. (The reasons for this are complex...still sorting that out.) Hence Zeid's embrace of the term "Lebanese underground."

If that qualifies as a movement, Zeid is one of its founders and flag-bearers. But a number of artists I've met reject the term "underground," as well as "alternative" to describe their work. Mike Massy, an unusual singer with a classical background and a gift for popular songcraft, simply wishes to be categorized as "music." It turns out that talking about music here is almost as tricky and contentious as talking about politics.

[caption id="attachment_10369" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Zeid Hamden with his career-making "groovebox"[/caption]

Much of my mission here involves Beirut's signature art music, most notably the work of the unrivaled queen of Lebanese song, Fairuz, and the legendary Rahbani family of composers responsible for nearly all of her vast repertoire. Making progress there. I've just received an invitation to an exclusive performance by Ziad Rahbani, Fairuz's son, and one of the most eminent living Lebanese composers and musicians.

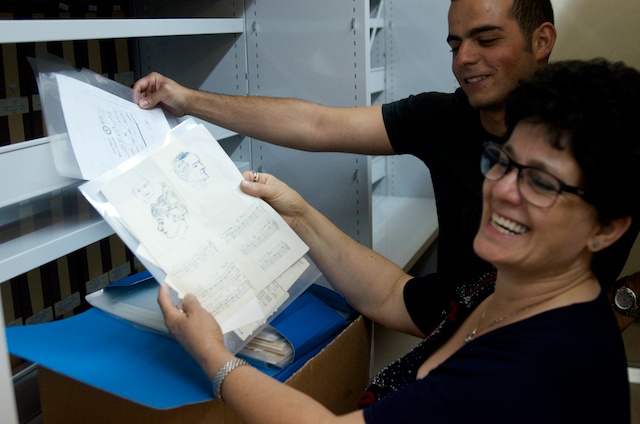

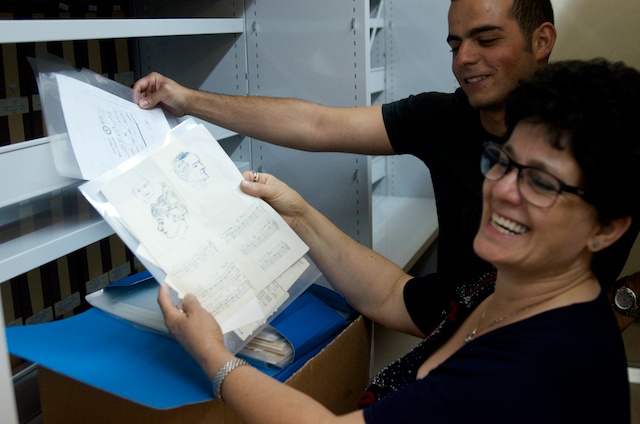

Along the way, I've been learning about another hugely significant composer, Zaki Nassif. When Nassif died at 84 (in 2004), he left behind over 1100 songs and many more poems, handwritten and piled up all around his house. This archive is now housed at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and when I visited it with with curator and Nassif biographer Giselle Hebbo and her nephew Michel, I learned that they have so far found recordings of only 250 0f those songs, and less than 100 are available to the public. Even still, Nassif is a national treasure, known to all Lebanese of a certain age. What's interesting is that so little of his work has actually been heard. For AUB, the task of commissioning new recordings and performances from this huge, unexposed repertoire will go on for many years. We will hear some of Nassif's works, including performances by Fairuz, and Mike Massy, on upcoming Afropop Worldwide broadcasts.

[caption id="attachment_10370" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Zeid Hamden with his career-making "groovebox"[/caption]

Much of my mission here involves Beirut's signature art music, most notably the work of the unrivaled queen of Lebanese song, Fairuz, and the legendary Rahbani family of composers responsible for nearly all of her vast repertoire. Making progress there. I've just received an invitation to an exclusive performance by Ziad Rahbani, Fairuz's son, and one of the most eminent living Lebanese composers and musicians.

Along the way, I've been learning about another hugely significant composer, Zaki Nassif. When Nassif died at 84 (in 2004), he left behind over 1100 songs and many more poems, handwritten and piled up all around his house. This archive is now housed at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and when I visited it with with curator and Nassif biographer Giselle Hebbo and her nephew Michel, I learned that they have so far found recordings of only 250 0f those songs, and less than 100 are available to the public. Even still, Nassif is a national treasure, known to all Lebanese of a certain age. What's interesting is that so little of his work has actually been heard. For AUB, the task of commissioning new recordings and performances from this huge, unexposed repertoire will go on for many years. We will hear some of Nassif's works, including performances by Fairuz, and Mike Massy, on upcoming Afropop Worldwide broadcasts.

[caption id="attachment_10370" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Giselle and Michel at the Zaki Nassif archive at AUB[/caption]

As I head out of town to visit musician and musicologist Nidaa Abou Mrad at Antonine University, to learn more about Lebanese traditions, I leave you with this. One of our programs will deal with the surprising story of the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil. It turns out that going back as far as the late 19th century, a large community of Lebanese (and Syrian) immigrants created something of a cultural revival in music, literature, theater and more--in Brazil! So I was intrigued to find that history reflected back in this recent event at AUB:

[caption id="attachment_10371" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Giselle and Michel at the Zaki Nassif archive at AUB[/caption]

As I head out of town to visit musician and musicologist Nidaa Abou Mrad at Antonine University, to learn more about Lebanese traditions, I leave you with this. One of our programs will deal with the surprising story of the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil. It turns out that going back as far as the late 19th century, a large community of Lebanese (and Syrian) immigrants created something of a cultural revival in music, literature, theater and more--in Brazil! So I was intrigued to find that history reflected back in this recent event at AUB:

[caption id="attachment_10371" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Rio at AUB![/caption]

Much more to come, including the opening of the Beiteddine Festival on Friday, proceeding in grand style despite all.

Rio at AUB![/caption]

Much more to come, including the opening of the Beiteddine Festival on Friday, proceeding in grand style despite all.

Moe Hamzeh (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

I was very happy to meet another key figure in Lebanese music, Zeid Hamden of the band Soap Kills (1997-2006) and now Zeid and the Wings. The music is broadly rock/pop, with a decidedly Lebanese twist. Soap Kills made their name by placing oriental melodies (minus the quarter-tones) against spare electronic rhythm tracks--a radical idea in the late '90s, and one that caught on with young listeners in a big way. But, Zeid told me, of all the many radio and television stations available here today, there is not a single one that plays music by local bands creating this sort of original, local music. Not one. (The reasons for this are complex...still sorting that out.) Hence Zeid's embrace of the term "Lebanese underground."

If that qualifies as a movement, Zeid is one of its founders and flag-bearers. But a number of artists I've met reject the term "underground," as well as "alternative" to describe their work. Mike Massy, an unusual singer with a classical background and a gift for popular songcraft, simply wishes to be categorized as "music." It turns out that talking about music here is almost as tricky and contentious as talking about politics.

[caption id="attachment_10369" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Moe Hamzeh (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

I was very happy to meet another key figure in Lebanese music, Zeid Hamden of the band Soap Kills (1997-2006) and now Zeid and the Wings. The music is broadly rock/pop, with a decidedly Lebanese twist. Soap Kills made their name by placing oriental melodies (minus the quarter-tones) against spare electronic rhythm tracks--a radical idea in the late '90s, and one that caught on with young listeners in a big way. But, Zeid told me, of all the many radio and television stations available here today, there is not a single one that plays music by local bands creating this sort of original, local music. Not one. (The reasons for this are complex...still sorting that out.) Hence Zeid's embrace of the term "Lebanese underground."

If that qualifies as a movement, Zeid is one of its founders and flag-bearers. But a number of artists I've met reject the term "underground," as well as "alternative" to describe their work. Mike Massy, an unusual singer with a classical background and a gift for popular songcraft, simply wishes to be categorized as "music." It turns out that talking about music here is almost as tricky and contentious as talking about politics.

[caption id="attachment_10369" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Zeid Hamden with his career-making "groovebox"[/caption]

Much of my mission here involves Beirut's signature art music, most notably the work of the unrivaled queen of Lebanese song, Fairuz, and the legendary Rahbani family of composers responsible for nearly all of her vast repertoire. Making progress there. I've just received an invitation to an exclusive performance by Ziad Rahbani, Fairuz's son, and one of the most eminent living Lebanese composers and musicians.

Along the way, I've been learning about another hugely significant composer, Zaki Nassif. When Nassif died at 84 (in 2004), he left behind over 1100 songs and many more poems, handwritten and piled up all around his house. This archive is now housed at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and when I visited it with with curator and Nassif biographer Giselle Hebbo and her nephew Michel, I learned that they have so far found recordings of only 250 0f those songs, and less than 100 are available to the public. Even still, Nassif is a national treasure, known to all Lebanese of a certain age. What's interesting is that so little of his work has actually been heard. For AUB, the task of commissioning new recordings and performances from this huge, unexposed repertoire will go on for many years. We will hear some of Nassif's works, including performances by Fairuz, and Mike Massy, on upcoming Afropop Worldwide broadcasts.

[caption id="attachment_10370" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Zeid Hamden with his career-making "groovebox"[/caption]

Much of my mission here involves Beirut's signature art music, most notably the work of the unrivaled queen of Lebanese song, Fairuz, and the legendary Rahbani family of composers responsible for nearly all of her vast repertoire. Making progress there. I've just received an invitation to an exclusive performance by Ziad Rahbani, Fairuz's son, and one of the most eminent living Lebanese composers and musicians.

Along the way, I've been learning about another hugely significant composer, Zaki Nassif. When Nassif died at 84 (in 2004), he left behind over 1100 songs and many more poems, handwritten and piled up all around his house. This archive is now housed at the American University of Beirut (AUB), and when I visited it with with curator and Nassif biographer Giselle Hebbo and her nephew Michel, I learned that they have so far found recordings of only 250 0f those songs, and less than 100 are available to the public. Even still, Nassif is a national treasure, known to all Lebanese of a certain age. What's interesting is that so little of his work has actually been heard. For AUB, the task of commissioning new recordings and performances from this huge, unexposed repertoire will go on for many years. We will hear some of Nassif's works, including performances by Fairuz, and Mike Massy, on upcoming Afropop Worldwide broadcasts.

[caption id="attachment_10370" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Giselle and Michel at the Zaki Nassif archive at AUB[/caption]

As I head out of town to visit musician and musicologist Nidaa Abou Mrad at Antonine University, to learn more about Lebanese traditions, I leave you with this. One of our programs will deal with the surprising story of the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil. It turns out that going back as far as the late 19th century, a large community of Lebanese (and Syrian) immigrants created something of a cultural revival in music, literature, theater and more--in Brazil! So I was intrigued to find that history reflected back in this recent event at AUB:

[caption id="attachment_10371" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Giselle and Michel at the Zaki Nassif archive at AUB[/caption]

As I head out of town to visit musician and musicologist Nidaa Abou Mrad at Antonine University, to learn more about Lebanese traditions, I leave you with this. One of our programs will deal with the surprising story of the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil. It turns out that going back as far as the late 19th century, a large community of Lebanese (and Syrian) immigrants created something of a cultural revival in music, literature, theater and more--in Brazil! So I was intrigued to find that history reflected back in this recent event at AUB:

[caption id="attachment_10371" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Rio at AUB![/caption]

Much more to come, including the opening of the Beiteddine Festival on Friday, proceeding in grand style despite all.

Rio at AUB![/caption]

Much more to come, including the opening of the Beiteddine Festival on Friday, proceeding in grand style despite all.