Leave it to three young European scholars to upend “world music” marketing conventions and create a product that defies current formats, pairing the newly emergent vinyl disc with a magazine offering a decidedly old-school deep dive into the history and personalities surrounding a similarly old-school and all-but-forgotten music genre from East Africa: Kenyan benga. On the one hand, FLEE’s maiden release seeks to revive and honor benga in an era of disposable music experiences by highlighting the genre with stories, recollections, analysis and socio-political history that even a keen African music fan may not be familiar with. On the other hand, the project seeks to connect the past with the present, by presenting just three (four in the digital release) carefully selected classic benga songs, first in their original form, and then “edited” by cutting-edge producers in Germany, England and Finland. The result is FLEE Issue No. 1: Benga Music, A Signature Genre from Kenya.

The name FLEE derives from the French phrase fuite en avant, roughly “to forge or escape ahead.” The phrase seems to capture both FLEE’s retrospective and future-oriented impulses. FLEE is the brainchild of Alan Marzo, Olivier Duport and Carl Åhnebrink, all of whom possess master's degrees, not in music, but in international relations and politics. Speaking over Skype from Berlin, Duport explains that the project grew out of conversations with Marzo. “We always had an interest in how soft power, culture, was shaping international, geopolitical relations.” The choice of music as a focus emerged naturally. Marzo produced music on the side. Duport’s father was an avid vinyl record collector, and he had grown up hearing stories about Nigeria’s Fela Kuti and other international artists. He notes, “Music is one of the most global forms of art. It was the one that seemed the most relevant, and we thought it would be interesting to make this bridge and this connection using music.”

These producers were well aware of the potential pitfalls. Duport says, “We were reflecting on how music consumption these days is going in the direction of streams, and how superficial it is becoming. We were disappointed by the lack of context given by so many projects these days, especially when we came to world music, as it is unfortunately known.”

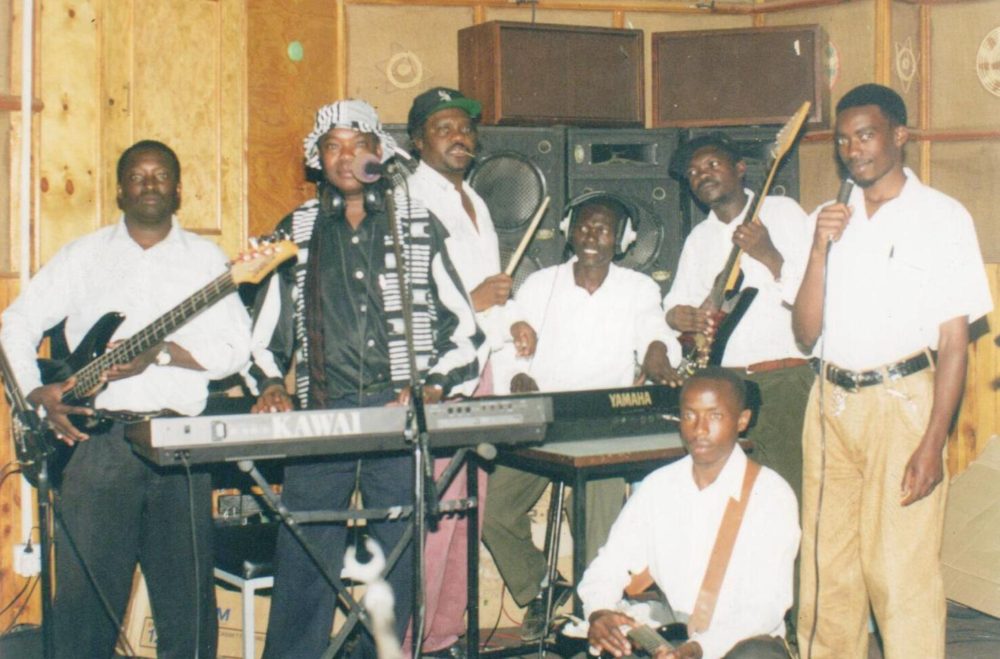

Once the decision to work with music was made, the first task was to identify a genre of deep significance to a society, one that was largely unrecognized amid the confusing onrush of international sounds. The idea was to imagine a new way of giving local music a home in the global marketplace. Marzo had been living in Nairobi, and suggested that benga seemed a good place to start. Once Åhnebrink joined the project, the three dug in, traveling throughout Kenya, interviewing experts and artists, collecting sounds and images, and learning all they could about benga music. Doug Paterson, Afropop’s longtime colleague and a widely experienced collector, compiler of and writer on East African (especially Kenyan) music, joined the project as an adviser. Paterson’s enlightening interview is a centerpiece of the magazine accompanying FLEE Issue No 1.

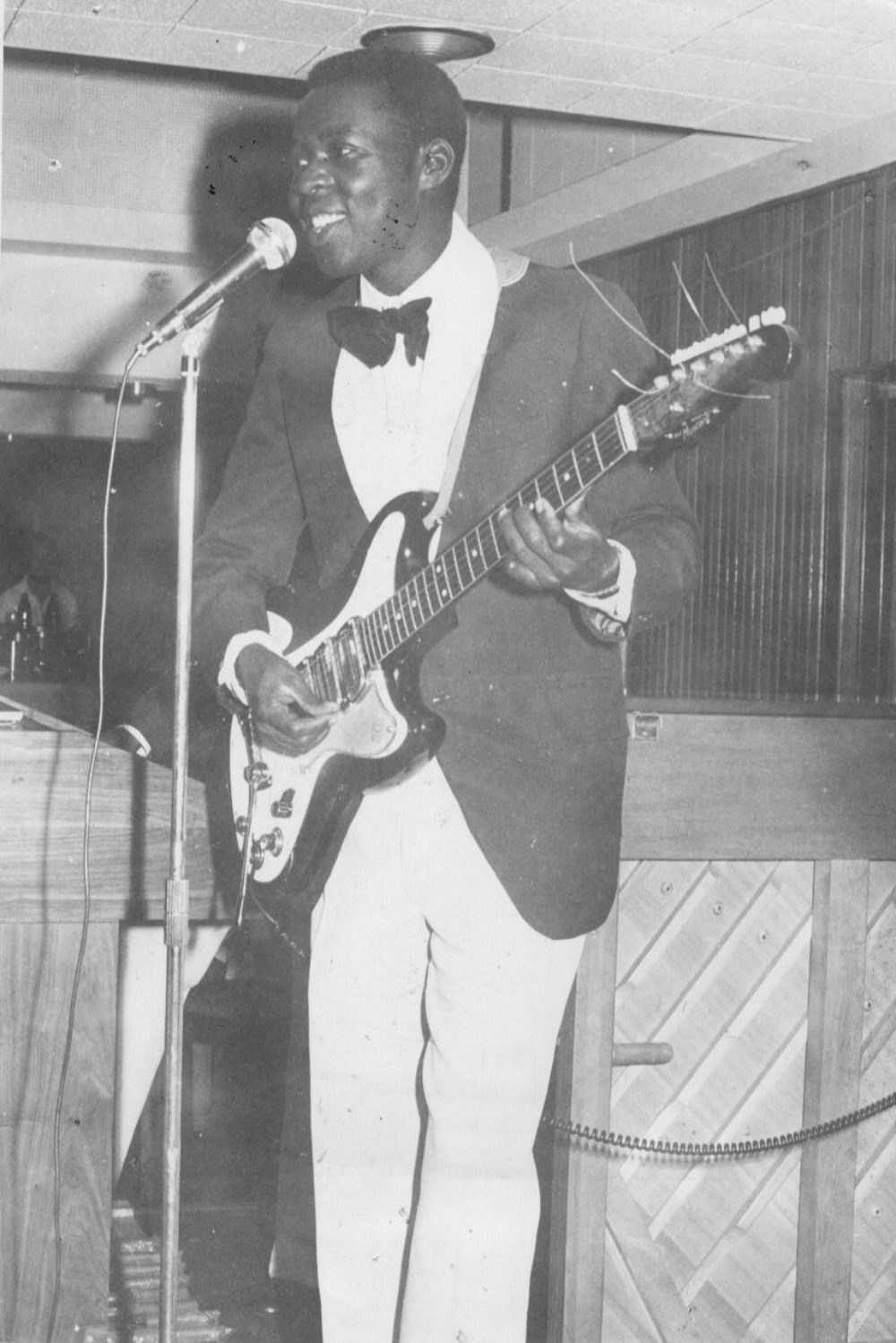

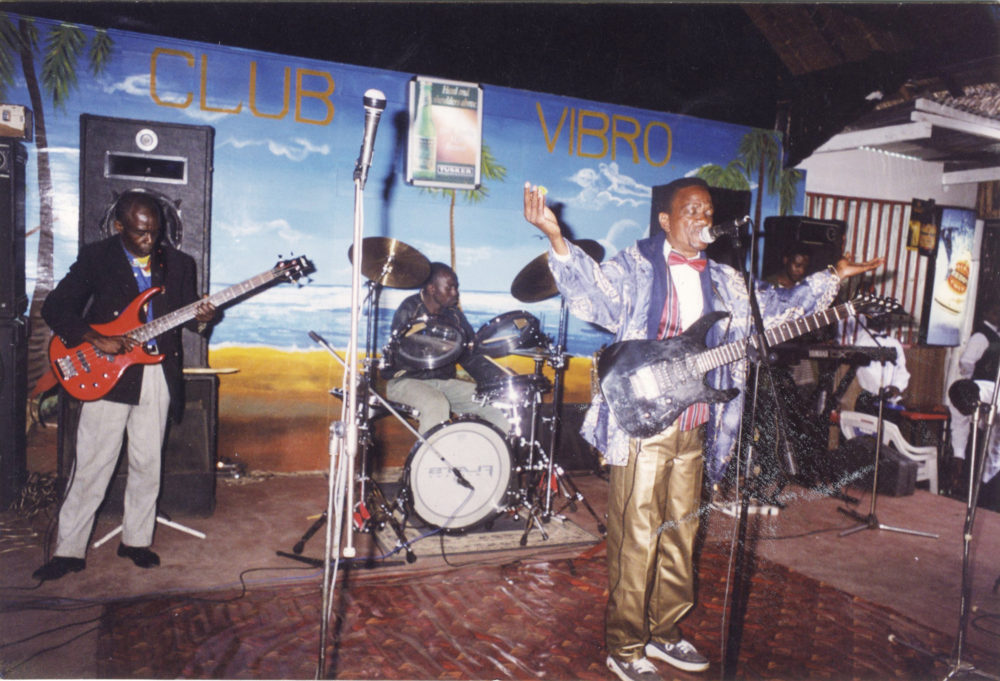

As academics new to the realm of African music reissues, these producers ask questions other compilers might not, such as, “How does one document a little-known African genre on a global scale without approaching it from a reductive and ethnocentric angle?” Part of the answer is to take time to listen to the insights of people who have lived the music’s history. The opening essay offers this description of benga: “Literally meaning ‘beautiful thing’ in the Luo language, benga finds its roots in Cuban music and Congolese rumba. The genre developed in East Africa around the 1970s and quickly became the federating anthem of all Kenyan tribes.” Kenya has some 68 languages, and the tensions and violence between its major ethnic groups are well known and continue to the present. In these pages, we learn how benga’s origins, influences, innovators tell the story of an emerging multiethnic society. In the early years of Kenyan independence, benga was widely recorded and performed in many languages, including Kamba, Kikuyu, Luo, Kalenjin, Kisii, Luhya, Embu and Meru. It was a unifying, hybrid sound that left room not only for a variety of dialects, but for melodic and rhythmic idiosyncrasies.

For all the detail here, there is more to say about benga’s role in Kenya’s ethnic politics. To some observers, the road to national unity is better served by adapting languages that de-emphasize ethnicity—Swahili and English—rather than those that boost potentially dangerous ethnic pride. That discussion begins here, but is ultimately beyond the scope of even this thorough and thoughtful volume.

Meanwhile, there is much to learn here about the music itself. Take music researcher Emmanuel Mwendwa’s description of benga’s guitar style as “a delicious bold attempt to mimic the quick push-and-pull strumming of the Luo eight-string nyatiti, creating a nimble interplay wherein both the solo and rhythm guitarists seem to ‘chase’ each other.” This is an apt characterization of benga guitar arranging, as opposed to its better-known Congolese counterpart. In the Congolese sound, the hierarchy of guitars—accompaniment, mi-solo, and solo—is strongly defined, with the soloist reigning supreme in the mix and the sonic landscape. One of the great charms of benga is the way bass, rhythm and lead guitars interact on more or less the same footing, intertwining playfully in an entrancing conversation among equals.

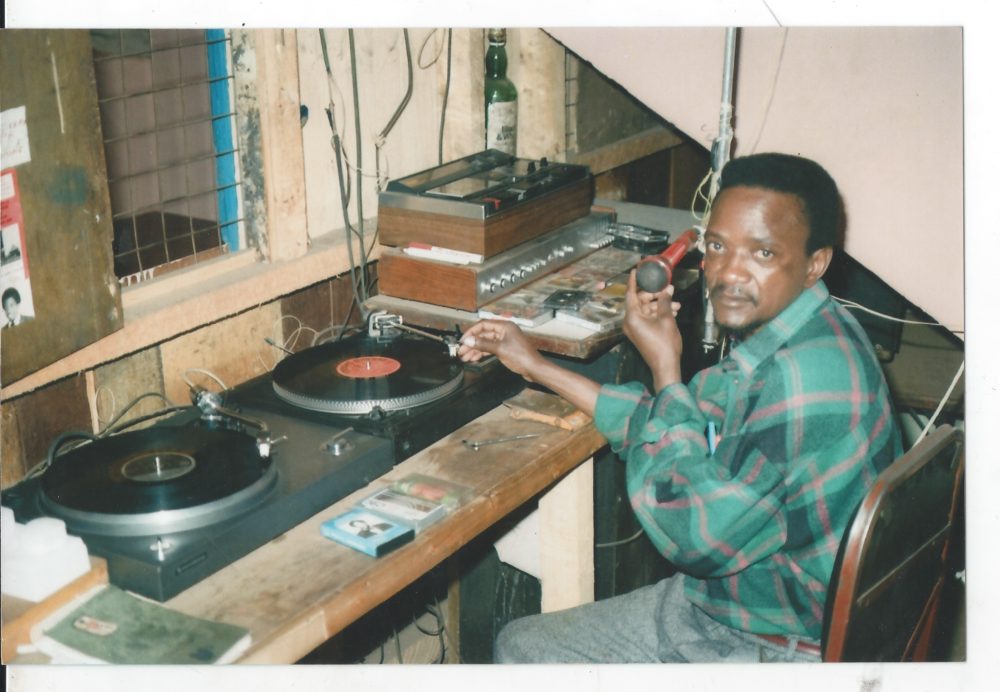

When it came to the selection of songs for the vinyl disc, the producers faced an enormous challenge. Rather than compile dozens of tracks, they wanted to present a very small number and focus the listener’s ear intensely on them. Naturally, the selection process was arduous. There are literally thousands of benga songs. There had to be levels of curation, first by the producers, then by the editors who would try to reimagine the songs in a contemporary way, and then by the producers again to select just four for the ultimate package. Some choices were easy. As Duport notes, “There’s bad benga music out there, as with any published popular music genre.” Many great tracks were rejected for technical reasons. “Lots of this content has been digitized,” says Duportt. “We had some vinyl, but in Kenya, lots of people got rid of vinyl when CDs arrived, even more than in neighboring African countries.”

As hard as this made the curators' job, it was even more of a challenge for the artists who would edit the tracks. The term is “edit” because “remixing” was not an option. Even if the producers had had access to the original studio tapes, benga songs were often recorded directly to two tracks. There was no instrument by instrument breakdown. This naturally limits possibilities, and the results are consequently quirky.

D.O. Misiani’s slow and sultry “Otieno Owing Ramogi” builds around descending vocal and guitar lines, alternating back and forth like a series of waterfalls that flow into a giddy, three-chord instrumental/animation section. U.K. producers and remixers Nik Weston and Rudy’s Midnight Machine graft on a tripping, off-kilter electronic drum intro and outro that bucks through the track, emphasizing the Congolese/Cuban clave feel in the final section. That’s an interesting choice. Another distinction between Congolese and benga guitar pop is the near disappearance of clave in the Kenyan sound, which takes more from the solid four-on-the-floor of southern African pop. A nice touch in this edit comes when the band drops out for a rhythm guitar break. The sudden disappearance and reappearance of those crisp electronic drums adds drama to the passage.

George Ramogi’s “Rapar Wuon Osimbo” makes the editor’s job a little easier. It begins with unaccompanied vocal harmony, and unfolds sweetly and lightly over gentle guitar parts, with just the tap of a bongo backing a leaping bass line. Finnish pop and jazz producer Jaakko Eino Kalevi keeps the intro and adds a fat synth bass line and drum machine groove to buoy that single bongo. He adds dub effects as drums drop out and sonic arrays of digital delay fill the open space. The song’s strong guitar line and the vocal keep the identity of the original track strong and present.

Personally, I’m not a fan of the way the electronic drums square the supple beat of the original tracks, nor the way these editors choose to replace those jumping benga bass lines—derived from traditional percussion with high and low aspects—with far simpler, foursquare lines. This is particularly true on FLEE’s own edit of the Victoria Kings’ “Pamisah.” The original showcases vocals and a delightfully bouncing bass line, against which the guitars rub together with elegance and eloquence—pure benga. The edit begins promisingly, mixing in a clip from an interview celebrating benga music. But as the song unfolds, the beat straightens out to something near to disco, and new guitar and keyboard parts—one sounding like a steel drum—radically alter the song’s character. The result is interesting, but it takes the sound far from the original benga.

Full disclosure: I’m notoriously hard to please when it comes to the art of remixing. I rarely find that the efforts of even the most celebrated remixers improve on the original, now matter how meticulously realized. FLEE’s urge to connect neglected styles with present aesthetics is admirable and challenging, perhaps to the point of impossibility. But I applaud the effort, and eagerly await the team’s next volume, which will focus on tarantella music from southern Italy.

You can find more on FLEE’s benga project and more available on SoundCloud, and YouTube, and on the website www.fleeproject.com.