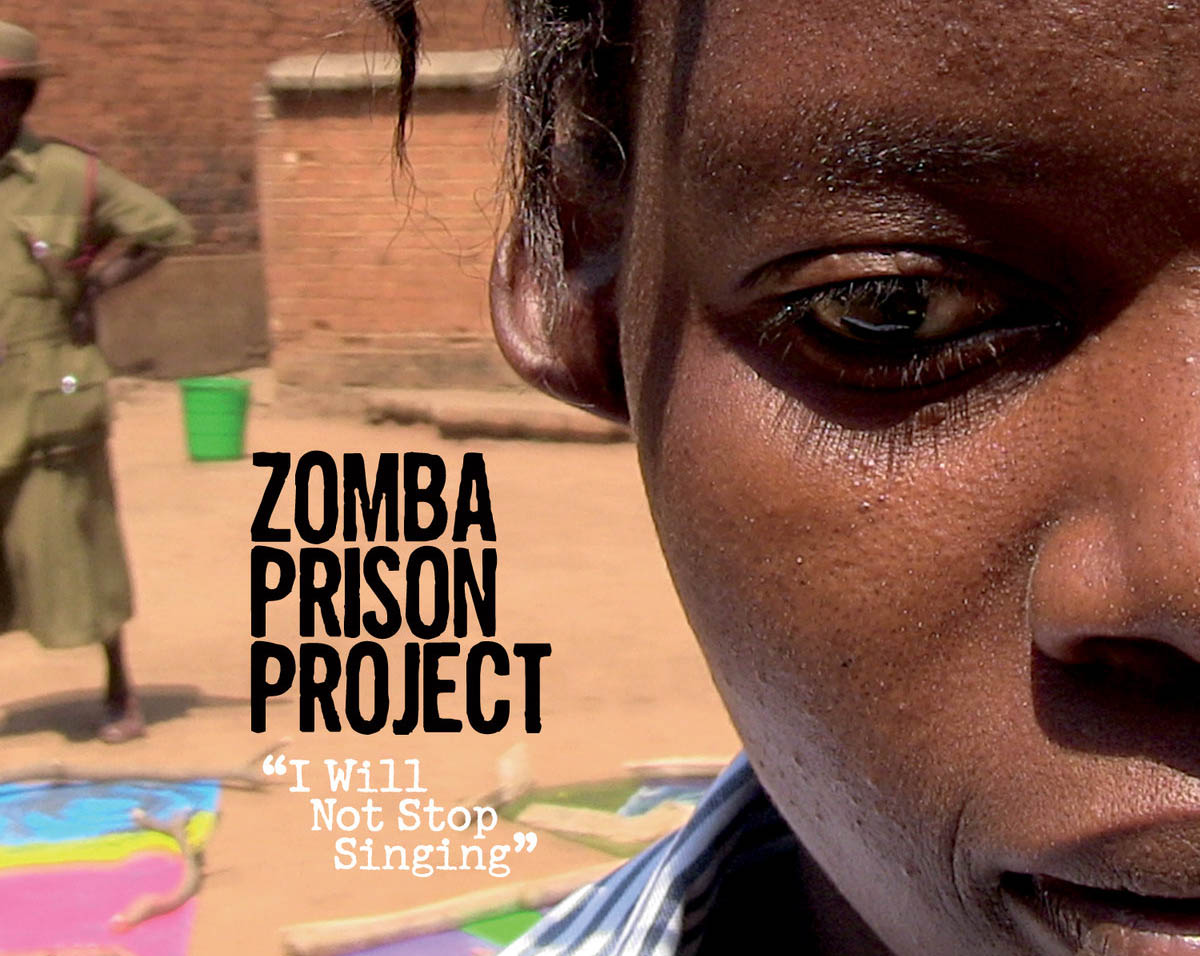

Ian Brennan is the intrepid producer behind the 2015 Grammy-nominated Zomba Prison Project, a groundbreaking recording session in a maximum security prison in Malawi. The original album, I Have No Everything Here, and the 2016 follow up release, I Will Not Stop Singing, are featured on Afropop’s program “Off the Beaten Track: Burkina Faso, Malawi and Beyond.” Producer Banning Eyre reached Ian by Skype at his home in Italy on Sept. 1, 2016. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Thanks for talking with us, Ian. To start, introduce yourself. Tell our listeners a bit about your background, and how you came to Africa, field recording, and ultimately, this project.

Ian Brennan: My name is Ian Brennan. I am a music producer and an author, and I've been producing records for over 30 years, mostly indie rock and roots records. I began doing field recording in the ‘90s in San Francisco, and my wife Marilena Delli, who is Italian-Rwandan, does all the photography and video for all the projects. She brought me to Africa for the first time ever, and we did a record with a group we met there, The Good Ones from Rwanda, and we haven't really looked back since on a quest to give a platform to underrepresented regions, countries, languages, cultures, etc. There are so many in the world, but we try to make a little dent.

Give us a little background on Malawi. It is a country Afropop has hardly covered in all these years.

Malawi is in southeastern Africa. It's a long narrow country that's wrapped on three sides by Mozambique, and the big feature there, and the big cross that they have had to bear, is that they have a beautiful lake, Lake Malawi, which led the missionaries and other colonialists there hundreds of years ago. They have overcome a dictatorship fairly recently, but they have a very peaceful history. They are known as the “warm heart of Africa,” because the people are known as being very friendly.

Warm heart of Africa. Of course that reminds us of one act we do know from Malawi, The Very Best, who named their first album that.

Yes. Unfortunately, Malawi has dropped to the number-one poorest nation in the world. A lot of the individuals there, particularly in the rural regions, suffer hunger shortages between the two crops. But it is just a beautiful, beautiful country. Chichewa is a very musical language, and some of the countryside is really amazing. In particular, Zomba is a very beautiful place. It's the former capital, and in many ways that brings the prison into even sharper relief. It is set on land that looks out over mountains in pretty much every direction.

Describe the prison, both physically and in terms of who is in it, and why.

Well, Zomba Prison is the maximum security prison for the whole country of Malawi. It is a fairly elaborate system of 33 prisons, I believe. The prison itself is a brick structure, and it has deteriorated over the years. It was built in the late 19th century. There are some reports on the Internet, that are incorrect, about it being built later. It was built to hold 340 people, and at any one time now, it has over 2,000. So the overcrowding situation is very, very extreme.

And in terms of the kinds of criminals housed there?

Well, it's a range. There are people there obviously for very, very serious crimes: rape and murder, and even double homicide or triple homicide. There are a lot of people there also for assault, burglary and theft, a lot of young men in particular. And then there are also people there, particularly among the female population, that are further victimized. They were victims of crimes that have been subjected to counter-activations, where their assailants turn on them, or their entire village turns on them. And it becomes very confusing about guilt and innocence in a lot of those cases, particularly because the court system there is conducted in English, the former colonial language, but the vast majority of prisoners are monolingual Chichewa, most of them illiterate in Chichewa. So that makes the legal proceedings very difficult for them to understand even what the charges are and what might be going on. So I would say that it ranges from innocence to the most severe crimes you can think of.

Wow. How do you get the idea to do this in the first place? What was the inspiration?

Well, I worked in prisons and jails in the United States. I worked in in-patient, locked psychiatric settings for 15 years, and I've been teaching violence prevention training for over 23 years around the world, but mostly in California and the United States. I've worked a fair amount in prisons and jails. I've also worked a lot with the homeless population in the Bay Area as well, when I was working at psychiatric settings. I just always had this idea of possibly doing a record in a prison, trying to represent people that were underrepresented.

We had gone to Malawi, Marilena and I, and met the Malawi Mouse Boys. And we had gone on to do three great records with them. They come from one of the poorest districts of one of the poorest countries in the world. And that's who we don't hear from usually. We hear from the people who are bilingual in English, who were educated at a university

Malawi mice!

somewhere, and that's wonderful. That's great that we hear from those individuals who might live in one of the two or three cities of the country, but oftentimes don't represent the majority. And they certainly don't represent the most severely disadvantaged. The Malawi Mouse Boys came from that kind of situation, where they are literally in a forgotten part of the country. Power lines that run between the two main cities from north to south literally fly over their village, about 20 yards away, but they do not have electricity themselves. I think that's a very stark, graphic example of the inequity.

We figured that if we were going to go back to Malawi, we needed to go deeper into the culture. And who could be more underrepresented than the Malawi Mouse Boys might be people in prison, who might not only be ignored or maligned, but even censored. That was the genesis of the idea.

I remember seeing the Malawi Mouse Boys in New York I don't think I have any of those records. Did they come out here?

Yes and no. They came out internationally. The first two records were on IRL, which is a U.K. label. And then the last record them out in March, I believe, or April. Omnivore put it out for North America. And they’re up there digitally, iTunes and so forth.

So I get your roadmap to the prison project. But how did you go about setting this up?

We had the good fortune of working with an NGO that Marilena knew there. Padre Gamba is a figure who has been there for decades who started one of the first, if not the first, nongovernmental radio stations and presses that were an integral part, a critical part, of overthrowing the former dictator. And he risked his life many times over in that process. And in fact, at one point, they destroyed his press. He does a lot of work all over the country really, but one of the places he does work is with the Prison Fellowship. He made the original introduction for us to the prison, and we did all the paperwork, the typical stuff of sending proposals and copies of passports and that sort of thing.

The person in charge of the prison told us that it looked good in theory, but he would not promise us access to the prison without meeting us. So we just had to take that leap of faith, which was to fly all the way there and then drive to the southern part of the country to meet him without any guarantee we would be given access. But, you know, we felt optimistic that we would succeed if we made that effort, so we did. We went down and met him. He was a very nice individual. The meeting was informal, and seemed more of a symbolic meeting. The only thing he said was that he'd noticed in the bio that I did violence prevention work, and he asked if I would also teach the prisoners and the guards some classes in conflict resolution while I was there, and I was more than happy to do that.

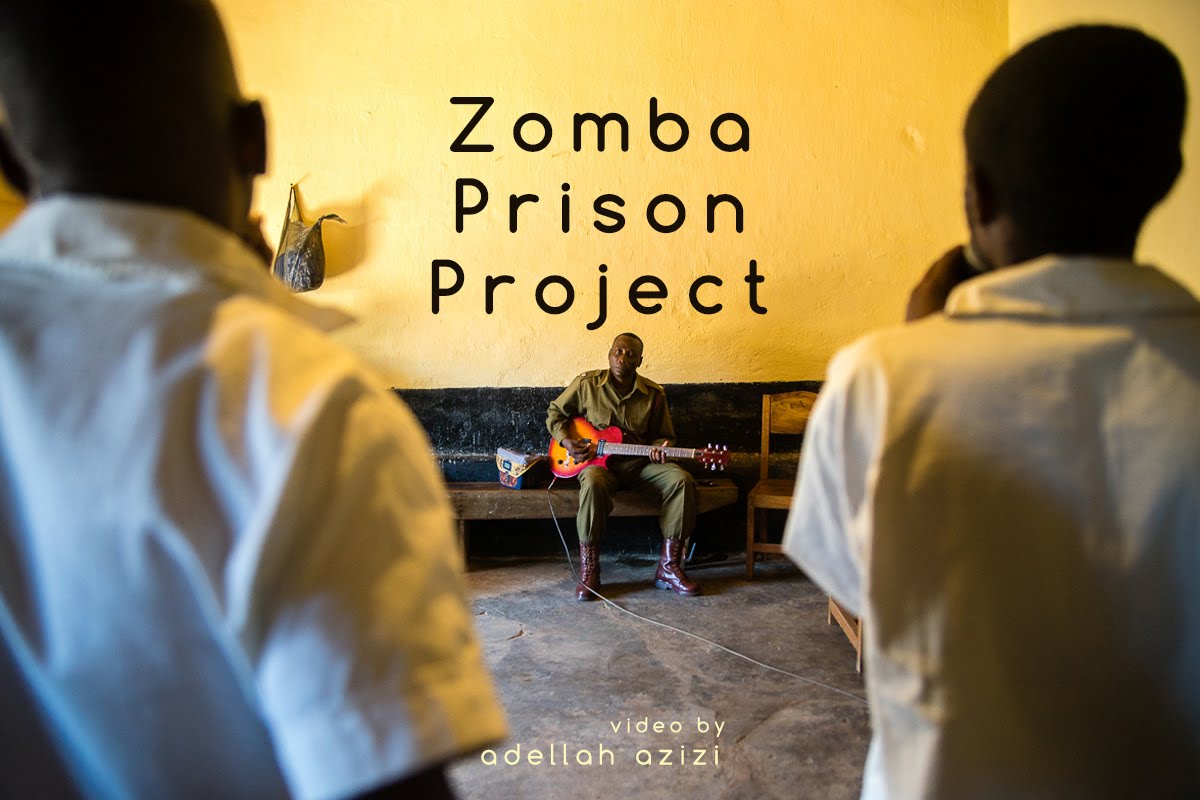

So from that point forward, we got quite free access during the hours that the prisoners are outside of their cells, which is basically from about seven in the morning until about 4 p.m. We had to convince them a little bit. There was a little bit of thinking that went on with them, where they wanted to be sure that they were going to be recorded well. They have an organized male band there, and they were much more scrutinizing of what it was going to do. In fact, we didn't record the band hardly at all. We recorded members of the band doing songs that they had written specifically for the record for the most part. But initially, they had some questions, but once everyone agreed, we really encountered almost no resistance.

Ian Brennan at work (Marilena Delli)

Ian Brennan at work (Marilena Delli)

Fascinating. It must've been an interesting process earning their trust. Had the band members been musicians in their outside lives?

Well, it's a real range. You know, there aren't a lot of opportunities for most musicians in Malawi, not unlike everywhere in the world. One of the guys did have a band, and they actually killed some people in another band to try and steal their equipment, and that's why he was in prison. But he is the exception in that he was a "musician" before coming to prison. For most of them, it is a skill set that they are developing as part of their rehabilitation, people who had been given a special privilege. So there's a wide range of talent. Some of them sang in church, and some never did music at all.

The big surprise for us was the women. They did a lot of communal singing and dancing but didn't write songs, and didn't consider themselves singers, meaning lead singers, and were very reluctant to participate. But in fact, in the end, with the first record, they contributed over half the songs to that first album, the women.

How long was the whole process of recording the first record?

It was a little over two weeks. We went in and we spent multiple days with the men. And we spent two days with women. But the bulk of the recording of the women all took place in one day when they were suddenly willing to step forward and try out their songs.

Amazing. That must've been quite a day.

It was incredible. It was one of those experiences that you hope for, to share that level of intimacy with individuals, and also just an experience of trust and seeing people succeed at what they're trying to do, and realizing they can do more than they knew. To see a group of people who were saying a couple hours earlier that they couldn't write songs step forward with songs that were amazing is a beautiful thing. It's something I would love to do every day.

Woman at Zomba (Marilena Delli)

Woman at Zomba (Marilena Delli)

I expect you knew going in how difficult it is to get a project like this noticed in today's media world. When you left after those first sessions, did you have a sense that you had something special here that might reach a broader audience?

Not at all. We do these projects as money-losing labors of love. When we left, as an experience, we knew it was a success. We knew we had a record, and we knew it was good, but whether it would ever be released was another question. I didn't see it as being any different than a lot of the other records we had done. I think The Good Ones records are amazing, and the Malawi Mouse Boys records are great. It wasn't a sense that this is so much better than any of those. The women, the last day we were there, literally danced us out of the prison. It was this long, joyous process. I felt like if nothing else came from it, it was a success. If it could be a record, if someone would release it, that would be great, and the few people noticed it, that would be awesome.

And that's kind of what happened. It took a while to find a label [Six Degrees]. When it came out, it got some attention, which was beautiful and nice, but not overwhelming, not so different than a lot of the other records we've done. And then, almost a year later, out of the blue there was this Grammy nomination. Then it was just a tsunami of media coverage, unlike anything I've ever experienced. Even when I won the Grammy for Tinariwen [Tassili, 2011], there was hardly an email, hardly a phone call. So to suddenly have dozens of emails all day long for about a month straight from all over the world was shocking.

What a great story. So beyond the lightning bolt personal experience for you, what was the effect on the project, the musicians, the prison, all of that?

Well, we have been back twice since the nomination to record the second album. I try as much as I can to look for patterns in what people say, so if more than one person expresses the same thing, it seems like maybe it's not an isolated case. One of the recurring themes that we have heard from people is that they were proud, and they very well should be. It gave them confidence. The individuals who thought of themselves as musicians, playing in the organized band, I think it gave them greater confidence to carry on—which in some ways is a mixed blessing, because playing music anywhere in the world is an extremely difficult thing. It's a hard thing to pursue. In some ways that's great, but in some ways it's a little sobering. But one thing that people really expressed was just amazement that they had been heard outside the walls of the prison.

It's like when we were danced out of the prison, I literally thought as we crossed that threshold, through the door and outside the walls, it may never go beyond these walls. And that was something a lot of them expressed. It was not so much that they were amazed and impressed that it was being heard in the United States or China or somewhere, but just the fact that anyone had listened to them outside the walls of the prison. For most of them that was a shock. I think most of them were very skeptical about what would happen with the record, if there would be a record. We tried to manage their expectations. There may never be a release. Because we did not know.

Now, with the success of the record, do the musicians benefit? Are they allowed to be compensated for the record?

Well, the record is a money-losing record, but we pay everybody always for every project at the outset.

So you were allowed to pay the musicians.

Well, it's a little indirect. We pay them, and it goes to the guards, and it goes into an account for the service that they then get when they get out, or they can maybe take a little bit out here and there for things like Sunday clothes or small food items, that sort of thing. So yes and no. We gave them instruments. We gave them food. We give them clothes. We've given legal support to quite a few of them. And all of them did get money. But there is always that lingering question, making sure that the money goes to the right hands. When we returned, some of them had been released. So we asked, "When you were released, did you receive your money?" And they said yes. So everything seemed to be very much on the up and up, and let's hope so.

When you went back this year, what was different?

You know, I don't know that anything was. If you compare the footage from 2013 to the footage we took this year, it would be hard to tell what was shot when. But there are differences. Some of the differences are that some of the prisoners have been released. One of the men who was there for life was transferred to another prison. One of the women who was involved in the first record died from health complications in the prison.

There is a new crew. The band itself is made up of a lot of different individuals, some the same, some different. But one of the great joys we had when we were there in January, and in May, but in January particular, is we went out and had lunch with four or five of the people that were featured on the first record and had been released since 2013. And it was really nice to be with them, in the city of Zomba, not in the prison itself, and at the end of the day to see them walk in four different directions to go home.

Wow. That must've felt great. In the sleeve notes to the new album, you comment on the press coverage that happened in Malawi after the Grammy nod. Tell that story.

Well, I think that all press coverage in the media can be a double-edged sword. And unfortunately, as I think a lot of us know, the standards of journalism have unraveled very quickly since the rise of the Internet. So you see evidence of that in the coverage of this story, where most people were looking for a very convenient, fictional narrative about how the Grammy nomination would have come about.

Most of them had not done their research, had not dug deeply enough to even uncover such basics as the fact that there were women involved in the record, and that more than half the songs came from the women, and that the men's band was not actually on the record. It was members of the band, but not the band itself. And also that I am not the same person who shares my name who created the show Glee. So, you know, what could be a more grievous journalistic error then to write about two people as if they were the same individual when they are not.

Ow. Were these international or local journalists?

I think it's the full spectrum, and you know, I would say to be fair and balanced, some of it came from just a lack of understanding of what the nomination was. You know, the majority of the people at the prison did not know what a Grammy was, nor should they really. No artist from Malawi had ever received a nomination. There was confusion about whether there would be a monetary reward if they want, and how they got nominated—you know, these sort of misunderstandings—what was on the record, what the record was. Some of it started there.

People really wanted to put forth the men’s band, which is great. They do a great service. They sing a lot about AIDS; that's how it was originally founded. But it was kind of hijacked by a desire to promote them, when the record was in fact not really them at all. And yes, even some major journalists had gone there and made these errors. But they were sort of compounding the errors that had already occurred. With each visit, with each piece, there were certain factual inaccuracies that just got repeated.

Yes. That is a very familiar story in world music journalism. There's very little fact checking.

People have these narratives that they want to put forward. They might be quite nice on a political level, but they are oftentimes not accurate.

We have encountered this problem many times over the years. When you say that there was an interest in promoting the men’s band, by whom? Where was that coming from?

Well, I think it was coming from more than one source, from the prison officials, the people that helped found the band, certainly the band itself. A lot of that is human nature, and understandable. We really believed, and a big part of our mission is founded on that sort of ancient Greek idea that those who want to lead should not be allowed to, and those that do not want to should be encouraged or forced to. You see that a lot, that sort of microcosm in that the best songs on these records come from people who were not songwriters, people who were shy, not the most boisterous, not the most skilled technicians. They have often had the most to share and the most to reveal.

So when the coverage came, a lot what appeared on the Internet was journalists going there and filming, making video of or taking pictures with people that had nothing to do with the record. They were the new members of the band. Often, people who had been part of the record, if pictured at all, were in the background. You could see that they were kind of shy and reluctant and weren't going to assert themselves.

Even when we went back, we gave Grammy certificates to both the men and the women, and also to the prison administration when we were there in May. And we gave some instruments to the women. We also provided some small instruments. But when we gave the Grammy certificates, the people that claimed them had nothing to do with the record, and the two women who were really featured on the record [sisters Irene Chibowa and Rhoda Mtemang’ombe] were literally seated at the furthest end of this group of people, just quietly sitting there.

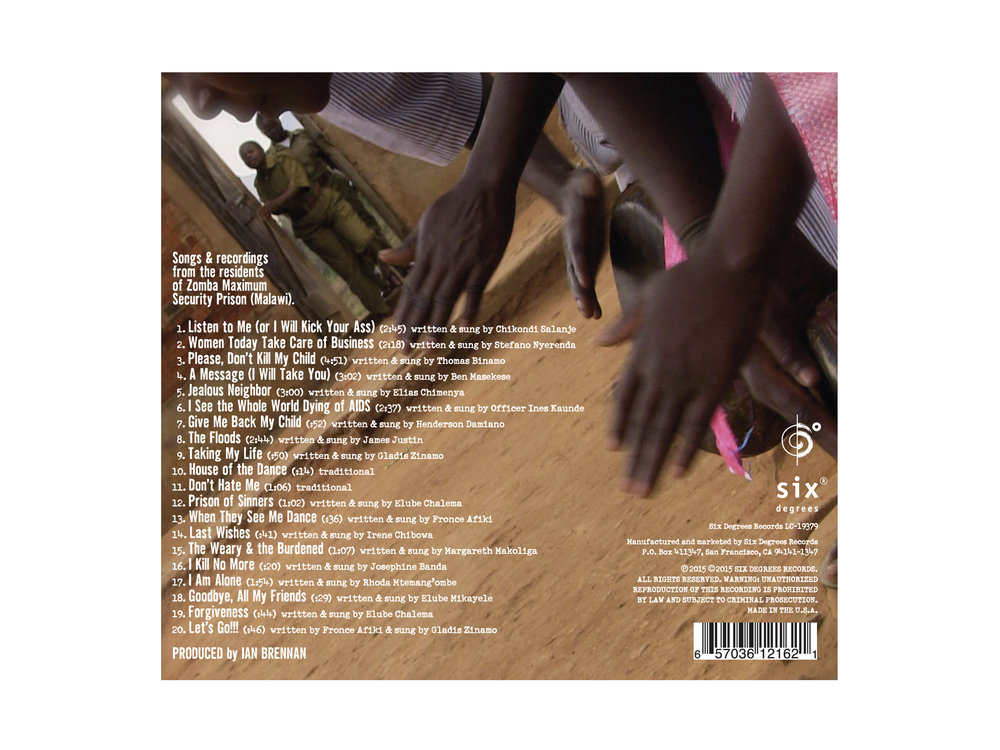

Tell me about some of the specific songs on the new album, whatever's interesting for you.

The first track, “I Am Done With Evil,” is by Vincent Saulos, who is there for life. He did a lot of harmony singing on the first record, but was not a lead singer. “I Will Never Stop Grieving For You, My Wife” is by Thomas Binamo, who wrote really what was the standout ballad, maybe the standout track, period, from the first album, "Please Don't Kill My Child,” which is about the phenomenon, rare but nonetheless a pattern phenomena, of people killing another person's child as a form of revenge. And this new song, “I Will Never Stop Grieving for You, My Wife,” was written on the very last day of recording in May, specifically for the album. He wrote it on the morning we recorded it. And it's just incredibly beautiful. He is speaking to his wife in the graveyard about how their children are O.K. He's going to take care of the children, and he will always miss her.

“All Is Loss” is a group song that has a really interesting low vocal part that was done by Agnes Chiwesa. We had recorded this one in January, and I didn't realize until we came back and made it that it was her also who had done this part. It's incredible. It doesn't sound like anything I've quite heard before.

That's a very powerful track. It has the rich choral quality I associate with southern Africa, but that low, heavy breathing is remarkable.

Yeah. It is one of my favorite tracks. And it is sung by the Muslim minority, and so probably there are some elements that are that might be unique because of that background that some of the women have.

“Sister, Take Good Care of Your Husband” is sung by Elias Chimwali, who also sang an a cappella track on the first album. He's just an incredible singer and when he goes to the high part of that song, it sends chills up and down my spine and brought tears to my eyes when we recorded it. “Ambush of the Slaves” is one of those songs that sung by someone who is not usually a singer: Chisomo Chipembere, the bass player in the male band, and whose bass playing is all over the album, but he’s not normally a singer.

That's interesting. The bass playing is wonderful throughout.

There are a few songs that are kind of a stripped-down version of the band, and that's one of them.

What about the song itself, “Ambush of the Slaves?”

Well, it's more of a historical allegory I mean, he's in prison and he's talking about the power they can potentially have, even when they are oppressed. “I Will Not Return to Prison” is sung by Chikonde Salanje, who also sang on the first album. It is a chant essentially. There are very few words to the song, except for repeating over and over again "I will not return to prison." And we recorded it in May and he was just released last month, so I hope that it's true. I hope that it's actually true for him.

Nice.

“Leave My Daughter Alone” is also by Vincent Saulos. Two of the big themes in a lot of these songs, and on other albums we've recorded over the years, are AIDS and HIV, but also a lot of concern for children. There are a lot of references to daughters and sons. Take care of them. Don't hurt them. And this is along those same lines.

“I Wonder (HIV)” is a song by Thomas Ndadabwa, who is Rasta, and has since been released.

So you've given us some updates on a few of the prisoners. Are you able to keep up with their progress?

We try to keep updated. It is difficult. Communication can be quite slow. Irene and Rhoda, the two sisters—we have actively working on getting their case reviewed and appealed since 2013. It's been very frustrating. It's taking forever essentially, but we are hopeful that at some point, they will at least have a chance to have their case reviewed. We don't know what the results of that will be. One of the women from the first album, Fronce Afiki, is now released. Her husband is in prison, and we are also working on trying to get him released so that he can be in the community with her and her children.

Ian and young friend (Marilena Delli)

Ian and young friend (Marilena Delli)

Do you think that their participation in this project and the attention that they perceived helps them in this process?

I don't know. Because of the Grammy nomination, there was maybe more of an awareness, both good and bad, within the country of what they had done. You know a lot of times with the Malawi Mouse Boys, or The Good Ones from Rwanda, they would come to WOMAD and they'd be on the BBC, oftentimes more than once, and they be written up in the Sunday Times or be on New Zealand morning television, and then they go home, and it was if they had never left. Literally no one knew what they had accomplished. It seemed very difficult often to get the local media to care. Kind of a “big in Japan,” or “never hero in your own hometown” phenomenon.

This is quite different I think because of the sheer amount of attention, and also the official aspect of an award, and the Grammys themselves. I know for certain it's not detrimental, and I hope in some cases it will be beneficial in their future.

I suppose they are the only ones that can really judge that.

Exactly. Exactly.

What do you see as the future of this project? Do you plan to go back?

I don't know. Marilena has deep roots in the country of Malawi, but also deep roots in Rwanda. Her mother is from Rwanda and survived three genocides there. Her father worked in Malawi as a charitable worker for almost two decades in the ‘60s and ‘70s and spoke fluent Chichewa. She herself has been there many times, and lived there before we ever even went. We've been back I guess four times now.

When the first Zomba Prison Project album received the Grammy nomination, we had a discussion with the label about: do you want to do a second record? They were asking me this. And my answer was, “No, I don't.” We had more than enough material from 2013 to make a second record, but really, these aren't commercial ventures, and I really thought it should stand on its own. I didn't want to dilute the purity of it. But, then we went back in January, and we went back in May, and by the end of that, I'm the one who contacted the label and said, “We have to put this album out. These songs have to be heard.”

So it came about very organically. It was not calculated on any level. So I guess it comes back to that idea of never say never. I don't know what the future holds, but we have a deep love and attachment to the country, and to the people there are. And if we can, we will do what we can to help. We continue to help with legal cases. We continue to make contributions where we can, as modest as they are, to individuals there. We hope there will be more, because music is a beautiful and healing thing. It can't change the world, and it certainly can't undo severe poverty, but it certainly can tip the scales in a slightly more positive direction.

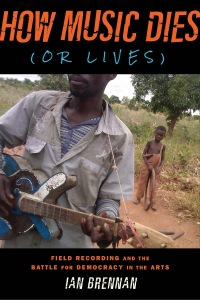

Well said. So finally, tell us about this new book you have.

It's my fourth book, How Music Dies, or Lives: Field Recording and the Battled for Democracy in the Arts, came out at the end of February this year. And again, it was something I never intended to write. In fact I was very opposed to the idea of writing a book about music. But I came around to the idea. It was my wife Marilena’s idea. On the one hand I think she was sick of hearing me talk about music all the time and being so opinionated about a lot of it. She said, “You have a lot of ideas, and some of your ideas are really good and you should share them with people. You've learned a lot over a lifetime of doing this.”

So I warmed up to the idea. The original concern for the publisher was that it would be too short, and then it ended up being too long. It is quite hefty. And in a sense that's good, because it's just designed to stimulate thought and debate. There are no answers in the book. It's just observations that hopefully get people to ponder what music means, and most importantly, to make sure that we continue to invest in it and recognize that popular culture is not trivial. We've been kind of brainwashed into believing that it is. It's actually extremely, extremely important. And a lot of good and bad comes from.

The inequity within pop culture, distribution-wise, is just staggering. We are from these "democratic" nations that are involved in one-way communication. Everywhere you go in the world, you hear English language media, but it's not reciprocal. In fact most countries from this world to this day, you'd be hard-pressed to find a popular music release, or a film, in the native language or languages of that country that's even accessible—even in the age of the Internet and digital downloads. Something of quality from those nations is hard to find. And so I think what you're looking at over 100,000 releases a year in the United States alone versus zero for most countries in the world, I just don't know how that can be defended.

Fascinating. Anything else you want to add?

No. Just thank you for all the great work you're doing at Afropop, and for everyone out there who cares about things that aren't coming out of Hollywood in Los Angeles and New York. We are all the richer for it.

Amen. This is fantastic work you're doing and it's great to talk.