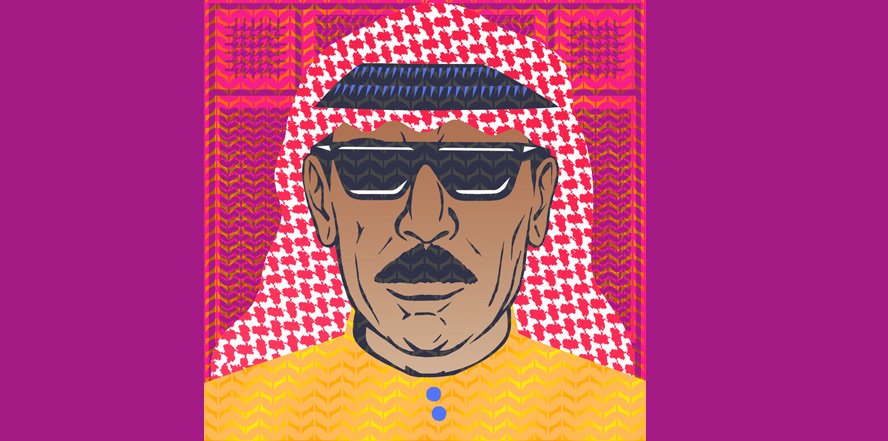

Omar Souleyman, turns out, has a beautiful smile. The poster for his Thursday show at Manhattan's Le Poisson Rouge, presented by the World Music Institute, gives you a good idea of the inscrutable public face that the Syrian musician has cultivated: stoic behind sunglasses and mustache. Even in his music videos, he is the eye of the storm—calmly clapping while keyboards peel out all around him. But live on stage, singing about tragic love and his war-ravaged home country, in brilliant flashes too quick for me to find in photo or video, Souleyman beams.

You might think Levantine dabke music's appeal would be limited to Syrian weddings where it originated, but the 50-year old singer was performing before a sold-out crowd. While there was definitely a contingent of enthusiastic Syrian fans, Souleyman's fanbase has grown beyond the Arab world and the Arabic diaspora, and has even transcended the “world music” tag. Working with outre electronic musicians like Four Tet, with an album coming out on Diplo's Mad Decent label on June 2, the Souleyman house was young, cosmopolitan, and there to dance.

It's a testament to the immediacy of his music that it works both at a wedding and in a Manhattan club—you pretty much can't help but move to it. Each song is anchored by a strong beat, while the keyboards spin out, sounding sometimes like the stringed oud, sometimes like bagpipes, sometimes like a house music hook. Thanks to this dynamism—one part folk music, one part club—it's fascinating to see the types of dancing that emerge.

@osouleyman has everyone on their feet #dabke #worldmusic #edm https://t.co/UEOp3fe8Jm pic.twitter.com/rwQMpcwWfu

— WorldMusicInstitute (@WMInyc) May 12, 2017

You've got the awkward sway of the people who come to live music to watch the performers. There's the individualized moving to the beat of modern American dance clubs. But even from the back, it was clear something was different: there's that twist-and-flick-of-the-wrist move that you see on dancers from India to Ethiopia.

After beginning with a ballad, with Souleyman singing off-stage and out of sight, the beat kicked in, and immediately the air filled with both people taking pictures on their phones and spinning cloths. In traditional dabke, the line leader spins either prayer beads or a knotted handkerchief, and in New York, denizens adapted it for a crowded club.

The floor was packed, but nevertheless circular pockets of people attempting the dabke kick lines orbited like whirlpools. Eventually groups found their way to the back where they could (cautiously) kick more freely.

Souleyman paced the stage, tucking the microphone under his arm, clapping in time and inviting our furvor. Eventually that led to dancers taking the stage—and being ushered off, and returning.