On Nov. 22, Afropop intern Deguet Kone, AKA Kinté, Le Prince Heritier, had a phone interview with Ivoiran reggae legend Tiken Jah Fakoly, in advance of his Nov. 23 concert at Gramercy Theater. You can read Akornefa Akyea's concert review here.

Deguet Kone: Good morning, Tiken Jah Fakoly, it’s an honor to interview you today. My name is Deguet Kone from Seguelon in the Kabadougou region in Ivory Coast and I will be your host today.

Tiken Jah Fakoly: Thank you, good morning. You said Seguelon?

Yes, Seguelon.

Oh, I know Seguelon.

For those who don't know, can you tell us, who is Tiken Jah Fakoly?

My government name is Doumbia Moussa. My artistic name is Tiken Jah Fakoly. I've released about 10 albums in Africa, Europe, and I will say in the world, because nowadays with the Internet, you have the possibility to be published everywhere. I am a reggae artist. I try to awake consciousness with my reggae. Like Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and many more elders who made this music a “fighting” music. I am an African, from Ivory Coast. That’s how I would present myself.

We would like to understand your journey from your childhood to the present. How was it for you to grow up in Odienne, Ivory Coast in the '70s?

It was cool, until I decided to sing. You know, in this region there was only one artist who was named Mamadou Doumbia, and for Odienne people and everybody in that region singing meant to get ready to go to hell. Music was considered satanic in a region of 90 or 100 percent Muslims. It was complicated, but I had to persevere. It was difficult but I grew up peacefully until I was sent (even before doing music) to my father’s village Gbéléban for me to stop dancing, because I liked to dance a lot when I was around 11 years old. I later on came back to Odienne when I was 18, and it was only then that I secretly started composing songs. I had to hide myself so that my family did not know; I did this for a while. My father passed away in 1987, when I was 19. After that I started to show my face more. I also formed a little group with some friends in Odienne, we called ourselves the the Djelys, we rehearsed and did our first concert in '93. So that’s how I started. It was very difficult but we had to persevere. We had to believe in what we did. A lot of people told me there would not be two great stars in Ivory Coast or just reggae stars in the world, that there was already Bob Marley, Alpha Blondy, and so I was wasting my time. But I had to persevere. We were able to make contacts, also with our work ethic we were able to stand out.

I see! We definitely understand your moves on stage.

[Laughs] Yes, I make a lot of movements on stage because I’m fighting for peace, to awaken consciousness. It’s a positive war, so I’m having fun. Those are the energies that animate me on stage.

I understand your experience of music being a taboo when you grew up, but in contrast, was education accessible?

Yes, indeed, education was accessible during the '80s and '90s, I was at school in Odienne before I got expelled to my father's village. Schools were everywhere, there were two schools in the village. It was the period when college students had some monthly payments as scholarships and the high school students, I think, were paid every three months. Those were the good times.

What do you think were the key factors in your journey that led you to be the renowned international reggae artist you are today?

I think it’s because I read some books at the time. I watched things on TV, I heard some things, injustices, inequalities that impacted Africans, from slavery to colonization, and continual colonization. It was all this that revolted me. There was also some stuff in Africa that revolted me. There were injustices among us. There were clan stories. If you were a griot you couldn’t get married with a noble descendant. If you were of noble descent you couldn’t get married to someone of griot descent. It was also these injustices that were the subjects of my first compositions. In one of my first songs, called "Djely," I denounced the injustices against griots. I was inspired by all sorts of injustices, and inequalities that I observed. Internationally, or around me, in Odienne, or Abidjan. So it’s really all this that inspired me. I also started to get interest by the social political situation in Ivory Coast in '95. When Houphouet Boigny died in '93 and problems started in '95 due to his succession, it was only then that I really started to get interested in my country’s socio-political situation. Inequalities and injustices were the key factors in my journey.

That makes a lot of sense. Would it be fair to say that you grew up as the Tiken Jah Fakoly that we know today? The revolutionary with a strong mind?

I know that I did not like injustices when I was a kid. I remember when I was 11, my first time in Abidjan for the summer vacation at my older sister’s, I did not like to see elders taking advantages of youngsters by hitting them. So even then I tried to put order everywhere. So one day my older sister sent me to become an apprentice to a tailor. Her goal was for me to not stay home all day. I also know that in Odienne every weekend I was told to go farming because of the same reasons. I found myself being the only child to go farming because I was trying to put order in the things that were not right. There were little stories like that. I would express myself even if it was toward elders. I’m not sure if my revolt started at this time but I was always conscious. I don’t recall in details but for example I was the only child to go farm when I had younger brothers. I remember I had to go sell second-hand clothes in Abidjan. I’m not sure what was happening at that moment but I was not a child that would just sit by and watch things happen.

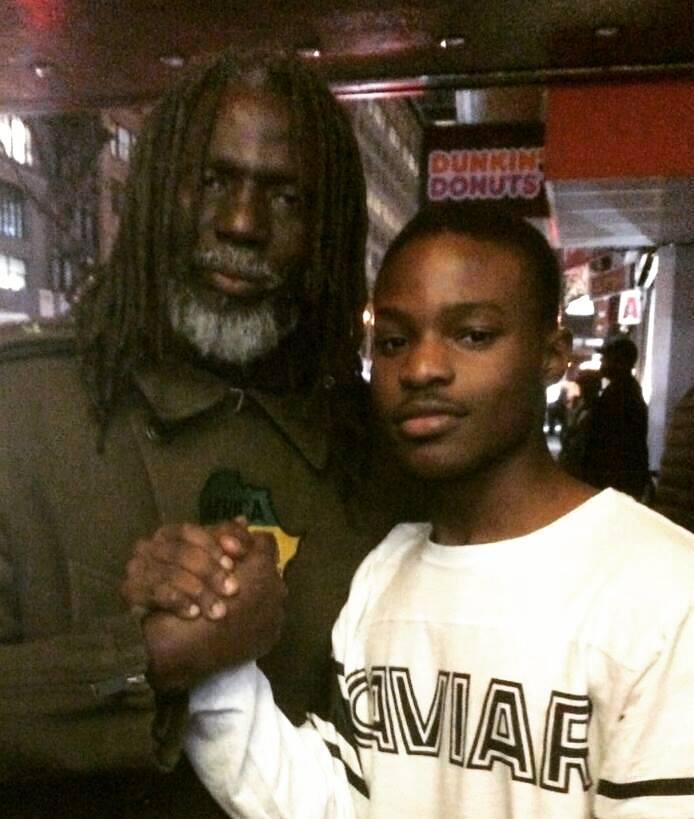

Photos by Sebastian Bouknight

That's fantastic. You earlier mentioned your group the Djelys, but what led you to separate from the group?

Let’s say that in the group I was the central pawn. Beside some French friends who later came on to help us, I used to finance everything. I was at the venues before the concerts with little brothers from the neighborhood cleaning up the seats. I was the most motivated. I think we were not making money at the time, I remember our first ticket price was 2,000 CFA [about $3.25]. At that time, I was not the oldest, some had responsibilities and couldn’t stay in the group. So when we recorded our first album in '93, the producer realized that the musicians were not at the level so we had them play, but he later on got new musicians to play after them. After our first album, we were not getting concerts so others got more and more discouraged. After that I traveled to France where I had friends who organized concerts for me. So I started performing in France and the others kind of gave up. Many of them were not going for a professional career. In Odienne we recruited everybody who knew how to play an instrument. People did not specifically come to make a professional career but to be able to perform at concerts. That’s what I realized. That’s how I stood out. But there wasn't a separation, there was no clash. It happened over time, some got disinterested, some went to do some other things. Only one wanted a professional career; he came with me to France and finally decided to be a solo artist. I think at the beginning the others just wanted to help us. One or two did not have the same luck, but from the studio recording we saw that the level was really low. We continued to rehearse but nothing changed.

I see, determination made it happen. I was listening to your latest album Racines, and I was wondering, what was the recording process? How did you choose the songs you performed? Did they have specific meaning for you?

These were songs that rocked my teenage years when I discovered reggae music. I also recently listened to them again, at the advice of my artistic director. I wanted to release an album in 2015 and when we listened to these tracks we decided to cover these songs because first they reminded me of my encounter with reggae music. Secondly, the messages were very current. Songs like “Is it Because I’m Black” have been very relevant for the past two or three years due to events here in the United States. Songs like “Get Up, Stand Up” from Bob Marley are very relevant. The world is going bad and people have to stand up to express it. So I listened to all these songs and I realized that the messages were still relevant. I chose to make this album for diverse reasons, also to pay homage to reggae’s golden age. A lot of reasons led me to make this album.

Considering these reasons, how were you willing to make your versions of these songs different from what was previously done?

Firstly, we had the asset of African instruments. Since 2007, with the album L’Africain, I fully started to use African instruments, so I knew we would have made an interesting difference between what was already heard and what we would be presented with African instruments such as the ngoni from Mali, the kora, the balafon and a lot of other African instruments. I think that all this too led me to making this album.

Fantastic. As Africans, we enjoy the music more when we listen to reggae music and we hear these African instruments. So, how was it to record in Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston and to collaborate with some great names in reggae like Max Romeo, Ken Boothe and U-Roy?

It was an honor for me to record with them but it was not my first time to collaborate with these great names Max Romeo, Ken Boothe, U-Roy, even Sly & Robbie. Since 1999 I’ve been going to Jamaica every three years. I recorded FrançAfrique in Jamaica in 2001, which was released in 2002. I also recorded Coup de Gueule there in 2004, which was released in 2004. Then I took a break and I went back to Jamaica in 2007 and 2010. So I was already in contact with them. I had recorded two albums with Sly & Robbie. So yeah, the collaboration was pretty cool. There was a very good ambience; they also thought that it was a great idea that an African artist cover these songs with African instruments. They were also happy an artist was covering these songs. One also told me that he was wondering why a Jamaican artist did not do a project like that.

Indeed, and most importantly bringing them to life again, not only using them.

Yes, they thought it was a great idea and they were very happy.

Wonderful. Well, we know you sing about different things including politics, revolt, education, emancipation and awakening, but what is the principal message are you trying send through your music?

My principal message is hope. To give hope to Africans and to tell the world the true story of Africa, because for me Africa is the continent of the future. Africa is the continent where everything has to be done. We can still buy land or houses in Africa for about three thousand dollars. Today in the rest of the world this money would be used to go shopping. Right now, I am doing a stop in Miami, it’s beautiful, everybody is happy. Here, it’s grey and the weather is cold. It’s is true that this is a great city, but economically, for me the future is in Africa because here everybody is happy during the summer because they can dress as they want, they can go out as they want while it is summertime all the year in Africa. And we also have space to build; all these buildings that you see here, there is a lot of space to build in Africa one day. For me Africa is just at its start. We only have 55 years of independence [in Cote d'Ivoire]. While others have 250 to 300 years of independence. So we are just at the beginning of everything. What I mean by that is that if you invest a lot in Africa, your children and grandchildren will work less to gain more. So my main message is to tell everyone that we are lucky to be African and that we should be proud to be Africans because Africa is the continent of future. Nowadays you see that every plane going to Africa is full. If you observe stabilized countries the planes are filled of people from the West and when it’s hard, people do not come but they do when everything is all right. So for me the principal message is to tell everyone that Africa is the continent of the future and that us Africans should be proud because the future is ours.

Great! In your song “Le Pays Va Mal" [The country goes wrong]" from your album FranceAfrique (for which you won an award in 2003 at the Victoire de la Musique in the category of Reggae Album/Ragga/World) you mention the crisis in your country, Ivory Coast. I quote: “Avant on ne parlait pas de nordistes, ni de sudistes, mais aujourd’hui tout es gâté.” [Before we did not talk about people from the north or people from the south, but today everything is messed up.] Do you think that the situation is better now in Ivory Coast?

I think that the country has been lifted up from the crisis but I think that division was again restored because politicians were clumsy. On the economic level the country is moving forward, but the population did not see the results of the country’s advancement, so people complain about the current leaders. We must do our best for the people to be empowered. It will go to the elections and try to change until we find somebody that will be the president of every Ivorian. I think that by searching, the people will soon find. The most important is that the people acknowledge that there are no more Dioulas or Bétés in Ivory Coast but there are Ivorians. We will win when we get on the same team. That’s the most important thing. We are slowly moving forward; we cannot say that everything is going well, because we can feel that the population is not satisfied, but we are in the process. We are moving slowly. We will have an election in 2020, maybe we will have somebody else. If not we will try again in 2025. It is by changing leaders that so-called stable, democratic, or developed countries found people who were able to change things at the right moments. We can also not say that nothing has been done in Ivory Coast, some things have been done but Ivorians were not 100 percent satisfied and I think that Ivorians will prove it at the next elections.

Definitely. Well, Tiken Jah Fakoly we will close this interview with this last question: You announced an upcoming EP called 3ieme Dose [Third Dose]. What should we expect from it?

Third Dose will talk about the leaders who want to stay in power for a third term. Our generation is opposed to any third term in any country, so I modestly say it, but as a spokesperson of this conscious generation it is important that I release a project to show where I stand. We’re working for 3ieme Dose to come out at the end of December for us to start the year with it. It will principally talk about the current tension in Ivory Coast and how politicians continue with these problems. It is also to tell every leader that wants to stick in power for a third term that we are aware! A first one is good, a second one is all right but a third one is not acceptable!

Thanks so much, Tiken Jah Fakoly, for this interview. I am really honored as a young artist from Seguelon, Odienne, Cote d’Ivoire to talk to you this morning, you are truly a spokesperson for the youth. It was a pleasure to hear from you. We hope that you will even go further and continue to help us spread the message so that we will be more inspired to move forward. Thanks to you and your team.

Thanks a lot “Ikonin” [in Dioula, “worthy heir of Koné."]