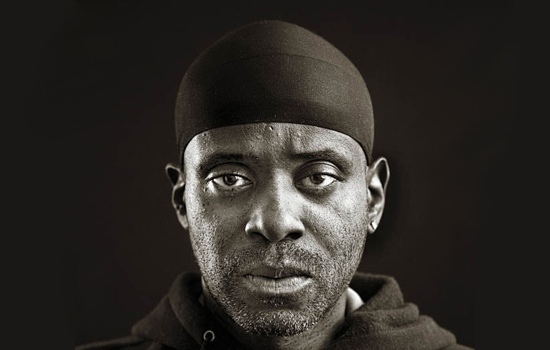

It’s usually hard to pinpoint the origins of a music genre, and Detroit techno is no different. But few would argue against the importance of the music of Juan Atkins in settting the tone for the techno revolution. His early recordings, under the name Cybotron, influenced a generation of young black youth to go out and make music with machines, and to make it funky. Afropop producers Wills Glasspiegel and Marlon Bishop caught up with Juan at the Submerge HQ in East Detroit while on assignment for “Midwest Electric: The Sounds of Chicago House and Detroit Techno.

Afropop Worldwide: To start, can you introduce yourself?

Juan Atkins: Ok, I'm Juan Atkins: Detroit Originator, Godfather, whatever you want to call me.

AW: You’re widely considered the father of Detroit Techno – take us through how this music came out of your experience.

JA: Well in '79, I was doing recordings in my house where I was using two cassette decks, a synthesizer and a four channel mixer. I lived in a rural area called Belleville right out of Detroit. So I didn't have any musicians that I could collaborate with or play with and I had to make different sounds, all the drum sounds, on my own, with my Korg MS-10. And eventually I got my first drum machine, a DR-55, and I used that.

That firs music I made was a collage of my influences: George Clinton, Funkadelic, Kraftwerk. At the time when I met my music partner Rick Davis, Kraftwerk had just released Computer World album. It was1980. So that kind of influenced the precision of what I was doing. I was doing music but it was not until I heard Kraftwerk that I heard those sounds, that mechanical precision introduced into this electronic soundscape. So we formed a group called Cybotron, me and Rick Davis. The first track that we recorded together was called 'Alleys Of Your Mind'. At Mojo played it on his station.

AW: Tell me a little bit about the Electrifying Mojo. Who was he?

JA: At this time there were only three or four other FM stations. FM was still real new. WGPR, the station that Mojo was on, was like 107.5, way on the right side of the dial. So Mojo was very very popular with the urban youth. He played all types of music – rock songs, pop stuff, but he made it work. On American radio it was unheard of to have all these different genres of music being played on one show. Because on rock stations that's all they played – rock songs. They didn't play any R&B music or Black music. So Mojo was very unique because he played like a half an hour of Jimi Hendrix, then back it up with half an hour of James Brown, then come with half an hour of Peter Frampton, America, and then Funkadelic, and then Kraftwerk. And it was just amazing, this DJ.

Mojo dropped 'Alleys of your Mind' on his radio show and it just blew up. It was like a breath of fresh air on the radio. And nobody knew that this was some black kids from Detroit making this record. They thought it was from Europe or somewhere.

AW: How has the city of Detroit affected your music and your creative process?

JA: I was born and raised in Detroit. This is a typical day in Detroit. Cold, rainy, overcast. If you've been downtown, all of these shops are closed. They're starting to open more shops but it's like an industrial ghost town. It's very bleak. But I love this city because of the bleakness. I think that the people here look for innovative ways to stay happy. Or to create different realities, because of the bleakness of this Detroit reality. And I think there's a lot of creativity that comes out of just being such a gray city. I think the city had the same effect on Motown.

AW: How would you describe exactly what your innovation was? What did you do that nobody did before to make techno music?

JA: The recordings that I started doing, along with my partner Rick Davis, were the first totally electronic recordings for dance music or R&B music especially. I think that this was the innovation, in the way of recording urban, or black music.

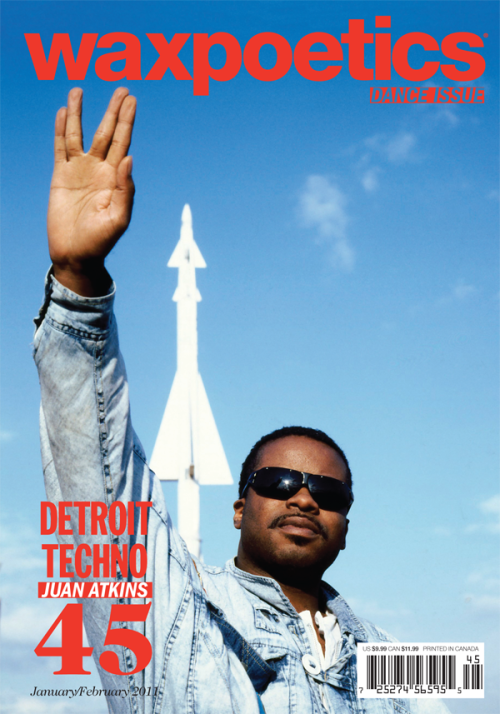

AW: How did futuristic imagery and futurism make it into your music?

JA: I've always like to wonder, to lay back and look at the stars and wonder about what's out there. I've been intrigued by all things having to do with outer space, space travel and time travel.. all of these things that were in science fiction novels and films. And it just came out in the music. It was a natural progression for me to make futuristic music.

AW: Can you tell us about how the name “Techno” got applied?

JA: Nobody knew what 'techno' was until I guess until the English label Virgin Records released this compilation called Techno: The New Dance Sound of Detroit. But I have to go back a bit.

You see, you have Chicago over here, and in Chicago they had kids that were having parties the same as we were. The only difference is Chicago was more predicated on a Philly International sound, which was disco, so all of the house music was a sort of an offshoot of disco music. They had kids making independent records as well just around the same time we were. And with Chicago being a bigger city, and being a more cosmopolitan city, they had more mix shows on the radio, more DJs on the radio. An/d they had a mix show called 'The Hot Mix 5,” and the DJs were playing Detroit records. And the thing is that when the record companies from England came to investigate this sound, they all landed in Chicago and discovered Detroit. They asked about my record “No UFOs,” and the Chicago kids told them, “That’s them Detroit boys.”

So they came to Detroit and Neil Rushton came up with the idea to do a compilation for Virgin and call it The House Sound of Detroit. And my track that I put on this record was called “Techno Music.” And they were like “wait a minute, if he's deeming this record “Techno Music” and all the rest of this stuff is similar sounding, let's call it Techno: The New Dance Sound of Detroit.' And hence, that album was released and the name stuck.

AW: People talk about Detroit as a story of decay: people leaving, industries failing. Do you see techno music, what you started and have continued as an alternative version of the story? Because we're talking about a music that has affected the world and continues to do so in profound ways.

JA: The auto industry had a metamorphosis. They let the Japanese come in and make cars better than they were making for a while. The American car companies got caught with their pants down for a minute. But that didn't have anything to do with the music. Yes, it created the landscape, it created the factories and everything. But that was my grandparents’ generation, that hinged on the auto factory. Yes, we're the children of that era and I guess that's why we're here. But the ups and downs of the auto industry didn't have anything to do with the music. And the reason why a lot of people are still here... there's an edge here that the environment creates that you cannot find anywhere else. The closest that I've seen worldwide is Manchester and Berlin. They have a similar atmosphere as Detroit. And that's why when stuff started happening in Europe, that's why Berlin and Detroit have such a kinship.

AW: Tell us a little bit about the imagery you put in your music.

JA: Well, for my second release, “Cosmic Cars”, I envisioned... imagine you're driving, you're on the freeway, and you just go and take off into space. Just visions like this.

AW: To what degree do you connect that kind of thing to P-Funk’s mothership, to Afro-Futurism and the idea of being whisked off to a better world?

JA: To me, it has always to a certain degree been about a certain escape, an escapist attitude. Because there are some times that you could be in a city like Detroit and it could get really bad. And you just want to fly away. And sometimes you wish you could dream, that you could just sail off to another time and space. A lot of my tracks allude to that kind of adventure.

AW: Could you tell us a little bit about the later period, when the Music Institute was happening. How did this music become a part of the landscape in Detroit.

JA: When the record companies came and they discovered Detroit and our records got put on these different compilations, we started to get invitations to come and play and DJ in different cities in the UK and Europe – Belgium, Holland, Germany. So we were able to bring all this new music back and we wanted to be able to have a venue to be able to play this music to our homeboys, our people here in Detroit. Hence, the Music Institute became a club. Derek was the resident DJ, . I played there regularly, Kevin played there regularly. And just being able to outlet this music in Detroit... and it was amazing because every week, somebody would be coming back in town and bringing us the latest stuff, grabbed from Black Market Records which was the big record store in the UK. And kids would come hear you play your set.

AW: What about the story of “Belleville Three”?

JA: The term Belleville Three stands for Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson. We all went to Belleville high school, we all lived in Belleville at the time. And that's how we all met each other.

AW: Did you guys work together, or was it more of a competition?

JA: It was friendly competition. I more or less taught them everything they know, pretty much. They would call me up, these guys, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson... they called me around the clock. I could never get sleep because it was all, “Hey Juan, I just got this S900 sampler, and how do you connect this thing to the blah blah blah.” I literally had to get up a couple of times at 4 or 5 in the morning to go to Kevin's house and show them how to make tracks. Eventually they become quite good at it. They started making records to a point where they didn't need my help anymore. Then it became sort of a competition...we'd get together and listen to what we've made, etc.

AW: How about now, what are you up to for the 2011 Detroit Electronic Music Festival?

JA: Last year I had a big party for the anniversary of my record label, so this year it’s going to be a bit smaller. As far as the horizon, I think there might be a feature length, dramatic film coming. I won’t go into that too much, though. Another Model 500 album soon and another tour. Those are the main things that are happening right now for me. The multimedia thing is large right now. Moving into music and video simultaneously will probably be a big part of the Model 500 experience after the album.

AW: Will you use any of your old analog gear for the upcoming album?

JA: You know I use a multitude of things. I like to keep it as a surprise as to what exactly is used.

AW: Those machines are in demand, you know, some bands are paying like $3000 for an original 808.

JA: You know what, though, by saying that, it's like “Hey man, I bought the first 909 drum machine when it first came out, I bought the 808 when it first came out,” so by me being an technological innovator, I gotta keep to my technological exploration [laughs].