Arabic art music shares one key characteristic with American jazz: an emphasis on improvisation, individual expression, but rendered with respect for and knowledge of a composed musical source. The rules and conventions diverge widely, but that common ground has proven irresistible to adventurous artists from both sides of the equation. As such, there have been many Asian or Arabic jazz projects over the years. But none quite like this.

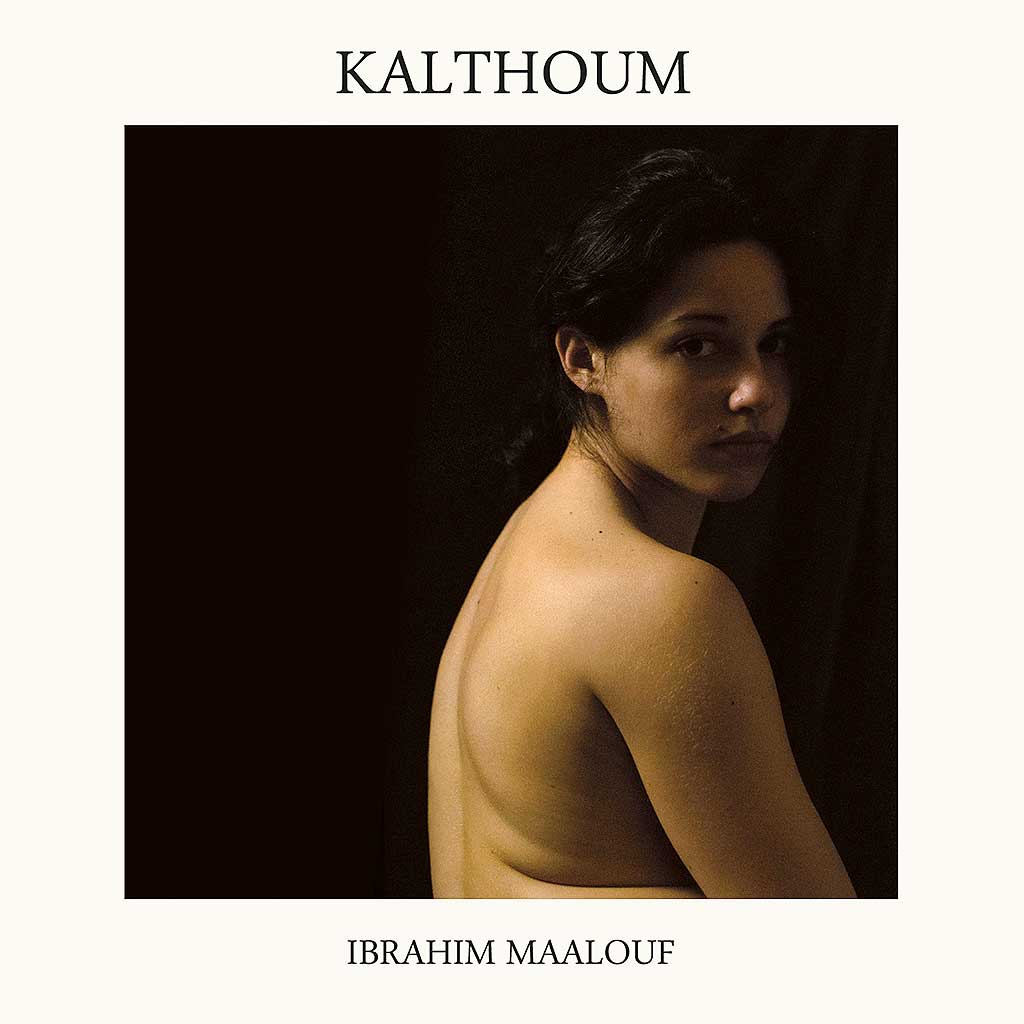

Lebanon-born, France-based trumpeter and maverick maestro Ibrahim Maalouf has been widely awarded and lauded for his inventive works in the past, including his 2011 homage to Miles Davis, Wind. Here, in a seven-part opus running over just over an hour, Maalouf delves into a single piece performed by the greatest Arab singer of the 20th century, perhaps ever, Oum Kalthoum [also Umm Kulthum]. The piece, “Alf Leila Wa Leila (The Thousand and One Nights),” was composed in 1969 by Balighe Hamidi, a principle composer in Kalthoum’s late career. Some considered his work lighter than works by composers of her earlier decades, who were more strictly loyal to the Arabic art music tradition, with its intricate rules of modulation between different maqam (modes), and use of microtonal intervals. But Hamidi’s large orchestral works were extremely successful commercially and remain deeply loved by Kalthoum aficionados.

In any case, this piece is well suited to Maalouf’s purposes, rich in themes and rhythms, by turns moody and exhilarating, and open to all sorts of creative arranging. The “Introduction” proceeds from a delicate opening on solo piano to a blustery, ceremonial blast of jazz with drums splashing, trumpet forging ahead with processional zeal, and ultimately, a Coltrane-like saxophone solo. So the music proceeds, shifting seamlessly between hard swing, ambling 12/8 time, and diligent march rhythms. The instrumentation is straight-up bebop—sax, trumpet, piano, double bass and drums. But the music is rife with the yearning, introspective modes and melodies of Arabic music.

Freewheeling solos intersperse these melodic passages, drawn directly from Hamidi’s composition. There is no human voice to utter words or evoke Kalthoum’s extraordinary sound directly, but the more one listens, the more one feels her spirit in these performances. Maalouf’s trumpet voice is perhaps the best example, profoundly confident and nuanced throughout. His understanding of the maqam system, and ability to render its complexities on his instrument, is legendary. While most Western listeners won’t exactly understand what that means, they can easily appreciate a unique and arresting sensibility in every note he plays.

Maalouf writes that combining Arabic tradition and Western orchestration involves “compromise.” The original Arabic art music tradition was all about melody and rhythm; it never envisioned the sort of block harmony that emerged in Western classical music and flourished to the limits of its possibilities in jazz. Kalthoum’s composers, especially the later ones like Hamidi, ran headlong into this contradiction and the compromises they made earned them both acolytes and critics. So you might say Maalouf stands on solid ground in embarking upon his own adventure in civilizational compromise.

One emblem of Kalthoum’s performances was the ineffable experience of tarab, a kind of transcendent emotional state that both musicians and audience can experience when the chemistry of performance and improvisation come together perfectly. Whether Maalouf and his colleagues in fact deliver the experience of tarab, I’ll leave to others to determine. But it is a worthy goal, and one very much in tune with the aspirations of improvisational jazz. Kalthoum is much more than a novel experiment in jazz. Having listened many times with deepening appreciation, I suspect it may be remembered as one of the more inventive and important jazz works of its time.