Living Traditions

Discussions on Traditions and Venues in Egypt.

Over a month in the summer of 2011, Afropop’s Banning Eyre and Sean Barlow researched a variety of traditional music scenes in Egypt. The most accessible folklore in Cairo is tourist fare, Sufi dervishes at the Caravanserai in old Cairo, or music and dance ensembles at hotels or in Nile cruise boats. For the most part, we avoided these venues and looked for music performance happening either in local settings for local people, or in one of Cairo’s intimate venues geared towards traditional music, Makan (home of the Egyptian Center for Culture and Art) or Tanbura Hall (run by the El Mastaba center).

This feature introduces a few of the acts, traditions and venues we encountered in Egypt, including photographs and excepts from interviews. See also our interviews with Michael Frishkopf and Mahmoud and Yasin El Tuhami on the Sufi saint festival (moulid), and Scott Marcus and Kamel Bahlol on the zaffa wedding procession.

Beshir

We caught Beshir’s contemporary take on music from Aswan (in Upper Egypt) at the Cairo Jazz Club. A nightclub where couples drink and dance and take an interest in unusual live bands is a rarity in Cairo. And Beshir’s sound was provocative and soulful. We await his first CD! Here’s a bit of what he told us in an interview at a Cairo café a few days later.

Beshir: I was born in Cairo, but my origins are from Aswan. That's where my parents were raised. And we kept relations between Cairo and Aswan. We used to go all the time to see the family. And that's where I was introduced to the Upper Egypt folkloric music. From then, I discovered my passion for this kind of music and decided to introduce it in a different way. I am a singer, and I interpret folkloric music, but trying to put a modern twist on it. So I would say it's contemporary, folkloric Egyptian music.

I think the music of Upper Egypt plays a big role in Egyptian music. Although my music is not exactly from Nubia, not Nubian music, it's really a mix between Nubian, African, and Sudanese music. I come from a family called Jaafra ,which is not Nubian, but it is a big musical family in Aswan. Jaafra music is basically a type of cultural music. It comes from a specific kind of folklore called kaaf nameem. Nameem is a type of art of storytelling, where you're telling a story without music. It's kind of singing and telling. They sit in a group, and improvise, telling a story, each one commenting on what the other has said. The most famous old song from this nameem type of music, the classic song, is called "Nana’i El Ganeina," which was performed by Mohammed Mounir. Then it was famous even here in Cairo and other cities.

I'm also inspired by other types of folkloric music that comes from Sinai, and other parts of the Red Sea, and still from other parts of Upper Egypt, Luxor and other cities. So my target and my aim is to mix all this kind of music and present ir in a contemporary, modern way, so they can be some kind of new contemporary folkloric music that people all over Egypt could listen to and understand. It is really essential for us as Egyptians to know our origins, and to put our traditional and cultural music into conservation again, and to try to grow it up in another way. It helps you to know who exactly you are, where you come from. It's spiritual. It helps you to be yourself.

Banning Eyre: If you listen to the radio or watch television here, you don’t hear much, if any, traditional music. Do you think that in this time of revolution Egypt is going through now, people might become more open to and interested in music like yours?

Bashir: I think so. I think Egyptians are going to be more into cultural music after the revolution, because I think the revolution helped them to be more Egyptians, to be proud to be Egyptian. So the interest is going to be more into knowing their origins, including the folkloric and cultural music. I really hope and believe this is going to happen, but it needs time, and we need to put more effort into it.

Jaafra: Sayed Rekaby

At Makan, one night, we heard one of the most respected singers in the Jaafra tradition Beshir speaks about. The performance was wonderful, and we spent some time speaking with the singer, Sayed Rekaby.

Sayed Rekaby: I am from the Jaafra tribes in Aswan, which are Arabic speaking tribes. I am a singer and a musician. The music of the Jaafra people is similar in some ways to Sudanese music. The major difference being the language.

B.E.: What are the instruments in the ensemble?

S.R.: Originally, the tanbura, a lyre, was used, which is a larger version of the simsimiyya. Sometimes now the simsimiyya is also used, and frame drums. Nowadays, there's more emphasis on the oud. The tanbura, the Pharoanic lyre, isn't in use quite so much for two reasons. Noise pollution, making the oud easier to hear. And then, also just the development of people's musical tastes. And on the oud, and on the tanbura as well, they play a pentatonic scale. But they will also sometimes play the microtonal scales, closer to Arabic music. But even when we use the oud, we stick pretty closely to our own language, our own culture, our own poetry, so that even though the instrument is closer to Arab Oriental music played by Umm Kulthum and Abdel Wahab, Abdel Halim, and all of those people, we still retain our flavor by keeping the poetry the same, the language the same, and also, melodic way, not moving too far into microtones.

B.E.: What is distinctive about Jaafra music?

S.R.: There is a type of improvisation that happens on stage. Even though certain melodies have been passed down from generation to generation, the performer is still interacting very much with the audience, in a way that harkens back to the way Arabic poetry used to be generated. It was part of common speech. It would be one poet addressing a group of other poets and then sort of volleying the poetry back and forth between them. So that happens today in this kind of music by having the performer be in tune with the audience and producing that type of interaction, feeling what they're looking for or what the performer is inspired to do in the moment, and improvising on that.

The music of Aswan is known very well to people from that area. I have done a lot of work trying to spread that in Cairo and make it more recognizable. There is a song called "Nana’i El Ganeina,” which was recorded by Mohamed Mounir. This is originally my song. I recorded it in 1990 and it had a different style, a different flavor. It was stolen and we recorded in a way that didn't really keep true to the tradition. The song was originally called "Nana’I El Ganeina," which means "the mint from the garden." When the song was released in a popular way, there were words added that mean, "of loving girls" or something like that. This was a song from the days of King Farouk. When he would go to visit Sudan, and then go to Egypt, the girls would apparently sing this song to him. In Cairo, I was one of the first people really trying to make Jaafra music popular. And this was one of the songs I've had some success with, and then it was recorded by other artists. My issue isn't so much that they recorded it, but the way that it was translated to the Egyptian audience. They weren't getting something that was folkloric and traditional. They were getting something bastardized, very far from the original.

One of the issues is the Egyptian media, which doesn't give traditional and folkloric artists any due in terms of writing about their music. Egyptian media isn't looking to try very hard to figure out what is interesting to talk about. It just wants to have its one page on the arts and call it a day. It is a shame that there is more interest coming from abroad. I am going to improvise a poem about this for you now.

Art, you have been betrayed by the words that they say about you. Those of them who are faulty out of mind, they think they understand. Singing in Egypt is now a tiresome to those hearing it. Instead of a state of taarab, they have moved away from the people And what is dear has been cheapened Now, anyone fit to chew gum is fit to create art and music. Art has been betrayed.

B.E.: So, we are here in the middle of all this traffic and chaos in Cairo. But if we were seeing your group in Aswan, maybe at a wedding, what would it be like? Give us a picture of the scene.

S.R.: We would be by the Nile. The sky would be covering us. It would be just an open, green, very quiet spot. The difference between a concert that happens there and a concert here is that I am not as charged here as when I'm in Aswan. Especially because a lot of the improvisation takes its strength from the natural surroundings and all that stuff. So even though I try to take the audience for an hour or an hour and a half to Aswan, I am not 100% there, because I am not home. I'm doing it in these different circumstances that don't allow me to be as present as I would hope to be.

In Aswan, we are asked to do a lot of things. Some of them are things like weddings, funerals even, social occasions. And then there are events that are set up more like a concert with performers and audience. Basically, we are artists who are part of a community, so if you invite us to something as artists, you can only expect art to be produced in that moment. If you put a flower seed in the ground and you find anything other than a flower come out, you would be surprised. So, basically, because our art is improvisational in nature, we are called to these situations and then we just produce. Often I will be invited not just alone but with another person, and so we build off of each other, and improvise together, taking into account also the audience and the interaction between performers and audience that is always there. We come up with something.

B.E.: The other night, we saw you perform as part of a much larger group, Nass Makan, or “the people of Makan.” This is a kind of collective band combining different traditions. What is that experience like for you?

S.R.: I actually prefer much simpler performances. Less fusion is better for me. In that concert you saw, I think that the African pentatonic scale won, musically, on the stage. Even though there were very accomplished musicians who are doing different styles of music, I think that the African sun was more powerful.

There is a word called samiyya in Arabic, and it refers to really good listeners. Every performer needs at least a few of them in the audience. Every performance in Arabic music and in African music is unique, because the performers are there, and the audience is unique, and what is produced by the union of those two is always its own thing. So, you have to have these samiyya in the audience, or you are not going to get a high level of performance.

I have been singing for 30 years, and still, whenever I get up on stage, I am scared. I have butterflies. But the more scared I am, the better I perform. Otherwise there is no art. If there is no fear, there's no art.

Makan (The Egyptian Center for Culture and Art)

We saw Jaafra at Makan, which has been presenting intimate concerts of traditional Egyptian music since 2004. Dr. Ahmed al-Maghraby created the venue, and is proud to be helping to develop an educated audience with a genuine interest in the country’s folklore. Amazingly—and Dr. al-Maghraby is not alone in noting this—such an audience barely exists anymore. In our interview at Makan, he explained why.

Ahmed al-Maghraby: It used to be the responsibly the State, the Ministry of Culture, for example, to help this kind of music. In the 50s and 60s in Egypt, the Minister of Culture went to all the villages and created small cultural centers where these kind of poorer guys with the galabeya, peasants, illiterate people, could have a way to express themselves. So that's why today we still have these artists.

In the 70s, we started to live the Sadat moment, where he started to say, "What are you talking about? Fellah or peasant? No, no, no. Let's bring Frank Sinatra and Julio Iglesias." All these big names. Why are you eating traditional food? You should be eating a hamburger. Why you are dressing like a peasant? You should put on Levi bluejeans. And then we started to lose our identity. We started just to imitate the West. Without making an evaluation between the 50s and 60s experience and what they should do next. So it was the beginning in the 70s with this policy of intifah (open door) policy.

And of course with Mubarak, it was a disaster. Really. Imagine 30 years with the same man, and 26 years with the same Minister of Culture. And he was saying in closed sessions that he was proud that he put the intellectuals of the 50s and 60s and 70s in the barn. It was his job to kill any thought, to kill any quality, to kill any difference, any diversity. And just to give to the big lady, or to Mubarak, just an image of a moderate Egypt, an advanced Egypt. And the West had a hand in this process. Because the West helped Mubarak, sustained Mubarak.

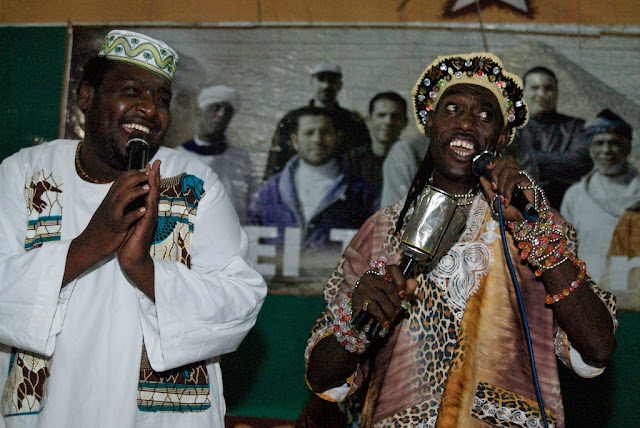

(Ahmed al-Maghraby with Sudanese singer Salma al-Assal and her daughter)

B.E.: Was the idea behind Makan?

A.M.: The idea is to go forward by making a step back to a time when music was a part of the society. When I started to work in traditional music, I found that there was a big gap between how to create music, to do music, to play music, and how to present it. Usually, music is on the stage. You have a wall between audience and musicians. You have the show. So here, we went back to the moment when people come to share music together, not to consume a show. That's why here there is no stage, there is no backstage. You can talk with the musicians. You can see and touch them. You can drink tea outside. And I think it's something that we lost. But it's very precious.

B.E.: What does Makan mean?

A.M.: A place. Just a place. It's not the place, just a place, where people can gather to share a moment together.

B.E.: Every week, you present the music of zar here. Tell us a little bit about this music.

A.M.: Zar is a healing ritual coming from East Africa, and it went into Egypt during the ancient Pharaonic era. Then it mixed with other musical cultures. But in the beginning, it's a healing ritual. It's not exorcism. There is no devil in zar. There are no bad spirits. They believe that there is a parallel world. So there's the human being, and some other spirits. And sometimes there is a conflict between them. So this conflict can make a headache, or problem, or a frustration, or anything. So you go to this healing session, just to express yourself, and you feel music, and you start to move. And you start to end her in the area of people, so you share the energy. And you can find somebody who put his hand on your shoulder to tell you, "Are you feeling good or bad?"

And somebody comes with a cup of tea. And you see this kind of touching, it's very simple, but it's very important. So this is zar according to the tradition. What we do here is not the ritual, but it's the music, and to the sound of this ritual, with the same people, and to the same idea of coming here to share this music. So a lot of people come here, and they enter angry or something like this, and they go out afterwards, relieved and really having a great moment. They put out, put off a lot of their problems.

B.E.: Last week, we saw an actual zar ritual in Boulek Abouleila at the home of Mr. Araby, one of the performers who appears here. In fact, I recognized a number of the artists. The ritual was a very beautiful event. There were families there, people of all ages. It did reach a point of spiritual energy when we were told not to do any filming. People were coming forward with the incense, and the touching as you were describing. It was very powerful. Obviously this is a very old culture, but is felt very alive in Boulek Abouleila. Is this in fact a threatened culture?

A.M.: Yes, of course it is threatened. In the last 15 years, I have seen disappearing a lot of styles, instruments, musicians, know-how, music. Sometimes very quickly. If you talk about the Egyptian music, where is it now? Just a few islands. The Nubian music. Just a few islands. And what I mean about Nubian music, I mean the authentic, and please put that in quotations. Because I don't like “original” or “authentic.” But in reality, you have the media, the TV image of the Nubian. Or the gypsy. Just to sell. And then there is the reality of the Nubians, how they used to do their ceremonies, their weddings. So now it's very hard to go to Nubian and see a real, "authentic" wedding. You will find just the keyboard with the rhythm box and people singing anything from anywhere, with very loud sound. So it's a culture sold by the globalized system. It's just like the publicity of any drink. Can I say Coca-Cola? Or Pepsi?

"If you don't drink Coca-Cola, you are not a human being, so everybody has to drink Coca-Cola and to eat the same hamburger and to go to Kentucky fried chicken or..." It's rising, this globalized TV culture. It's rising, day after day. So in Boulek Abouleila, I hope it will continue, but it's probable that next year you will come here and not find Boulek Abouleila or this kind of people.

B.E.: Here at Makan you are trying to bring this kind of culture to more people, and make this a place of union, and you're fighting a heavy trend, aren’t you?

A.M.: Yes. Fighting a heavy trend, that's one reality. And trying to create a new generation is another issue. It's very hard to convince the new generation to keep these treasures, this legacy. The songs and the daughters of those marvelous ladies, they don't want to continue in that mission. Because the society looks to them as underground, as low class people. It's not the classical music that we should play. It's not the Arabic classical music that you should know. What are you doing? Zar? Wow, it's ugly, it's weird. We have to go to Europe to prove to the European that we have neckties and jackets and dress pants, not the galabeya. That's not trendy. I hope that one day I can find a way to convince this new generation, and to not only the new generation, to find an economic way. Because without economics, you can never create, or re-create something. If you don't have the economy to build something, and to create a surviving exchange, it will die.

B.E.: Right. If you could really provide a way these artists could earn a living, that would be powerful. But playing here must help.

A.M.: It's a part. Just a part. They come here, first of all, to participate in their life. They like to be here. Some of them can earn a lot of money outside, but they like to be here. There are a lot of musicians coming from Pyramids Street, for example. Where they have all the cabarets in the nightclubs, this other world. And they work hard and they earn a lot of money, but they don't like it, because of the ambience. They are just entertaining people. So sometimes, they come here, and earn much less money, but just because they like to play music. It's true that it's a part. But once a week? It's not enough. One festival, a couple of festivals, even four festivals in a year, and this cannot create a family. It has to be something much more solid economically and financially. We want to believe it's just a matter of marketing, with humanism on top. It can be done. There could be a lot of money.

(Zar at Makan)

As another group did with the Musicians of the Nile. And the Sufi musicians, and singers like Ahmed al-Tuni and Yasin al-Tuhami. They met Peter Gabriel. They made business. They made money, both sides. And now, when al-Tuni and al-Tuhami came back to Egypt, and the Egyptian guys they saw the photos and the CDs, and they went, "Ah, this is good. What is Sufi music?" And they started to discover their own Sufi music through a French or an American or British label. So it's just a question of finding the balance between marketing, and especially, a kind of philanthropy a little bit.

B.E.: We went down to Abou Teeg last week to see a moolod. We met Yasin al-Tuhami and heard is son, Mahmoud, singing. It was extraordinary. And clearly it is popular. There were thousands of people there.

A.M.: You are absolutely right. They asked me once, "Who is the most famous singer in Egypt?" Everyone says Amr Diab or Tamer Hosni. Or Hakim. Someone like this. No. The most famous one is somebody like Yasin al-Tuhami. The big best seller until today, is Yasin al-Tuhami. Not Amr Diab. Amr Diab is an image that you see on the TV. But that image sold on the TV can make a lot of money through private concerts, through advertising, through weddings. So if you have the title of being the famous, the biggest, the best singer around, everybody will pay you much more than this Shaykh. But the reality is Yasin al-Tuhami has I think until now 165 albums. He sells like 30 or 40,000 cassettes per month. If any of these big stars just sold 60,000 for one album, it's a big deal for them. Of course in the media, they say that they sold 6 million. It's just a question of how do you sell. They sell themselves.

Sudanese Echoes: Ahmed Sayed Abuamna, Nuba Noor, Rango

Whether at Makan, Tanbura Hall, at a zar, or in other unexpected corners, you find many emanations from Sudan in Egypt. For us one of the most rewarding and amazing experiences of this came at the home of an American percussionist, Miguel Merino, living in Cairo. Miguel is working with a Sudanese musician named Ahmed Sayed Abuamna, who plays the masankop, a relative of the tanbura and other lyres found in Egyptian folkloric music. Abuamna’s pentatonic melodies, shuffling rhythms, and unusual vocal melodies were remarkable, unlike anything we’ve heard. We look forward to forthcoming work by the Otaak Band, the ensemble these artists are creating.

The strongest echo of old Sudanese culture in Egypt is the music and culture of Nubia. This lost African kingdom played a huge role in Pharaonic history, but its physical remnants were mostly drowned under the waters of the Nile, following construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s. Nubia is the folkloric heart of Mohamed Mounir’s vast body of songs, and Mounir calls the construction of that dam and its human aftermath at “the worst project in the 20th Century and the worst migration for a heritage or a group of people.” The Nubian servant became a kind of stock figure in Egyptian films of the mid-20th century. But since the construction of the Aswan High Dam, Nubians have shared a profound sense of loss, and those who perform the music and other arts of this culture feel a huge responsibility to preserve it and pass it on.

That was certainly the case for the members of Nuba Noor, whom we met at Tanbura Hall in downtown Cairo. Tanbura Hall was opened in 2010 by the El Mastaba Center, another young organization dedicated to presenting and developing Egypt’s traditional cultures. We spoke with Osama Abu Bakr of the group about Nubian music and his sense of mission to preserve it.

Osama Abu Bakr: The nostalgia comes from the specific culture around which this music was created. It is very much centered around the Nile, and the physicality of the Nubian landscape, the Nile, the palm trees, their lives as farmers. All of that. I believe that it comes not only from being absent from those places, but also from having the influence of that kind of landscape in the music, and so you find a lot of sadness in it.

Nuba Noor

B.E.: What is Nubian life in Cairo like? Is it just among other Nubian people, or do you come often to places like this to play for a more general audience?

O.A.B.: To answer part of your question, our lives as urban Careans is no different than that of other Caireans, but that there is a specific sector that is related to the music, and the reason that we keep it alive is really the only way we can bring it down to our kids and our grandkids. They are not living in Nubia anymore, and so the only way they can really get a grasp of this history and this culture is if we keep actively alive and pass it along.

Even though some of our audience is Nubian, there are a lot of people who don't belong to that ethnic group come, and even though they don't understand the words, they are taken by the percussion, and they're taken by the music and the dancing and just the entire feel of it. It's something that's unique and a new experience that they don't get anywhere else.

Our main aim is serving Nubian culture, specifically for people of Nubian descent who are living here and who may not have experienced any of these things in real life. So we started with staging some of these life events. Weddings, date harvest, planting season. We performed the types of songs and dances we would do for those. So basically all colors of Nubian life, as a way of preserving and documenting for people who may not have experienced those things.

So, in the same way that the Nubian language, as old as the Pharaonic language, has been passed by generation to generation up until today, we are aiming to do the same thing with Nubian musical culture.

El Mastaba and Tanbura Hall were founded by Zakaria Ibrahim of Port Said. He is also the founder of the Canal Zone folk ensemble El Tanbura, of which more later on. Our Hip Deep Advisor Kristina Nelson said that Mastaba and Makan have similar missions, but also differ in a key way.

Kristina Nelson: What is different about Mastaba from Makan is that Mastaba doesn't just bring the music to new audiences, but it tries to re-integrate the music into its original context. So that, for example, the Sudanese community in Ismailia, that had stopped using its traditional musicians for weddings, now will hire them again. They are re-integrating this music into their daily lives, having lost it, or having given up on it. And I think that's really important. I mean that music is really alive in those communities.

One example of this is Rango, another group specializing in Sudanese-based traditions, including zar, but in the Egyptian context. We met the leader of Rango, Hassan Bergoman, and he told us a little about the group, and the unusual, xylophone-like instrument at its center.

(Hassan Bergoman)

Hassan Bergoman: I am from Ismailia. I'm 60 years old. Both my parents are Sudanese. But they are Sudanese expatriates, who now live in Egypt. I play tanbura, rango and simsimiyya.

B.E.: Rango’s CD is called Bride of the Zar. What is zar?

H.B.: Zar is a sort of freeing of the soul. It is a happy occasion, meant to alleviate the pressure on an individual. If someone is feeling pressured or bothered by something, a zar can help with that. And zars are something inherited, so for example Araby [host of the zar at Boulek Abouleila] comes from a zar family. His mother and his father were both zar practitioners. It’s a tradition that’s passed along through the generations.

B.E.: Tell us about this instrument, the rango.

H.B.: The rango is an instrument that is now pretty much extinct. But I grew up with people who played it, and I learned it back then. Then when Zakaria I got together, we wanted to bring it back to life. So we got a rango from Alexandria from someone who had passed away and left it behind. And I now play that. But it's pretty much extinct otherwise. No one is really playing it.

B.E.: So it is a very old instrument. What do we know about its time and how it was used when it was played more commonly?

H.B.: It used to be really popular, and it was used for all sorts of occasions in Sudanese culture. So it would be at weddings and funerals and things like that. It used to be what is now called a DJ, so at any social occasion, the rango would be played. Now, that is no longer the case. We had to actually remake this instrument so that Zakaria and I could actually bring it to life.

(Rango singers)

Sean Barlow: When you first brought it back, how did people react?

H.B.: The people who were used to hearing it and who I of missed its presence had an immediate positive reaction. But also people who are listening to it for the first time could really appreciate the music, including in our European trips. People of had a very positive reaction to this instrument.

B.E.: Hassan, we understand that the Rango was used in zars. Is that still the case?

H.B.: Because it had gone extinct for a while, and wasn't commonly used, people are no longer requesting it for zars, because they don't really know it as an instrument that used to be part of zar culture. You will see tanbura more often in Sudanese stars. So it's really only practitioners of the Rango who know that it had a place in the zar.

Because it had gone extinct for a while, and wasn't commonly used, people are no longer requesting it for zars, because they don't really know it as an instrument that used to be part of zar culture. You will see tanbura more often in Sudanese stars. So it's really only practitioners of the Rango who know that it had a place in the zar.

Bedouin Jerry Can Band

On another night at Tanbura Hall, we met and heard members of the Bedouin Jerry Can Band, who describe themselves as “a collective of musicians, singers, dancers, story tellers and coffee grinders.” These jocular gents had driven all the way from the Sinai Peninsula—12 hours—to do this gig, and they drove back afterwards. Before their performance, we had a chance to talk with percussionist and singer Ali Ibrahim. Here’s some of what he said.

Ali Ibrahim: We consider Mr.Yahia, our flute player, as our father, because he is an old man and a master. Also there are a lot of players who learned how to play flute from Mr. Yahia. He said that his flute is made from fruit of the desert. The shape is different from one to another, but he says the flute belongs to the Pharaonic era. It's Oriental and Bedouin. And also the flute plays at all the Bedouin occasions, the festivals, feasts, weddings. In the Bedouin Jerry Can Band, we consider the flute the main instrument, along with the Jerry Can.

B.E.: What is the story with this jerry can percussion?

A.I.: Our ancient Bedouin found these Jerrycans in the desert after the war of 1967, our famous war with Israel. Bedouin, in his nature, he love percussion. He can play any something from the kitchen, plates, dishes. He found the jerrycan and he looked at the jerrycan. "What I can do the jerrycan?." He began to play in the front, in the middle, in the bottom. He noticed that there is a distinguished sound that comes from the bottom of this jerrycan. After that, he managed to make it the main percussion in any occasion, and in any group. For us, it’s the jerry can and the ammunition box.

We found a problem we travel through an airport with these jerrycans. The customs always asked, "What's that?" We said, "We are the Bedouin Jerrycan Band. We are a team of folk music, and this is our percussion." Oh, it's impossible. Our manager tried to sort this problem from his country, England, to talk about this problem with everyone there. Even to Egypt Air. Until this time, we still find some problems when we travel with the jerrycan and the ammunition box.

B.E.: Who are the Bedouin?

A.I.: Bedouin are people who live in the desert and take care of sheep. In the winter, when the rain is coming, of course, they stay in the desert to feed their sheeps, to plant some vegetables, something like that. And they have nature in their life. They always go from one place to another, but in the desert, not out of the Sinai. There is a habit I like in the Bedouin. They still go to visit each other one time and another. For example, what is happening in Cairo there? The Bedouin are interested in what is happening, including with the revolution. And they insist that every corrupt minister or prime minister or president has to take his punishment. And our problem with Israel and the Palestinians— for example, when Hamas and Fatah, when Egypt helped them to make forgiveness and to be one nation, as in the past, the Bedouin made a celebration when they heard this news. They always want to hear this news. There is a peace inside them. This is the Bedouin.

B.E.: What about the songs? Are these your songs, or traditional songs?

A.I.: All our songs traditional. For example, when we make training for our group, the same song, we can make another distribution for example, to suggest a different percussion for this part of the song, or a different melody. But the song is old. We can't change the words inside the song.

I think we have to introduce for the audience our songs from our ancient Bedouin. Because there are a lot of groups play guitars, bass, something like that. But when, for example in England, before our concert, there was another group from Mali, Tinariwen. With guitars. Power! After then it was our turn. I can't believe how the audience receives us. “I can't believe it. Just with instruments made of wood and strings, and jerry can. How can it make this great sound? You are fantastic.”

B.E.: Tell us about the poems you sing. How far did they go back, and what do they talk about?

A.I.: It’s old poetry. About old love. Like Romeo and Juliet, but in Bedouin form. We have a storyteller, Mr. Gama, but he is absent today. He is sick. We have this one about Khalif. Khalif is an old Bedouin man, who loves a girl. This girl is the daughter of the old shaykh, from a big tribe. He wants to talk to her father, to take his permission to marry her, but Khalif is a very poor man, but he is a knight, a horseman. He makes a lot of good phrases to manage to meet her to talk to her, but it is difficult. Because his cousin wants to marry her. And he is not a good man. Her cousin marries to catch Khalif and put him into prison.

After a lot of struggles and a lot of wars, the girl’s father says, “We have to judge Khalif. To dismiss him from all of this desert.” But Khalif shouts, "No, your daughter knows me. Please bring her." His beloved girl comes. "No, I don't know this man." He takes off his scarf and begins to say this poem, this poetry. "I am Khalif. I am your beloved man, but what has happened, the excuse your cousin has made of me." She remembers. “This man, I love him, and I insist to marry him." And of course, what has happened makes him believe that this is the real love, the real story, and of course he can't refuse this proposal and make a good wedding. This is one of our Bedouin poems.

El Tanbura of Port Said

We made an excursion to the Canal Zone, to Port Said, to meet Zakaria Ibrahim and hear El Tanbura and Rango perform their regular Wednesday night show at El Negma, a simple, beachside venue, across the Suez canal from Port Said, in the sister city of Port Fouad. The ride takes mere minutes. The show was a spirited affair, despite the fact that Ramadan had begun. The sound system left much to be desired, but the ambiance was terrific, with a gathering of locals singing and dancing along. El Tanbura had 12 guys on stage that night, and the intricate percussion rhythms and melodies of the simsimiyya lyre were entrancing. Various members, including Zakaria, got up to sing. It had the feeling of a social club as much as a band. After the show, we retired to Zakaria’s favorite shisha bar in Port Said, and talked and jammed until sunrise. A night to remember. Here’s some of what Zakaria had to say.

Zakaria Ibrahim: When I started, I was coming from a political background, and all the things I was reading before this were about economics and politics. I didn't know there is something called the science of folklore. When I started to establish El Tanbura, I was doing something very personal. I was looking for something to bring to myself, because I was singing these songs when I was 17, 18 years old. I knew it was going to disappear, and I knew it was rich. I had this idea to do something for this.

Nobody was taking care of traditional music in Egypt, or the Egyptian identity in general. You know, with the effects of globalization, everyone wants to copy the image they are looking at from the West. The West succeeded to make itself as the example, the dream. Why people are dying in the sea, going to die in the sea from Somalia, from Libya, from Tunisia? They are thinking that this is a paradise. And if you go there and see the reality, it is a nightmare. If I go on the other side of the Mediterranean, okay I will be in paradise. And the fact is, they will be a beggar, washing plates in a restaurant, or doing other hard jobs. No paradise at all.

This is because the West succeeded to promote his image as the example, and capitalism is the only way for the human being to continue, and because America is the biggest country, and all this talk, but since it was going not only against the Egyptian identity but against all the poor countries. They are losing their own culture. They can't compete with this mentality. To develop, you have to play guitar and keyboard, and see what jazz music means, and all these things, but not to look to your roots, not to look to your traditions.

(Zakaria Ibrahim)

B.E.: I know the simsimiyya goes way back. I saw a 4000-year-old version of it in the Cairo Museum.

Z.I.: The simsimiyya instrument has been around since Pharaonic time. They called it kinara in this time. You can find it in the Cairo Museum, and you can find it in some paintings in Pharaonic tombs, about 4000 years ago. But also, you can find something in Assyrian civilization in Iraq. It can be older than the documents we have from the Pharaonic times. The documents from Pharaonic times gives us about 2000 years before Christ. And it is for the Assyrian civilization, 2600 years, that other documents are older than this old civilization. But nobody can know now what the melodies were during the Pharaonic times. Nobody can say. There are no records, and nobody has written anything. For this, there is nothing left, and you can't know what kind of music they were doing.

But if we talk about the instrument, you can find it on the two banks of the Red Sea, in Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, in Sudan, Somalia, and also, before in Ethiopia and Djibouti. It was in Zanzibar, in the past. It's finished in Zanzibar now. The main scale for the Red Sea is the Rast scale. One scale, rast scale. And they use it by playing five strings only. These strings don't cover the whole scale. It at least has to be seven, as you know, but they get rid of the highest one end of the lowest one and play the middle of the scale with the five strings.

Anyway, with time, the people in Port Said and Ismailia they started to add new strings. They make seven instead of five. And for this, they have the first chance to play all the scales, all the seven notes. But after, they added more. The strings can be 14 strings, or 21. For this, you can have three octaves, for example. And like this. But anyway, it was just to play one scale at the time. They can't play many scales. Mohssin made this new creation, adding these new strings, in a certain way to be able to play all the scales. For example, the song you heard today from Abu Araby, the oldest singer that you heard tonight. It was part from our repertoire called the Damma songs. Damma songs is something before the appearance of the simsimiyya instrument in the city. And we were singing these songs using percussion only.

(Mohssin Simsimiyya)

B.E: Did you say Mohssin changed the instrument?

Z.I.: Yes. Originally the simsimiyya was made so that it would play only one maqam, one scale, and in the middle of the song, you would have to change from maqam to maqam. There are about nine of them, nine basic maqams that you build on in Arabic music. So you would have to stop each time and retune. The basic maqam is Rast, which is the biggest maqam of them all [like a C. major scale], and the player would have to retune in the middle of the performance if you wanted to play any other maqam. So Mohssin was thinking how he could change it, and then he added that second set of keys that you see at the top, and they corresponds the black keys of the piano. So it makes it harder to play. It is technically more difficult. But he doesn't have to do any retuning during the show, he can play all of the Arabic scales on the same instrument.

B.E.: That's fascinating. And the strings are in two planes. They are separated. So what is the system for which is on which side and which is on the other? As a white keys, black keys?

Z.I.: This one he plays with his left hand. Mohssin had an accident with his finger. He was playing, but when this accident happened, he made practice with his left one to be able to play just with the left one. You can, for example play with two instruments, one here, and one here. For this, he added this new row. It gives him this ability to play with the left hand when he wants to change the scale.

B.E.: What are these Damma songs you mentioned?

Z.I.: This is the traditional repertoire of the songs from Port Said. It is something called Damma songs, which is very old, played with simsimiyya, built here in the city in 1938. This is the first time instrument was built in the city. But for this, and since the beginning of the 20th century, it was others kinds of songs called Damma. Damma is a mix between Sufi songs and the new songs through the gramophone, when the gramophone appeared at the beginning of this century. They started to hear new music, more complicated. And the composers were more professional, using different maqams or scales, and they were singing those songs using just only percussion.

Now, in our time, we can use the simsimiyya instrument, or the kawala, a kind of flute, or the tanbura, which is bigger than simsimiyya, the same shape. But bigger than simsimiyya, and also, the string is not a metal like this, but from nylon.

B.E.: You established Mastaba in 2000, right?

Z.I.: 2000, yes. But before this, there is El Tanbura at the end of ‘88, start of ‘89. Also Waziri group in Ismailia City in 1994. And Hanna group in Suez, also in ‘94. And those three groups are playing a weekly performance, for free, for the local audience, in Ismailia and in Suez. One-time, if you have time and may also, we can make a tour going Monday to Suez to see what is there local musical meeting, and going to Ismailia Tuesday, and come here on Wednesday.

Anyway in 1996, I established this and it became this idea. Because in ‘94, as I said, before, there was a continuous audience for zar music, a specially Sudanese zar, in Port Said. To get tanbura outside of this, and to make it one of our main instruments, and we changed our name to be El Tanbura for this reason. But, after this, I was thinking about how it is my duty to revive zar music. Because it was dying. As you know, it is in some room like this, this is the value of zar, a place like this, like we are here. Not the big stage with a big venue or something. Something like this.

Okay, for this, I established Rango group in ‘96, to make a research, because while I was making a research how I can present zar music in a theater, in a venue, how I can make this transfer from ritual performance to a live performance in the venue. I had to make research. While I was making this research, I was reading a book written by a man called Hadel el Alemi. He was a theater director and also he was a researcher for folk music, and he wrote the book talking about zar, and he mentioned in this book that one of the zar instruments was rango. But he said that it disappeared, and all the instruments disappeared, and all the players died. And he confirmed this information two times in his book, that it is a hopeless case to do anything with rango. It is finished.

B.E.: You proved him wrong by finding that rango in Alexandria. Hassan Bergoman told me about that. I want to ask you about this album called Arwaah. It’s very different from these other CDs El Mastaba has produced by El Tanbura, Rango, and Bedouin Jerry Can Band. Here you are dealing with new compositions, new creations.

Z.I.: This is the result of many years of trying to make some new musical creation, not connected in a direct way with El Tanbura repertoire, but something else, some new music, some new supplemental things to create some new instruments, to discover some instruments also, like rango itself. And we used gandouh also, this little Pharaonic harp. We wanted to bring all this to life, playing and making new music. And we involved some from other groups, from Bedouin Jerry Can Band. In Port Said, here, it was the beginning of building this group, a musical one. And this CD, including combinations of different traditional instruments, and new music, made by the musicians themselves. And also, some traditional songs, but, musically, there is some integration to a new instrument. For example, you can hear a song from upper Egypt playing with rebaba. But you can hear also simsimiyya playing with them, and simsimiyya is very far from Upper Egypt. We didn't play together before. But you could hear this new mix of things like this. For example, Bedouin music, in the traditional songs, there is some new change in the music. These are six new pieces of music, completely new, just music.

(El Tanbura)

B.E.: New creations. New music.

Z.I.: Exactly. And there are six traditional songs, but there is a new arrangement for their music. We are not playing with the same instruments they used to play, but with something else also. So this is contemporary music by traditional Egyptian instruments. And the name is Arwaah, and Arwaah it means spirits. And it means the spirits of all those musicians who participated in the CD from different areas in Egypt. It was a meeting between their music and their spirits, something like this.

And at the same time, it was trying to prove that the traditional instruments can be able to make new creations. I was speaking with a French musician, Lucio, and she was telling me about the string quartet: cello contra bass, viola, violin. This Western idea. I said, “Okay, I can make a simsimiyya quartet, considering the simsimiyya as a violin, and to the tanbura as the viola, and two new sizes of the instrument to the cello tambura and bass tambura.” Something like this.

People have to look to their abilities, what they can do, not only to look to them as something old, and poor, that can't do any new creation or important creation. By building this quartet, and other quartets, with new music, you are somehow chasing the common mentality for those people who are looking to the traditional instruments as something old, and something that doesn't have value.

I think, from the other side, it was this collaboration between the different musicians, hearing each other, knowing each other, I think is developed something in general, not only to keep the traditional musician to play the same music all the time, but also, he can be a composer. He can be anything.