This unlikely Paris-based trio is tearing up the festival and concert stages on both sides of the Atlantic this year. Since we met the band at GlobalFEST in January, they’ve been back twice. Now with their debut album, Mo Jodi, Delgres demonstrates that they are just as compelling on record as live. Bandleader Pascal Danaé traces his roots to Guadaloupe, but his inspiration for this band draws from another musical corner of the Caribbean diaspora: Louisiana. Danaé’s Creole roots come through most strongly in his French-Creole language and the yearning quality of his vocal. But his guitar playing is deeply steeped in swampy, reverb-drenched bayou rock aesthetics.

The album kicks off with “Respecte Nou (Respect Ourselves)” a wakeup call to Danaé’s people that unfolds over a bracing, gutbucket rockabilly groove. With a wild edge in his voice—recorded with metallic vintage aura—Danaé sings, “We’ve been shifting cane, moving wood, raising tobacco, carrying masters, moving rum, handling cotton…” all images that connect his Caribbean and American points of reference. The follow-up, “Mo Jodi (Die Today),” is equally rocking as it hones in on Guadaloupean history. This is the story of Delgres himself, a mixed-race officer under Napoleon Bonaparte charged with restoring slavery in Guadaloupe. Delgres refused, saying he preferred to “die today,” which, of course, he did.

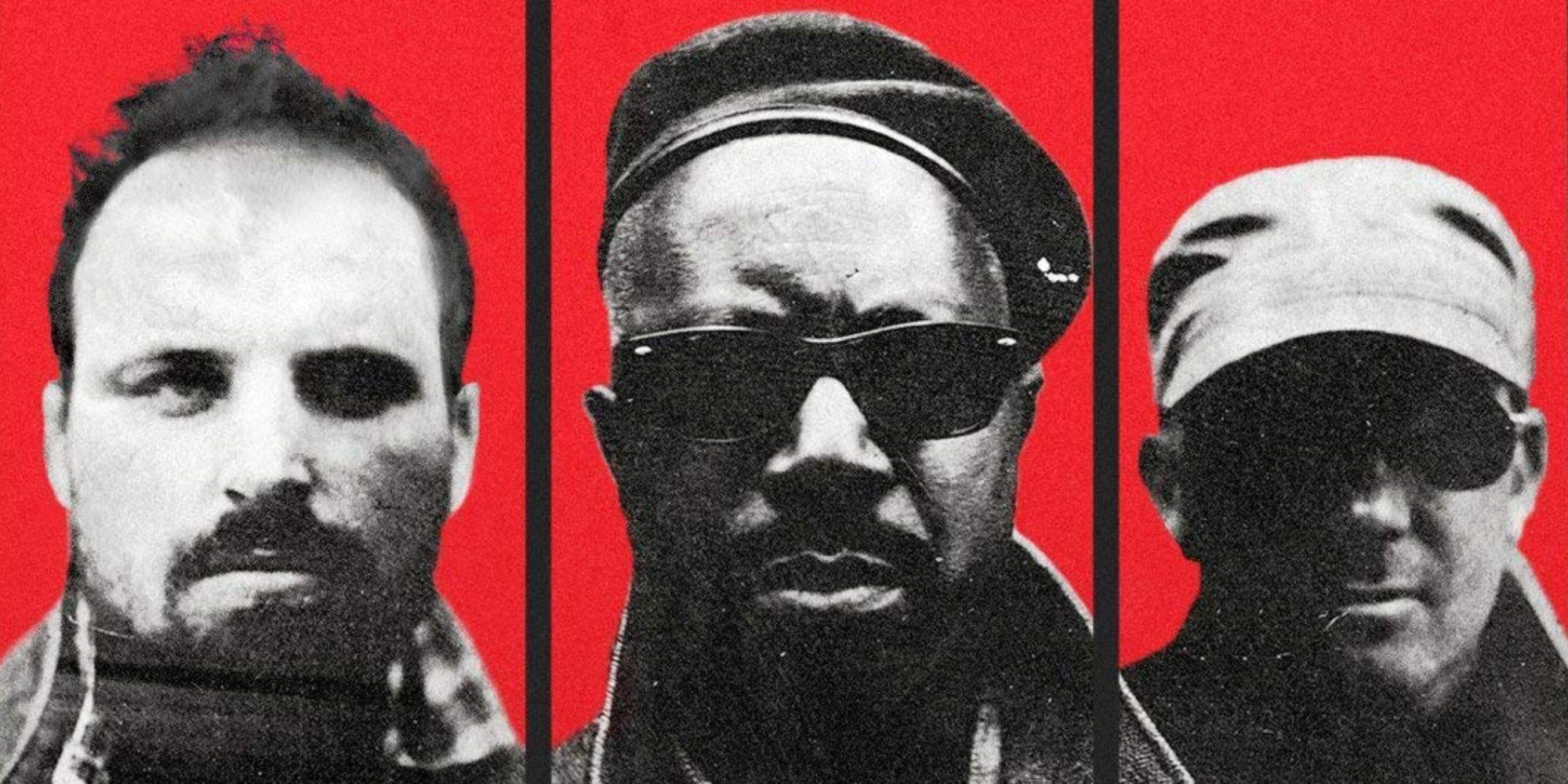

This band has a big sound, especially impressive as it is conjured with just Danaé’s guitars, Baptiste Brondy’s drums and percussion, and Rafgee playing sousaphone bass, and occasional passages of trumpet and flugelhorn. Danaé’s guitar playing is forceful and tasty, whether the mode is stinging electric blues, folksy acoustic strumming (“Pardone Mwen (Forgive Me)”) or soaring pedal-steel, as on “Vivre Sur la Route,” an ambling love song about the trials of life on the road.

The album grows more personal and reflective as it progresses. We hear echoes of Haitian racine music as in Danaé’s crying vocal on “Mr. President.” The song is preceded by a clip from Lyndon Johnson’s 1968 withdrawal from the presidential race, but the Creole lyrics play more as generalized complaint of any poor person under any uncaring president.

There is not a weak song here, and the album coheres beautifully as it moves through moods of defiance and unsentimental melancholy. “Chak Jou Bon Die Fe (Each and Every Day),” a prayer-like acoustic number, has a harmonic progression reminiscent of the Malian griot song, “Kulanjan.” Here, there’s another reference to Napoleon who “wants to put chains around my neck again.” This is a powerful debut from a band that draws on rich and familiar traditions, but renders them with a completely unique, and highly effective, flair.

Related Audio Programs