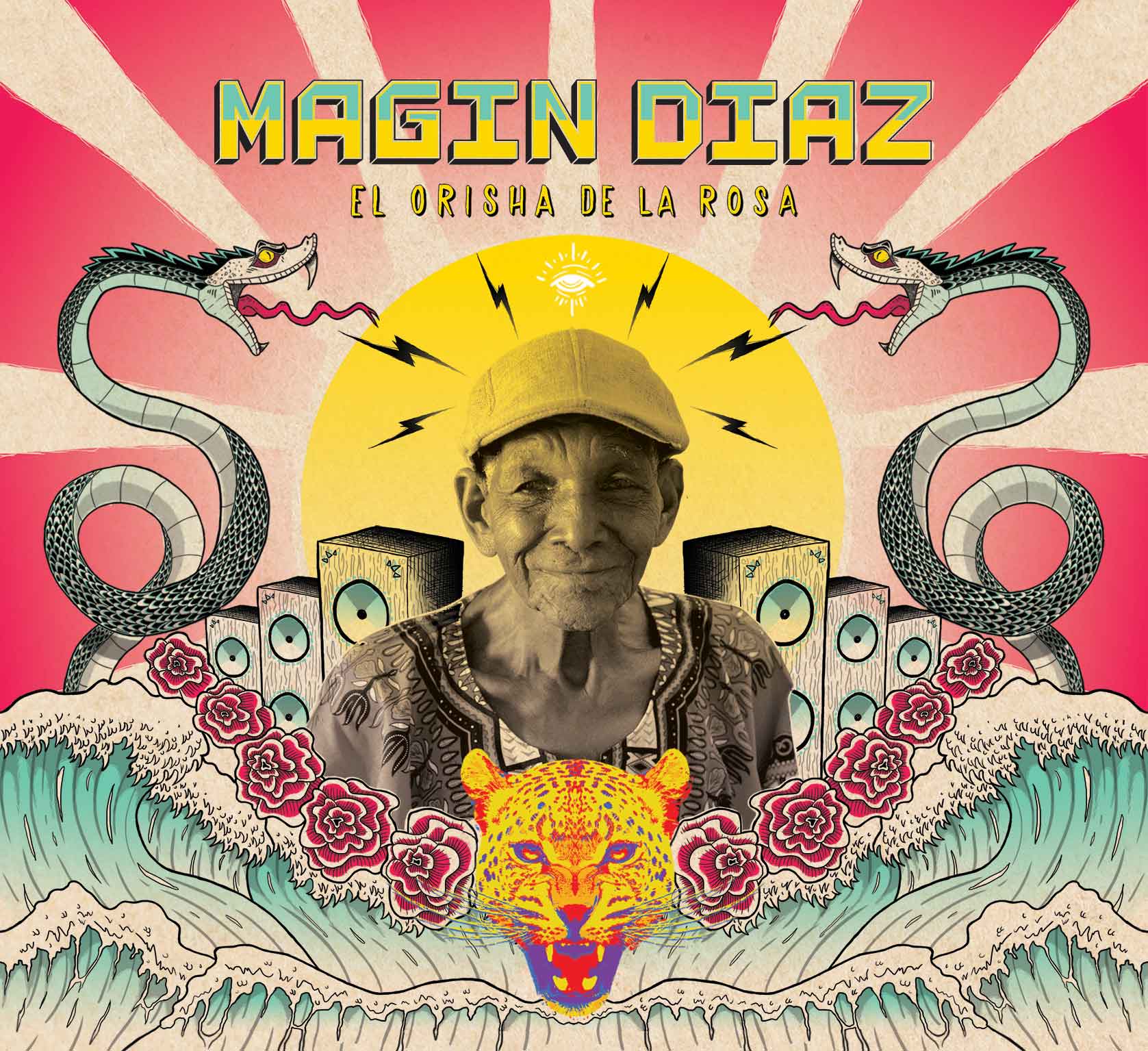

At 95 years old, Magín Díaz recently released his first solo record after a lifetime of influencing the popular and folk musics of Colombia. A legendary traditional singer and composer, Magín's impact on the music of his country has remained largely unrecognized until the release of Magín Díaz, el Orisha de la Rosa on May 23, 2017 on the Noname label.

On top of Magín's truly breathtaking voice and his timeless compositions, the album features iconic artists such as Carlos Vives, Toto la Momposina, Petrona Martinez and Celso Piña in addition to younger, big-name acts like Monsieur Perine and Bomba Estereo's Li Saumet. These musicians not only add to Magín's sound, but also help uncover Magín's story as they sing of his life.

While Magín was relaxing in Bolívar, Colombia in his village of Gamero, I talked with Manuel Garcia Orozco, one of the music producers for Magín Díaz, el Orisha de la Rosa.

Orozco is a Latin Grammy-nominated music producer, composer and ethnomusicologist from Colombia. In addition to his work with Magín, he has also produced internationally acclaimed albums under his label Chaco Music with Petrona Martinez, Carlos Vives, Celso Piña, the Colombian National Symphony, and many more. As a researcher, Orozco has received the Colombian Ministry of Culture’s National Award for Music Research, The Latin Grammy Foundation’s Music Research Grant, and the ASCAP Foundation's Cy Coleman Award. He has written two books in Spanish and has created a digital educational platform entitled Bullerengue Universal, which was included on Afropop's show, "Colombia in NYC."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Eli Berman: Can you tell us who you are and what this project is?

Manuel Garcia-Orozco: My name is Manuel Garcia-Orozco, better known as Chaco, and I produce music from the African diaspora, in Colombia, and the Caribbean. This project, Magín Díaz, el Orisha de la Rosa, is a record of a 95-year-old who has lived anonymously his entire life until recently.

How did you first get involved with this project?

First of all, I produce bullerengue music, and I produce the most prominent artist of the genre, which is Petrona Martinez, who is featured on this album. Through one of her musicians I heard the story of Magín, although I didn’t believe it at the time. Within time, Daniel Bustos, who is the project manager of Magín Díaz, el Orisha de la Rosa, called me to produce the album. The project came to me.

Can you talk about the process behind it and everything that went into the project? Why did it take three years?

When you do these types of projects, the huge obstacle is money. So, it took three years to finance, but at least one year to create it. Magín, what he does is very natural for him. He just sings out his tradition, and then the idea was to preserve and also to create intercultural dialogues with other traditions. The main goal was to give him the recognition he never had before. So, we invited the artists not because they were famous, but because they meant something for the story we wanted to tell.

Did any of them know of Magín before they started working on this project?

Yes, of course! The ones who live in the Caribbean. I’ll name you a few who come from the same tradition and region as Magín: Petrona Martinez, Sexteto Tabalá, Pabla Flores, and Lina Babilonia. [Magín Díaz] is like a neighbor, but for other ones like Totó la Momposina, she probably had a better idea of who he was, but I don’t think they ever met before the project.

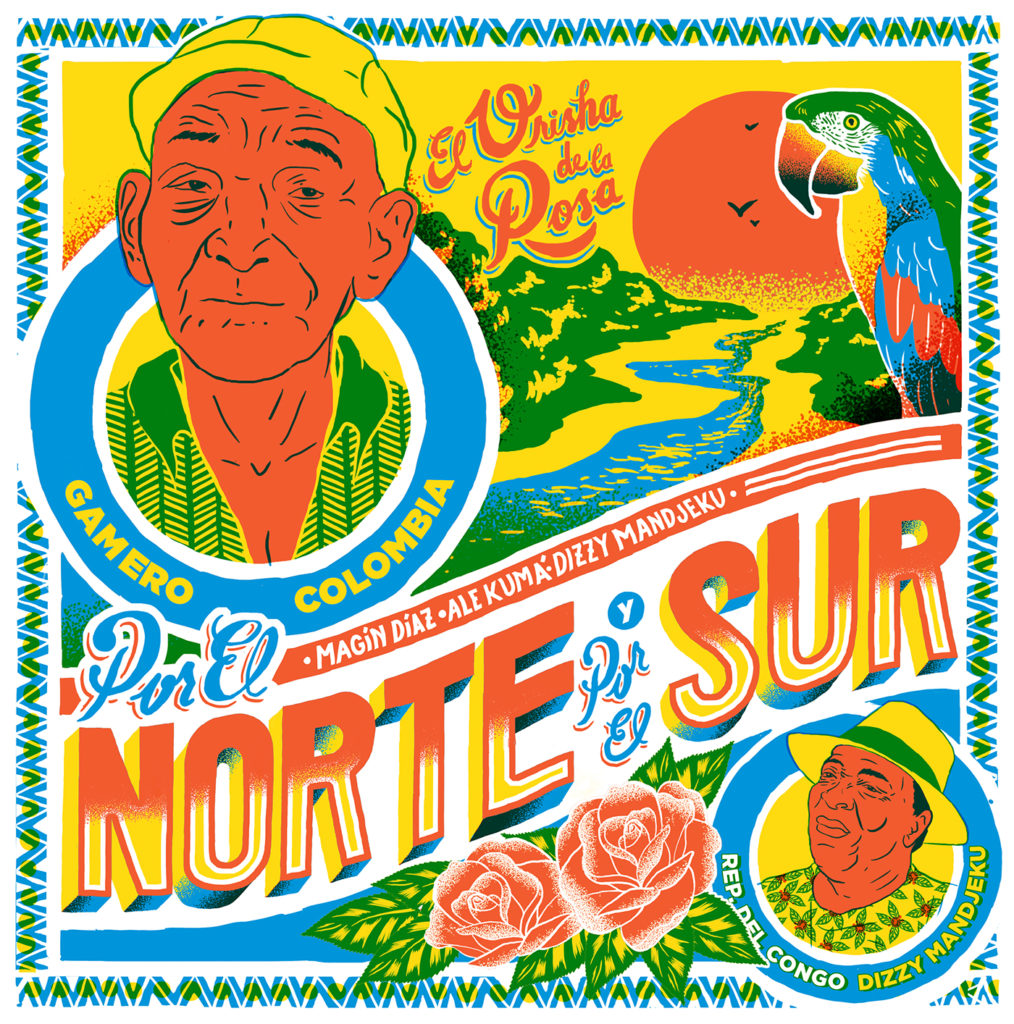

What about these artists coming from other countries?

Every artist came because we wanted to tell a particular story. In the case of Dizzy Mandjeku, who is an artist from the Democratic Republic of Congo—he was touring Colombia at the time, and he was doing stuff with Alé Kumá, who’s another guest on the album, so that came easily. Some other ones like Celso Piña, who’s an ambassador of Mexican cumbia—he has also toured Colombia many times. Colombia is the main source of cumbia, so I think we went to him; he didn’t come to us. Chango Spasiuk, who plays music called chamamé in Argentina—he’s a very respected traditional artist in his country, and he has a TV show on public television in Argentina, and he’s very interested in traditional musics, so we knocked on his door, and he was happy to play with us.

Can you talk about what this story was and what this vision was for extending Magín’s legacy outside of Colombia and outside of his specific region in Colombia?

First, I would like to talk briefly about the story of the genre, because this genre lacks a word in history. The circulation of records is very limited too. Petrona Martinez is the one who has more, and she doesn’t have more than 10 albums, and the other ones have very few—maybe one or two—and very few artists have recorded. So, to understand Magín’s story you have to understand the story of his genre, bullerengue.

Back in colonial times, Africans escaped and populated maroon communities away from the colonists. They kept their drums, had a Creole language, and kept their traditions, and bullerengue is one of them. It was completely invisible to the eyes of the country for centuries. The first recordings of these are field recordings made in the 1960s, never published, made by George List, an ethnomusicologist from Indiana University. You have that time of invisibility, and then in the 1980s a group broke into the recording industry at an original level, and Magín was in that pioneering group. It was called Los Soneros de Gamero. This music was popular in the coastal towns, but decried in the inner cities. It was marginalized music, but at this time at least some people knew of its existence. Then at the end of the 1990s, Petrona Martinez breaks into the world music scene, and then in Colombia people start to ask, “What’s this?” Then she starts touring, and she becomes a national icon. In that story, Magín is still hidden. Then comes a recognition in national identity of bullerengue, and Petrona pioneered that—she got the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Ministry of Culture two years ago. She’s like an icon. Magín was not close to her in terms of friendship, but in terms of region and the type of music. After this record, Magín took the Lifetime Achievement Award, which gives him a nice sum of money, and I hope he doesn’t have to worry for the rest of his years.

With that history, why did you feel it was important to extend that into other countries and into other traditions?

Since Petrona’s breaking into the world music scene, the fact that this music was played first in Europe and then Colombia made Colombian youth look at it with certain respect due to its values of authenticity. There wouldn’t be Bomba Estéreo or even Carlos Vives without these traditions. Although it has never been mainstream, it has always been respected among musicians.

So, the idea was to tell a story—the story of Magín. I heard field recordings of all the songs, chose the ones that I thought were of value to make an album, and we chose the collaborators thinking of what story we can tell from each song. These artists already have audiences, and they already admire this type of music, so it totally made sense to create this dialogue just to get other audiences to find out about Magín.

Can you talk about how the visual art plays into that too?

Oh yes! So, the region has been represented historically as poor, and there’s also a certain word of pity. The image is, in general terms, negative about this region of the country and about this population. But they have a fantastic legacy and music that is amazing, and Magín deserved a better representation of himself. So, we invited people, 18 artists from around the globe, to hear the songs and illustrate them. The result is 18 illustrations that come with the album. The art director, Claudio Roncoli, is from Argentina. He lives in Miami, and he’s a very prestigious artist.

Was he the one choosing or reaching out to different artists, or were you the ones finding the artists?

No, we found the artists. Magín is on social media and all that, but for this genre there’s not a big following. All of it was like, “Hey, this guy is a living legend. Check out this project. Do you feel like it resonates with you?” and most people answered, “Yes, of course!”

Can you describe who these artists were, where you found them, and why you chose them?

I’m the music producer, and I had a lot to do with the music, but with the graphics I didn’t have that much to do. It was mainly Daniel Bustos, who is the project manager, but from the beginning we had this idea. I thought because I’m living in New York, more used to contemporary art, I’d invite people to do installations and crazy stuff, but in Latin America we have a different reality. Some of these people do graffiti. Some others do paintings, collage—collage was the main tool to organize the whole thing. The album is a collage of sounds, and the images are a collage of different artistic techniques.

This idea of collage goes into Magín’s life as well with his ch’ixi identity, right?

Yeah, ch’ixi is a word in Aymara, which sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui uses. She writes about decolonization theory. The way I have translated it in English—people have told me it sounds a little bit offensive. I say “stained,” but people tell me that has a negative connotation in English. What would be a word for when you have a mixture, but you can understand all of the elements of that mixture? That’s what ch’ixi means. In Spanish we translate it as manchado—Sylvia uses that word too—but when I translate it to English, people tell me it sounds weird and even offensive to Afro-descendant populations.

Is it kind of the idea of mixing oil with water where it’s mixed together, but you can see how the two are separate?

Kind of like that. The idea behind Magín’s ch’ixi identity is that he is invisible, but he has been present all these years. He has been present when Carlos Vives packs any stadium around the world. He’s not there, but he’s somehow present. He’s invisible, but he’s a shadow behind all that.

I’m curious about how this relates to the idea that Magín’s history and his truth are not so objective.

His name is surrounded by so many legends and myths, and when I first came to this project I thought they were all true. According to the legend, this guy wrote “Rosa,” which is one of the most popular Colombian songs, but in reality, we find a parallel story in which “Rosa” was recorded in Cuba before he was born. So, that came as a surprise, but it also shows us that this history of the Caribbean is not written and how the Caribbean permeates itself. There was Cuban immigration [to Colombia] with the sugar industry at the beginning of the 20th century, and Magín learned some of their musics as a kid.

All these stories of invisibility encompass a bunch of stories that were never told; that was another thing we wanted to change. The history of Afro-descendant populations in the schools in Colombia is only limited to slavery. This is also about the ch’ixi identity—[African heritage] permeated all the culture. We have many words that come from African words. The music wouldn’t exist without the African heritage, but the history books don’t tell you that. We start with a quote from Manuel Zapata Olivella in the booklet, which says exactly that—“La presencia africana no puede reducirse a un fenómeno marginal de nuestra historia. Su fecundidad inunda todas las arterias y nervios del nuevo hombre americano." [The African presence cannot be reduced to a phenomenon marginal to our history. Its presence floods all arteries and nerves of the new American man.]

That’s so important. It goes back to what Kofi Agawu says about the voice and how integral it is to African musics. Why is the voice so important, especially to Magín? There’s that great quote from Magín that says, "Singing for me is as if someone injected me with life. It's a jolt of new life. If I do not sing, I'd die," and as a vocalist I agree! I know that there’s this super powerful, otherworldly potency to the voice, but I don’t know what it is.

Well, you know, probably since he was in his mother’s uterus, all he knew was music. His mother was a powerful bullerengue singer. Elderly women singing is very important for his culture. This culture is mainly matriarchal, so women have really strong voices and especially elderly women. When they sing you hear them above the drums. That’s as powerful as it is. And Magín right now is 90-something—95 according to his state ID and 96 according to his baptismal record. But, he argues he is who he is and remembers what he remembers through singing. He lived in Venezuela, but he doesn’t give much detail about those years, and he was probably in his 20s, 30s, 40s. But, he does remember a lot from his childhood of hearing those elderly women singing. So, this music was not meant for an audience, but for a community, and singing is crucial for him and for his culture.

This is a type of music that is mostly dominated by women, right?

Yes.

Has Magín ever talked about what that dynamic has been for him being a man?

Yeah, of course! From field recordings, I know that there were male singers before him, and there have come male singers after Magín. This is one of the reasons why he was a secondary part in Los Soneros de Gamero because his cousin, Irene Martinez, was the lead vocalist, and he was a backing singer for her. So, during those years he just had to play the second violin because he was a male. Now that he has aged, and he can sing with that power, he has started to gain some visibility. The oldest video I have seen of him is in 1996 at a bullerengue festival, and the screen reads, “bullerengue group from Gamero, sings Magín Díaz Garcia.” That’s his full name. In that one, songs are not acquired to him; that’s another big issue. Obviously because Irene was on the foreground, she registered all the songs and got that chance.

Even though Magín was writing them?

That’s what the myth says—that he wrote them. We have found three that were already recorded in Cuba when he was a kid or before he was born. With bullerengue, there are songs that are just all over the Caribbean, but there are certain tunes that only one person sings, and those are the ones that people attribute to that particular person. So, in the case of Magín, he inherited a repertoire that says either he composed ["Rosa"], or he is the one preserving it. We don’t know for sure. The legend says he wrote many songs and was never credited, but also, just the word “composer” is a Western concept. So, in the end, for him, I don’t think it mattered, especially when he was young. Now of course with the political recognition and all that he wants to be attributed those sounds.

What does he say about the myths? Does he know if he wrote “Rosa”?

He believes he wrote “Rosa.” That’s his truth, and we give a testimony of that testimony. You have to see how people define themselves. When he sings, the first thing he usually says is “This is Magín Díaz, the son of Felippa García.” As I was telling you, this is a matriarchal culture, so his mother was like the center—“I’m the son of my mother. Here I am. I am singing.” He usually sings a long note, and it is like the powerful statement. So, we’re giving a testimony of that testimony. If he believes he’s the composer of “Rosa,” that’s also how he defines himself. In the record, when he’s playing with Gualajo, he says, “Hey, this is Magín Díaz, the man who loves Rosa.” The story is that as a kid, a white girl rejected him, and he wrote the song. So, he took that story, of which only he is present, and there are no witnesses, and he self-historicizes himself.

Are there other instances or stories about him self-historicizing?

Well, the only fact that he doesn’t know—how old is he, and when was he born—says a lot about what people at the time knew about the region. Some people believe that he is older than 100 years old, and I don’t believe that that’s exactly true. His baptismal record is when he was five or six years old, but from the signatures, from the documents, we know that his mother, father and grandmother were present, so it’s whatever they recalled. But, that fact that he didn’t think of that date as his birthday says a lot. So, that’s a myth that he’s older than 100 years old. If you ask him how old he is today, he may tell you 96, and maybe tomorrow he tells you 97, and he doesn’t know for sure.

Another myth is that he wrote songs that were stolen. I just give him the reason, you know, that’s what he says. For the ones I found evidence that it’s not true, I tell on the booklet, either way he’s the one who preserved them and sang them anonymously for so many years. Another big myth is that he played with Los Billos Caracas Boys, which was a huge recording success from Venezuela, but from listening to the recordings—by the way, we have a huge archive of these recordings online on his website. We have field recordings and interviews, and I restored all of those—but after listening to all the interviews, what I came with was that he once jammed with them. That’s what his cousin says. Then the myth was aggrandized. He probably jammed with them, knew them. They were probably impressed with his voice, but from what we know, he was a party man and not a disciplined singer. That’s why his career was not very—let’s say “successful” in Western terms.

So he always had a great voice, but he was just never trained?

They all are empirical. All bullerengue singers never studied, and they know their tradition, which is linked to their African heritage. The way he breathes, and the way he keeps those long notes, and his pitch is great—you have to understand that this music doesn’t have harmony. You find the guitar in most traditions of Latin America, but not in here. The Spaniards did not influence this region very much. Other than the language and some Catholic elements, I don’t see their influence.

I just think it’s amazing how he sounds at 95 or 96. He sounds like he’s 30. You were saying that it’s older women and older people in general that have these powerful voices. Is this a power that comes with age, or is it something that is sustained?

The youngest I’ve heard him is on a record by Los Wadyngos in which he sings lead—on [Los Seneros de Gemero] he sings lead for like three seconds—but from what I can tell his voice has lowered a bit, and the cultural memory is so strong that Magín says he’s sung his entire life, but for other bullerengueras, traditional bullerengue singers, I’ve heard that they never sung until they were elderly. So, somehow they replicate the lives of their ancestors. I don’t think they do it on purpose, like consciously a 20-year-old thinking, “Oh, I’m going to sing when I’m 60.” It is just something that’s in the culture; it comes in a very strange way.

Is there anything else you’d like to add about the project?

The main goal of all of this was to improve the quality of Magín’s life, and we probably achieved that. His life pension has increased. The Colombian Ministry of Culture gave him the Lifetime Achievement Award, which is a good amount of money. I don’t think he has to worry for several years. Let’s see how many more years he still has. Hopefully many, many, many more.

We won some political territories that were important for the project, like a preservation grant from the Latin Grammy foundation. So, we put all the archives on the Web. Daniel presented a paper about Magín Díaz at Harvard University. Things like that, that although don’t mean money for Magín, mean political recognition from which we can gain resources for him. That last time I saw him was when we released this, and he was at the press conference. I saw him in very good spirit. He cries whenever he hears the album, and I’m so glad because that’s beyond words and beyond all the effort we put in to make this album a reality.

Awesome. That is so cool.

Thank you so much for this interview.

Thank you so much for coming, and thank you for making this art.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

You can download and stream Magín Díaz, el Orisha de la Rosa here, but I highly recommend purchasing the physical album in order to experience the stunning visual art and extensive research that is included inside.