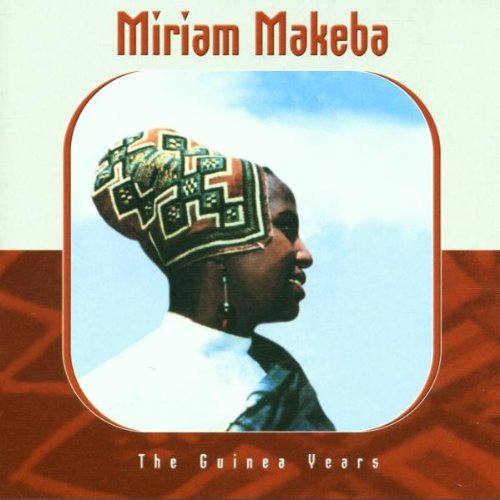

An appreciation of the life and work of the immortal Miriam Makeba, universally known as Mama Africa, from Ken Braun of Sterns Music on the occasion of the 85th anniversary of her birth: March 4, 1932. The piece recounts the little-known story of Makeba's sojourn (effectively political exile) in Guinea during her marriage to the controversial civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. The original version of this account appeared in the liner notes of Sterns' release of Miriam Makeba: The Guinea Years and has been lightly edited for style.

One morning 15 years ago I got a phone call at my office in New York from my boss at the Sterns African Record Centre in London. “We have a visitor here who would like to say hello to you,” he told me. Before I could ask “Who?” I heard a soft laugh and a mellifluous voice slowly enunciating “Well, I would like to say more than hello.” I recognized the voice immediately though I’d never met the person it belonged to. “Miriam Makeba! What a delightful surprise!” “Oh, I am delighted, too,” she said, “because I read what you wrote about me for our album and I wanted to thank you. You tell the truth so nicely!” She was referring to The Guinea Years, a selection of recordings she made in Conakry, Guinea, between 1968 and 1978, which Sterns had recently released with a short bio I had written. The text focuses, reasonably, on the period she lived in Guinea, but it also touches, necessarily, on her life in South Africa and the United States, and I think it holds up fairly well as a brief overview of her extraordinary career.

What’s missing, of course, are the last years of her life. She continued to travel the world to lend her support and her voice to good causes. At the age of 76 she suffered a heart attack on stage at a concert in Italy to raise funds for the protection of a young journalist whom the Naples Mafia had vowed to kill for exposing its crimes. She died that evening. The journalist is still alive. Today is Miriam Makeba's 85th birthday. More than a quarter-century before the term "world music" caught on, Miriam Makeba was a world music star. She had been a popular singer and actress in Johannesburg since 1953, but beyond South Africa and neighboring countries she was unknown. That changed dramatically when she landed in New York on Nov. 30, 1959. Within a few dizzying weeks of her arrival in the United States, she had appeared nationwide on prime-time live television, recorded the first of her six albums for RCA, and begun preparing for a concert tour with Harry Belafonte (a huge star at the time).

Her fame spread rapidly to Europe and around the globe. A show-business success, a media darling, a fashion plate, an award-winner, she was an international pop star—the first from Africa. Makeba introduced African music to millions of non-Africans. She sang songs from South Africa's Zulu, Sotho, Swazi and her own Xhosa folk repertoires along with new songs from the multi-ethnic urban townships. She also sang songs from other regions of Africa, and her albums and concerts included songs from every other continent on the planet – folk songs, standards and new compositions. She spoke half a dozen languages and sang in many more. Touring far and wide, she brought audiences an unprecedented breadth of music and also gave them back some of their own in her unforgettable voice. She could follow diverse traditions faithfully or rework material in new ways. Along with Harry Belafonte, Pete Seeger, Antonio Carlos Jobim and a few other artists prominent in the late '50s and early '60s, Miriam Makeba invented a genre – a sensibility more than a sound – which could aptly be called world music (though it had no name at the time). It was music with a world view and worldwide appeal.

Stephen Biko once said that every South African was involved in politics. Makeba certainly was, but not by choice. During her first year and a half in the U.S. she was reluctant to comment on South Africa's brutal legalized racism, but after the Sharpeville massacre of 1961, in which several of her relatives were among the 69 civilians killed by the police, she couldn't keep herself from speaking out. Newspapers quoted her. The South African consulate in New York retaliated by revoking her passport when she wanted to fly back to Johannesburg for her mother's funeral. She was no longer a citizen of the country of her birth. Then, when she addressed the United Nations' Special Committee on Apartheid, the government of South Africa "banned" her. Thus she became, in effect, a criminal at large, subject to arrest if she returned home. But to people of every color and nationality Makeba was a heroine. Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy both heard her sing and expressed their admiration for her. So did many heads of state and a good many of their opponents (openly or in secret). She was seen as an icon of civil rights, ethnic pride, self-determination and internationalism. "I have become a world citizen" she remarked, and in fact she nearly was one: In that period she traveled on diplomatic passports issued to her by eight different governments.

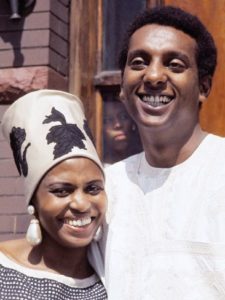

A music festival brought Makeba to Guinea tor the first time in 1967. On that occasion President Sékou Touré, who had led this West African nation to independence from France nine years earlier, presented her with a signed copy of one of his books and invited her to come back and live in Guinea. Leave the country that had first welcomed her when her native country had refused her? Many Americans loved her but others distrusted her, even hated her, particularly when she took up with Stokely Carmichael. They were suspicious of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (however innocent the name sounded) and they saw Carmichael, its leader, as a dangerous radical. The FBI tailed him. When he married Makeba in 1968, the FBI included her in its "investigation." Suddenly, and inexplicably, her American concert engagements were being canceled and her record company dropped plans to make a new album. Only a few months before, she'd been in the Top 20 with "Pata Pata," and two years earlier she'd won a Grammy (the first awarded to an African); now she couldn't get a gig. When King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, the FBI charged Carmichael with inciting the riots that broke out in Washington. Things very quickly got very shaky for Carmichael and Makeba. They fled to Conakry, Guinea.

Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba on their wedding day.

President Touré welcomed the couple to Guinea with open arms, declared them permanent guests of the state and gave them a villa. Guinea would be their home. The nation was celebrating the 10th anniversary of its independence, and revolutionary zeal was still the order of the day. Touré called his ideology African Socialism, and zeal was an essential component (as grand plans far outnumbered successful programs). There's every reason to believe that Sékou Touré genuinely admired both Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba, but it's also clear that he used them. The famous newlyweds enhanced his prestige, and he took them with him on travels throughout the country and abroad. The president made each a special ambassador, and each filled his or her role well. Carmichael held strong convictions, possessed a keen intellect, and could speak compellingly to heads of state and crowds on the street alike. Makeba overcame her natural shyness and applied her sympathies, talents and star power to good works in remote corners of Guinea and at OAU and U.N. conferences in foreign capitals. Yes, Touré used Carmichael and Makeba, but they gladly allowed themselves to be used and never doubted that their causes were just.

Sékou Touré was an autocrat who brooked no opposition. Regarding music, however, he showed an open mind and good judgment. Early in his presidency he had established a national network of music schools, festivals and state-subsidized ensembles. By the time Miriam Makeba arrived in Guinea, he had built a recording studio in Conakry and founded a national record company. His charge to musicians was twofold: honor Guinea's great classical and folk traditions (which colonialists had disdained), and create modern African music. This was one program that did succeed – gloriously. Touré's support enabled traditional singers, drummers, dancers and the country's virtuosic players of the kora and the bala xylophone to devote themselves to their art. Guinea's splendid modern bands could not have made the records or mounted the tours they did without their government's sponsorship. So Makeba encountered a flourishing musical environment in Guinea. It didn't need the gilding of an international star, but it made room for her. And though she didn't need Sékou Touré's patronage to further her musical career (she could get all the work she wanted in Europe), she eagerly accepted it for the opportunity to take part in a renaissance. She assembled a formidable group of Guinean musicians, learned old and new songs in the Maninka and Fula languages, toured with Les Ballets Africaines de Guinée, promoted younger singers such as Sona Diabaté, and recorded exclusively for Syliphone, the Guinean national record company.

Miriam Makeba recorded at least 28 songs in Conakry. Eight of these, plus four more written and sung by her daughter, Bongi Makeba Lee, were included in a Syliphone LP entitled Miriam & Bongi. A second LP, Appel á l'Afrique, featuring Makeba with a Guinean quintet, was recorded live at the Palais du Peuple in Conakry. Both LPs (or abridged editions of them) have been available intermittently outside of Guinea. Only an abridged version of the live LP has been released on CD. But Syliphone released other Makeba recordings in Guinea only. A number of 45 rpm singles have been gathering dust in the Syliphone archives in Conakry. Six of these recordings are presented together for the first time in The Guinea Years. This revelatory new CD also features two songs from the Palais du Peuple concert that were never included in international editions of Appel á l'Afrique. Rounding out this unique compilation are seven cuts from Miriam & Bongi, an LP that has long been out of print. This album presents Makeba in her ever-remarkable multilingual mode, singing in six African languages, two European languages, and Arabic. The music is correspondingly varied. Three songs have been in her repertoire since the earliest years of her career in South Africa: two by her Zimbabwean friend Dorothy Masuka, and "Lovely Lies," which she first recorded as “Laku Tshoni Llanga" with the Manhattan Brothers in 1954. Her own composition, "Amampondo," is based on a Xhosa rhythm. "West Wind Unification," which her daughter Bongi wrote for her, sounds like early '70s soft soul music – which it is. "Jeux Interdits (Forbidden Games)" is a contemporary French chanson. "Milélé" is a Congolese mother's lament for her dead child. Perhaps the most unusual piece of this collection is "Africa (Ifrika)," by Algerian songwriter Lamine Bechuchi, which combines Manding-styled electric guitars with Maghreb-styled violins.

For many listeners the most interesting of these recordings are bound to be those that are most Guinean. "Two," "Ojuiginira" and "Malouyame," are classics of the Manding jaliya canon of praise songs. "Ojuiginira" recounts the virtues of Sékou Touré's great-uncle, Kémé Burama, and "Malouyame," also known as "Bani," could be – and usually was – interpreted as a tribute to President Touré. Two other songs, also of traditional origin, "Touré Barika" ("Thanks to Touré") and "Sékou Famaké" ("Sékou the Mighty Ruler"), are obviously addressed to the man who bore those names. "Maobhe Guinée," a song in the Fula language, is somewhat more general: It lauds the president's entire Parti Democratique de Guinée. Miriam Makeba was no sycophant. While she had much to be grateful to Sékou Touré for, she was only doing what all musicians in Guinea did in that era. Even the Malian singer Salif Keita sang Touré's praises in "Mandjou." Praising leaders is an ancient custom that is still practiced in many parts of Africa, particularly in the West African countries where griot traditions remain strong. Moreover, for Makeba, these songs integrated her political and her artistic ideals. The politics may seem naive now, but the art remains unassailable, for what is most striking about Makeba's Guinean songs is how adeptly she sang them. To hear this woman from a Johannesburg township sounding like a jelimuso from Kankan is to realize that Makeba could sing just about anything with aplomb and soul.

In 1978, when Makeba was 46, she divorced Carmichael after 10 years of marriage. By that time the Guinean economy was failing badly and President Touré's rule was becoming increasingly repressive. Makeba quietly resigned her commission as a U.N. delegate, but she continued to live in Guinea (as did Carmichael). She gave an occasional concert but recorded nothing more for Syliphone, which was on its last legs, one of the many enterprises felled by the country's declining fortunes. Makeba spent most of her time in the remote village of Dalaba, where she had a modest house. Her daughter and grandchildren often stayed with her, and she involved herself in village projects and community health. In 1984 Sekou Touré died. His designated successor was soon ousted by a coup d'état, but though the new government was critical of Makeba's ties to the Touré regime, it allowed her to stay in Guinea, and she accepted. And she never stopped singing. In 1987 she joined Paul Simon and her countrymen Hugh Masekela and Ladysmith Black Mambazo on a historic worldwide tour, and the following year she recorded an album in New York – the first she'd made there in 20 years. Then in 1990, when apartheid authorities in South Africa finally released Nelson Mandela from prison, they also lifted the ban on Miriam Makeba, and she returned home after 30 years in exile. Four years later, as millions of people around the world listened by radio or watched on television, Makeba sang at Mandela's inauguration as South Africa's first democratically elected president. Miriam Makeba will turn 70 years old in 2002. She still sings for devoted audiences throughout Africa and every other continent on our planet. She is, after all, truly a world music star (stress each word: world... music... star), and she always will be.

Read more about Miriam Makeba from "Best of The Beat on Afropop."