Martin Scherzinger is a media theorist and professor of mathematics at New York University, but he also plays the Shona instrument, mbira dzavuzimu. In an article for Perspectives on New Music entitled “Negotiating the Music-Theory/African-Music Nexus,” he uses Western music theory to analyze Shona mbira music. Scherzinger finds surprising “fractal-like” mathematical relationships hidden within the song, "Nyamaropa," and other major mbira tunes. He thinks these characteristics of Shona mbira music--when taken together with the instrument’s unique design and performance style--make mbira music the ideal soundtrack to accompany Shona spirit mediums into trance states during bira spirit possession ceremonies. Producer Brendan Baker interviewed Professor Scherzinger as part of his research for the Hip Deep program "The Nature of Trance."

Brendan Baker: You’ve mentioned that the actual design of the mbira dzavuzimu has a huge impact on the music performed during Shona spirit possession ceremonies. How so?

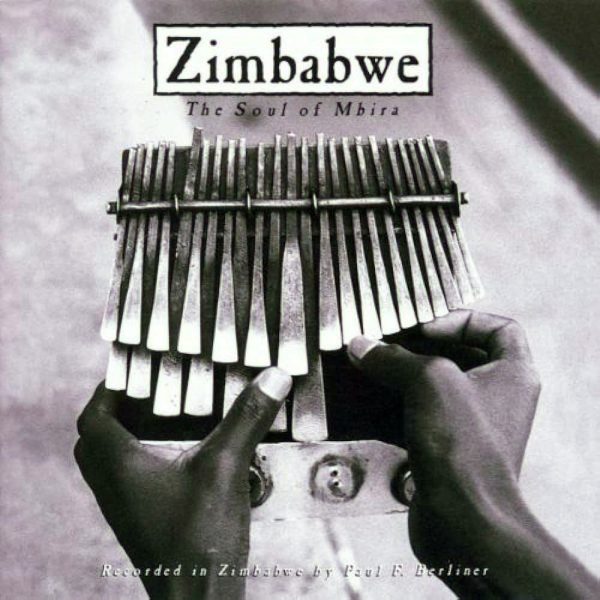

Martin Scherzinger: The mbira is, broadly speaking, a musical instrument that is comprised of pieces of metal that emerge from a soundboard. There are also bottle caps or shells attached to the instrument that create a sort of buzzing sound along with these vibrating metal tongues. The interesting thing from a perspective of the West (in terms of the way it interfaces with the human body) is that—unlike the piano or other Western instruments—the low and the high notes are not opposed as a kind of “left” and “right.” So in the case of the piano, the low notes are off to the left, the high notes are off to the right. Here [on the mbira dzavuzimu], the low notes are in the middle and they fan out with higher notes off to the ends. The symmetrical structure more or less matches the kind of ergonomics of the playing hand. So the thumbs are in the center and the four fingers are off to the side. Interestingly, it is also left-hand centric. The left-hand thumb (which is considered in the West to be the weakest and clumsiest of the human digits) turns out to be the most active.

The second important point is that no sound is struck in its bell-like purity because of these vibrating and buzzing sounds (the bottle caps, the snail shells and so on). This puts a kind of veil on the music-- think of a snare drum--that hides the music and entices the ear into a closer proximity to the music. It is as if the pitches and the rhythms are a little bit hidden from the ear, forcing the ear to move closer into the music. If you watch mbira players they often have their heads deeply buried in the instruments as if to seek out something that isn't quite there. I think this is important because mbira players frequently report that what they play is coming back in a form that isn't quite the same as what they are putting in. The music seems to answer back to them in a way that is not the match of what they're doing.

The third thing that matters here is the way the tones on the mbira have extremely prominent overtones. Which means that every time you strike a low note, it is multi-pitched in a very prominent way; you can hear a very high-level pitch that intersects with the higher levels of the music. It's as if there's a sort of “second line” that appears. And if you look at testimony by mbira players such as Hakurotwi Mude, he actually will often use the metaphor of “high vocalization” or the mbira seems to “sing back, revealing sound like a flute.” "When the mbira sounds like a flute," he says, "the ancestors come."

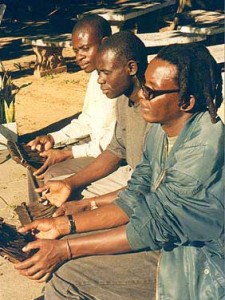

Another aspect--which I think is the most important and not much spoken about--is the division of labor between two players in relation to the musical whole. When one player plays a series of notes, the other player places his series of notes within the spaces of the first player. The one interlocks with the other throughout. So no player is responsible for a single musical line; the emerging pattern between the two--the interweaving of the two--is the important outcome, as far as the ear is concerned. This is very important because in some sense there is now a mismatch between the motor image and the sounding image. There's a way in which the two are misaligned.

The “motor image” being what the performer is seeing as he or she is playing?

Yes, indeed. And the way in which their entire body moves in relation to a rhythm and so on. In other words, when you play a certain a pattern, whether it's in 3/4 time or compound time (a 6/8 or 12/8 and so on) or any other temporal span, you will invest that pattern with qualities that will give it a certain shape through tiny inflections of motor patterning. It's hard to describe in the abstract, but it's very hearable in terms of the phrasing and the small incremental accentuation of patterns that are built in whatever line you're playing.

And each of the performers hear their own patterns in different ways by way of radical interlocking; one is always playing one pulse off. And as a result, rhythmic melodic lines emerge that are at the very least a mismatch to the kind of bodily actions that produce those patterns. In other words, the meter and the rhythm heard by the ear is very different to the meter and the rhythm that is produced and felt by the player. As a result, these ephemeral, almost uncanny patterns emerge when they are taken as a unified gestalt.

And how does it feel to be a performer playing this music and to have these parts emerge? Are you conscious of each of those emergent patterns as an mbira performer?

That's an interesting thing. Once you get really good and the performers are really developed, you start to shuttle between different modes of hearing. And the experience for your ear is very, very different from the motor patterns that you're producing. And yet you want to keep changing and improvising new patterns that may emerge. So [when listening and playing simultaneously] one has to sort of “keep one’s cool” and oscillate between the one and the other in a careful way, always being vigilant about what's going on in the whole.

It's a music of incredible intensity. It’s not that difficult to perform a single line. The virtuosity comes in at a much more understated level when it's put together with another player and one needs to improvise in a way that produces beautiful, unguessed-at melodies.

What makes for “good” playing or effective playing?

It is a conjugation of things. I do think it is extremely important that the player is able to hear what is happening in the totality, while at the same time keeping a very consistent sort of focus on this “alternative universe”--that is, the universe of his body producing certain kinds of sounds. And I think that disparity requires a particular kind of virtuosity. I don't think it has anything to do with speed or repetition. On the contrary, I don't think the music repeats at all. I think it is constantly kaleidophonic. It tricks the ear. It gives you an experience of a transformation through repetition. Or a very good way of putting it would be to say, this is transformation posing as repetition. And it's precisely that it poses as one thing and becomes something else that it issues forth its ability to transport you out of the everyday.

You also have a theory about the harmonic structure of many of these songs. Can you tell me about the song, "Nyamaropa"?

Yeah, if you took a song like "Nyamaropa" and you analyze it in terms of Western metrics--you simply break it down into harmonic progressions--you'd have approximately 12 chords that follow each other in a sequence, and then repeat themselves in a circle.

But if you turn that progression upside down and ran it in reverse--in other words if you notated the chord progression on staff paper and then you turned that staff paper upside down and then read it back to front--you would have exactly the same progression. In the West, that's called retrograde inversion. (It doesn't have a name in Zimbabwe as far as I know, but it has a consistency from one pattern to the next.)

It doesn't only retrograde invert around itself. If you went to he middle of the progression and ran a kind of intervallic analysis both to the left and to the right of this music, you would again get an “intervallic palindrome” that runs precisely at the music in reverse again. So there are many ways these time-transcending symmetries and asymmetries of the music trick the ear into thinking it is one thing, as it becomes another thing.

And if you took that 12-chord progression [from "Nyamaropa"] and you started a similar progression from the middle of that chord progression from the seventh chord, and you ran it backwards by skipping every second chord--if you ran that progression backwards by skipping every second chord as a kind of interlocking sequence, and you spread that around the circle twice, you would find that you get again an identical progression this time running backward at half the speed. One might call this a retrograde augmentation of the initial pattern.

This helix-like weaving of multiple harmonic progressions into a single progression is a real characteristic of this music. And I've looked at various “big tunes,” and they all have this sort of characteristic. Now we may just think it's a coincidence or we may want to take it seriously and say, there’s this fractal-like logic where there's a recursion on a different time scale of the same progressions. It creates a kind of audio conundrum, because the ear can follow various trajectories at the same time. And if you follow every second chord, you will eventually find yourself hearing the same music at a slower speed. This kind of thing--these wheels-within-wheels--I think, are part of the experience of generating spirits or bringing about something profoundly different within the same experience. That phantom pattern again. Some sort of “conundrum for the ear.”

Do you think these sort of musical qualities help bring on spirit possession during Shona bira ceremonies?

For most mbira players, the music is far from merely a sensuous experience. It is central to a spiritual cosmology. It speaks back to the performers in ways that exceed their input. And the ability of the music to do that for various technical reasons--to elicit these audio conundrums, asynchronous sounds, melodies that appear as phantoms, and so on--all of this, I think, allows the listener, the ear, the actual sensory apparatus, to go beyond the dimensions of the tactile performance alone and touch upon something unguessed at.

But I’m trying to find out some of the sort of technical reasons why that happens. Why the ear, when it is tricked in this way, may sort of discover something radically different within the same thing. And I think when that happens, the intensity of that, the mystery of that has the ability to prompt the mystery of the universe. It’s not enough to say what I've said, but as a secular person I wouldn’t want to romanticize anything beyond that. I have deep respect for mystery of magic, even if magic is an excessive use of technique.

Related Audio Programs