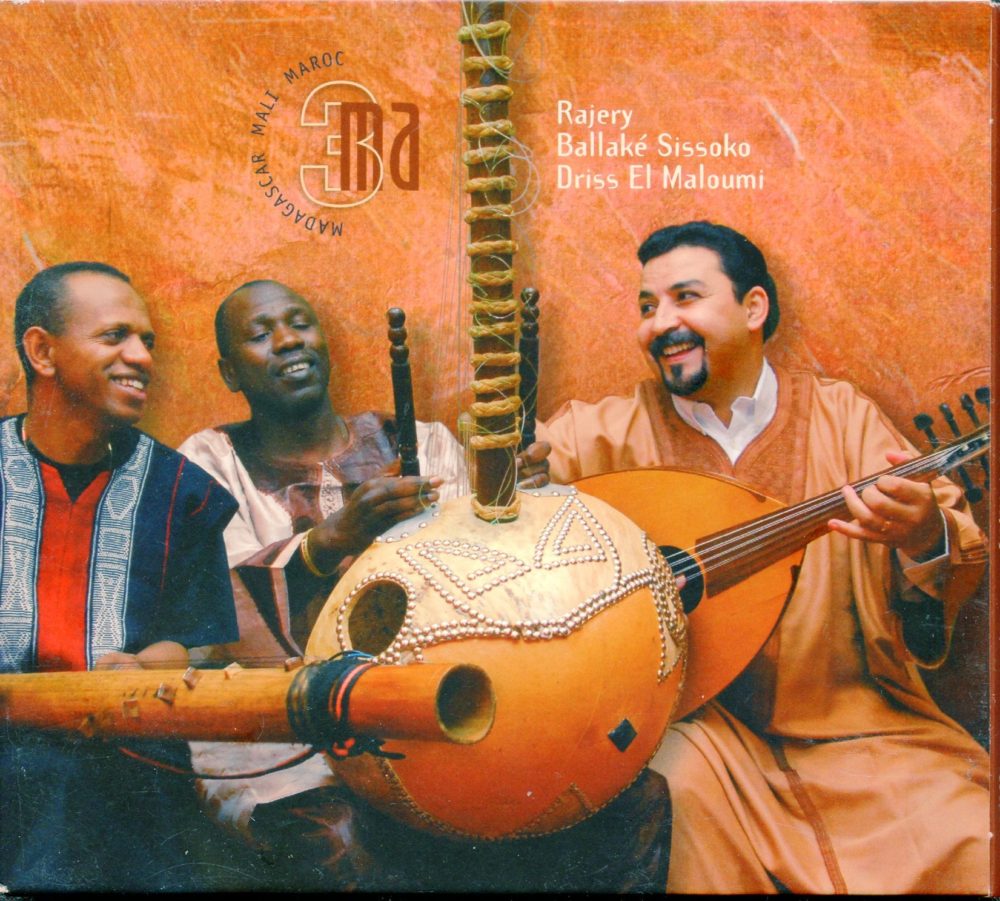

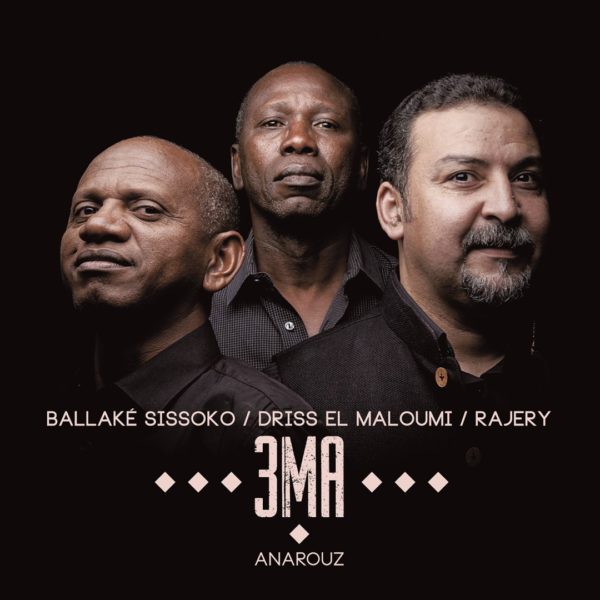

3MA is an unusual trio of string instrumentalists from three countries that—in French anyway—all start with the letters M and A: Mali, Madagascar and Maroc. Ballaké Sissoko of Mali plays kora, Rajery of Madagascar plays the valiha tube zither and Driss El Maloumi of Morocco plays the oud. This project could have passed by as a collaborative novelty, producing a single album in 2008 simply called 3MA (Contre Jour).

But it didn’t stop there. Almost 10 years and many concerts later, there was a second album, Anarouz (Mad Minute Music, 2017). That year, the trio also participated in Jordi Savall’s extraordinary touring show, The Routes of Slavery. On Feb, 1, 2020, the trio made their proper New York debut at Public Record in Brooklyn, a beautiful, woody room with a superb sound system and gorgeous acoustics. The concert was nothing short of phenomenal, as three masters blended their sounds and styles with consummate ease. There was no mistaking the enjoyment each took in the others’ musicality, and their interactions were at once fiery and affectionate. The room was packed, and the response was overwhelming.

Before the show, Afropop’s Banning Eyre sat down with the artists for a chat. Here’s their conversation, and photos Eyre shot during the show.

Banning Eyre: Welcome to Afropop. Driss, I'm going to start with you because I have met many times with Ballaké and Rajery and I know something of their back stories. So please introduce yourself.

Driss El Maloumi: I'm a musician from Morocco. I play the oud. In 3MA and other projects also, I'm trying to present a different way of respecting the history and tradition of my instrument by exploring other universes and finding new ways to bring about musical ecstasy.

Nice. The oud is one of my favorite instruments.

Me too.

But I know there are many different oud traditions. Tell me which ones you grew up with that shaped the way you play now.

I am from Agadir. I was raised with both Berber and Arab culture. You know that Morocco is an intersection of cultures, especially sub-Saharan African, Arabo-Andulsian and Berber. It's a mix of all these things. So in our spontaneous music, you find all of these colors, all this richness. Me, I come from Berber tradition originally. So people ask me, "Why do you play this instrument? It is not a Berber instrument." And Arabs ask me, "Why don't you play a Berber instrument, since you are not Arab?”

I never really came up with an intellectual reason or made a conscious decision. I just listened to my internal voice. Ever since I was young, I have loved this instrument. I don't know why. It was the notes of this instrument that called me. I don't play in the classical way, even though I went to conservatory. I studied the classical tradition, the sama, the maqam, taksim… I love all of this, but I never felt pulled to make a career in these areas. I love exploiting these things, calling them forth in the music I compose, but I also want to do other things, to ask another question, to create another musical challenge. That's why I like playing with lots of different traditions in different international artists.

Tonight I find myself here with Ballaké and Rajery in 3MA, and we are continuing this voyage. There is no instrument that is specifically, 100 percent identified with a tradition. It is one’s spirit that creates these borders. If you remain open, and curious to explore the other, you find that the instrument will follow your desires as an artist.

Interesting. And I hear what you're saying about the richness of Moroccan music. It's a big world to draw upon. I want to hear the story of how this trio got started.

Rajery: O.K., 3MA began with an encounter in 2006 in Agadir at the Timitar Festival. That's where I met Driss, and we began to play together. Then we invited Driss through the French Institute to join our festival in Madagascar. That was a fantastic moment. And afterwards, we decided to continue. And that's when we called Ballaké.

The name 3MA came from the director of the French Institute in Madagascar, Bérénice Gulmann. She said, "Why don't you call yourselves 3MA?” And I said, “3MA? What's that?" Madagascar, Mali, Maroc!

Ballaké, tell me about the very first time you played these two guys, and what you remember about it.

Ballaké Sissoko: The first time was when we faced the challenge of tuning. And that was the most difficult thing. We spent weeks together in Madagascar. We got to know each other. We talked about things, we saw the possibilities of each instrument. But that first encounter was the most difficult. And that's what pushed me to create this kora I have now with sharps and flats. I can change to any tuning now.

Really? And how many strings?

Twenty-two. The thing is it used to be such a hassle to change tunings. There were many songs we couldn't play in concert because I couldn't retune quickly enough. But with the switches on this kora, I can change notes to flat and sharp quickly. So it was through this kora that I was really able to master this project.

I was about to ask you what the biggest challenge was in playing with this trio, but it sounds like you've answered the question. It was the problem of tuning.

Yes. Tuning. But once we solved that problem, it was on to other challenges. Me, I have a lot of experience, and with these guys it's the same thing. We show each other things. We know that music does not end with what we know already. And I think that goes for all of us.

Driss, what was the biggest challenge for you and playing with this group?

Driss El Maloumi: Well, the first thing was to fall into the charm each tradition, but at the same time to create a space that includes all three traditions. That's a big challenge. Because each of us comes from his own musical world. Each of us knows his own culture. But all three of us also have open spirits, and an ability to analyze our tradition and to try to move outside of it. We continue to do that because we believe in this openness of spirit. We believe in exchange. We believe in experience. And we believe that the best way to respect our tradition is to bring it outside and share it with other traditions.

I think that was the real challenge in 3MA. It can't be Malagasy music. It can't be Malian music. It can't be Moroccan music. It has to be all three at once. They have to blend together. That is a real challenge, and then, as Ballaké was explaining, there were the technical challenges, and even the manner of playing. I think that each of us has changed… no, not changed, but evolved our way of playing, gaining a new way to play one’s instrument through this experience with 3MA.

So in the end, I don't play the oud in an exactly traditional way. And it's the same for Ballaké and the same for Rajery too. We've had discussions about tonality, discussions about musical structures and discussions about rhythm. The first beat for you is not the same as the first beat for me. I think that all these challenges are really indispensable for any project that wants to find something new. This is not just an encounter to find moments of improvisation. On the contrary, we are looking for a new way to experience and blend our musical universes.

Rajery, is there anything you want to add about the challenges of creating the sound for this group?

Rajery: Yes, as Driss says, this is a meeting and a sharing of experiences among the three of us. To know and understand the music and culture of another person is a challenge. But before jumping into creation, you have to get to know the person, the human being. With 3MA, there were challenges. As Driss said, this is not Malagasy music, nor Malian, nor Moroccan. We had to really think about that, and what we were going to do together. So it was that profound reflection, and then the work. It hasn't been easy.

You said this started in Agadir in 2006, And then there was the time you spent together, and Madagascar. Was that all in the same year?

Rajery: The same year. After the festival in Agadir, I invited Driss to Madagascar. And then he came a second time with Ballaké to start the work. And then we did a concert at the French Institute. That was a big challenge. We were really under pressure.

Driss: Yes. The first time. It was the birth. The birth of a baby. There were many challenges. We were nervous. The stress. The way we looked at it in 2006 is not the way we look at it in 2020.

Of course. And that's my next question. We talked about the beginning. Let's talk about what it's like now over 13 years later. Talk about the evolution, the character of the group, the experience for you personally.

Driss: Well, we don't argue the same way. [Laughs] We've gained a certain maturity. For one thing, there's just the passage of years. When I look at Ballaké or I look at Rajery now, we understand each other much more quickly--musically and personally. We all have our faults, and we respect each other's faults. We try to improve and to show our best side, such as it is. Musically, the communication is deeper. Some things have changed. Some things have not changed. It's a beautiful adventure that we want to continue. We have really gotten inside each other's heads. We all have our own projects, but 3MA is a real jewel, and it has given each of us a new understanding. This is the only group to combine these instruments, the Arabic oud, the kora and the valiha of Madagascar.

After 13 years, we have learned a lot. We have listened back to the first concert in the first album to remind ourselves where we started. So there's been this continuity, but it's very difficult to describe. Each time we return to the stage after a period of separation, it's as if we just parted an hour ago. There's this feeling, this call from inside for the three of us. We are human. There are times of disagreement, and tension, and laughter too. But aside from all that, it takes just a phrase or a little rhythm, and Ballaké learns it, Rajery adds a variation, and then I take it, and we're off, like three old friends back together after a long separation.

That's beautiful. Ballaké, what has changed for you over these years?

Ballaké: Well after nearly 14 years, the group has gained a lot of experience, in terms of musical quality and feeling. We found the shortcuts. In the beginning, we took the long roads. We’re relaxed now, and for me that's very important. When we listen to each other is not the same thing anymore. You hear a note, and you can respond right away. That's very important. We've really mastered that. Our technique is the same, but there is more detail now than before.

So it's both a richer experience musically and also more fun.

Exactly.

Rajery, what's changed over the years for you?

Rajery: For me personally, it's my technique that has changed, and also our communication. We've taken care to refine our communication. There's a complicity between us now, and the public can feel it. They can see it. The way we look at each other. The way we interact. All this affects the finesse of the music, and even our solos. That too is very important.

So now you're coming to the end of another tour, as you say, after nearly 14 years. You must all like this project very much, right?

All: Yes, for sure.

Driss: We’re going finish this short American tour here tonight. But in the month of March, we will begin a European tour. I think we have eight or nine concerts there. A little bit here and there, France, Spain, Holland, England. And later on we have another tour in Australia. And I think next year we'll come back to the United States.

What about a new recording? You have two albums. Is there a plan for a third one?

Driss: Well, like any baby, it begins with discussion. And there have been some of those.

Do you have new compositions?

Ballaké [echoed by the others]: That is beginning…

How do you guys compose? Do people bring in ideas? Or do you improvise together?

Ballaké: We have every possibility. Something might be prepared, or maybe we’re on stage and someone plays something new and someone says, "Let's not lose that." And then we are always free to add new things later on.

Driss: That's right. This is a project that is open to every kind of creativity. It could be something classical or a theme that one develops in one's own way. It can happen on stage while we’re doing a sound check. Ballaké or Rajery starts playing a rhythm that I adore, so I take my instrument and start playing along. Then we quickly record it. Later on we develop it, and if it stays with us and continues to move us, then we keep and let it grow with us. If not, we let it go.

I’m going to let you go and get ready for the concert. Maybe you could tell me about a song you particularly like on the second album, Anarouz.

Driss: Let’s talk about “Awal.”

Rajery: O.K. Good.

Driss: The word awal is from the Berber language in Morocco.

Tamazight.

Driss: Exactly. And it means “the words,” and the song is a bridge between our three languages, Malagasy from Madagascar, Bambara from Mali, and Arab from Morocco. And so in addition to the instruments, each of us adds a few words in our own language, saying more or less the same thing. Were talking about our collaboration, and the continuity of the 3MA idea. So “Awal” is a song that we've kept since the birth of this project right up until our concert tonight.

I can't wait to hear it. Thank very much.

All: Thanks to you.