Abu Sadiya, released in April 2018 by Accords Croisés, might first come across as a simple album. This is a repetitive music, part jazz, part classical, with its roots in the stambeli genre that is indigenous to Tunisia. However, after a few listens, there is power in this music. Yacine Boularès plays the soprano saxophone and bass clarinet, Nasheet Waits plays drums and Vincent Ségal plays cello and percussion. They are all accomplished musicians: nobody takes center stage here or is seeking extra attention. There is a careful interplay and exchange among these musicians who listen to each other.

Yacine Boularès has contributed to jazz, classical, and also Afrobeat recordings with his band Ajoyo. Born of a French mother and Tunisian father, he grew up in France,. After playing in various musical genres, he has returned to his Tunisian roots. This is his best musical release to date. The stambeli is music that seeks to heal and put its listeners into trance. It has been described as “a music of peace,” by Salah el Ouergli, a well-known musician in this genre. It originates from sub-Saharan slaves of West Africa who were brought north. A stambeli performance is a rich interplay of sound, dance and song. Typically the music rises in intensity as night descends. The gumbri, a three-stringed lute, the shqashaq iron castanets, and the tabl drums are traditional instruments featured in this genre. Along with the classic rhythms, there is a modern dialogue here between the soprano sax, drums and cello.

This album is based on the story of Abu Sadiya. He is a figure of myth and intrigue in Tunisia. During the stambeli performance a dancer in costume plays his role. The album starts out gently with “Dar Shems,” as the slow rustle of brush on drums and the sax notes weave elegant circles around each other. The cello plays a steady, purposeful loop. Picture Abu Sadiya, a West African hunter alone, haunted by the disappearance of his daughter. He dances to enable his daughter to return to him. By the third track, “Bahriyya,” the steady, elongated sax notes entrance the listener. This is a mournful sound, reminiscent of the cyclical nature of Ravi Shankar or Phillip Glass's music: The repetition pulls you in.

Abu Sadiya's myth is pertinent to the present – to the tragedy of today's migrants. Yacine is quoted in the album notes as saying, “He [Abu Sadiya] incarnates the face of the migrant, the transformation of Africa. He resonates with who I am: a Franco-Tunisian who grew up in Paris yet stayed in touch with Tunisia. It's in New York that I resolved the fragmentation of this identity. The stambeli 6/8 and 12/8 rhythms are typical of the ancient Malian empire, and they went off to the north and Tunisia, but also to the West, the Caribbeans and jazz.”

On “Takhmira,” Nasheed Waits dances his brushes across the drums. The drumming is haunting. The sax now flies more freely, recalling John Coltrane.

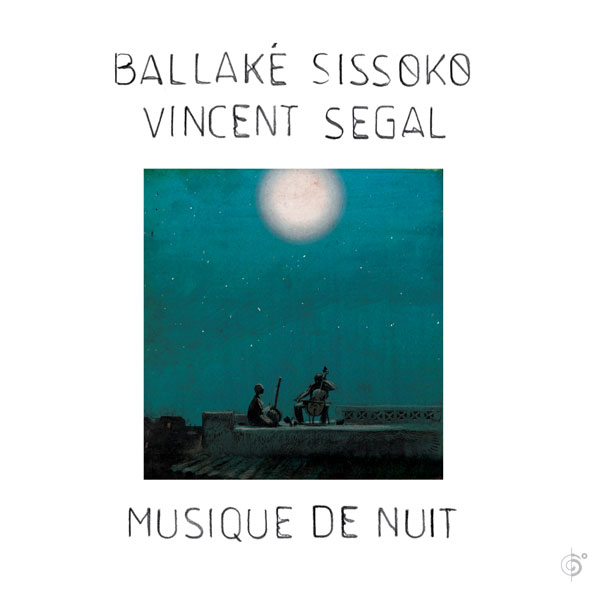

Although Yacine is the primary composer on this album, the music would not as be as moving without the other two stand-out musicians. Yacine trained at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique of Paris and later at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary music. He met Vincent Ségal during a recording that they both worked on for Placido Domingo. Ségal, a cellist, is noted for his unique musical collaborations with Elvis Costello and Ballalake Sisoko. Nasheet Waits studied music at Long Island University and has been active in jazz since early in his life.

Yacine described the musical interchange in a recent interview for Lincoln Center, “I think the quality of meditation that music puts you through develops empathy. Connection. A real connection, not just 'I’m going to talk to you because I need this from you.' I think as musicians, we're very lucky to have the time to meditate on ourselves and on other people's music and to develop this empathy.”

At the album's end, the pace picks up on “Nuba-Resilience.” Nasheet uses his drumsticks – before he had used only brushes. The music is forceful. By the finale, the album has cast its spell, and one feels compelled to wander again through the music as Abu Sadiya has, searching for his lost daughter.