In my world, I strive to be the character-narrator of my own life experience. As the world we knew falls apart, this is one of those moments when you are asked to overcome fear and hopelessness, step up to the plate, and take ownership of your narrative. It’s in precarious times of uncertainty that one has nothing more to lose by seeing things for what they are and speaking your truth.

The events of the past few years have seen global change precipitate at an Instagram pace, and my only fear is that the pace is so rapid that there isn’t enough time to process anything, and in turn, this silences our memory. I plan not to have others try to piece together experiences for me posthumously and would rather speak to the history of Afropop Worldwide in the moment, from an auto-ethnographic perspective, the collapse between biography and ethnography. By offering my insight into Afropop Worldwide's role before and during this liminal space where we are betwixt and between death but heading towards rebirth, I hope to illustrate a pattern of birth and death as the only constant in the cycle of life. The portrayal of Africa and its music has evolved in the context of changing political landscapes over the years, and Africa is now at a moment to take control of its narrative moving forward, with implications that might reverberate positively into its future. If it is left alone to chart its destiny. I will, however, index certain global recurring tropes, lived experiences, and political events that have shaped my perspective over time, and Afropop Worldwide has played a large role in that respect.

I first set foot in the modest home office of Sean Barlow at Afropop Worldwide in Washington, D.C., in the hot summer of 1989, as his first volunteer, motivated to stay close to the heartbeat of Africa - its music- and thirty-five years later, that is still the case. Afropop is that virtual space where anyone in the world can insert themselves when craving the Black experience and instantly feel at home. My story with Afropop began at its inception, and the social and political tropes of the late '80s seem to reverberate, seemingly bringing us back to the same place we were when we started. The capriciousness of American politics and administrations has been consistent, where foreign and national policy shifts every four or eight years, if we are lucky.

Today, we have crossed over into strange terrain where the checks and balances of so-called democracy have slipped away before our very eyes. One thing has been consistent for Africa and Africans: our position in the eyes of the West has consistently been precarious over the years, where the more things have changed, the more they have stayed the same. Our past experiences and resilience on the Continent and diaspora have prepared us to face many challenges without fear. The challenges simply had different names, but this time, everyone, not just Africans, is impacted. Africa has recently made bold moves, taken control of its narrative by demanding sovereignty over its mineral reserves, expelling European military bases, reestablishing regional cultural citizenship, and is looking to hold the future in its hands. One can say we have completed our Saturn return together, as I also celebrate my 60th year, with the majority of African states also celebrating their 60th year; we are undergoing a collective initiation.

Sean and I first met at his house party in Adams Morgan on a very hot summer night in 1989. The image above was captured at that exact moment. He began his fieldwork in 1985, recording live interviews in Africa using cassette tapes for documenting and sharing music he gathered on trips to Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Congo. A graduate of Wesleyan University, originally majoring in government back in 1975, his love for African music began after extracurricular studies learning African drumming and dance.

Banning Eyre entered the Afropop origin story until 1987 when he accompanied Sean on an early research trip to the two Congos, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Banning was also a Wesleyan grad, having majored in English. From that first trip on, the two would go on a lifelong journey discovering the endless genres of African music and sharing it with America and beyond. Research and recording trips took them to many parts of Africa, including Mali, Senegal and Zimbabwe. Thomas Mapfumo would be an anchor for their music documentary format that would last over thirty-seven years. Banning published Mapfumo's biography, Lion Songs, in 2015.

As CEO of World Music Production, Sean was able to translate his passion into a lifelong endeavor, premiering on NPR during a magical moment in its early history, characterized by experimentation, innovation, and inclusion. By 1988, his progressive idea of broadcasting African music from the continent into the national discourse at National Public Radio (NPR), through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), Afropop was launched as a one-hour, weekly radio program.

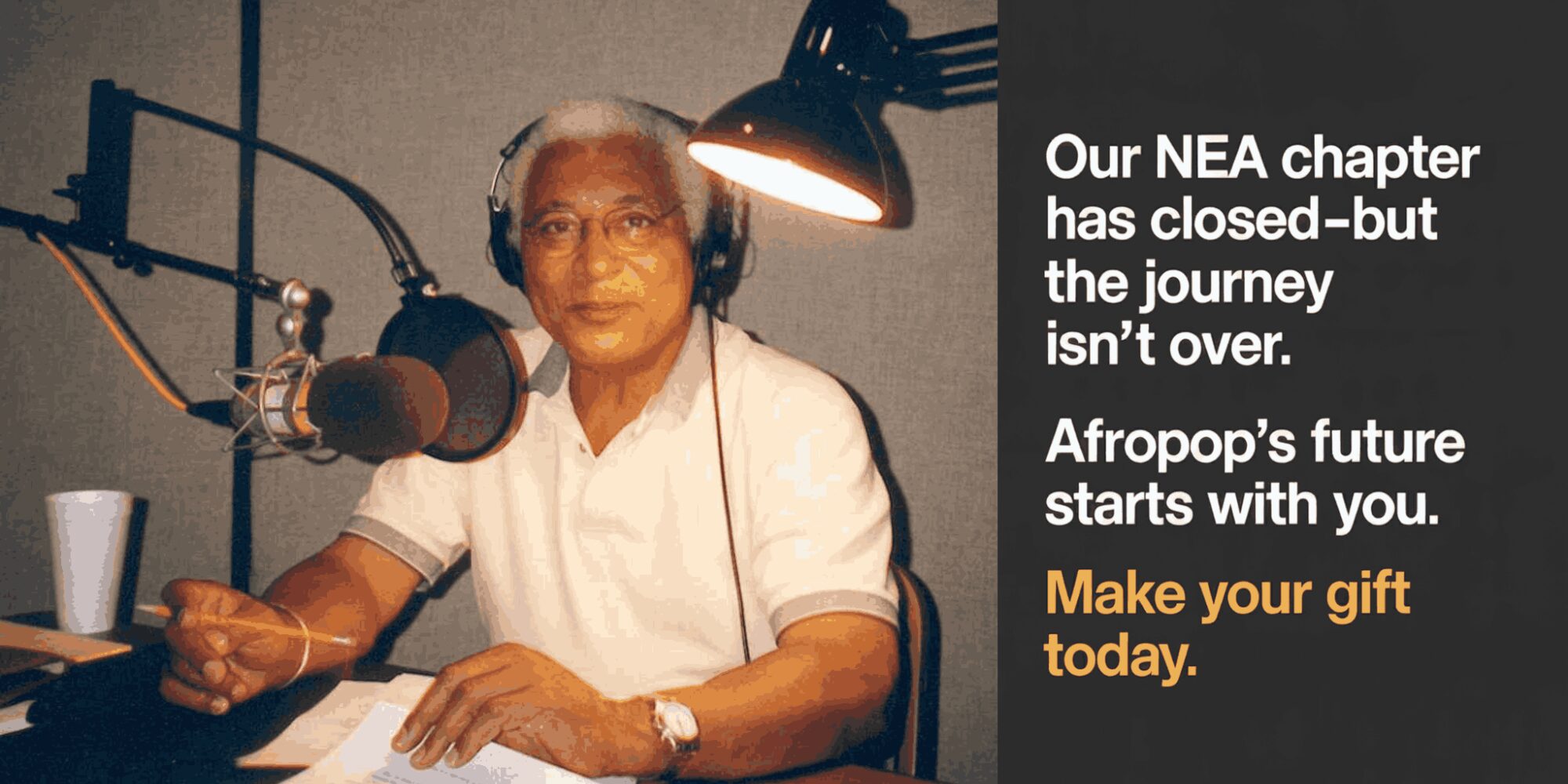

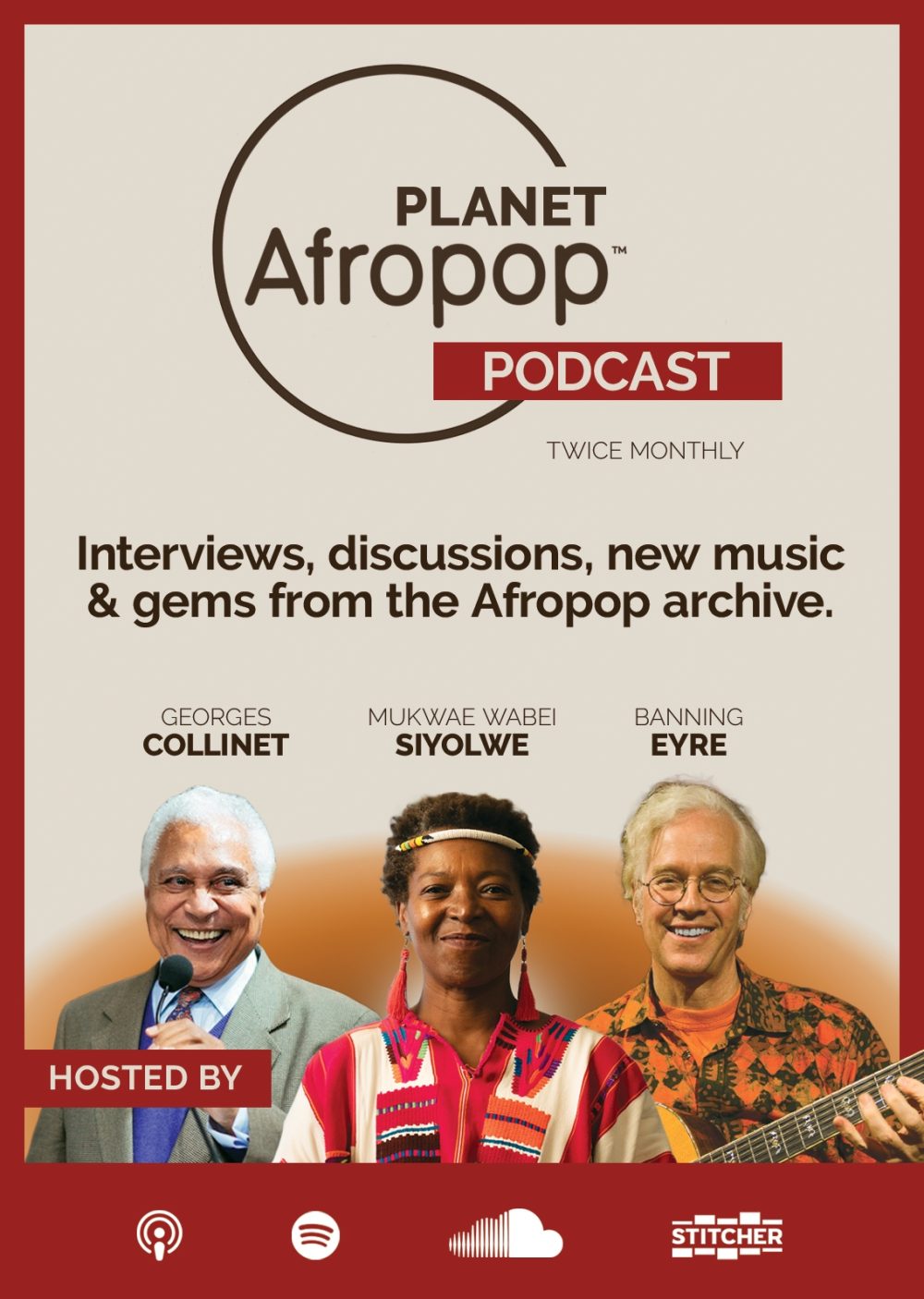

The show, dedicated to contemporary African music, came to life with the talents of legendary Cameroonian-French-American Voice of America journalist and broadcaster Georges Collinet as the host. Sean secured a competitive National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grant to produce a 52-part radio series on African contemporary music and expanded and became Afropop Worldwide in 1990, encompassing the African diaspora.

In the mid 80s, Afropop emerged within the context of negative coverage by mainstream media towards Africa. In 1989, we were still living in the shadow of the smear campaign towards Africa and Africans. The ongoing trope was that Africa and Africans were without a history, as famously proclaimed in the early 1960s by the eminent Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper who said, "there is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness", its past "the unedifying gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe". From 1969, he repeated this untruth, labeling the whole of the African continent as an abyss, leaving this image indelibly in our minds.

I inherently knew information was missing in my cultural memory. How was it possible that the history of Zambia began the year I was born 1964? Somehow, even the most intelligent Zambian was convinced of this falsehood as fact. The symbolism of this fake state seemed constructed and cherry-picked, with a linear disjointedness about our personal and national identities. I felt like a lion being told I was a domestic cat, and something in my bones knew there was much more, and indeed I found so much more in the years to come. Enough to reconstruct our national history from 1200 to today as the former Chairperson General of the Barotse National Freedom Alliance (BNFA).

This cultural dysphoria had manifested itself in my relationship with my singing voice. I felt like a fraud; imposter syndrome was my normal state of being, as I was pushed to sing opera and classical Western music by teachers from the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory when at home in Moscow. I never felt comfortable in my skin. The only remedy was to work myself backwards in time, where one day I believed I would be yoked back to my ancestral voice and find my place in the world. Afropop would play a role in this metamorphosis.

I had lived in DC as a seven-year-old when my father was a diplomat for the Zambian mission in the 1970s, when there was no real continental African presence in DC and Silver Spring was still a village. We were living through the height of the escalation of the Vietnam War, the break-in at the Watergate, apartheid in Namibia and South Africa, and many African territories believed they were ending their struggles against colonial systems of corporate capture. France, Britain, Belgium, Portugal, Germany, Spain, Italy and even Holland were reluctant to let go of their economic lifelines. Zimbabwe was in Chimurenga mode, wrestling itself from the British-sponsored Ian Smith regime. Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Tanzania, Zambia and Mozambique formed the Front Line States, actively opposing the apartheid regime in South Africa by providing support for the liberation movements in South Africa and Namibia. This federation risked their national security and sacrificed resources where their collective support was the difference needed on the ground to finally turn things around, along with sanctions.

The year 1989 was a hot year to say the least, with the March geomagnetic storm, which occurred as part of severe to extreme solar storms affecting climate, power and politics. The proposal document for the World Wide Web was submitted, Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing were raging, and the liberation of South Africa and Namibia were imminent. Southern Africa was dependent on efforts from sympathizers in Washington, DC, Cairo, and Moscow, which were the hubs for lobbyists, refugees, students, artists, and intellectuals. My family lived in all three territories between 1972 and the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Many of the liberation movements had intimate relationships with artists against apartheid who passed through my nomadic homes, like Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, Dorothy Masuka, Letta Mbulu and many more, who were huge influences in my life. Nelson Mandela was classified as a terrorist at this time.

As an African, surrounded by exiled African artists, their late-night conversations were my gateway to African culture in exile. Their histories, languages and music were my escape, but at the age of 9, this lifeline was cut off. Due to the constant moving back and forth from one mission to the next, being sent to an English all-girls boarding school in Sussex, I spent much of my youth alone and isolated. We were all sent to various exclusive boarding schools around the world in some sort of experiment by my father, a former mathematics teacher and career diplomat, who had been convinced we would all turn out alright if we had a “superior” Western education, albeit without a single class in African history or philosophy for ten years. Clear evidence that the contradictions of colonialism wreak havoc on the natives of colonized spaces globally.

In our respective exile across the globe, my siblings and I all had to confront the world alone, where we were all fed a famished version of Africa and where everything about Africa that I grew up believing was a fiction concocted to keep me asleep as corporations stole the resources back home from right under my feet.

The negative tropes persisted into my youth, pushed forward and exacerbated into the 70s by the wars and famine in Ethiopia, where images of emaciated African babies were shown daily on television screens, much like the images we see today of Gaza. By the 80s, Live Aid and Feed the World, and the, in my view, patronizing and insulting tune that went platinum, “Do They Know It's Christmas Time at All,” were being played 24/7 across the world.

In reality, at the same time, a rebirth of African music on the Continent in Mali, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal, Congo DRC in particular, was well underway. But Afropop Worldwide was the only national broadcast media platform putting a face to those luminary African musicians emerging during that renaissance, who included Tshala Muana, Ali Farka Toure, King Sunny Ade, Ebo Taylor, and Fela Kuti, Lucky Dube, Nahawa Dumbia, Brenda Fassie, Cheb Khaled, and many more who were given little to no other coverage for their brilliance. By the mid-80s, the other pandemic came around, the associations of sexually transmitted HIV/AIDS and monkeys, all but projected the collective African population to extinction, and families and economies on the Continent were decimated.

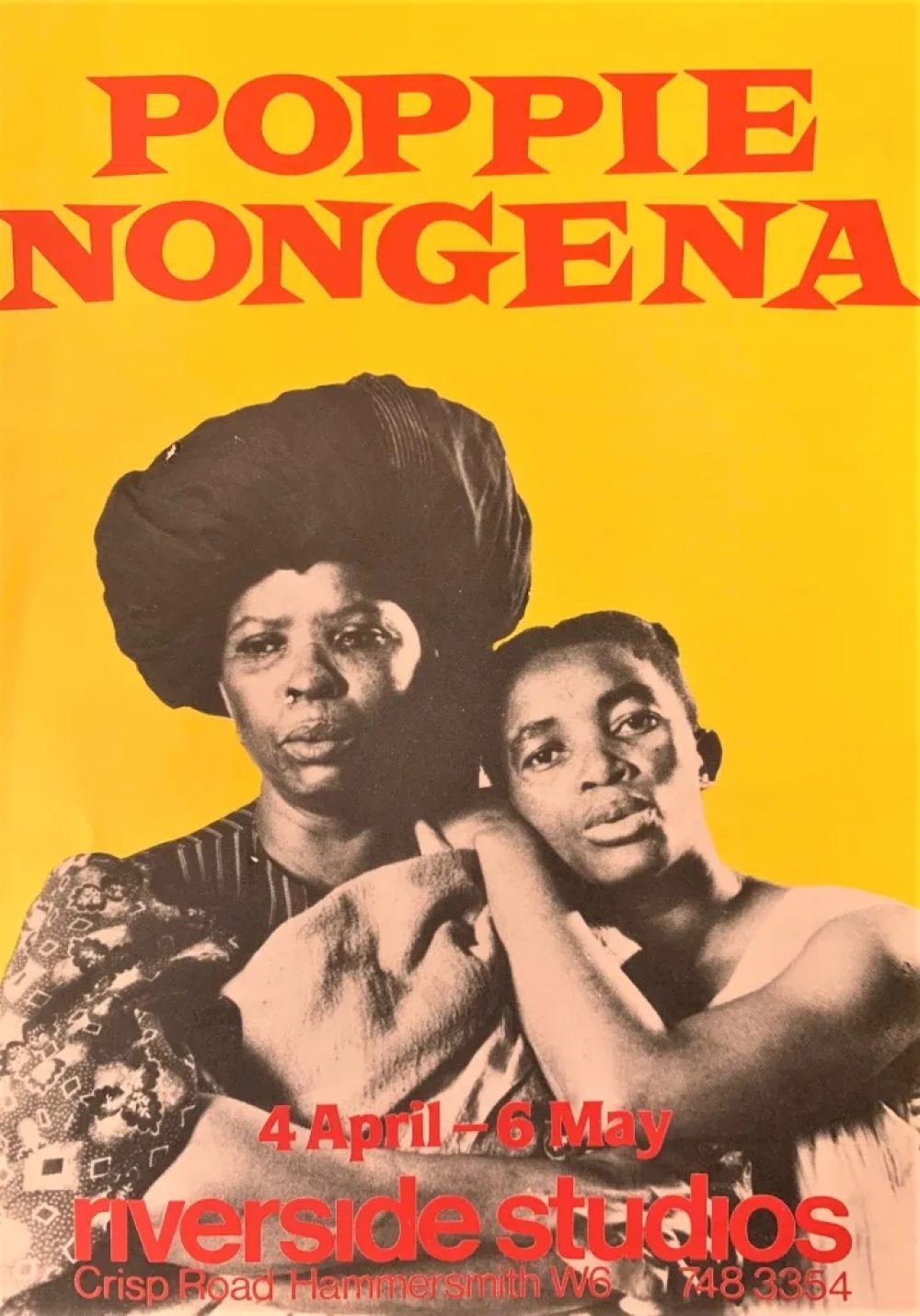

Fortune had followed me, in the form of South African singer, songwriter, and composer in exile, Sophie Thoko Mgcina, an original cast member of the first South African musical by Todd Matshikiza to make it to the West End, King Kong (1959). Sophie was my informal vocal teacher in 1985 while I was at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London. At this time, I had not one Black teacher at the Guildhall, but Sophie was an adult student in exile also studying there. We spent lots of time together as she was starring and was the musical director of Poppie Nongena, a musical play that was opening in London. Sophie got me a job as an usher. I was finally close to my ancestral source. Every performance would leave my heart exploding, watching in the wings as Thuli, who would later sing the title track of Cry Freedom and play Rafiki in The Lion King, opened the doors for scores of South African artists to the production.

By the time my final year at the Guildhall came round, Leonard Bernstein cast me as the Jazz Singer in Mass in a retrospective of his work at the Barbican Center. This final year production would catch the eye of legendary casting director Susie Figgis, who introduced me to Oscar-winning director of the motion picture Gandhi, Lord Richard Attenborough, who created a supporting role for me without a screen test in his new film about Steve Biko, Cry Freedom. Like a bolt of lightning, before I graduated from the Guildhall in June 1986, I first heard the song "Nelson Mandela" by Youssou N'Dour in the back of a limousine on our way to Heathrow airport with journalist, writer, and actor John Matshikiza. I was going to play Tenjy Mtintso, and we were heading to principal photography to co-star with Denzel Washington in Cry Freedom (Universal). I became part of the struggle in a real sense as we filmed in Zimbabwe during the height of armed insurgency, which continued unabated, and we had several bomb threats on the set in the process.

By the 1990s, the campaign to subjugate Southern Africa was in its violent death throes with a military escalation by the racist nationalist government of South Africa called “Total Onslaught" (Totale Aanranding). This campaign marked the closing years of the armed struggle to liberate Black South Africans and Namibians from apartheid, which had begun in 1948. In 1990, Resolution 435 was passed at the UN, and there was finally a pathway to independence in Namibia, and change was finally in sight for South Africa. I was on my way to be the first Black lecturer to integrate the Theatre department at the University of Namibia, but African family members would disapprove, thinking I was mad for wanting to go back to Africa, a virtual death sentence as they saw it.

It was at this moment that the mission of Afropop expanded in 1990, and the program was re-named Afropop Worldwide, encompassing the African diaspora, and covering Francophone, Lusophone, and Spanish-speaking territories and ex-colonies around the world, and including Latino communities in New York. Black popular culture was taking off in new ways in the United States, the United Kingdom and South Africa, respectively. These three territories shared colonial history and British Common Laws as they related to censorship, race, class and gender relations in arts and entertainment. Their narratives were still enmeshed, and southern African artists were telling musical stories influenced by the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. The U.K. census's first inclusion of the question on race and ethnicity, and Ronald Reagan's targeting of policing in the ghettos of America during the War on Drugs also came that year. However, our U.S. media was way behind France and the UK in the 80s in terms of African music history and African history in general.

By the '90s, apartheid was reaching its demise, and new genres of contemporary music in the Black world were erupting with pride and included mbaqanga, the jazz-infused dance genre out of the Johannesburg townships, to Chuck Brown-inspired Gogo in South-East Washington D.C., Salt N Pepa hip-hop from New York, and funk, soul, jazz and hip-hop infused Acid Jazz of Soul II Soul in London. Music by Joe Mafela - Shebeleza (OKongo Mame), musicals and films like Poppie Nongena, Sarafina, and movies like Cry Freedom, A Dry White Season, and Mandela, were all released simultaneously across these territories, culminating in a final push through artists against apartheid, coupled with sanctions that finally toppled apartheid.

The Afropop experience had made me comfortable around displaced Ethiopians, Somalians, Congolese, Sudanese, Guatemalans, Salvadorans and even Nigerians. I returned to visit old friends in Washington, D.C., and gravitated to exiles all trying to live our lives as though we were back in our imagined homelands. I felt at home in Mount Pleasant and Adams Morgan, the cultural hotbeds of the African diaspora in DC, with 18th Street and Columbia Road as the nexus. I brought to my diasporan community a sense that artistically we were finally visible as Africans from Africa as equals to the West, seen on the big screen, and Afropop Worldwide´s impact contributed to a shift in the perception of African people and culture in America, as well as providing legitimacy and a sense of belonging.

The Washington DC of the early '90s between 18th St. and Columbia Road became Little Ethiopia, because of the larger numbers of Ethiopians, where seeing Aster Aweke eating at the Red Sea and many other restaurants became the home ground for intellectuals and artists in exile, as well as aid workers on hiatus from the field. This was a cultural district with an ecosystem supporting displaced Africans, where we would meet on the weekends and dance through the night at the Kilimanjaro club. I arrived at Afropop Worldwide at the convergence of all these events and the dawn of the Internet. The beginning of a spatial turn and a new chapter in the history of information exchange with the introduction of the first browser, Netscape. Sean was three years into his NEA-funded 52-part radio series on National Public Radio, now called Afropop Worldwide.

By 1997, I had returned from Namibia and was married to an African American and back in Baltimore and DC at film school when Afropop.org, a companion website, was launched, providing wider access to the program's content. The "Hip Deep” series, produced by Ned Sublette, Banning Eyre and Sean Barlow, launched in 2002 with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Hip Deep became a sub-series of the radio program, offering music documentaries that explore history and culture through interviews with historians and ethnomusicologists, as well as artists, also extended web features, and, eventually, podcasts. Afropop Worldwide would go into history as being one of the first music broadcast corporations to make its home on the Netscape web browser and the World Wide Web, singularly dedicated to playing African music. Suddenly, this opened up Afropop from being a niche program on National Public Radio (NPR) and affiliate stations to being able to legitimize African music and culture within the larger music industry, with reach beyond mainstream media.

On a personal note, my career and life would now be taken over by children, more professional acting, terminal graduate degrees, embracing my American identity, learning the musical songbooks of negro spirituals, and playing African-American heroines like Ida. B. Wells in new plays and opera. In 2015, Afropop Worldwide was awarded an institutional Peabody Award for its pioneering role in the "world music" movement. By then, Georges Collinet had become a household name in African music radio and film circles. So in 2022, I returned to Afropop after a hiatus of over thirty years. During this period, I was blessed to participate in the explosion of appreciation of African contemporary music and culture, whose energy not only motivated me to return to Afropop but inspired the whole world. There is no doubt that during COVID and the global lockdown, the global family had an opportunity to be still and listen to African music. Historic Dance challenges like "Jerusalema" from Master KG featuring Nomcebo saved our souls together, as well as love ballads from Rema, who led the Afropbeats pack, making him the first African teen idol of the decade.

My work led to collaborations with new partners, the use of new media tools for annual fundraising, revitalizing the board with new members, and enacting new operations protocols--all giving back to Afropop Worldwide for the gifts all the artists gave to me. Together with Senior Producer Banning Eyre, we conceived a new podcast with a mission to reach future, younger audiences: Planet Afropop, co-hosted by Georges Collinet, Banning and me.

In closing, challenges continue at Afropop Worldwide as we put attention into continuing to curate artists and expose them through our journalism, appearances, and collaborations with festivals and showcases we produce. The capacity to fund the organization after losing our founding grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), this summer is an ongoing challenge that will need more funding, viewer support and innovation in our output.

The challenges are not much different from the hot summer of 1989 when I started. Instead of a Cold War, we are in a trade war, and ground wars are raging in Europe and the Middle East. We are beyond a Cold War with China and Russia, which are ready to retaliate against all threats. At this point, 22 African countries are on a growing list for the U.S. travel ban, as we speak, and this impacts their ability to perform on U.S. territory. The many arbitrary decisions to dismantle soft power and diplomacy in Africa and beyond. They include unabated destruction of the U.S. international trade and tourism with draconian immigration policies, destabilizing science research and healthcare, social insecurity, disregard for law and order, DEI shredded, arts and education desecrated. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) have just been killed off, and the very constitution that has held this country together for over two hundred years is a thing of the past.

Every cloud has a silver lining, and the next generation will not be in exile, that is for sure. The option left to many is to remain or return to Africa. Afropop has created an archive spanning from 1985 to 2025 and planted seeds for the next generation on the Continent, training young producers to carry the story forward and shape their destiny.

Related Audio Programs