So, is it five notes? Two notes? How long before you know “Africa Mokili Mobimba” is playing? This year, let’s celebrate the 60th anniversary of this classic African song created by the band African Jazz.

It was 1961, in the very early days of Congolese rumba, when Luambo Makiadi (Francois) “Franco” and Kabasele Tshamala (Joseph) “Le Grand Kallé” were giving birth to Congolese rumba, which brought together foreign musical influences and Western instruments with indigenous musical rhythms. Some consider African Jazz to be the most important Congolese band, and Kallé the “Father of Congolese Music.”

Kallé had formed African Jazz in 1953, during Belgium colonial rule, and it would be the breeding ground of so many future greats, including guitarist Kasanda wa Mikalayi (Nicolas) “Docteur Nico,” Tabu Ley (Pascal) “Rochereau,” and Emmanuel N'Djoké “Manu” Dibango. African Jazz was one of the first groups to introduce African popular music into the European market. Let’s chronicle the history of the African Jazz sound by following the iterations of its seminal classic song, “Africa Mokili Mobimba.”

The Song

The song’s original title was “African Jazz Mokili Mobimba,” which translates as “African Jazz all over the world.” It was written by Docteur Nico’s older brother, Mwamba Mongala (Charles) “Déchaud,” the band’s rhythm guitarist. The anti-diasporic lyrics caution against excessive travel abroad -- foreseeing future tensions that developed when Congolese musicians spent more and more time in Paris and Brussels, rather than in Kinshasa. It was also one of the first African recordings to make use of 45 rpm records, which permitted longer songs than 78s did.

Ben Richmond, in this blog, has astutely observed the song’s pan-Africanism. Unlike in Asia, South America, or any other continents, there is a longstanding folk tradition in Africa of roll-calling the names of African cities and nations, and we hear this in the signature chorus: “Kinshasa, Matadi, Boma, Mayombe, Mayi, Mongala, Equateur, Kivu, Maniema, Kisangani, Brazza, Pointe Noire, Cameroon, Ghana, Guinee, Mali, America"…

Other artists followed in this tradition, for example Salif Keita in “Africa:” “La Guinee, Le Gabon, Senegal, Yaounde.” Pepe Kallé reached across the pond in “Zouké Zouké:” “Guadeloupe, Martinique, La Guyane, Haiti, Dominique.” Even Tiken Jah Fakoly took aim at corrupt postcolonial governments in “Francafrique:”

Ils ont brûlé le Congo

Enflammé l'Angola

Ils ont ruiné le Gabon

Ils ont brûlé Kinshasa

Fans called Docteur Nico “Dieu de la guitare” (God of the Guitar). Playing lead, with his brother Déchaud on rhythm guitar, in various versions of this song, they added a third guitar between theirs. That innovation came to be known as the mi-solo. Recently, a guitarist very familiar with this unpacked Docteur Nico’s innovation:

Black-owned Business

One reason Kallé has been called the Father of Congolese music is because he was the first African musician to create his own record label, Surboum African Jazz. He was responsible for striking deals with European record labels to ensure high quality recordings of his band's music for the Francophone market. Even some records from his key rival, Franco, came out on Kallé’s label.

Kallé was not the only Congolese musician to be involved in the music business. Tabu Ley opened up a club in Kinshasa, Type K, and even delved into coffee exporting. Dictator Mobutu Sese Seko could see the popularity of these young stars and began handing out goodies to those he thought could be useful to him, especially after he nationalized much of European-owned industry.

(Mobutu was fervently anti-colonialist and launched a campaign for authenticité, renaming cities and changing the country’s name to the Republic of Zaire. He ordered the people to change their European names to African ones. At each musician’s first mention, this essay puts European names in parentheses, stage names in quotes, and leaves Zairian names alone.)

Franco cashed in the most from Mobutu-approved business opportunities. Belgian Fonior was to exit from its record-pressing operation, MAZIDIS. This plum went to Franco, as did another record-presser, SOPHINZA. Censorship was heavy in Mobutu’s Zaire. Franco somehow managed to get his most obscene songs onto shelves despite this, by giving gifts to the censorship commission or by pressing them in Belgium and getting cassette copies sold in Zaire.

The censorship commission was just one example of Zairian bureaucratic overreach. Mobutu allowed Kallé, and after that Tabu Ley, to run the agency that collected fees for musicians, SONECA, meaning they had the power to affect every Congolese musician’s livelihood. Franco was put in charge the musicians’ union UMUZA. At one point, he had approval rights over his fellow musicians’ travel; he could nix their tours if he wanted. Franco’s successor at UMUZA, Madiata Madia (Gerard), even teamed up with some African Jazz bandmembers to try his hand at “Africa Mokili Mobimba” (Please excuse the watermark; it only lasts 60 secs.):

Endless Breakups

Kallé was bandleader, so he disbursed money from bookings. Now he was running Surboum, controlling all royalty payments. After “Africa Mokili Mobimba” became a hit, Kallé was seen driving around Kinshasa in a white Cadillac. African Jazz in its original configuration did not last long after that. Like so many Congolese bands torn apart by money issues and other internal dissensions, the defections began. In the Congolese music scene, years of breakups, backstabbing and poaching were to follow, resulting in some volatile years of conflict, especially between Franco and Tabu Ley later on.

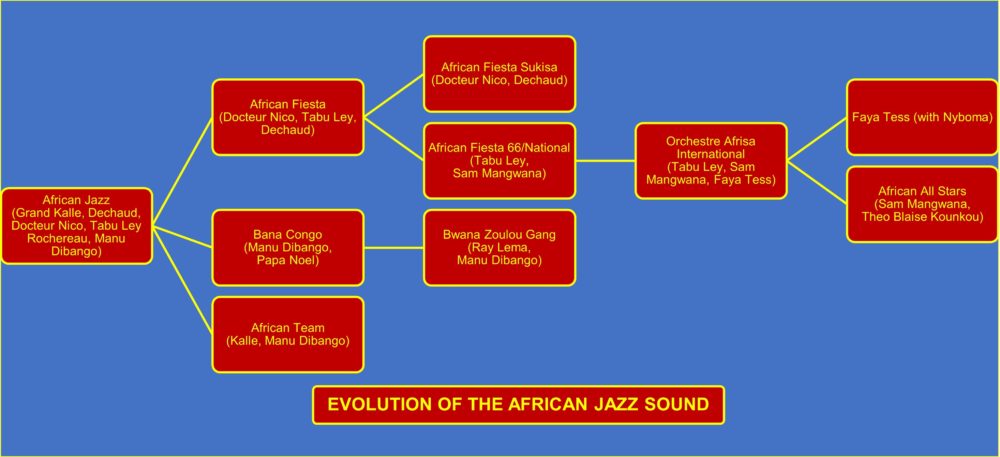

First Déchaud, author of “Africa Mokili Mobimba,” his brother Docteur Nico, lead guitarist, and Tabu Ley left to form Africa Fiesta. But Tabu Ley was unhappy with that arrangement and splintered off African Fiesta 66, where he brought in brilliant young singer “Sam” Mangwana Mayimona. Déchaud and Docteur Nico named their vestigial band African Fiesta Sukisa.

Members of African Fiesta 66 may have been surprised they made it to 1967, so they changed their name to African Fiesta National. It was not long before Tabu Ley and Mangwana formed a new band, Orchestre Afrisa International. Here Tabu Ley and Mangwana are doing “Africa Mokili Mobimba” in full sapeur outfits:

Tabu Ley found a young singer Mbilia “Bel” Mboyo, who soon became a major African diva. By this time, Afrisa was big and successful enough for Tabu Ley to bring on an understudy, Kishila Ngoyi “Faya Tess.” Rumors circulated, and were denied, of hostility between the diva and her understudy. Eventually, both women left Afrisa to pursue solo careers, and Faya Tess later teamed up with Nyboma Mwan Dido to record “Africa Mokili Mobimba.” Here’s a more recent clip of her lip-syncing the song for some old-timers dancing at a small club:

Mangwana parted ways with Tabu Ley as well, teaming up with Theo Blaise Kounkou to form African All-Stars, later launching a solo career, and recorded his own version:

After the painful exits of Docteur Nico, Déchaud, and Tabu Ley, Kallé had lured Nedule Montswet (Antoine) “Papa Noel” from the top Brazzaville band, Bantous de la Capitale. Kallé got together with Manu Dibango for a new band, African Team. Further down the road, Papa Noel had his own band, Bana Congo, and Dibango was part of it.

Papa Noel made an important contribution to the African Jazz sound by shifting into reverse towards Congolese rumba’s Latin influence. In the 19th century, Cuban son had derived from the music of African slaves -- call-and-response, percussion and thumb piano. In the 1930s, radio listeners in the Congo definitely heard something they could relate to in contemporary son imported from Cuba (Trio Matamoros, Sexteto Habanero, and Havana Casino Orchestra). Kallé was the first musician to mix Cuban rhythm with traditional African beats, and many of African Jazz’s early recordings are in Spanish. Sometimes Congolese musicians sang in Spanish without even knowing the meanings of the words. So, when Papa Noel and Manu Dibango recorded “Africa Mokili Mobimba,” they pushed the song back to Congolese rumba’s Cuban roots:

It’s unlikely the rapid creation, dissolution, and recreation of Congolese bands is matched in too many other countries. But it’s all good. A useful contemporary term we have is “creative destruction.” The chart provided here is just the big picture, missing innumerable jam sessions, one-night collaborations between musicians -- and obviously any time spent over with Franco.

The African Jazz sound is a seminal creation in the history of Congolese music. It embodies the transition from Cuban son-derived early Congolese rumba through to soukous. This is not meant to diminish the towering contribution of Franco. The sebene is a fundamental part of nearly all Congolese popular music since the 1950s, however Franco takes a different path by extending it luxuriantly. From these explorations by Franco, it could be said came the genius work of Zaïko Langa Langa, and then eventually an evolution into the ndombolo sounds of Agbepa Mumba “Koffi Olomide,” Mpiana Mukulumpa “J.P.,” and others.

Passing of the Father

There are at least 50 renditions of “Africa Mokili Mobimba” out there, including by well-known Congolese musicians like Tshala Muana, Ray Lema, and Ricardo Lemvo, plus most recently, as noted by Ben Richmond in this blog, by Playing for Change. Expect more.

And how much money did the author of “Africa Mokili Mobimba,” Déchaud, make from this enduring classic? Not much, it seems. Originally, Kallé had bought the rights to music members of African Jazz composed. Later, regarding money owed to Déchaud, Tabu Ley said “Sonodisc [which had acquired the rights] knows that Déchaud, until his death …will be powerless, or to go to court …He’s owed things.”

The revered Kallé died at age 52 in 1983, the first to depart among the royalty of Congolese music. Before a funeral cortege wound its way through grieving crowds, his body lay in state, and 500,000 people filed past it.

The author of this essay is deeply indebted (i.e. giant neon footnote) to Gary Stewart, whose opus “Rumba on the River” should be required reading for anyone interested in African music – or any music, for that matter.

dj.henri is a New York City DJ who has performed at the Apollo Theater, B.B. King’s, Symphony Space, and elsewhere. He is also the creator of radioafricaonline.com.